Art in Daily Life: Transmitting the Culture of “Public Bathhouse Mural Paintings” to the Future

Kawai Kaori, nonfiction writer

On the walls of Kurabu-yu, a public bathhouse located in Nakano Ward, Tokyo, a red and a blue Mt. Fuji stand tall. Tanaka Mizuki, the artist behind this mural, shares her thoughts on the work she creates.

Photo: Nakamura Osamu

A blue sky and Mt. Fuji viewed over water. Murals featuring these motifs are typical of sento (public bathhouses) in Tokyo and the surrounding Kanto region. Yet today, there are only three professional public bathhouse mural painters in all of Japan. One is in his 70s and one is in his 80s. The youngest, Tanaka Mizuki, is 40 years old and is the only female bathhouse mural painter.

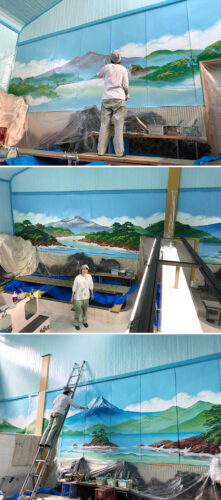

Tanaka Mizuki at work in the Misuji-yu bathhouse in Taito Ward, Tokyo. Tanaka constructs the scaffolding herself.

Photos at Misuji-yu: Komamura Yoshikazu

“Practically speaking, whether or not there is a mural in a public bathhouse doesn’t have much impact on the purpose of taking a bath,” says Tanaka. In other words, bathhouse murals are not a necessity. However, they do serve as a place for a bather to fix their gaze, Tanaka explains. “Public bathhouses have many regular customers, and to them the same mural seen every day can appear different depending on their state of mind. The murals bring intrigue to the bathhouse experience.”

Bathhouse murals are typically repainted every few years. Some are repainted annually, while others go 7 or 8 years before a change. However, most bathhouse murals are replaced every 2 to 3 years. The purpose of repainting is to give customers a sense of freshness and renewed inspiration.

“In Fujiko Fujio A’s autobiographical manga work Manga Michi, there is a scene where the protagonist notices that a bathhouse mural has been renewed. Discovering changes in a familiar place we regularly visit makes us more aware of the passage of time. As we grow older, each year seems to pass by more swiftly. When the painting in our usual public bathhouse is replaced, it awakens us to the passage of time,” says Tanaka.

Does Tanaka feel any sadness when replacing the murals she has so painstakingly created?

“Since my apprentice days, it has felt natural to repaint or replace the murals,” she says. “By changing the composition and motifs in line with an owner’s requests, I can feel my skills gradually improving, and it allows me to explore new territory. I have a positive outlook on it.”

At the core of Tanaka’s thinking lies a question posed by her father, who was an art journalist, while she was in university.

“Bathhouse mural painting is not ‘Art’ but ‘Paint,’” he told her.

Her father is no longer alive, but for almost 20 years Tanaka has continued to ponder the meaning behind those words.

Apprenticeship as a public bathhouse mural painter sparked by graduation research

Tanaka stepped into the world of public bathhouse mural painting during her third year as a student majoring in art history at Meiji Gakuin University.

“For me, up until that point, ‘Art’ meant visiting art museums, standing in front of the works and thinking, ‘I have to understand the concept of this artwork.’ However, during my time at university, as I listened to various professors, I learned that art forms are things to be enjoyed as aspects of everyday life. Japanese western-style painters in the Meiji period (1868–1912) experimented with how to enjoy painting in their daily lives. For example, they hung their paintings vertically and displayed them like hanging scrolls. While searching for such viewing methods, I became interested in public bathhouse murals as a way to appreciate ‘paintings in the spaces of everyday life,’ and I started researching them,” she explains.

Tanaka visited numerous public bathhouses as part of her research, and wrote a graduation thesis titled “Rethinking Bathhouse Mural Paintings in Public Bathhouses: The Standardization of the 20th Century ‘Mt. Fuji’ Motif.” At this time, she learned how Japan’s public bathhouse mural painters were aging and about the difficulty they faced finding successors.

“Truly outstanding art history researchers might approach their studies with a certain level of distance and objectivity. However, after completing my thesis, I strongly felt the desire to preserve bathhouse mural painting as a cultural tradition. And if there was no one else doing it, I thought, ‘Why not me?’ That’s how I embarked on this path.”

Tanaka took on a job as an apprentice to a public bathhouse mural painter. She says at first she was amazed that a mural measuring around 10 m x 5 m could be completed in just one day. Work starts with carrying in the equipment and finally progresses to the task of painting the sky.

“When I was told for the first time to ‘paint the sky,’ my master didn’t give me detailed instructions on how to do it. Even if I was told to ‘learn by observing,’ I often felt down because I didn’t understand what that meant. However, as I continued to experiment and paint, I realized, ‘Ah, I see. It means constantly approaching the work with a sense of inquiry.’”

