China’s Robust Ambitions: Conversation on Xi Jinping’s Logic of Expanding Hegemony—Decoding China’s Maritime Strategy and Human Rights Issues

Kawashima Shin, Professor at University of Tokyo and Masuo Chisako T., Associate

Professor at Kyushu University

COVID-19 Has Changed Chinese Politics

Prof. Kawashima Shin

Kawashima Shin: Let’s first take a look at the circumstances and challenges that China is facing during the COVID-19 pandemic. China was slow with the first response to COVID-19 infections, but successfully contained them in March and April 2020. Moreover, in parallel with the pandemic response, efforts were also made to thoroughly promote economic recovery and enforce the rule of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

With regard to the economy, reforms of the GDP structure are underway centering on domestic demand alongside efforts to build domestic supply chains for state-of-the-art industries through the “dual-circulation strategy” and the Export Control Law, all the while dealing with the decoupling between the United States and China. Moreover, they secured 2.3% economic growth in 2020 and have a target of 6% or more for 2021. I believe the CPC government is strict but is in a position where they can count on popular support to some extent.

These results have also led some to argue that an authoritarian regime is more effective in containing infectious diseases. However, the relative success of Chinese policies should be viewed against a background of successful community building, such as the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission of the Communist Party of China, which was promoted to increase public order, as well as experiences of using networks and data in what is called the “digital surveillance society.” Is it possible for other developing and emerging countries to match those resources and institutions? From this perspective, I think it’s unlikely that the so-called China model will immediately spread across the world.

Prof. Masuo Chisako T.

Masuo Chisako T.: My view is that COVID-19 has completely changed the phase of Chinese politics. By mobilizing medical teams and the military all over the country, Xi Jinping gathered state power in his own hands. Also, although the economy is normally a matter for the “premier” in China, Xi started actively intervening in it during the COVID-19 pandemic. He began to control private companies very strictly.

Xi Jinping has always thought that economic and security policies ought to be devised together. This is why he shifted the Chinese economy to be controlled strictly by the CPC during this national crisis. At the moment, Chinese politics is under his personal dictatorship. China has changed completely during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kawashima: That was accelerated by the United States. Following 9.11 and the Lehman shock, China sees the COVID-19 pandemic as the next thing to weaken American national power. It also looks like they will catch up with American GDP earlier than the 2030 prediction. The mistakes of the Trump administration have become a tailwind for China.

Prof. Masuo, as an expert, how do you view China’s bolder stance in the oceans and on the border with India during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Masuo: China has clashed with India, strengthened control over Hong Kong, oppressed the Uighurs, put more pressure on Taiwan, and formulated the Coast Guard Law targeting areas like the Senkaku Islands. I consider all of these to be under the same logic. Xi Jinping is holding up high ideals as a communist, and trying hard to build an ideal state within the border, he believes. For this aim, he is formulating the “Territory and Space Program” and establishing complete governance in all areas he considers to be Chinese. Those in China who don’t submit to this are pressurized, and those who don’t agree with the national borders and jurisdiction waters suggested by China face serious struggles with the Chinese. I think all of the recent hardline measures in domestic politics and foreign relations can be understood in this context.

A Focus on Anti-Poverty Measures and Environmental Issues

――The National People’s Congress (NPC) convened in March. What drew your interest?

Masuo: I paid attention to the outline of long-range objectives through 2035. That’s equivalent to three five-year plans. This fifteen-year program isn’t something regular and has a big significance, I believe.

Xi Jinping has repeatedly mentioned that the CPC-led political system is to the advantage of China. Recently, he’s also been using the keywords “design economy” and “security in a united manner.” China has the edge over liberal countries when it comes to the CPC’s comprehensive ability to determine the distribution of resources and to mobilize the people nationwide.

The long-range objectives through 2035 aim to unify economic development and security further as well as to realize “Chinese Peace.” For this purpose, the CPC controls the core of the Chinese economy. In terms of security, I think they intend to realize a modern Great Wall by enhancing defenses along China’s land and sea borders and by protecting themselves internally with various advanced technologies acquired through economic development.

Economy and security are inseparable. Xi Jinping’s China Model involves the CPC systematically advancing both. A massive trend toward this has started through the COVID-19 responses.

