Kemari and the Japanese: A History of the Acceptance and Maturing of Foreign Sports

At Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto, one of Japan’s World Heritage sites, “Kemari Hajime” is held every January, in which kemari is performed.

Tanigama Hironori, Professor, Toyo University

It is often said that Japanese people began to adopt sports from overseas in the Meiji period (1868–1912). However, the history of foreign sports in Japan is long, and the leisurely aristocrats of ancient times were among the first to experience sports from the continent and enjoy them as an elegant hobby.

Kemari, or shukiku (an ancient football game, 蹴鞠), is the most long-lived and widely played foreign athletic game in Japanese history, played by people from all walks of life. In the ancient Imperial Court, a variety of sports were performed by competitors from the provinces during the festival days of the year, while the Emperor and senior aristocrats watched and enjoyed them. Kemari, on the other hand, falls into the category of “sports to do,” played by the ancient nobility themselves.

In ancient China, there were several types of kemari (cuju in Chinese), including a soccer-like format in which players compete for points at the goal and a goal-less passing format. Of these, kemari, which is a static passing game, was popularized in Japan’s aristocratic society, which valued elegance.

Japanese kemari is a sport in which several players, known as mariashi (kemari player, 鞠足), kick up and pass the mari (ball, 鞠) continuously without letting it fall to the ground. Trees called kakari-no-ki (showing the standard height to which the ball should be kicked, 懸の木) were planted at the four corners of the playing area, and when the ball touched the branches and leaves, an irregularly curved ball was created, increasing the difficulty. To get around this, advanced skills such as voice coordination and formation were developed.

Records of the existence of kemari date back to the Nihon Shoki (Japanese Chronicles, compiled in 720). On the new year’s day of 644 (Kogyoku 3), Prince Nakano Oe (Nakano Oe no Oji, the future Emperor Tenji, 626–672) and Nakatomi no Kamatari (614–669) met and became close through a kuemari (kemari, 打毬) meeting held at Hoko-ji temple (predecessor of Asuka-dera temple). It is said that Prince Nakano Oe’s shoes came off and Kamatari picked them up and offered them to him. It can be seen that kemari was a means of socializing among the aristocrats of the time (although there is no solid evidence that they played kemari).

Later, as kemari became established in aristocratic society, many rules appropriate to court culture were established, including techniques, etiquette, costumes, facilities, and tools. Kemari is a sport in which players track the number of times their mari score has increased, but obsessing over records alone was considered indecent, and mariashi who combined advanced technique with graceful behavior were worthy of praise. After the cloistered government period (from the late 11th century for just over 100 years), the emperor and retired emperor began to participate in kemari themselves. Among them, Emperor Go-Shirakawa (1127–92) was the first to perform kemari while standing in a mari-ba (ball garden, place for kemari, 鞠庭).

Toward the end of the Heian period (794–1185), mariashi, who were celebrated as masters of kemari, also appeared. Fujiwara no Narimichi (1097–1162), a court nobleman who was active in the first half of the 12th century, was a person who left his name to posterity as Kikusei (talented player of kemari, 鞠聖). Kokon Chomonju (A Collection of Remarkable Tales Old and New, compiled around 1254) states that Narimichi’s kemari techniques were at a level that surpassed those of ordinary people.

Behind the scenes, the people who supported the elegant sporting life of the ancient nobility were the craftsmen who were hired to make the equipment. In particular, kemari balls (mari), which originated overseas, were not something that anyone could easily make on their own, so there was a need for craftsmen. In the second half of the 12th century, a business type called mari-kukuri was established to produce mari.

Even in the era of the samurai government, aristocrats continued to love kemari. A person who greatly contributed to the development of kemari after the Middle Ages was Emperor Go-Toba (1180–1239), known as the Kemari Master. In 1208 (Shogen 2), the “Kemari-do (way)” was established with Emperor Go-Toba as its leader, and three iemoto (head families) were born: Namba, Asukai and Mikohidari. In this way, kemari, beloved by the upper aristocracy, rose to the world of high-class entertainment and established an unshakable position.

In the Middle Ages, samurai also began to practice kemari, but it was still the aristocrats who took the initiative in kemari culture. For the Kamakura shoguns of the Kamakura period (1185–1333), who dominated politics, kemari is said to have been a means for the samurai to function effectively in aristocratic society and to exchange nobles and soldiers.

The Muromachi period (1336–1573) was influenced by the fact that successive shoguns loved kemari, and kemari became a tashinami (taste, knowledge of performing arts, etc.) of senior samurai. Eventually, kemari permeated the local samurai society as if it followed their cultural life.

In the Sengoku period (1467–1590), kemari survived as a means of social interaction among powerful warlords. According to the Nobunaga Koki (Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga), Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582) held a kemari meeting with Imagawa Ujizane (1538–1615), a master kemari player, in 1575. He himself enjoyed watching the performance.

Jesuit missionary Luis Frois (1532–1597) wrote in Nichi-O Bunka Hikaku (Comparison of Japanese and European cultures; original title in Portuguese, Tratado das contradições e diferenças de costumes entre a Europa e o Japão), compiled in 1585 (Tensho 13), “Among us, we play the ball with our hands. The Japanese play with their feet.” Frois’s observational eye caught sight of kemari, a ball game that used the feet that existed in Japan at the time.