Tanaka emphasizes the importance of this sense of inquiry when learning by observing. She questions, for example, whether creating a specialized school for painters to acquire the necessary skills would lead to them losing sight of the work’s essence.

“Experiencing mistakes and unpredictable situations gives birth to ‘questions’ within oneself, and seeking answers to those questions should lead to the creation of new value for a craftsperson,” she explains.

Tanaka aims to turn the experience of dealing with unpredictable situations into a strength. Seeking the shortest distance to the correct answer won’t lead to an individual’s own answer, she says.

“Every time I paint with all my strength and think that I can’t do more, but whenever I revisit a bathhouse to repaint, I look at the mural and think, ‘I can do more.’ It’s a cycle of repeating that process. I despair about it every time! Looking back at past works is like looking at my adolescent self,” she says.

At such times, the legacy of her predecessors becomes helpful.

“There are many times I’ve made mistakes and had regrets, but I’ve always learned by observing what other painters created. And when I’ve had uncertainties or economic concerns about the job of painting, I have tried to think of my situation from the perspective of the long history of Japanese art. By researching how painters in the past made a living, with a sense of listening to them, certain things become clearer,” she says.

“Salvation” public bathhouses: Communication during the COVID-19 pandemic

Such thoughts and concerns about uncertainty in life are often encountered at public bathhouses.

“Through casual conversations with the grandmothers at a public bathhouse, you can catch glimpses of their life stories. Many talk openly about their struggles. They share stories with a touch of humor, saying things like, ‘I had surgery recently, and this area still hurts’ or ‘Getting older makes everything more difficult.’ They discuss challenging topics that can arise in life, such as marriage, childbirth, divorce, or illness.”

Tanaka became pregnant and had a child during the COVID-19 pandemic. At an unstable time for society, she found herself feeling particularly vulnerable, physically and mentally.

“I was exposed to a sense of vulnerability that I had forgotten, and my perspective on the world changed completely. I was able to experience the feeling of needing to empathize with others in similar circumstances as a vulnerable person,” she says.

Life throws up all kinds of challenges. Tanaka sees public bathhouses as a place where people can face those challenges and imagine how to live going forward. That’s why she herself is a bathhouse customer.

“Family-like relationships are formed at public bathhouses, and there is an unspoken kindness that accepts vulnerability. For example, when a mother with a baby seems to be struggling, an elderly woman washing nearby might say, ‘Let me watch the child while you wash your body.’ Others hand out homemade ohagi (sweet rice balls coated with red beans) to regular customers after bathing,” she says.

Was the social culture of public bathhouses not affected by the “silent bath” of the COVID-19 pandemic?

“While silent bathing was expected, I believe that communication continued through eye contact and by regular customers just reaching out a helping hand. During a time when even going outside was discouraged, visiting public bathhouses within walking distance from the home and briefly enjoying bathing while seeing others in the neighborhood enduring similar hardships on a daily basis, provided a certain kind of relief,” she says.

In a rapidly changing society, the unchanging nature of public bathhouses, the people who frequent them, and the bathhouse murals—they all played a role in soothing the hearts of many, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Tanaka.

I want to convey the appeal of public bathhouses and bathhouse mural painting to young people

By the way, has Tanaka found the answer to the question posed by her father?

“When I start to see a possible answer, I hesitate because it leads me to reconsider what art and public bathhouse mural painting truly are. I haven’t found the real answer yet, so I continue to question and search,” she says.

How will the culture of bathhouse mural painting be passed down in the future?

“I hope that bathhouse painting remains a culture that continues indefinitely. When I turn 60, I want to be in an environment where there are still people capable of creating public bathhouse murals 30 years into the future,” Tanaka explains.

To achieve that, it’s important to first make young people aware of the charm of bathhouse mural painting.

“I want young people to visit public bathhouses and experience the atmosphere and the fascinating aspects of bathhouse murals. On the other hand, in this unpredictable world, ten years from now I don’t know how the enjoyment of public bathhouses will have evolved. However, I feel certain that the essence of the bathhouse, which Japanese people love dearly, will continue to resonate with future generations.”

Translated from “Tanaka Mizuki: Nichijo no nakani aru aato ‘Sento penki e’ no bunka wo Mirai e (Tanaka Mizuki: Art in Daily Life—Transmitting the Culture of “Public Bathhouse Mural Paintings” to the Future),” Wedge, May 2023, pp. 88-90. (Courtesy of WEDGE Inc.) [July 2023]

Keywords

- Kawai Kaori

- Tanaka Mizuki

- sento

- public bathhouse

- public bathhouse mural painting

- sento penki-e-shi

- public bathhouse mural painter

- cultural tradition

- communication

- COVID-19

- silent bath