USING MONETARY POLICY TO END STAGNATION

Subsequent to the outbreak of the global financial crisis symbolized by the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, the United States, Japan, and other Asian countries have all been recovering, each at its own speed. Even Europe has returned to growth, although the Greek debt crisis has slowed the pace of recovery there. Particularly compared with Britain, which is transitioning into the postindustrial age and has, accordingly, seen a long-term decline in industrial production, Japan’s recovery was quick. Germany also bounced back fast, though its upturn has recently lost momentum.

Japan’s real gross domestic product and real consumption bottomed out in the January-March 2009 quarter and have returned to growth. Statistics on Japanese employment do not yet show improvement, but workers are spending more time on the job, and eventually the longer working hours will lead to gains in the employment index. Corporate ordinary profits hit bottom in the first quarter of 2009 and moved back up to 70% of their peak level in the first quarter of 2010 year ending in March 2010 (data for all industries except finance and insurance).

Though Japan is in the midst of something close to a V-shaped recovery, one cannot say that all is well. As yet its economy has not regained as much ground as has the economy of the United States, the epicenter of the global financial earthquake. While Japan’s downturn was quite steep, its upturn started off on a gentle slope and now seems to be leveling off. The economy, it seems, is running out of steam.

The so-called BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, and China), meanwhile, have been doing remarkably well. In all of them except Russia, industrial production has now climbed above the peak prior to the global financial crisis. It seems that to China and India, the Lehman shock was no more than a little bee sting, an episode that has already faded into the past.

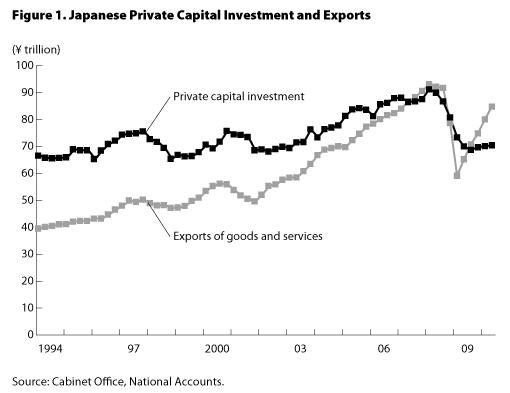

There can be no doubt that growth has resumed in Japan, but the degree of recovery has hardly been satisfactory. What are the background factors that have caused the pace of the upturn to be relatively slow? Figure 1 charts the trends in exports and private capital investment. In earlier recovery phases, an expansion in exports was linked to an expansion in capital investment. As soon as exports regained momentum, companies would invest in production facilities to meet the demand. Under the circumstances, nothing could have been done to prevent plummeting exports from causing a steep fall in corporate spending on plant and equipment when the global financial crisis struck. Now exports are again expanding briskly, but this time companies have been slow to resume their domestic capital investment. Apparently they are responding to the growth in export demand with production increases at their overseas bases, not at plants in Japan. This, we may presume, will be the pattern to be expected from now on.

Hesitating to Rely on External Demand

As a neighbor of the Asian countries that felt the world financial crisis to be a mere bee sting, Japan has been blessed with a good geographical position for becoming more deeply involved in Asian development. Moves in this direction are being blocked, however, by three interrelated factors. First, the Japanese have persuaded themselves that becoming reliant on overseas demand is not healthy. Second, the yen has appreciated greatly. And third, there is little understanding of how the Bank of Japan’s monetary policy is causing a strong yen.

