Bonsai as Minuscule Garden

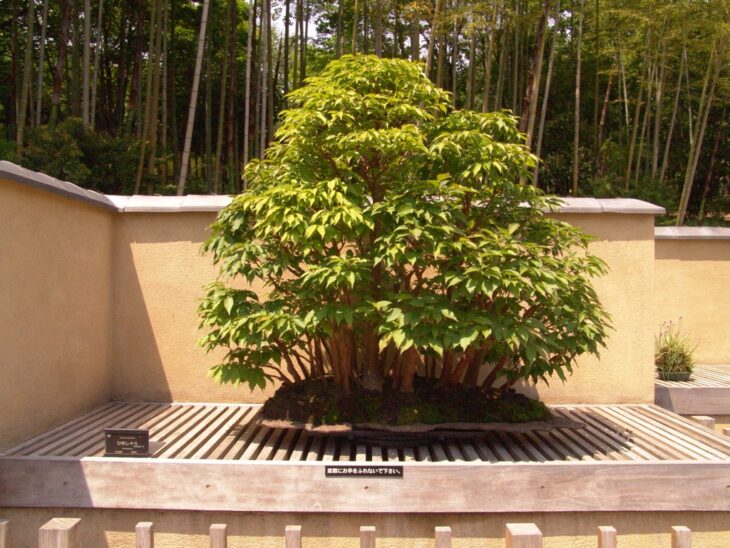

Himeshara (Stewartia monadelpha) bonsai (Showa Memorial Park)

Photo by the author

Yoda Toru, Chief, Curators Division, Toyama Memorial Museum

Bonsai is a culture in which a potted plant is cultivated to remain small, requiring a lot of time and effort to shape. At minimum, bonsai needs care, such as watering, every day, and it also needs pruning, wiring, and sometimes removing bark with a tool. It is a process of creating a living landscape with a small tree in a shallow pot. Therefore, bonsai can be considered a garden. With limited living space in urban areas, we sometimes see people enjoying and treating bonsai as their garden in places such as the balcony of an apartment.

A style called bonsan preceded bonsai in the Kamakura period (1185–1333). It was a kind of miniature garden composed of trees and stones that let people enjoy the view and experience the garden as if they were on the same scale. Bonsan were usually placed on designated shelves in the gardens at houses of the nobility. They were treated like matryoshka dolls, being a small garden inside a bigger garden. The popularity of bonsan gradually diminished, but one of today’s bonsai styles, ishizuke bonsai (bonsai grown in or on a rock), can be seen as a descendant of bonsan. There was another potted tree style very similar to present-day bonsai called hachinoki, in which a single dwarf tree was cared for over a long period of time. Tsurezuregusa (The Harvest of Leisure, written by Yoshida Kenko) suggests that people twisted trees for aesthetic reasons in the end of the Kamakura period, and preferred this eccentric style. The preference was promoted in the Edo period (1603–1867), and extremely twisted trees were created. This style is called tako-zukuri or magemono-zukuri, and it started disappearing after the Meiji period (1868–1912).

The unique philosophy of bonsai in the present day was established between the end of the Meiji period and the Showa period (1926–1989). The bonsai world began aiming to mimic nature and follow the rules of nature. This was distinctive from tako-zukuri, which was directed towards an artificial and formative art. Such emphasis on nature was probably influenced by naturalism in Western literature. The modern bonsai world practices collecting trees that grow up into complex forms in the wilderness, which is called yamadori, and values the natural aspects of the bonsai that are beyond what humans can create. A characteristic of bonsai is that it cannot be classified as either “nature” or “art.” Perhaps the contemporary meaning and potential of bonsai is latent within the aspects of it that extend beyond that modern framework.

Is a bonsai tree a garden?

Yoda Toru

Bonsai is a cultural activity in which trees are planted in pots, maintained in a miniature state, and shaped by the application of time and effort. It is based on daily watering, and involves pruning with scissors and wiring, and sometimes even tasks such as using mechanical tools to shave the tree’s bark. It is the activity of creating a landscape using trees in the limited space of a pot, and a bonsai tree can be considered a kind of garden. In fact, even in urban areas with limited living space, we can see cases of people enjoying bonsai on apartment balconies in a similar way to gentle gardening.

Another feature of bonsai is that they are crafted to be small using artisanal techniques. Astonishment at such bonsai can be found in travel accounts by foreigners during the Meiji period (1868–1912). Even today, it seems that people in other countries still view bonsai as a lingering “mystery of the Orient.” Keywords such as “Zen” are often used in relation to bonsai. They may serve to turn the elements of bonsai that can’t be logically explained into a “black box.”

