A basic guide to the greatest Matsukata Collection in the world—The unusual life of the businessman who produced the National Museum of Western Art

Harada Maha, Author

©MORI Eiki (森栄喜)

Ueno Park is now a major cultural base. I think you already know that its center is the modern National Museum of Western Art (NMWA) designed by Le Corbusier.

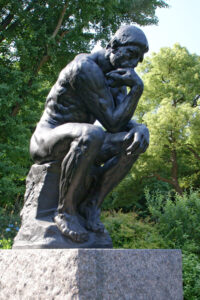

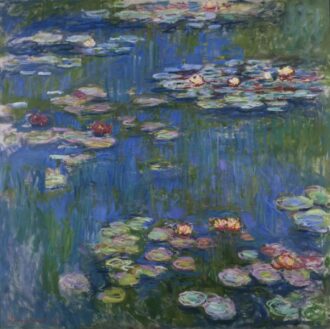

Many people have enjoyed seeing Water Lilies by Claude Monet at the NMWA. Great paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Paul Gauguin are on display throughout the museum, and a collection of Rodin’s sculptures, such as The Thinker and The Gates of Hell, are precious works from a global perspective.

However, I assume that few people today are aware that these artworks used to be a collection owned by a Japanese businessman, and that the NMWA was originally built to house that man’s collection in response to a request from the French government. The name of this businessman is Matsukata Kojiro. He was born as the third son of Matsukata Masayoshi, Prime Minister in the Meiji period, was the first president of Kawasaki Shipbuilding Company (currently Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd.), and also assumed the presidencies of the Kobe Shimbun newspaper and Kokusai Kisen line during the same period. He traveled to Europe many times, purchased and collected a large number of artworks in Paris and London in the 1910s to 1920s as well as working in the shipping industry, and dreamed of building an art museum in Japan. However, Masukata’s dream was shattered by a financial crisis. A collection of more than 1,000 works in Japan was sold by its creditor, and the works were scattered and lost. About 900 works that remained in London were burned in a warehouse fire. About 400 works stored in Paris were requisitioned by the French government as enemy property at the end of World War II. In the end, Matsukata died at the age of 84 in 1950 without seeing his own collection again.

National Museum of Western Art in Ueno, Tokyo and Rodin’s The Thinker and The Gates of Hell

Photos: 663highland/Creative Commons

Yoshida Shigeru rose up

Matsukata Kojiro (1866-1950), Public domain

The then Prime Minister, Yoshida Shigeru, learned that Matsukata’s collection had remained in France after the war and worked hard to get it back. Yoshida and Matsukata had been close friends since before the war.

On September 8, 1951, the San Francisco Peace Treaty was signed. On the day after the conference, Yoshida visited French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman at his hotel, despite a schedule that had everything planned to the minute, to have a 20-minute face-to-face meeting, and asked him in person, “Could you please get Matsukata’s collection back?” Schuman said, “All right” and added, “I may not be able to get all of the works back to you. I am concerned that the works will be scattered and lost, so I would appreciate it if you would construct a special art museum.”

This is how the negotiations between the Japanese and French governments started. Every effort Yoshida made for the “avenging battle” for his old friend resulted in the return of nearly 400 works and the building of the NMWA.

Yoshida Shigeru

Photo: National Diet Library, Japan

Robert Schuman

Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-19000-2453/CC-BY-SA 3.0, Creative Commons

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the NMWA, which opened in 1959. “Upon the 60th Anniversary of the NMWA—THE MATSUKATA COLLECTION: A One-Hundred-Year Odyssey” is being held from June 11 to September 23 in celebration of the anniversary. If you go a little further and visit the nearby Tokyo National Museum, you can also see part of a collection of 8,000 ukiyo-e works that Matsukata purchased in bulk in Paris and was able to bring back to Japan in good condition. What type of person was Matsukata Kojiro, who put a huge sum of money into the collection of artworks and drove Yoshida Shigeru even after his death?

For this memorial year, the NMWA conducted quite a large-scale investigation and traced the footsteps of the Matsukata Collection that had been scattered both inside and outside the country. I have also felt attracted to the life of Matsukata Kojiro in the last few years, which has resulted in my checking materials, interviewing people related to him, visiting places in France associated with him and writing a novel titled Utsukushiki orokamonotachi no tableau (Beautiful tableaus of foolishly honest men).

Why are there many art museums like this in Japan now? Why do Japanese people love art and art museums so much, and why do they feel a sense of connection toward Western paintings, including Impressionist paintings?

If they are asked these questions anew, many people probably wonder why. I think that you will be able to find the clue to answering these questions from getting to know Matsukata Kojiro’s unusual life and the checkered history of his art collection.

