DYNAMISM OF INTERNATIONAL DIVISION OF LABOR OF THE 21ST CENTURY BROUGHT ABOUT BY REGIONALISM

Kimura Fukunari, Ph.D.

I feel a bit disappointed each time I am asked that simple but important question, “Is trade liberalization actually a good thing?” Theories on international trade, my area of expertise, are here for explaining the need for trade liberalization. Such a question makes me wonder what we have been doing.

There are two ways to approach theories on international trade: one is from the economics standpoint where government is well-distanced from the real world economy and is capable of always implementing optimal political measures; and the other is from the political economics standpoint where political measures are formed through interactions mainly involving the economy. Following these paths makes it theoretically possible to justify free trade reasonably and with convincing evidence, even though it may not be always easy to comprehend. So why then have we been unable to fully persuade the general public? It must be because no sufficient policy debate has been presented in the area of international trade studies in a way suited to actual situations of the constantly globalizing economy.

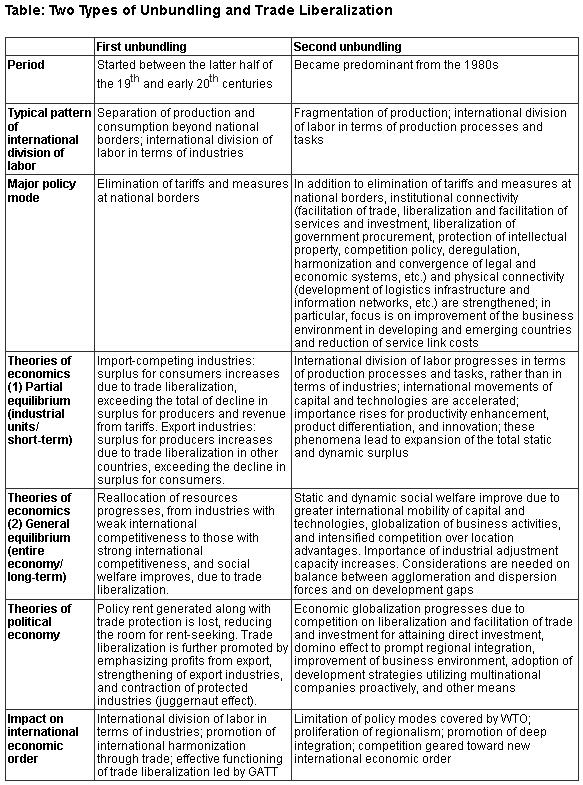

Richard Baldwin calls today’s globalizing economy the age of a second unbundling (fragmentation in units of production processes and tasks). Here we find a completely different form of international division of labor from the age of the first unbundling (separation of production and consumption) that took place in the preceding century. The international economic order required therefore also differs. However, economic and politico-economic analyses have not matured enough to suit the new age. Not only theoretical studies but also political debates and quantification of outcomes of political measures have lagged far behind the actual economy.

East Asia is the area where the second-phase unbundling has most progressed, especially for the manufacturing industries in the form of production networks. Japanese companies have played important roles in configuration of these networks. This is also where the source of Japanese companies’ competitiveness is found. The economic partnership agreement (EPA) Japan concluded with ASEAN countries incorporates various political modes beyond mere tariff elimination for further activating the production networks. It has the potential to serve as a prototype of 21st century regionalism. And competition has now begun among regions for configuring a new model of international economic order. The Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement (TPP) is one such attempt. Economic integration in East Asia also has a potential for exercising leadership.

To begin with, configuration of an international economic order fit for the new age and establishment of 21st century regionalism are tasks for Japan to perform. Yet Japan has not fully understood the historical significance of the new movement and has been concerned only about near-term domestic politics. The situation has accelerated decline of its relative position in international society.

This article seeks to explain the significance of trade liberalization in the new age, using economic and politico-economic theories, clarify its impact on the international economic order, and based on these discussions deliberate the path to be taken by Japan in economic diplomacy.