Close up of the base of the same tree, Himeshara (Stewartia monadelpha) bonsai

Photos by author

The way of seeing bonsai as a minuscule garden also has historical validity. In my book, The Birth of Bonsai (Taishukan Publishing, 2014), I traced the birth of bonsai to the vogue for Chinese culture that occurred from the end of the Edo period (1603–1867) to the Meiji period. Japanese people who had never seen the real China tried to recreate the China of their dreams by collecting imported products. This took form as a linked set of Chinese hobbies such as literati painting (also known as nanga or southern painting), sencha (green tea), and bonsai. However, the “pre-history” of bonsai is a style called bonsan that preceded it, having been established in the Kamakura period (1185–1333). This is also a kind of hakoniwa (box garden), created by combining trees and stones. From records such as the Inryoken Nichiroku (Inryoken’s Diary), written by a Shokoku-ji temple priest in the Muromachi period (1336–1573), it seems the viewer of these became small and as if lost in the landscape. However, this type of bonsan was placed in the garden of an aristocrat’s mansion on a shelf level with the engawa veranda. In other words, there was a little garden within a garden, and this matryoshka-like nested structure was likely characteristic. That such bonsan remained in the gardens of feudal lords during the Edo period can be confirmed from such works as Akasakaoniwazugajo (Wakayama City Museum), which depicts the garden (now part of the Akasaka Detached Palace) of the Kishu Tokugawa family. Although this type of bonsai gradually became less popular in modern Japan, ishizuki bonsai (bonsai grown in or on rocks) can still be seen today and can be considered its descendant. In this sense, such things as hakoniwa, which were popular in the Edo period, may also be seen as a descendant of this type of garden.

There was also a type of potted plant called hachinoki (potted tree). This was a single tree tended over time, rather like today’s bonsai. However, from a description in the Tsurezuregusa (also known as The Harvest of Leisure by the Japanese monk Yoshida Kenko, 1283?-1352?) we can infer that during the late Kamakura period (1185–1333), people deliberately made twisted trees. In fact, it appears that there was a strong element of enjoying the unusual shapes of the trees. This penchant for appreciating twisted trees developed further during the Edo period (1603–1867), and trees of extremely distorted shape were created. Often referred to as tako-zukuri or magemono-zukuri, this style, however, became modified and disappeared from the Meiji period on. Initially, this was due to the influence of the vogue for China I mentioned earlier. But in time the influence of Western ways of seeing “nature” became more important, something I will address below.

Bonsai as a hobby

However, bonsai also includes elements different from gardens. For one, it is a practical hobby involving the enjoyment of daily watering and care. Sometimes, different problems occur, such as the death of branches and other plant parts, so it becomes necessary to make changes such as modifying the shape of the branches. It is the attitude of taking pleasure in patiently dealing with the inconvenience of a living thing that doesn’t do what we want. This is the important essence of bonsai.

Another element is acquiring bonsai to build a collection. we can see potted trees lined up in rows not just in the portrait of a daimyo’s garden mentioned above, but also in woodblock prints that show the gardens of common people. In one way, collecting many different varieties and looking for pots to suit those trees matches the Japanese mania for collecting things.

From the Meiji period to the Showa period, bonsai was especially popular with important people from the political world. These include such statesmen as prime ministers Saionji Kinmochi (1849–1940) and Okuma Shigenobu (1838–1922), who are the ancestors of postwar prime ministers such as Yoshida Shigeru (1878-1967) and Kishi Nobusuke (96-1987), and former Speaker of the Lower House Kono Yohei (1937–), to mention a figure of recent years. Owning a bonsai and displaying it in one’s garden was a kind of social status symbol and various bonsai exhibitions functioned as a place for showing off.

On the other hand, a feature of bonsai is that it can be taken up and enjoyed by anyone who has a tree, soil and a pot, irrespective of class. In fact, Uchiyama Chotaro (1804–1883), a gardener [and a chrysanthemum florist] active from the Edo period to the Meiji era, is known for successfully getting to know the heir of the Toyama domain at a temple festival, later taking the name Hanaya [florist] Taiko[1].

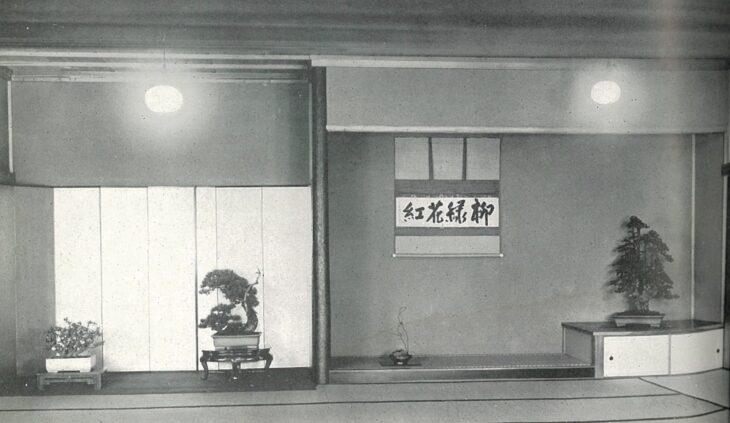

A bonsai exhibition in the Showa period, prewar

All Japan Art Bonsai Photograph Collection, Hakubunkan, 1939

Bonsai as art and as culture

A famous tree known as “The Shimpaku (authentic oak) of the Satake Family.” The white branches are called “jin.”