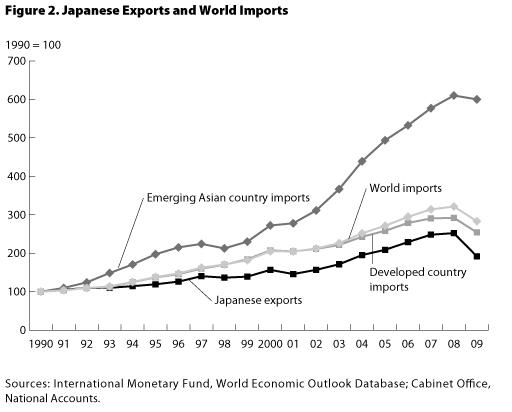

Many Japanese subscribe to the mistaken view that Japan’s growth has been led by external demand. The fact is that Japanese exports have not been expanding that vigorously. Figure 2 shows the trends in Japanese exports and world imports. As can be seen, the developing Asian region has been actively drawing in imports. Measured in terms of volume, the region’s imports registered 6.1-fold growth between 1990 and 2008. By comparison, the value of Japanese exports on a real GDP basis showed only a 2.5-fold expansion over this period. Japan’s development, in other words, has not taken full advantage of the demand in the Asian region. This probably comes as no surprise to people who have traveled around Asia. Whereas Japanese automobiles and household appliances were sweeping across the continent in 1990, recently the presence of the household appliances has greatly diminished, although Japanese cars remain highly visible.

Located as it is next door to the world’s most dynamically developing region, Japan should have been able to grow at a faster pace by making good use of the region’s development. Unfortunately, it was unable to do that. In fact, Japanese exports have not kept up even with the pace of import growth in the developed countries and in the overall world economy.

The high-flying yen is one of the primary causes of Japan’s loss of export vigor. Until now, an upturn in exports has served to trigger economic recovery, prompting the BOJ to stop implementing easy-money measures, at which point the yen would gain strength. This mechanism has been in consistent operation for quite some time, except during the period of so-called quantitative easing (March 2001 to March 2006) and when the Ministry of Finance intervened in the foreign exchange market.

When exports are on a roll, some people become uneasy. They fear that if the yen does not gain strength, problems could arise as a result of mounting black ink in the nation’s current account. This, though, is not something to worry about. When exports gain momentum, imports also increase. Though the graph does not show the changes in Japanese imports, they have been following a course that more or less matches the export trend. This is but to be expected. When a country engages in exports, it is sending things that might have been employed at home for use abroad, and it would become a poorer place if it did not at the same time bring in substitute goods from other countries. Those who make money from exports are sure to buy something else.

Over the long run, accordingly, black ink in the current account presents no problem. Inherently Japan ought to export that which it can produce efficiently and import that which it is poor at producing. An export expansion leads to growth in the economy’s well-performing parts and contraction in its inefficient industries, and Japan’s overall efficiency improves as a result.

Using Indirect Means in a Growth Strategy

While improving productivity is difficult, the surest means for accomplishing it is an export expansion. There are also other means available, but their effects are uncertain. Among them are selecting strategic industries to spearhead long-term development, developing new technology to pioneer new industries, and upgrading education to foster talents and elevate productivity.

I do not believe strategic industries can be successfully pinpointed. The industry the government is favoring with the largest budget allocations is agriculture, and Japanese agriculture is, needless to say, notably inefficient. The government’s record in upgrading professional education is also poor. Problems have arisen because more law schools than are needed were established. No doubt promoting graduate schools for other professions would have similar disappointing results. Neither selecting growth industries nor improving education to enhance productivity is something the government can accomplish. The Bank of Japan is initiating a system of extending funds to financial institutions engaged in fiscal investments and loans for growth sectors, but one must doubt that it will be successful at imitating the function of the Development Bank of Japan. As an organization that has not been able to accomplish its inherent task of vanquishing deflation, the BOJ is unlikely to do any better in a job outside its specialty.

Nobody knows how promising new industries can be brought into being. All that can be done is to avoid depriving successful individuals and enterprises of the just rewards of their efforts. This means, in short, reducing income and corporate taxes. To be sure, this is a very indirect way of promoting economic growth. A discussion is underway at present on cutting the corporate tax rate, and it is to be welcomed. I have my doubts, however, whether impatient politicians will be satisfied by growth-promoting measures that make no promise about when they will deliver results.

The BOJ’s Restrictive Policy

Compared with a growth strategy with indeterminate effects, stabilizing the value of the yen would produce quick results. Why has the yen become strong? The reason is a restrictive monetary policy. How can we say that policy has been tightened when interest rates remain so low? To answer this, we need to look at not interest rates but the money supply to see how much money is being fed into the economy.