International division of labor of the 20th century and multilateral trade liberalization

We can start with a review of the conventional type of international division of labor and the corresponding trade liberalization.

The first unbundling, as defined by Baldwin, was triggered by the mass transportation revolution brought about by the steam engine, and took place in full scale from the late-19th century to early 20th century. Division of production and consumption at that time progressed beyond national borders, and international division of labor progressed in industrial units. We can call this the 20th century type of international division of labor.

The international political environment required with the 20th century division of labor was mainly free trade of final goods. In this stage of international trade, emphasis is placed on reduction of transportation costs by transporting in mass, rather than on sophisticated logistics services where precise timing is demanded. Therefore, the policy mode targeted mainly involved tariffs and other measures at national borders.

Economics makes attempts to justify free trade using two slightly different theories, called the partial equilibrium approach and general equilibrium approach. In the former, only one industry is extracted and a short term before inter-industrial adjustments take place is taken into consideration. In import-competing industries, domestic prices fall to a level of international prices if tariffs are eliminated, increasing surplus among consumers. Even though surplus for producers and revenues from tariffs decrease, the rise in surplus among consumers exceeds their total. With export industries, if a simple bilateral model is used, surplus for producers increases due to trade liberalization in other countries. Even though surplus decreases for consumers due to rising domestic prices, the rise in surplus for producers exceeds the decline. In either case, surplus increases for the whole nation if tariffs are eliminated.

On the other hand, the general equilibrium approach addresses the entire national economy and takes into consideration a long term after adjustments have been made among industries. Capital and labor resources are reallocated from industries with low international competitiveness to those with high competitiveness, improving overall economic efficiency and augmenting social welfare.

In theory, there are cases where trade liberalization brings about a decline in the total surplus or social welfare. Examples include the case when the terms of trade change for a large country and when the market fails because of externalities or economies of scale. These are, however, mostly exceptional cases. Trade policies are also not a first-best policy and in most cases bring about new market distortion. For these reasons, free trade is supported as the rule of thumb.

Justification of free trade by political economy supplements the argument. One of the major advantages of free trade is elimination of policy rent generated due to discretionary trade protection. For this reason, once trade is liberalized, the room for inefficient rent-seeking also reduces.

Also to note is prevalence of the apparently mercantilist assumption among the general public that export is good and import is bad, which is wrong from an economic standpoint. This has resulted because producers have an easier time organizing effective lobbying than consumers, and the political costs for adjustment are smaller for promoting export industries than for providing subsidies to uncompetitive import industries. Even if this were actually the case, once export industries are strengthened by trade liberalization and competitive import industries decline, political influence of the export industries will gradually heighten and trade liberalization can be promoted further (the juggernaut effect).

One area of impact of trade liberalization on international economic order, in the context of the first unbundling, is promotion of international harmonization through trade realized by individual countries’ attempts to segregate themselves into industrial units. Looking back on history, multiple trade liberalization led by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT; today’s World Trade Organization [WTO]) proved effective in liberalization at this stage. On the other hand, regionalism was exposed to criticism because its negative aspect, trade diversion resulting from discriminatory treatment to countries outside the region, was emphasized.

International division of labor of the 21st century and two types of “connectivity”

The second unbundling advocated by Baldwin was triggered by the information and communications technology (ICT) revolution, starting in the 1980s. Fragmentation of production progressed beyond national borders, and international division of labor was promoted in units of production processes and tasks. We can call this 21st century international division of labor.

The international division of labor of the 21st century resulted in explosive increase of trade in components and semi-finished products, making logistics services that stress costs for time and reliability indispensable, instead of merely reducing transportation costs by transporting in bulk. The international division of labor among advanced, developing and emerging countries was released from a state that tended to become fixed based on industry-level comparative advantage and came to be developed promptly and boldly in units of production processes and tasks; which also brought significant changes to development strategies.