“I know nothing about paintings”

Matsukata Kojiro was born in Kagoshima Prefecture in 1866. His father was Matsukata Mayoshi, a prominent statesman of the Meiji period who held important positions, such as Chief of the Ministry of Finance and Prime Minister. Kojiro was a young scion of a wealthy family after the Meiji Restoration. Under these ideal circumstances, he was brought up to be a third son with a unique character who was distinctively different from his first brother, who later became president of the Fifteenth Bank, and his second brother, who later became a diplomat. There is a story that when he was a child, he leapt from a roof to surprise a friend during a sword fight and tore his Achilles tendon. This serious injury forced Matsukata to carry a stick with him at all times in his later years.

Matsukata was called to go to Tokyo by his father at the age of nine. Matsukata was such a good student that he went on from Kyoryu gakko (currently Kaisei Academy) to Daigaku Yobimon (University Preparatory School) (the old First High School later). But he continued to fail to move up to the next grade because of poor grades. He boycotted the graduation ceremony together with his friends and acted as a bankara (students with a rough or rude appearance) student in his youth. He was finally expelled from school and successfully persuaded his father to allow him to go to Rutgers University in the United States. He then went on to Yale University and earned a doctorate in civil law.

Kawasaki Shozo, who was also from Kagoshima and founded Kawasaki Shipbuilding Company, paid Matsukata’s school fees. Kawasaki lost his three sons early in life, with his third son, Shinjiro, dying while studying in New York. His body was carried to a graveyard near Rutgers University, and Matsukata was one of the students who carried his casket. Kawasaki, who had confidence in Kojiro’s character, said to his father, Matsukata Masayoshi, “I can’t think of anyone else but Kojiro as a candidate for the presidency of Kawasaki Shipbuilding Company.”

Matsukata, who assumed the presidency of Kawasaki Shipbuilding Company at the age of 30, succeeded in building a dry dock (graving dock), a long-cherished wish of the company. He subsequently accepted an order for a ship to transport military supplies for the Russo–Japanese War and an order for a naval submarine, and made remarkable achievements riding on the wave of the munitions boom.

World War I, which broke out in 1914, significantly changed the destiny of Kawasaki Shipbuilding Company and eventually that of Matsukata Kojiro himself. He thought, “The world will face a shortage of ships in the near future. All we have to do is to build ships before that.”

Matsukata came up with the idea of stock boats when he heard about the outbreak of the war. It takes a huge amount of money and time to build a ship, and they are usually built after an order is received. But Matsukata had the opposite idea: build ships first, keep a large stock of them, wait for a flood of orders and sell the ships at high prices. Matsukata’s strategy proved to be correct. A flood of orders for ships poured into Kawasaki Shipbuilding Company. Matsukata went to the United Kingdom to sell ships.

On his business trip to London in 1916, Matsukata purchased artworks for the first time.

Matsukata was on his way to success as a businessman, boosting ship sales several times with his bold idea. What made him suddenly decide to buy and collect artworks, in which he had not previously had any interest?

It is said that what triggered his interest in artworks was that he found a painting of a dockyard by Frank Brangwyn at a gallery in London that he happened to enter in order to pass the time. Matsukata, the president of a dockyard, felt a sense of connection with a painting of something familiar.

Even after Matsukata became known as an art collector, he declared, “I know nothing about paintings.” But he felt a connection with the painting of the dockyard, thinking, “There is something good about this.” A sense of connection is very important as an introduction to art.

This is what I imagine as a writer. I speculate that Matsukata, who first had an interest in a painting through a sense of connection, later developed a cause of creating an art museum.

In Japan, artists of Western paintings such as Kuroda Seiki began to work actively in the late Meiji period. In addition, intellectuals of the Shirakaba-ha (literally “White Birch Society”) actively introduced Impressionist painters, which helped boost Japanese interest in Western paintings in the Taisho period (1912–26). But there were still no art museums of Western paintings in Japan. Most Japanese had seen Western paintings only in the form of poor magazine illustrations.

Matsukata said the following: “Painters in poor countries cannot come into direct contact with Western paintings unless they push themselves to go to Paris. That is why I buy a lot of paintings and sculptures so that people can enjoy seeing them back in Japan.”

While staying in London, Matsukata formed a friendship with the painter Brangwyn and started thinking in earnest about building an art museum.

Matsukata, who asked Brangwyn to design an art museum and returned to Japan in 1918, convened Kuroda Seiki, a friend of his, and other associated members and consulted them about his plan for an art museum. He named it the Kyoraku Art Museum and discussed the idea of building it on an estate in Azabu in Tokyo that his father Masayoshi had purchased.

