A Genre in Literature Where Human Nature Is Laid Bare

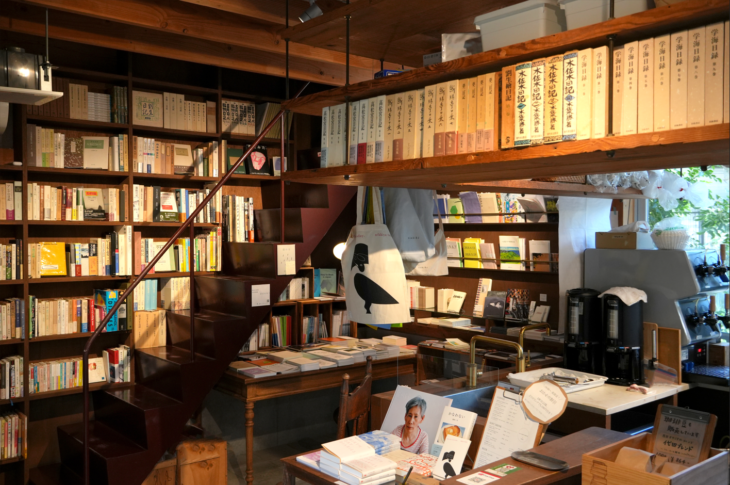

“Nikki-ya Tsukihi” diary bookstore and coffee stand

Photo: Courtesy of NUMABOOKS

The act of looking at daily life

Three years have passed since I opened “Nikki-ya Tsukihi,”[1] a store specializing in diary literature, in the BONUS TRACK[2] commercial area in Shimokitazawa, Tokyo. I myself like reading diary books, and have been involved with diary books for some time, including introducing them in magazine articles and publishing them through my own publishing company, NUMABOOKS, but I had never thought of opening a specialty store. However, when I became involved in the overall management of BONUS TRACK, I had an idea that it could work as a store along with a coffee stand.

A diary is a piece of literature that plainly records one person’s daily activities. In an era where people are conscious of cost performance, and in a world where life is all about pursuing economic rationality, I have always thought that the number of people who need diaries will increase.

At the end of the day, writing about what you experienced and felt that day is an opportunity to realize that even days you thought were boring can be rich. Also, when I come into contact with other people’s diaries written in this way, I feel somehow encouraged by the fact that there are people who live their lives feeling the same way. It was also at a time when I was beginning to think that as we live in a backward society, it is necessary to look at our daily activities, and that it would be great if more people kept and read diaries.

From diary little press to professional writer

Another reason for opening “Tsukihi” is that diary books are easy to sell. It all started when I suddenly realized that I was buying only diary books at a literary flea market (an exhibition and sale event where exhibitors sell their own works by hand) that I often attend. For some reason, diary books caught my attention more than novels. I thought it was because I like diary books, but when I thought about it, I realized that wasn’t the only reason.

Purchasing a novel by an unknown writer whose name is unknown is a difficult process. On the other hand, when we are interested in the diary books of people with specific occupations or special experiences, the name of the writer does not have much influence. In other words, I thought that if we stocked a lot of little presses (booklets produced in small numbers by individuals or small groups, also known as zines) of diary books by unknown writers, they would sell.

The prospect was right. The overwhelming majority of Tsukihi’s sales come from little press diaries that are not distributed commercially. Many people come to the store looking for something that is not sold elsewhere and can only be purchased here, and people who stop by on a whim also buy diary books by non-famous authors.

Of course, even among them, there are differences in sales. The diary books that sell best are those that are not sold in other bookstores, by people who are somewhat known on social media or who are already a bit famous.

Even if they are not, diary books with unique themes or those who are interesting as writers will sell little by little. Twice a year, “Tsukihi” holds a “Diary Books Festival,” a market exclusively for diary books, and there have already been several cases where diary books of people who had stalls there caught the attention of editors, were published as commercial publications, and then went on to become full-fledged authors. Uemoto Ichiko, a photographer and writer, had a self-published booklet that opened the door to commercial publication, and she is now a popular writer with books published by major publishing houses. She still sells her own diaries as zines, and these sell well in the “Tsukihi.” I think it would be interesting to see if this becomes a place where the second or third Uemoto is born.

There are many different types of diary books, and as exemplified by a novelist Fukazawa Shichiro (1914–1987)’s famous essay collection Iwanakereba Yokattanoni Nikki (Diary I wish I had never told you about) (1958), there are many books that do not really feel like diary books even though they have “diary” in the title. Therefore, for “Tsukihi,” we decided to select books based on the criteria that “dates are included.” We offer a wide variety of publications, from commercial publications to self-published publications, while being flexible enough to purchase diary books that are obviously diaries even without dates.

Coronavirus pandemic boosted the boom

When we decided to open the store, we did not anticipate the coronavirus pandemic that would soon follow, but as it turned out, the pandemic brought even more attention to diaries. It was like we were trying to create demand and it came naturally from the other side.