In the 15th century, marikukuri, who made kemari mari, became independent as full-time craftsmen, and kutsu-tsukuri (shoemakers), who made shoes exclusively for kemari, also flourished. Without demand, artisans would not exist as suppliers, so their existence speaks volumes about the deep roots of kemari in medieval society. As the turbulent era of the Sengoku period came to an end and the era of peace began, the world of sports also entered a period of great change. The development of the monetary economy supported the rise of the common people, and a new era of sports centered on the common people had arrived.

Kemari was passed down from the ancient nobility to the medieval samurai, and in the early modern period it became popular as a ball game that could be enjoyed by common people. Kemari played by ordinary people was called jige-mari (kemari games played among common people who are not allowed to enter the mariba for the noble people) and became popular.

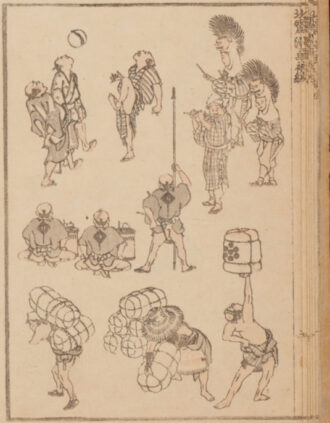

Ordinary people playing kemari as depicted in Hokusai Manga (three people on the top left of the diagram).

Source: Hokusai Manga, Vol.1, Digital Research Archives, Tokyo National Museum

In the early modern period, assistant instructors called mari-mokudai (鞠目代) were placed under the iemoto heads of kemari, and a certain number of them were stationed throughout the country. Mari-mokudai instructors are those who excel in kemari techniques and play the role of instructing kemari enthusiasts in various places and connecting headmasters and lower-level disciples. In some cases, a commoner becomes a mari-mokudai, and a commoner mari-mokudai also participates in the kemari shogun’s inspection held at Edo Castle.

Hokusai Manga (Vol. 1, published in 1814) shows a commoner wearing a traditional Japanese kimono and kicking a ball while wearing zori sandals. It can be said that kemari, which was originally a court culture that was supposed to be very particular about costume and etiquette, began to take on the role of a pastime that commoners could play in casual clothes.

In the 18th century, craftsmen began to appear in Edo (former name for Tokyo) who made sports equipment. Imayo shokunin zukushi hyakunin isshu (a parody book of Hyakunin Isshu, published in the Kyoho era [1716–1735]) describes Edo craftsmen of the early 18th century by industry. Among them is a mari-ya shop which made mari for kemari.

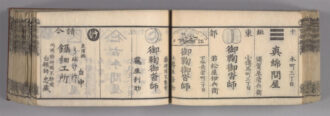

Imayo shokunin zukushi hyakunin isshu depicts craftsmen preparing the mari at a mari-ya, accompanied by a parody of the Hyakunin Isshu waka poem.

Source: Kondo Kiyoharu [author] et al., Imayo shokunin zukushi hyakunin isshu, Yoneyamado, 1939. National Diet Library Digital Collection

https://dl.ndl.go.jp/en/pid/1117916/1/10

Edo Kaimono Hitori Annai (Edo Shopping Guide, published in Osaka in 1824), a guide to Edo shops published in 1824, included an advertisement for the Kemari tool stores, indicating that the stores had locations throughout Edo City.

Some of the influential kemari tool merchants had close ties to the iemoto. It is said that they also had the role of accepting disciples and instructing them in kemari under the authority of the iemoto. The head of the kemari family planned to expand the kemari market by entrusting the acquisition of new disciples and technical guidance to merchants who had both the ability to supply tools and customer information.

Three Kemari equipment store advertisements appearing in the Edo Kaimono Hitori Annai (a “mari” is drawn at the top of two of the advertisement spaces).

Source: Edo Shopping Guide, Volume 2

Edited by Nakagawa Gorozaemon, Edo Kaimono Hitori Annai, Volume 2. National Diet Library Digital Collection

https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/8369321/1/93

Kemari, a foreign sport, successfully entered pre-modern Japanese society with sensitivity to the prevailing winds of the time. Throughout the ancient, medieval, and early modern eras, kemari remained an effective tool for bringing people together and continued to be loved by the people of the time. As a result, it can be said that a large sports industry was finally established, with the head of the school at the top.

Just like today, the lives of pre-modern Japanese people were colored by a variety of sports. Kemari is just one example.

Supotsu no Nihonshi: Yugi, Geino, Bujutsu (Japanese history of sports: Games, performing arts, martial arts), recently published, is an attempt to examine the sports that existed in the Japanese archipelago in chronological order: prehistoric, ancient, medieval, and modern. We hope that you will pick up a copy of this book and experience the dynamic sports activities of the pre-modern Japanese people.

Translated from “Kemari to Nihonjin (Kemari and the Japanese),” Hongo, No. 169 (January 2024), pp. 31–33 (Courtesy of Yoshikawa Kobunkan)

Keywords

- Tanigama Hironori

- Toyo University

- sports

- foreign sports

- Japan

- kemari

- shukiku

- cuju

- football

- Imperial court

- aristocratic society

- Nihon Shoki

- Heian period

- masters of kemari

- iemoto

- Fujiwara no Narimichi

- Emperor Go-Toba

- samurai

- Oda Nobunaga

- Imagawa Ujizane

- Luis Frois

- Hokusai Manga

- Supotsu no Nihonshi: Yugi, Geino, Bujutsu (Japanese history of sports: Games, performing arts, martial arts)