In addition, I would speculate that Matsukata’s personal desire was amplified by his contact with Monet. Monet, who is known as the initiator of Impressionism, was already becoming a nationally renowned painter in France at that time. On his fifth visit to Europe in 1921, Matsukata visited the house of Monet through the introduction of his relative. Monet’s house was filled with many ukiyo-e collections. It is likely that Monet told Matsukata with great passion how much he loved Japanese art and how much his paintings were inspired by Japanese art.

I do not know whether Matsukata liked Monet’s paintings from the bottom of his heart. But I believe he thought, “This famous painter in France loves Japanese paintings so much. I will buy a lot of paintings by Monet and take them back to Japan so that people can enjoy seeing them.”

Yashiro Yukio, an art critic who was studying in Europe at that time (he held many important positions, such as professor of the Tokyo Fine Arts School [currently Tokyo University of the Arts] and director of the Institute of Art Research [the predecessor of the National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo], and is called Tashiro Yuichi in my novel) was an advisor to Matsukata regarding purchasing paintings. Yashiro wrote about his interactions with Monet and Matsukata in his book.

Matsukata offered to buy dozens of works displayed in his atelier, including Water Lilies and On the Boat, in bulk. Surprised, Monet said with great excitement, “Do you love my paintings so much? I don’t want to sell the paintings I have at home, but I will sell you those paintings because you are so eager.”

Another famous episode says that Matsukata and Yashiro encountered a great painting widely acknowledged for its excellence in 1921.

They saw Bedroom in Arles by Vincent van Gogh at the famous Galerie Paul Rosenberg in Paris and then Parisiennes in Algerian Costume or Harem by Pierre-Auguste Renoir at another gallery. Excited by its excellence, Yashiro said to Matsukata, “This is an exceptional masterpiece. You should definitely buy it and take it to Japan.” But Matsukata frowned and did not take him up on his suggestion, saying “What is this?” Matsukata left the gallery in anger and went home. But when Yashiro, disappointed that he had failed to obtain a masterpiece, visited the gallery again after a while, he found that Matsukata had been shrewd enough to buy Bedroom in Arles and Parisiennes in Algerian Costume or Harem.

Art patrons

In the 1920s, from the end of World War I to the Financial Crisis, Paris saw the arrival of a celebratory age full of vigor called Les Années Folles when Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau worked actively. Riding on this wave, many Japanese businessmen and intellectuals went to Paris.

At the time, a lot of businessmen thought of patronizing artists who had talent that they did not have themselves. In addition to Matsukata, another art patron was Ohara Magosaburo, the president of Kurashiki Spinning Works (currently Kurabo Industries). Ohara said the following to a painter named Kojima Torajiro in his hometown, Okayama, and sent him to Europe: “You are a good art connoisseur. Go to Europe and purchase good items. I will give you as much money as I can.”

Kojima discovered Annunciation by El Greco at a gallery in Paris in 1922, spent a large amount of money on the work and brought it to Japan. In 1930, Ohara opened the Ohara Museum of Art in Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture, collecting modern European paintings that Kojima had brought from Europe. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York opened in 1929, which suggests how far Ohara was ahead of the times. It is nothing less than a miracle that we can enjoy seeing Annunciation in Kurashiki today.

Even today, there are books saying that businesspeople should be artistically cultivated displayed in bookstores. At that time, however, Japanese leaders had a stronger sense of crisis and mission. Many of them thought, “Japan must not only build up its military and economic capabilities, but also raise its cultural and artistic levels in order to be able to compare itself to and compete with Western powers. It is embarrassing and humiliating that the country has no domestic art museums.”

Yashiro, mentioned above, introduces the following scene based on a story he heard from Yoshida Shigeru. When Hayashi Gonsuke, the Japanese Ambassador to Great Britain, Yoshida and Matsukata met in London in 1921, Hayashi said to Matsukata, “Matsukata, you are very rich, but you will lose your money soon and go bankrupt. You should therefore buy a lot of oil paintings for Japan now. It will serve the country well in the future.”

What Hayashi said turned out to have some truth. Matsukata, who was pressed to repay debt due to his ailing business in the wake of the battleship recession amid disarmament after World War I and the Showa Depression, stepped down as the president of Kawasaki Shipbuilding Company in 1928. He was forced to give up his dream of building the Kyoraku Art Museum.

Collection keeper

In this section, I would like to introduce the fact that a Japanese man successfully protected a collection of 400 works left in Paris for Matsukata during World War II. This man was Hioki Kozaburo, an ex-pilot.