In times of crisis, when the world is undergoing major changes, such as wars and epidemics, people’s sensitivities become more sensitive, and they become conscious of the need to record what has happened. Many diary books that have already been published were written under such circumstances, so I think it was natural that an increasing number of people started keeping diaries or turned their own diaries into diary books during the coronavirus pandemic. Amidst this momentum, we happened to have just opened a store specializing in diary books, and we came to attract attention as a part of the diary book boom. Extraordinary times are not limited to wars or pandemics. There are also many diary books in circulation in which people record their extraordinary experiences, such as when they took care of their parents or when they were involved in a crime. However, this is not to say that we only place importance on diary books written under such extraordinary circumstances.

Many of you may have felt impatient to write about some special experience for your summer vacation picture diary homework when you were in elementary school, but I think it doesn’t have to be special. It is much more interesting to write about an ordinary day, and it is when you write about an ordinary day that you can see how a person sees things and how they write. We would rather focus on such interesting aspects.

In “Tsukihi,” we hold a workshop where participants walk around the city for a day, come back, write diaries, and share their diaries with each other. It goes without saying that even if they have the same experience, each person sees, thinks, and remembers something different, and the way they write about it is also very different and very interesting.

How much to write and who is allowed to read it

In the past, a diary was something you kept in secret and only for yourself. Nowadays, more and more people are posting their diaries on the Internet or selling them as zines. It is a very strange trend, but there seems to be quite a gradation among people as to how far they are willing to be open about it.

Some people don’t want to show their diary to anyone, while others are fine with allowing their close friends to see and read it. Some people don’t want only those close to them to see it, but they want someone to read their work because they have taken the pains to write it. “Tsukihi” operates an online community called “Tsukihi-kai,” where you can post your diary anonymously every week and it will be distributed only to members of the e-mail newsletter, where strangers can read it and give their impressions. Participants of this service are people who want to be read by someone. On the other hand, people who blog or publish their work are probably people who don’t care about anyone reading their daily life.

Those who do not want only their family to read their work may be afraid that their daily activities will be restricted. If their family members, whom they see daily, know their true thoughts, it will interfere with their daily lives.

The poet Ishikawa Takuboku (1886–1912)’s Romazi Nikki (Diary in roman letters), which he wrote in Roman letters so that his wife would not read it, clearly describes his affair, but even if it is not a big secret, it can cause problems.

Let’s say you write down a small feeling in your diary, saying something like, “I didn’t like my family doing this.” Even if you don’t hate it so much that you want it fixed, if the person reads it, there’s a chance they’ll say, “Okay, I’ll fix it.” That is uncomfortable. If you are concerned about the impact on the people you live with, you will not be able to write freely what you think. This could be said to be a difference in the view of family. People who think, “Even though they are family, they are strangers, and I want a minimum amount of distance in order to live together,” do not want their family to read their diary. And people who believe that everything should be open to their families think it’s okay for their families to read their diaries.

In other words, many people consciously draw the line as to how far they should write. When writing as an expression, there is always the purpose of communicating to someone, but people who write diaries are aware of whether they are communicating to just themselves, close friends, or an unspecified number of people. Even Takuboku had feelings that he wanted to convey to someone, but he didn’t want those close to him to know about it, so he probably used Roman characters that could be read by those who could read.

While the influence of social media has reduced resistance to having one’s writings read by others, I feel that more and more people are able to control the line between “I can tell others this much, but only this much within myself.” Everyday, everyone who uses social media is conditioned to go back and forth between their “presented self” and their “authentic self.”

A diary is a letter from your past self

Actually, even though I am working to spread diary books, I never make my diary public, nor do I show it to anyone else. I am writing only for myself to read.

I always read my diary back. In fact, I could even say that I write my diary for the purpose of reading it again. The timing of re-reading varies, sometimes I read last week’s diary and other times I dig out last year’s diary to see what I was like a year ago.

When I read it a while later, I find encouragement from my past self, saying things like, “Ah, I managed to survive that time,” “Because I worked hard then, I can overcome the hardships I’m having now,” and “That was a surprisingly good thing to say.” An idea that once occurred to me and I wrote down can sometimes serve as a hint for my current work. After all, I am rereading my diary and keeping a diary to see what has changed and what has remained the same.

I write only for my own reading, so I don’t leave anything that I would feel bad about reading back later. Just because it is a diary doesn’t mean you have to write the truth. When I write about negative events, I try to digest them in my own way and conclude, “This is just the way it is in the end,” rather than writing down my feelings as they are.

When exchanging work e-mails, there are times when I feel annoyed with the other person’s writing, or when I feel the urge to complain about something. It would be inappropriate to express such feelings directly to the other person, so I write them down and paste them into my diary. To avoid offending the other person when I read the pasted sentences later, I distinguish them by shading them in gray or downgrading them by one letter. I call this “making a memorial service.” I save the effort I put into writing the text and offer it as a memorial service, but I do not send it back or read it again. These writings quietly accumulate on my computer. This is my unique way of using a diary, and I like it very much.