Kawashima: I focused on Xi Jinping’s emphasis on the outcomes of anti-poverty measures. He claimed that a lot had been done with anti-poverty measures in farm villages. He also emphasized that the five-year plan had accomplished so-called xiaokang, which means “decent living” (US$3000 GDP per capita), in all regions in the same year as the 100th anniversary of the founding of the CP.

Another recent feature is the extreme frequency with which he refers to ecology and other environmental matters. China is also working to build a clean economy and deal with climate change.

In order to maintain international competitiveness, China has to influence economic global standards and revise them to China’s advantage, while presenting themselves as joining the international order of free trade and allowing the people of China to enjoy advanced abundance. Environmental topics are directly related to images of people’s abundance, so if China can become a world leader in environmental issues, they will also gain new business opportunities.

Economy and Security Risks

Masuo: Many Japanese have an image of China as a bad country. But Chinese think that China is becoming better and better. In fact, Xi Jinping has been working hard to raise the living standard of the Chinese people. Compared to before, environmental pollution has gone down considerably. Many measures against air pollution including PM2.5 (particulate matter 2.5 thousandths of a millimeter or smaller in diameter) were taken quite quickly while the ones to protect the natural environment are advancing at the same time. If Japanese people were to actually see this, I’m sure they would be surprised at how much China has improved in the last ten years.

Real efforts are also being made to alleviate poverty as local officials are directed to “deal with the problems of the common people.” As part of the so-called Five-Sphere Integrated Development, efforts are being made for achieving economic, political, cultural, social, and eco-environmental development in a harmonious way. Xi Jinping is trying to create good government as he envisions it, using the latest technologies and forms of control. It’s as if he wants to be remembered by history as a good emperor, and in reality, he’s an emperor that does his job quite well.

How we should approach China is a rather difficult question. Many Japanese wonder if it’s possible to decouple from it. Meanwhile, China is recently announcing that they should boost China’s international position by inviting different countries onto the economic and technological platforms created and dominated by China.

Kawashima: As you said, the Xi Jinping administration is building China’s economy in the name of the “dual-circulation strategy.” That model is geared toward making the world reliant on the Chinese market by keeping state-of-the-art industries within China and opening the Chinese market to the world to be able to influence the world economy while keeping GDP centered on domestic demand. This is what will allow China to dominate in economic security. China tries to hurt Taiwan by restricting banana imports while making themselves immune to sanctions imposed by the other country. This also makes it necessary to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

So, what does it mean for Japan to be deeply involved with this Chinese economy and depending on the Chinese market? It goes without saying that we can’t ignore China, the world’s second biggest economy. However, it might be a future “risk” to have areas and fields that rely solely on the Chinese market. Even if a Japanese company develops something in China, there’s a risk that it can’t be exported due to the Export Control Law.

There’s a policy of dealing with economy and security comprehensively in China, but the state’s security is actually prioritized higher than the economy. This means that it’s dangerous to pass judgment on the Chinese economy based solely on economic reasoning. Aside from direct factors like the East China Sea, territory and missiles, China-related risks include structural risks of economic mutual dependence.

In fact, China spoke about economy and security at the 2020 Central Economic Working Conference and again emphasized economic security at the NPC in March 2020. That covered a variety of elements, such as food, energy, resources and finance. The United States is also decoupling with regard to advanced industries that can be used for both military and civilian purposes, so Japan isn’t really in a position to keep talking about a separation of politics from economics. So, what should we do? Japan is standing at a crossroads about how to engage with China.

Masuo: I’m also thinking that we’re in a phase when the lives of Japanese people are being affected by trends in Chinese politics, also economically.

The Coast Guard Law for Effective Control of Contested Waters

――China enforced the “Coast Guard Law” on February 1, detailing the duties and powers of the China Coast Guard, which is in charge of maritime law-enforcement. It’s controversial because of Article 21 that allows the use of arms and the expulsion of foreign military and government vessels from the “jurisdictional waters” that China has defined unilaterally.

Masuo: This might surprise anyone who isn’t a China watcher, but Xi Jinping is careful to advance things in an orderly fashion on the basis of procedures. He is moving China forward by preparing legislation, creating internal rules for the authorities, developing institutions, and formulating long-term programs. The Coast Guard Law was created because no legislation on maritime law-enforcement existed previously. Therefore, the lawmaking is not a problem in itself.