As production systems came to be developed beyond national borders, the necessary international policies and environmental development measures now address policy modes, which used to be separated as domestic policy, in addition to mere tariffs and measures at national borders. Extremely important here are location advantages to withstand production fragmentation in developing and emerging countries, as well as reduction of service link costs connecting remote production blocks. The policy modes that need to be taken care of for this purpose, in addition to tariffs and measures at national borders, involve extensive aspects related to institutional and physical connectivity.

Policies related to institutional connectivity include various trade and domestic policies for activating the second unbundling – trade facilitation, liberalization and facilitation of services and investment, liberalization of governmental procurement, protection of intellectual property, competition policies, deregulation, and harmonization and convergence of legal and economic systems. Those related to the physical connectivity include a development agenda beyond mere economic integration, such as development of logistics infrastructure and information networks.

Theories need to be reorganized for justifying trade liberalization from economic viewpoints as well. From a partial equilibrium approach perspective, international division of labor progresses in units of production processes and tasks rather than industries, accelerating global shifting of capital and technology as well. As such, the importance of productivity enhancement, product differentiation and innovation essentially increases, and the total static and dynamic surpluses expand when they are promoted. From a general equilibrium approach perspective, static and dynamic social welfare is improved through smoother international mobility of capital and technology, progress in globalization of business activities, and intensified competition over advantageous locations.

When this stage is reached, it becomes more important than ever to promptly and smoothly make industrial adjustments in order to cope with economic changes. The private sector involved with the second unbundling is far more creative and agile than what policymakers speculate. Policy systems that promote, rather than hinder, industrial adjustment will be needed.

Implications on the development gap will also change depending on the balance between agglomeration and dispersion forces as defined in spatial economics. Favorably combining the improvement in locational advantages and reduction of service link costs makes it possible to simultaneously pursue deeper economic integration and narrowing of development gaps, by forming industrial accumulations that serve as the innovation core and expanding production networks.

From viewpoints of political economy as well, trade liberalization begins generating positive economic effects at an increasing rate when things start rolling as in East Asia. Competition over liberalization and facilitation of trade and investment has progressed among developing and emerging countries in relation to acquisition of direct investment and participation in production networks. A domino effect that prompts regional economic integration is also observed. Globalization of economic activities progresses even further through improvement of business environment and adoption of development strategies to proactively utilize multinational companies in developing and emerging countries.

Focusing on regionalism’s flexibility

These movements have significant impact on the international economic order as well. The WTO failed in expansion of policy modes, which it is in charge of, and lagged far behind in establishing the international economic order for the second unbundling. As if to supplement the situation, regionalism has emerged as a more active policy channel.

The discriminatory tendency that regionalism possesses is a problem, but empirical studies have shown that the decline in welfare resulting from discriminatory treatment of third nations in regionalism is in many cases minimal when compared to the positive effects generated by trade creation. The WTO regulations allow discriminatory treatment in trade of goods and services, but there are areas where the principle of most favored nation treatment is at work, such as protection of intellectual property. There are also areas where discriminatory treatment is technically difficult, such as trade facilitation. Many of the policy modes compatible with the 21st century international division of labor have shown an increasing tendency toward regionalism, positively appraising its aspects that can improve the policy environment.

In the past, there were concerns over the spaghetti bowl and noodle bowl phenomena resulting from the overlapping formation of free trade agreements (FTAs). FTAs are an elastic policy channel since they can be concluded in succession without revising the existing agreements. On the other hand, they have an adverse effect of complicating trade policies. However, an increasing number of empirical studies in recent years have found that the negative effects of overlapping FTAs on trade are minimal, and the effects of trade liberalization obtained by concluding FTAs in succession are greater even though this might appear somewhat chaotic.