Hioki was originally a naval officer. When he did well as a great pilot of an aviation corps., he was headhunted as an engineer for Kawasaki Shipbuilding Company by Matsukata, who predicted that a new era of airplanes, not ships, would soon arrive. Hioki, who was on a temporary transfer to a company in Paris at the time to work on research into aircraft engines, married a French lady, and Matsukata entrusted Hioki with a task when he returned to Japan. Hioki later spent the rest of his life as an art curator.

As World War II intensified and the Nazi German military finally invaded Paris, Hioki left Paris and took shelter in a house in a small village called Abondant 80 kilometers from the city with the collection.

Because Hioki left no records, it is not known what happened after that. Since I have an office in Paris, I stayed there for a long time and gathered information in Abondant. I believe that I was able to get pretty close to the truth.

The house where Hioki used to live still stands in Abondant today. I asked the person who now lives in the house to allow me to look inside. I investigated old documents and found that the name of his wife was Germaine and that Hioki, who lost her during World War II, put up the house for sale.

While I was gathering information in Abondant, I came across a small château opposite the house. After the fall of Paris, Abondant was occupied by the German military. The German military used the main buildings in each village as posts. For this reason, I assumed that the château was also used as a military post and made an investigation. My assumption turned out to be correct. That is, Nazi soldiers were stationed close to Hioki’s house.

The Nazis called the modern art of the time “degenerate art” and oppressed it thoroughly. If the Nazis had noticed the existence of the Matsukata Collection, what would have happened? As the war situation became even worse, remittances from Matsukata to Hioki were cut off. Overcoming numerous difficulties, including hardships in life, the psychological warfare with the Nazis and the death of his wife, Hioki protected the collection to the end. In my latest novel, I described the truth of Hioki that I got close to in my own way.

The diplomatic warfare to get the Matsukata Collection back finally started after World War II. As French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman said to Yoshida, “I may be unable to get some works back to you,” France turned out to be shrewd as a major cultural country. In 1953 Yashiro, who became an expert in the history of Western art, went to France again and asked Georges Salles, director of French Museums, whom he had known for many years, to return Bedroom in Arles and Parisiennes in Algerian Costume or Harem in particular. These were the two works that Yashiro obtained by asking Matsukata to purchase them for Japan. Bedroom in Arles was so important, however, that it was concluded that the work could not be taken out of France. In addition, a total of seventeen paintings, such as Still life with Fan by Paul Gauguin and Mont Sainte-Victoire by Paul Cézanne, were not included in a list of works to be returned and were reserved in France. As a result of patient negotiations, however, the Japanese side succeeded in getting Parisiennes in Algerian Costume or Harem back. In April 1959, just two months before the opening of the NMWA, a total of 375 paintings and sculptures arrived at the port of Yokohama.

Bedroom in Arles by van Gogh, which is now called “Treasures of the Musee D’Orsay,” will come to the latest exhibition, “The Matsukata Collection.” I suggest that you enjoy looking back at the history of Matsukata and Yashiro encountering these two paintings in Paris, appreciating Parisiennes in Algerian Costume or Harem as well.

In addition, you should not miss Water Lilies and Reflections of Weeping Willows by Monet in the latest exhibition. These are among the paintings that Matsukata inherited directly from Monet. But while they were stored at the shelter in Abondant, they were damaged considerably, and their whereabouts remained unknown without being returned to Japan as damaged works. In 2016, however, the paintings were miraculously discovered in a corner of the Louvre Museum and were returned to the Matsukatas. What a dramatic incident that was!

The 60th anniversary of the NMWA provides you with the perfect opportunity to look back on the fact that a businessman named Matsukata Kojiro gave away all his property to collect Western artworks for young Japanese people, and that people protected the art collection for Matsukata and worked hard to get the works back.

Translated from “Sekai saiko ‘Matsukata Korekushon’ cho nyumon—Kokuritsu seiyo bijutsukan wo unda jitsugyoka no suki na jinsei (A basic guide to the greatest Matsukata Collection in the world—The unusual life of the businessman who produced the National Museum of Western Art),” Bungeishunju, July 2019, pp. 212–219. (Courtesy of Bungeishunju, Ltd.) [September 2019]

Keywords

- Harada Maha

- Utsukushiki orokamonotachi no tableau

- Matsukata Kojiro

- Kawasaki Shipbuilding Company

- Kawasaki Heavy Industries

- Matsukata Collection

- A One-Hundred-Year Odyssey

- National Museum of Western Art

- NMWA

- Yoshida Shigeru

- Robert Schuman

- Frank Brangwyn

- Claude Monet

- Yashiro Yukio

- Vincent van Gogh

- Hioki Kozaburo

- Abondant, Paris