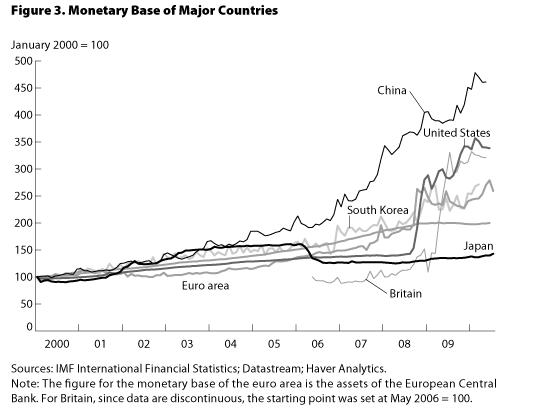

Japan’s bias toward restrictive monetary control was excessive even in the wake of the global financial crisis. Figure 3 shows the trends in major countries of the monetary base, narrowly defined money that central banks can supply. Note in particular the movements in and after 2007, when central bankers began to sense problems. The United States increased its monetary base by a factor of 2.5, the European Union by 1.6, Britain by 3.6, China by 1.6, and South Korea by 1.4. By contrast, there was only a tiny increase of about 10% in Japan’s monetary base.

The BOJ argues that other countries needed to expand the monetary base in order to absorb the shock to their financial systems from the emergence of vast quantities of bad debts, and that Japan had no such need because domestic banks were not burdened by a heavy load of nonperforming loans. It is true that bad debts did not hobble Japan’s banks. Nonetheless, the global recession dealt a sharp shock to external demand, and the rising yen delivered a follow-up blow.

As exchange rates are conversion ratios from one currency into another, restricting the supply of a currency will increase its value. Quite naturally the yen will gain strength when its supply is held down while the supply of other currencies is growing. Figure 4 shows the exchange rates of several major currencies to the US dollar. Since the start of 2007, while China’s yuan has held fairly steady, looking at the lows hit by other currencies, we find that the euro weakened by 16% against the dollar, Britain’s pound by 31%, and South Korea’s won by 41%. The yen, by contrast, has strengthened by almost 40%. Relative to the won, the yen’s power has doubled. A strong currency works to the disadvantage of exports. Without doubt the yen’s appreciation is largely responsible for Japan’s being hit harder than other countries by the financial crisis.

Perhaps Korea’s Samsung and Hyundai groups are performing superbly because their managers are more talented than the managers of Japan’s corporations. When external demand suddenly plummets as the result of a shock, however, companies in a country whose central bank opts not to give them a boost cannot hope to compete successfully against companies in a country whose central bank extends a helping hand. A doubling of the yen’s value against the won is like playing a game of soccer with the Koreans and giving them a double-sized goal to shoot at.

Using fiscal policy to generate demand means stepping up government spending, which has to be paid for by either issuing government bonds or hiking taxes. Both of these funding methods involve collecting money from the public. Basically the government just takes money out of citizens’ right pockets and puts it back in their left pockets. Monetary policy works in a different way. A central bank is capable of expanding the money supply without limit. It can, for instance, buy government bonds and supply the market with funds. These are not funds it collects from the public, and so it can put money in citizens’ left pockets without taking anything from their right pockets. Of course, adopting such a policy over an extended period of time would invite criticism, since it would trigger inflation and could wind up causing the kind of hyperinflation Zimbabwe has been suffering from. A policy of significantly expanding the money supply must therefore be left in place only for a while, after which the central bank must redirect its aim at a modest inflation rate of, say, 2%. This would be a policy of inflation targeting, and it provides one way of terminating more aggressive monetary relaxation.

Lessons from the Great Depression

The Bank of Japan stubbornly insists that monetary policy is powerless, that it is of little use in either increasing prices or expanding production. In the Great Depression of the 1930s, however, monetary policy had a dramatic impact. The countries that recovered most rapidly were those in which the central bank adopted easy money and acted to expand the money supply. Between the first quarter of 1933 and the third quarter of 1937, the broadly defined money supply (M2) in the United States increased 40.1%, and real gross national product grew by 53.7%.[1. Robert J. Gordon, The American Business Cycle (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986).]