Uchinuma method, benefits of a diary

Every day, social media is full of people’s moments of confusion. Even when I look at them, I think. Impulsive feelings of anger never make people feel good. The same goes for me. I don’t want to read it again and feel bad. But I also don’t feel good about keeping my vague feelings in my heart. That’s why I write it down and throw it away where no one can see it. Perhaps because of this, when I’m too busy to write in my diary for a while, my condition starts to deteriorate. I often find myself thinking, “I haven’t been feeling well lately… That’s because I haven’t been writing in my diary!” Some people feel physically unwell if they don’t run every day, but for me, my mental health deteriorates if I don’t write in a diary.

Writing a diary helps me to organize my thoughts, to chew over ugly feelings and reassess them objectively, and to properly end what has happened to me. When I write, I feel refreshed and can move on. It’s tricky, though, because the busier I am, the more I have to write, but I can’t. The reason why more and more people are keeping diaries is probably due to the effects of a stressful society.

Background of the work and the author’s personality as revealed by the diary

Even if you just say you like reading diaries, there are many ways to enjoy them. Among them, I particularly like diary books by novelists whose works I have become familiar with. When I was in junior high school, I read Albert Camus’s three-volume series Camus’s Kamyu no Techo (Notebooks), which led me to discover the interest of diaries as a literary art form. When I heard that the diary he kept while writing Ihojin (The Stranger [L’Étranger]), which I had read earlier, had been published, I became curious and read it. I was able to see his character, the flow of his thoughts, and the background of The Stranger and I enjoyed solving the mystery of the novel world.

Susan Sontag’s posthumously published diaries, Watashi wa Umare naoshiteiru (Reborn: Journals and Notebooks 1947–1963) and Kokoro wa Karada ni tsurarete [Volumes 1 and 2] (As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks, 1964–1980), are also interesting. I am not sure if these are the diaries that Susan Sontag herself wanted to publish, but when I hear that a diary of an author I am interested in has been published, I want to read it. It is not because I want to take a peek into her private life, but rather because I am interested in what a person who can write such a work is thinking in her daily life. I also get excited when I see the title of a book she was reading at the time. I think to myself, “Oh, Sontag was living at the same time as the author of that book.” I love the feeling that the world of the work and the real world are linked, and the resolution is raised.

Humanity transcends time and place

As you can see, there are many ways to enjoy diary books, but I think the most appealing thing about them is that you can “get in touch with the part of a person that is closest to the person himself/herself.”

In creative works such as novels, stories, and essays, the author’s intentions are reflected in all expressions. Even if things seem to be written casually, they are necessary expressions to flesh out the characters. In other words, what is written there is only what the artist intended to depict. On the other hand, a diary written simply to record daily records reveals the true nature of the person. This is because it is an act that is done without purpose. A person who transcends time and place becomes visible. That’s really interesting.

Recently, the popular “Seikatsu-shi” (Life history) series (edited by sociologist Kishi Masahiko, with three editions published in Tokyo, Okinawa, and Osaka) , which compiles the personal histories of ordinary people in the form of narrative transcriptions, has become a popular topic of interest. The “Seikatsu-shi” series is a little different from diary books. Although they are the same in that a person’s daily life is written down, the act of writing directly by the person himself or herself and the act of talking to someone else and putting it into writing are completely different. Also, while a diary is a series of detailed descriptions of the events of the day, a life history is a condensed summary of a life story. Since it is told to others, the line of “let’s show this much” is clearly drawn, and it tends to be dramatic in a certain way. Both continuity and resolution are very different. I think the charm of writing about things that are nothing, even to the person themselves, is something that only diary books can offer. That is exactly what attracts me to diaries. Diary books are filled with trivial daily life that novels don’t bother to write about. Each person’s daily life is different. This is true whether it is written by someone from a foreign country or someone from a long time ago, and in that sense, there is no difference in how interesting diary books are whether they are written by people of all ages or modern times. No matter how far away someone is from us, we can sometimes feel the same way and see things the same way.

I thought to myself, “What humans think and feel are the same thing,” and on the other hand, I was surprised to find out, “Even when we look at the same thing, we feel so different.” The same is true when writing. I think there’s a joy in writing about the parts of yourself that are closest to you in keeping a diary. Of course not everything will be written. However, I believe that diary literature is a rare literary genre in which human beings themselves are revealed most openly.

Compiled by Takamatsu Yuka

Translated from “Ningen ga Mukidashi ni naru Bungei-janru (A Genre in Literature Where Human Nature is Laid Bare),” Chuokoron, January 2024, pp. 106–113 (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [September 2024]

[1] The store name “Tsukihi” is the Japanese word for dates. [2] BONUS TRACK is a new style shopping mall in Shimokitazawa, Tokyo, which opened in April 2020, featuring unique restaurants, stores selling goods, co-working spaces, shared kitchens, plazas and galleries. Official website (in Japanese) https://bonus-track.net/

Keywords

- Takamatsu Yuka

- Uchinuma Shintaro

- NUMABOOKS

- Nikki-ya Tsukihi

- BONUS TRACK

- Shimokitazawa

- diary book

- diary

- diaries

- Uemoto Ichiko

- Fukazawa Shichiro

- Ishikawa Takuboku

- social media

- presented self

- authentic self

- Albert Camus

- Susan Sontag

- “Life History”

- Masahiko Kishi