Bilateral and multilateral FTAs are now being negotiated and concluded at the same time. Several peculiar differences are found between the two. Bilateral FTA negotiations are conducted face-to-face between the two parties, enabling certain areas of interest to be studied deeply. It is also easy to create tie-ups with economic cooperation and other policy modes outside the FTA. On the other hand, multilateral FTAs involve cumbersome negotiations in most cases because a number of countries are involved. Trade and investment covering wide regions, however, may be activated further, and these could also be a powerful tool for establishing international rules. In East Asia and the Asia-Pacific region, the two types of FTAs are, for now, being utilized ingeniously to suit the situations.

As a reference, the implications of trade liberalization in each of the first and second unbundling discussed above are summarized in the table.

Issues for Japan

Movements toward economic integration in the Asia-Pacific region and East Asia, including the TPP, represent attempts to address issues specific to the 21st century. However, due to Japan’s lack of active participation, neither of the attempts has been able to incorporate sufficient measures that respond to current needs.

With the TPP, 24 working groups have been formed by the nine countries in negotiation, for the purpose of discussing a wide range of policy modes. Concerning tariffs, negotiations are reportedly underway on a policy to immediately eliminate tariffs on 95% of the list of items, and ultimately for almost all items, which can be seen as ambitious. However, some claim that other issues specific to the 21st century have yet to be discussed in depth, due also to conflicting positions among negotiating countries. Another point that poses a question about the possibility of the TPP becoming a prototype of 21st century regionalism is the lack of an agenda that is explicitly aware of the production networks formed by manufacturing industries in East Asia.

On the other hand, concerning economic integration in East Asia, the ASEAN+1 hub-and-spoke system has been formed around the ASEAN countries, with the intention of expanding it further into a region-wide FTA. Debates took place between China and Japan on whether to give priority to ASEAN+3 or proceed with ASEAN+6. Recently, however, China seems to have been stirred by the TPP negotiations and has turned to a proactive stance of promptly advancing negotiations rather than being overly insistent on which countries participate. As such, there is a strong chance that negotiations could start by the end of next year. However, looking at this detail, China prefers FTAs with a lesser degree of freedom, based on the existing ASEAN+1 FTA. ASEAN, on the other hand, could aim at an FTA with a slightly higher degree of freedom in order to maintain its centrality in regional economic integration. Whatever the case, under the current situation, there is little chance that measures worthy of being called 21st century regionalism will be immediately incorporated in areas other than tariff elimination.

The 21st century international division of labor is the means that will strongly support Japanese industries, particularly manufacturing, and Japan must participate in the process for establishing the international economic order to further activate this division. Yet it has not been able to effectively utilize the policy channel named regionalism because it still has not resolved the trade protection policy for agriculture, which is a 20th century-type issue. Bilateral EPAs concluded between Japan and ASEAN countries could have functioned as a prototype of the regionalism of the 21st century if they were promoted more strategically. However, Japan preserved trade protection on a wide range of agricultural products, and the result was an FTA with a low degree of freedom in tariff elimination, which serves as an index of FTA quality. As such, an East Asian model has yet to be established. With respect to the TPP, Japan will not be able even to participate in negotiations if it adheres to trade protection on agricultural products. Concerning economic integration in East Asia as well, Japan can never take the initiative in addressing 21st century issues if it has trouble dealing with 20th century-type trade of goods.

Japan should first, and as a minimum, declare that measures at national borders for agricultural products will be replaced by domestic subsidies within 10 years, though this is insufficient for fundamentally resolving the issue. This will expand options when participating in FTA negotiations, allowing Japan to significantly improve its negotiation stance. Realizing Japan’s participation in TPP negotiations will stimulate and accelerate economic integration in East Asia. There will be areas where Japan can contribute to the contents of measures implemented, both in the TPP and East Asian economic integration. Conversely, Japan’s status in the international community will decline even further and its future inevitably is doomed if issues carried over from the previous century prevent it from taking strategic action.

Translated from “Chiiki shugi ga umidasu 21 seiki-gata kokusaibugyo no dainamizumu,”Diplomacy (Gaiko), Vol.9 (September 2011), pp. 113-121. (Courtesy of Toshishuppan, Publishers)