Nonetheless, the Coast Guard Law regulates what future actions China will take in the “jurisdictional waters” that they themselves claim. Half of these waters are contested with other countries. Normally, negotiations on how to draw the maritime borders would come first, but China is moving ahead on the premise that all the waters under its claim belong to China.

Kawashima: For the time being, the Xi Jinping administration is building constitutional government with the aim of institutionalizing governance, enhancing stability, and preventing corruption. The Coast Guard Law is part of that. Many organizations were consolidated and the CCG was made part of the Armed Police, so the People’s Armed Police Law was revised in June 2020, and it was on that basis that the Coast Guard Law was formulated. There’s much to be said if we were to compare the Coast Guard Law with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), but the content about the jurisdictional waters is problematic.

Jurisdictional waters were defined in this draft. They make up a space that differs from the UNCLOS understanding, extending beyond territorial waters to also include contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and continental shelf. This content was deleted in the end, but jurisdictional waters were actually stipulated to be “internal waters, territorial waters, contiguous zone, EEZ, continental shelf, and other waters under the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China” in a public notice of the Supreme People’s Court enforced in August 2016. I think the Chinese were also aware that this Coast Guard Law would be criticized by neighboring countries. Yet the logic of domestic politics required legislation, so I think we will see a “salami slice strategy” of gradually legal substantiation. Some say there was no beforehand explanation of the Coast Guard Law, but for the Chinese, this can be explained with the logic that “there’s no need to explain domestic laws” and if they’re told “it contravenes UNCLOS,” they’ll probably answer “we have different interpretations.”

Masuo: The Coast Guard Law suggests the direction China will take over areas like the Senkaku Islands and the South China Sea in the future. Xi Jinping plans to bundle all past national development programs and launch the “National Territory and Space Program” this spring, which also includes the plans for China’s claiming jurisdictional waters. I’m sure they were in a hurry to get the Coast Guard Law in place to prepare for that.

I should also mention that while the “Island Protection Program” that has been formulated in 2012 has not included a section on the Senkaku Islands, that’s likely a part of the new program. The Chinese formulation of those programs usually gets into gear in the summer of the previous year, so the environment surrounding the policymakers around that time is of extreme importance. The more they have a sense of crisis that “things should not continue like this,” the more intense the programs will be. The preparation for the long-range objectives through 2035 was launched in the summer of 2020 amid a sense of crisis that China’s economic lifeline might be cut off due to the high-tech offensive carried out by the United States.

|

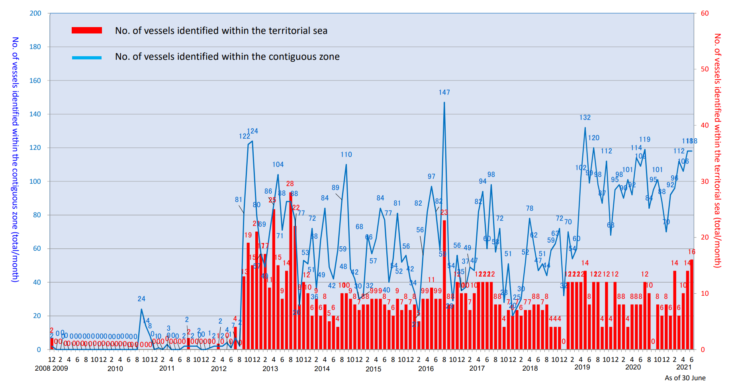

The numbers of Chinese government and other vessels that entered Japan’s contiguous zone or intruded into territorial sea surrounding the Senkaku Islands |

Considered in the same context, the Senkaku Islands cannot be excluded from the new Territory and Space Program. The tension surrounding the Senkaku Islands will likely become more severe the closer we get to the target year of 2035. The Coast Guard Law also made it obligatory “to protect […] ‘facilities and structures’” in Chinese jurisdictional waters for the Chinese Coast Guard. They might be thinking of building new structures and expand existing oil and gas facilities there.

In China, once a program has been made, it can never be softened or canceled at the discretion of the bureaucrats themselves. It has to be implemented until Xi Jinping or someone else at the top says “Stop!”