Nihon Bonsai Taikan, Sokai, 1938.

Compared to bonsai as a hobby, from the perspective of art it is quite difficult to discuss bonsai’s formative qualities. The first notable feature of a living and continually growing bonsai is that it is never “finished.” What’s more, trees have a longer lifespan than humans, so they are transferred between people and passed down through the generations. Because a new owner may make major modifications, the bonsai cannot keep a uniform beautiful form. This is readily apparent from bonsai of deciduous trees (classified as “miscellaneous trees” in the bonsai world), which change with the seasons.

I have encountered some people connected with bonsai who like to call it an “art.” And I’ve seen a tendency for people to stress jin (bare-stripped branch) and shari (barkless trunk), which highlight formative qualities by leaving dead branches white, in a way that makes them akin to contemporary art. However, the root of the word “art” is the Latin “ars,” which means “a technique to create something that does not exist in nature.” In Western aesthetics, “natural beauty” not created by human hands and “art” created by humans are in opposition. I majored in art history at university, so I feel a certain resistance to terming the daily changing appearance of trees “art.”

For example, the karin (Chinese quince) in the collection of the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum in Saitama City belonged to the early modern industrialist Nezu Kaichiro (1860–1940) in the early Showa period (1926–1989), and its appearance has been preserved in photographs. Although slender at the time, it was later owned by former prime minister Sato Eisaku (1901–1975) and then by Kishi Nobusuke. It currently belongs to Saitama City. About 100 years have passed. Now the trunk has grown thick and sturdy, and the raised roots are gripping the soil. The form created by the growth of the tree itself does not seem to fit into the category of “art” as a human activity.

Also, as I have mentioned, bonsai is a culture that was suddenly created in the modern era, and its historical underpinnings are insubstantial. In particular, its Edo-period history of “potted trees” being modified and made into bonsai has resulted in a structure with no classic masterpieces. If cultural maturity is interpreted as a process of establishing a classical style, then breaking away from it and changing to a newer style, at times bonsai can resemble a premature baby that has failed to reach cultural maturity.

Often there is tendency to try and explain the spiritual underpinning of bonsai by claiming it is Zen Buddhism or with the terms wabi and sabi, which are used in the tea ceremony; but this serves to obfuscate bonsai’s immaturity. From the end of the Edo period when bonsai was created through the Showa and Heisei (1989–2019) periods, the bonsai world has neglected to look at itself and discuss “what bonsai is.” It has not constructed a bonsai theory that can be understood by people uninterested in bonsai. This contrasts with the history of the tea ceremony world, which tried to set up tea utensils as works of art and theorized them with the keyword “wabi.”

The gap between nature and human artifice

Nevertheless, one feature that has shaped the principles of bonsai is how, from the Meiji period to Showa period, the bonsai world historically adopted “nature” as one of its models and sought to reproduce it. From a historical perspective, this is in marked contrast to the tako-zukuri or magemono-zukuri of the Edo period, which sought artificial beauty of form. This emphasis on nature may have been influenced in part by naturalism derived from Western literature. In the modern bonsai world, bonsai artists have adopted a method known as yamadori, in which they harvest trees that have developed complex shape in the natural world, respecting the parts of the tree that are beyond the reach of human creativity. In other words, they take elements that are not human from the natural world.

What’s more, in bonsai the vitality of trees is sometimes felt in a way somewhat different from nature. For example, the Goyomatsu (Pinus parviflora) in the collection of the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum in Saitama was initially prepared as a bonsai, but lost its shape after its branches died. Yet subsequently, the tree’s growth caused the trunk to rise in a complex form, acquiring a special beauty that transcends human intent.

This absence of human control is also common when planting gardens. Bonsai, however, brings out this feature more clearly by merging the grown tree and plant pot stages. So, this feature is an element that cannot be categorized as either “nature” or “art.” It is precisely this aspect, which does not fit into the “modern framework,” where the contemporary meaning and possibilities of bonsai are latent.

Translated from “Tokushu: Kochiku 4 no Niwa he — Gokusho no niwa, Bonsai (Imaging the Gardens of Building Mode 4: Bonsai as Minuscule Garden),” Habitat Building History (HBH) Vol. 4, May 2022 (Courtesy of Habitat Building History) [September 2022]

The original article (in Japanese) appears at the HBH site: https://hbh.center/04-issue_02/

Keywords

- Yoda Toru

- Toyama Memorial Museum

- bonsai

- garden

- landscape

- artisanal

- nature

- art

- Zen

- Chinese culture

- bonsan

- hakoniwa

- box garden

- hachinoki

- ishizuki bonsai

- rock bonsai

- tako-zukuri

- magemono-zukuri

- twisted trees

- hobby

- status symbol

- jin

- shari

- wabi sabi

- tea ceremony

- yamadori