When an elite group of monetary specialists in one country’s central bank pushes for a certain course of action, members of other elites may be persuaded to go along with it even if the argument is not buttressed with evidence. France’s political elite was in that position in the days of the Great Depression. The political elites in various other countries, such as Germany, Japan, the United States, and Britain, managed to avoid being distracted by what their central bankers were telling them to do. Hitler from the start placed no faith in what existing elite groups insisted on. Takahashi Korekiyo, who while a member of the political elite had a mind of his own, orchestrated Japan’s financial policy. He insisted on figuring things out for himself. As finance minister during the first half of the 1930s he was one of the first in the world to advocate monetary relaxation, and his policies rescued Japan from the depression. Unfortunately, his actions came to late. The Manchurian Incident of 1931 triggered fighting with China and started Japan off on its military adventurism, and most Japanese assumed it was this, not Takahashi’s guidance, that had ended the economic woes. President Franklin Roosevelt led the battle against the depression in the United States; he focused on Main Street, where ordinary Americans live, not on Wall Street, where the captains of finance hold sway. In Britain the depression drove the Labour Party out of power. Needless to say, British labor leaders were not receptive to the arguments of the monetary elite either.

By contrast, France’s political elite did miserably, and the nation trailed the rest of the world in recovering from the depression. What held it back was inflexible adherence to the gold standard and a refusal to loosen the monetary reins. Even as late as 1938 its production remained 25% below the level of 1929. As a result, the French people lost confidence, and social fissures widened. Germany recovered much more rapidly under Hitler. According to the Statistical Yearbook of the League of Nations, German industrial production doubled between 1933 and 1938. The whole nation united in a bid to overcome its humiliating defeat in World War I.

On May 10, 1940, Germany launched an attack on Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, and on June 14 its forces arrived in Paris. In only a little more than a month, the French capital had fallen. The conventional explanation for the French defeat is that the country was taken by surprise by the German use of a flanking route through Belgium that bypassed the main fortifications of the Maginot Line, but German forces had also moved through Belgium in World War I. Certainly the French were unprepared, but more than that must have been involved. After all, they also had tanks and fighters they could have deployed.

The real cause of the shameful defeat was the social divisions caused by prolonged economic stagnation. A divided people might have been able to dig in behind the Maginot Line to protect the country, but they lacked the mobility required for fighting with a combination of troops, tanks, and aircraft. In a mobile battle the laborers and farmers serving as troops under offices from the bourgeois class would have had to charge into dangerous situations, but because of the divisions among them, they were not willing to do that. Once the German forces were past the Maginot Line, the French lost the will to fight.

The French elite was unable to grasp that a radical monetary policy offered the best means of escaping from the depression. The continued implementation of misguided monetary management had opened up social rifts, and national power declined. If we adopt a different perspective, however, we can also see hope in the wretched experience of the French. In the postwar period France managed to achieve faster economic growth than Britain. Though the French had in essence been defeated while the British emerged as victors, French living standards overtook those of Britain after the war. Charles Kindleberger argues in World Economic Primacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996) that this came about because the defeat by Germany led to a replacement of the French elite. To be sure, Britain later moved out in front again as a result of such developments as the reforms of the Thatcher administration.

The BOJ’s Strange Arguments

Although Japan’s prewar elite had some outstanding members, notably Takahashi Korekiyo, these days everyone seems to have swallowed the nonsensical line of the BOJ. Monetary policy, the bank argues, is not involved in the ongoing deflation. It points instead to such factors as inexpensive imports from China and other low-wage countries, price markdowns due to streamlining in distribution and deregulation, a sustained wage decline, and a lowering of growth expectations. Deflation is structural factor, the BOJ says, and no amount of money supply expansion would bring it to a stop.