What Japan can do is create a situation where Xi Jinping considers “it’s best to stop or slow this” for his country. Although the defense on-site has to be carried out mainly by Japan alone, it doesn’t mean that we have to deal with China all by ourselves. We can gather and show materials from all over the world to persuade China that this isn’t a good way forward for your country.

Kawashima: This is relevant to all countries that neighbor Chinese waters, including in the China Sea and the South China Sea. Japan could perhaps build horizontal networks with such countries and have information sharing mechanisms, but also needs to collaborate with the United States.

Masuo: With regard to the United States, the Chinese long-range objectives through 2035 came about from an anti-Trump position. We already have the President Biden administration, but the objectives have already been installed in the bureaucratic system in China. The United States is also grappling with the challenge of how to deal with China’s authoritarian regime that is not moving closer to the United States but rather further away.

Kawashima: Some say the antagonism between the United States and China will become like the Cold War, but the dependence of the American economy on the Chinese economy remains strong. Considering the closeness of relations between the two countries, it’s highly unlikely that we will get something like the US–Soviet Cold War any time soon. Rather, we should be seeing at critical turns patchy appearances of issues relating to military–civilian advanced industries, the Taiwan issue in military security, and human rights issues in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and elsewhere.

Masuo: I think China’s next objective in East Asia is Taiwan. How much will the United States keep its commitment? If the power relationship between the United States and China is reversed or the United States becomes preoccupied with domestic politics, they might not necessarily be able to commit so much in Taiwan. The same goes for the East China Sea. Compared to Taiwan and the South China Sea, the value of the Senkaku Islands for Chinese security is smaller, but it is very valuable in Xi Jinping’s political narrative for domestic society. So we really can’t let our guard down.

The Need for Japanese Responsiveness

――How should Japan respond to China as they expand their hegemony?

Masuo: The Chinese are realists, so they won’t back down unless you make a show of force. At the same time, they have an extremely strong desire for recognition to be respected by other countries. It’s easy to think that “China is a country of power,” but the determinants for China’s actions are more complicated. As such, we have to come up with an international strategy to induce China to work in collaboration with us explaining that “this is the best way if you want to be respected by the world.” It will become important to run several strategies in parallel as we deal with China.

Kawashima: I agree. We will need to consider China’s intentions and capabilities from their perspective as much as possible. Before we say they’re “strange” because they differ from our perspectives, we should first understand where they are coming from and respond based on a grasp of their intentions and capabilities. When it comes to their expanding hegemony, there is a ground plan of how China intends to deal with Chinese territory, including the sea, so we need to know that as well. To do this, Japan needs to boost our capacities to gather and analyze intelligence. I also think we need more comprehensive national power, including maritime security, defensive, economical, and technological power, so that we can respond in practice. We need the power to respond when dealing with China, which has such a strong realist aspect.

Masuo: I think that’s exactly what we’re not doing well. For example, eyes have been on the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS), so I suspect our Ministry of Defense is investigating it. Yet, China’s vision for the BDS is so grand. To understand the full picture, Japan will need to work interministerially or inter-disciplinarily.

The services using the BDS are diversifying. For example, BDS end units installed on fishing vessels are automatically informing the authorities of their locations and safety every hour. Conversely, there is an AI that analyzes the results of weather and maritime observations by Chinese ocean satellites, so that fishers at sea can receive information about where there’s a lot of fish and the current market price of different kinds of fish. If you connect your smartphone with the unit, you can always chat with your family on shore, and I hear satellite phone only costs about 2 cents per minute. Because there are many added services, people are happy to use it. With this system that shows consideration for the people allows the Chinese government to communicate with fishing vessels in real time. Vessels that follow instructions can be immediately paid rewards in e-money. It has become possible to turn fishermen into de facto militias.

Kawashima: This is true not only for fishing vessels, but also commercial ships, the relevant navigation systems, and marine insurance. Marine insurance is an enormous right that has historically belonged to the Anglo-Saxons, but it is supported by a command over navigation system information that links satellites and ship navigation. Behind the gigantic interest of marine insurance stand systems for constantly keeping track of ships across the world. It seems that China is trying to become part of this with their own system. The costs are low, so it is possible that they will compete with, clash with, and differentiate from existing interests.

Masuo: There have been recent observations of Chinese ships turning off Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals across the world. Turning it off is in itself a violation of international rules, so they do keep signaling as of now but erase traces of the movements that took them there. China not only thinks little of international rules but also creates their own standards and is starting to tell others to switch to their systems because they are better. There is an aspect to this of a new rivalry between international standard systems and China’s own systems.

Kawashima: China is working to create a world separate from the systems of the Western societies in the area of information and communications, especially when it comes to providing Internet and location information. Huawei Marine Networks built a submarine cable for the Internet, BeiDou is providing a GPS system, the data of Chinese device users is provided to the government, and that information is used as big data or personal management information. There’s that kind of cycle.

Consumers use these services because they are moderately priced and convenient. Thus, there is even the possibility that developing and emerging countries and even advanced countries flood to China’s side. The dominance of Western countries in the past 150 to 200 years is being lost to China in a number of areas.

Masuo: I think that’s true. The current systems are not as solid as the West thinks. I can imagine that BeiDou will spread globally and penetrate places like Africa quite well. The cheap and convenient systems are very attractive to countries that aren’t wary of China.

However, I doubt that Japan has been able to analyze this situation comprehensively. Everything is fused in Xi Jinping’s China, but the Japanese are not able to respond uniformly. It seems no one in Japan is trying to decipher the policies and strategies of the CPC by considering the implications from the BeiDou technologies. We’re not even aware of what China is trying to do. I think that’s the biggest problem.

Kawashima: Although few, there are those in the Japanese government and the National Institute for Defense Studies who analyze individual issues in China. There are also those researching BeiDou, the submarine cables, and the activities of Chinese fishing vessels. However, I think the real problem is that there is not a properly functioning context or organization for comprehensively and inter-disciplinarily analyzing the capacity to respond to fusion. I wonder how deeply Japan will view and respond to this situation?

Information is somehow gathering in a single place, but there’s not much of comprehensive analysis and reports going up for decision-making. The absolute number of staff is also small.

Masuo: People are discussing under what conditions Japan can exert harmful shooting and defense mobilizations of the Self-Defense Forces based on the assumption that China will try to steal the Senkaku Islands. It’s important to be prepared, but we also won’t be able to respond when things actually happen unless we anticipate a variety of combinations and patterns of Chinese intentions and capabilities. For example, to what extent can weapons be used against civilians if a large number of China Coast Guard (CCG) ships and fishing vessels make their way there at once? What happens if fire is exchanged? Depending on the circumstances, we need to decide our responses in a timely manner. I suspect that China wants to make the situation more complex and delay Japanese decisions. There’s a risk that we’ll fall into that trap.

Japan energetically declares that China is either important or a threat. The influence of such a big neighbor is considerable, so this is true. Yet, one regrettable aspect of a democratic country in the current situation is that researchers are studying whatever areas they like. Unfortunately, the government also does not fund holistic research on China. If we’re worried about China’s future directions, then Japan should also cooperate properly domestically.

If things go on like this, then we might lose the means to resist China before we know it.

Kawashima: Japan thinks we know China well, but China is evolving on a daily basis, so we can’t analyze them properly unless we have a team with enough members. I don’t know who should lead it, but networking and integration is needed at the very least.

Human Rights Issues in Hong Kong and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region

――China is suppressing human rights in Hong Kong and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. How should Japan tackle China’s human rights issues?

Masuo: The suppression of democratic activities is intensifying in Hong Kong, but since this is happening as part of developments in Chinese politics as a whole, it’s difficult to change reality only through criticism. Many Han Chinese also think of the Uighurs as terrorists, so the oppression in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region is seen as a correct action by the CPC regime and the people surrounding it.

What can Japan and Western countries do about this? We have no choice but to take a long-term approach. We have to tenaciously convey the importance of human rights. It’s difficult to turn China around 180 degrees at once, but we might be able to gradually alter their direction by 5 or 10 degrees at a time by persistently explaining the universal value of human rights.

Kawashima: The human rights issues in Hong Kong and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region as pointed out by the West are “interference” in China’s domestic affairs from a Chinese perspective. Although Japan can express their worries and encourage the Hong Kong people, it is likely difficult to change China in any substantial way. However, I do think that Japan has options of acting concretely. For example, Japan can increase the number of Hong Kong students accepted for overseas studies or save those Uighur students who have to leave Japan because they can’t renew their passports due to the wishes of the Chinese government. It might be possible to offer actual support, although small, instead of just issuing statements. Yet, if we’re going to do this, it will require meticulous responses, so it needs to be drafted and institutionalized properly.