We need to note, however, that whereas China is exporting low-priced goods around the world, it is only in Japan that prices are falling. Distribution streamlining and deregulation may well cause prices to drop, but they should also be expected to speed up the economy’s growth rate, and that has not occurred. Wages are indeed in the midst of a downward trend, but that is because of the ongoing deflation and business slump, which have been caused by the BOJ’s passive policy stance. Companies are hardly likely to hike wages at a time of falling prices and slim profits. An expectation of slower growth in the future is a certainly a cause of diminished demand, since many people will tighten their purse strings, but that does not automatically make it a deflationary factor. Slower growth would also cause future supply to diminish, and that would be an inflationary factor. Supply and demand factors are both involved in price movements, and we would need to know which is larger before calling lowered expectations a deflationary force.

Of course, an expansionary monetary policy would pose problems of its own. Ultimately, monetary relaxation will cause interest rates to rise. Here we should note that interest rates are low today not because the BOJ has adopted a policy of easy money but because it is sticking to a policy that is fostering deflation. If the BOJ had acted in the same way the Bank of Korea did when it expanded the monetary base to deal with the global financial crisis, probably the yen would not have appreciated, exports would not have dropped so far, and employment would not have been cut back so sharply. Japanese production would have recovered in tandem with the recovery of the world economy, and prices would not have fallen. With output expanding, profits would have improved, and both real and nominal GDP would have increased. All this would have set the stage for expectations of an upturn, and short- and long-term interest rates would have risen. Higher interest rates would have increased the interest income of bank depositors, and older Japanese, who have large savings deposits, would have stepped up their spending.

To be sure, higher interest rates would push down the prices of long-term bonds, and banks holding large blocks of bonds would suffer losses. Ordinarily, though, banks should not be bothered by lower bond prices, since they derive the bulk of their profits from the differential between their lending interest rates and the interest rates they pay on funds they collect. They stand to profit from an upward trend in interest rates, and the gains should be larger than the losses from the fall of bond prices. Some banks may have portfolios that cause them to run into troubles, but that is not something for the government to worry about. Banks are in the business of seeking good clients to whom to provide financing; the work of investing in securities is something even ordinary individuals can do. The Japanese economy has no need for any bank that will lose more money from falling bond prices than gain money from rising interest rates. The economy will be better off if such banks close down.

Some people worry that higher interest rates will endanger public finance by driving up debt-servicing costs for the huge volume of outstanding government bonds, but in fact this is no cause for alarm. The force pushing interest rates up would be an economic recovery, and with business prosperous again, tax revenue would increase. The extra revenue would, moreover, be larger than the extra interest payments. One of the reasons the government went so deeply into debt in the first place was that low interest rates made this an attractive option. Though the government debt has been ballooning, annual interest payments have not risen. In fact, they have tended to decline on the whole. Under the circumstances, the fiscal authorities did not develop a sense of crisis. But rising interest rates will ring a warning bell and restrain moves to channel rising tax revenue into stepped-up government spending.

Advice for the DPJ Administration

Surely Japan will proceed down the road France took before World War II if the members of its political elite continue to buy the frivolous arguments of the monetary authorities. France found itself unable to overcome stagnation as a result of bungled monetary management, and it became a divided nation. The French people lost confidence in their own country’s elite, and they also lost the will to fight, as they were unable to forge a united front to repel an invader. The ramification of the country’s quick defeat rippled all the way into Asia, where it bolstered the position of Japan’s militaristic faction. If instead the warfare between France and Germany had bogged down in a stalemate, Japan might not have blundered off in the direction of reckless adventurism.

The people of Japan kicked the Liberal Democratic Party out of power last year because, as a result of the misguided monetary policy, the business slump just kept getting longer. Public discontent had mounted, and it became a major factor behind the victory of the Democratic Party of Japan in the August 2009 general election. I sincerely hope that the new administration will not be fooled by the strange measures the BOJ is devising, such as its new system for playing the role of the Development Bank of Japan. Recognizing that monetary policy does indeed have considerable power, the authorities must use it to extricate Japan from its quagmire.

Translated from an original article in Japanese written for Japan Echo Web. [August 2010]