Masuo: There are also people in China who are worried about Hong Kong and the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. We have no choice but to maintain dialog with them and sow seeds for thought. It is very possible that all those seeds will bud at once when the trends in Chinese politics change.

Kawashima: Taking on China’s human rights issues takes a lot of courage. We have a global standard for human rights, and if we go back into the history of relations between Japan and China, there are issues for which Japan should be blamed, so there is a risk that they will be brought up again. If we’re going to issue a strong statement to China, then we have to be ready for harsh criticism of our past from China.

I think the Biden administration and other advanced countries will continue to ask Japan to state our position with regard to China’s human rights issues. During the Trump administration, Japan issued a joint statement of “grave concern” over the Hong Kong issue at the G7 Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in June 2020. Yet there was no conformity outside of that. As the human rights issues are becoming entwined with economic matters, such as the issue of Uighur forced labor, we need to think seriously about whether Japan should continue the same policy as up until now.

How to Respond to Xi Jinping’s China

Masuo: Japan has to deal with a China that is on the rise and possesses both economic and military power. In the context of Chinese politics, Xi Jinping is a very able leader. However, he has exerted tremendous pressure to control the domestic situation. Great dispersing forces will likely affect Chinese politics when he goes away. Japan will likely have to face China’s overpowering force head-on for another ten years. Japan has to survive somehow until the arrival of the post-Xi Jinping era. In order to do so, we have to carefully decipher the logic of China, and of Xi Jinping in particular.

Kawashima: There is no major resistance against Xi Jinping from the Chinese people at the moment. The United States has their own goals and China’s position in the world has been rising fairly well. It is true that there are various problems, but there’s also enough there to let them brag that “China is great.”

In this sense, it is difficult to say whether striking tyranny is exercised all over China. We’re at a stage where we can’t claim that the governance is bad simply because it is not institutionally democratic.

Masuo: Yes, the satisfaction of the Chinese general population is high.

Kawashima: Indeed. That’s why we shouldn’t go with the knee-jerk reaction of saying “It’s wrong,” but we need to look carefully to see why the Xi Jinping administration exists and why it is supported. Furthermore, when looking at US–China relations, we also need to doubt whether everything the United States does is correct and everything China does is wrong.

Compared to earlier times when there was a fixed number of overwhelmingly strong powers, we’re currently living in a time with an extreme number of variables. We have to start solving pretty difficult equations where we also consider mutual relations between issues.

Considering Japanese national interests, there will surely be times when we ought to side with neither the United States nor China. There will probably be cases where we join groups of European or other countries, or cases that we simply have to ignore.

Since the Meiji period, Japan has followed Europe and North America and viewed China negatively, and this has become a habit. Yet, we’re now in an era when the erstwhile simplistic framework of separating politics and economy doesn’t work, in the sense of relying on the alliance with the United States for security and being open to all for everything else.

As a country in East Asia, Japan needs to consider what developments in the Korean peninsula, Taiwan, the East China Sea, and the South China Sea will benefit Japan the most, and we need to respond and invest resources to get the scenario we want. If we just keep responding in an ad hoc manner, we might reach a point of no return. Also with Taiwan, we need to do more than express sympathy and come up with something concrete or we might end up actually betraying that trust. I think we should at least make a ten-year plan and need to have long-term, continuous policies and preparedness.

Moderated by Toya Koichi

Translated from “‘Kyoken Chugoku no yabo’ haken kakudaisuru Shu Kinpei no ronri: Chugoku no kaiyo senryaku, jinken mondai wo yomitoku (“China’s Robust Ambitions” Conversation on Xi Jinping’s Logic of Expanding Hegemony—Decoding China’s Maritime Strategy and Human Rights Issues),” Chuokoron, May 2021, pp. 106-117 (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [June 2021]

Keywords

- Kawashima Shin

- University of Tokyo

- Masuo Chisako T.

- Kyushu University

- China

- COVID-19

- Xi Jinping

- Uighurs

- Coast Guard Law

- UNCLOS

- Senkaku Islands

- poverty

- xiaokang

- BeiDou Navigation Satellite System

- Hong Kong

- Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region

- human rights