Abenomics at a Watershed ―Proper Approach to Monetary Policy

Komine Takao, Professor, Graduate School of Regional Policy Design, Hosei University

One of the main topics people have discussed since the start of Prime Minister Abe’s second term in December 2012 is the government’s economic policy, which is commonly referred to as Abenomics. Nearly three and half years have passed since then, and now it seems that the initial form of Abenomics has been driven to take a major change in direction. In this paper, I will discuss Abenomics, focusing primarily on its monetary policy. This particular area has been forced to take a different turn because the limitations of the policy’s stance in the past are now apparent.

Abenomics is beginning to lose touch with its goals

It is easier to assess Abenomics by dividing it into two periods. The first period runs from the inauguration of the first Cabinet of Prime Minister Abe to March 2014, a period during which the economy remained relatively steady. The second period runs from April 2014, the time at which the economy came to a temporary standstill.

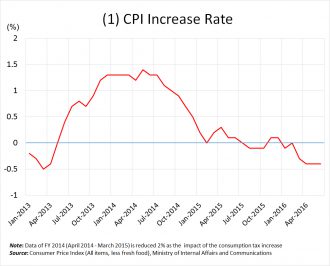

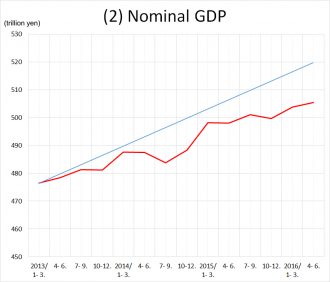

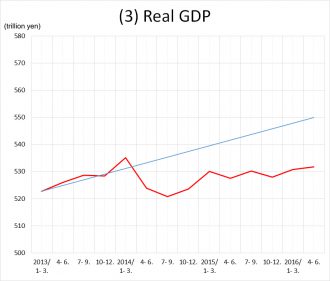

First, I will use certain economic indicators to confirm a few things about these periods. There are three major economic goals that Abenomics aims to achieve: a 2% rate of increase in consumer prices, a 3% nominal growth rate, and a 2% real growth rate. The 2% rate of increase in consumer prices and other goals were clearly specified in the joint statement the government and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) jointly announced in January 2013 immediately after the inauguration of the Abe Cabinet. The targets of the 3% nominal growth rate and the 2% real growth rate were presented in the growth strategy laid out in June 2013 (the official name is “Japan Revitalization Strategy—Japan is Back”), which stated that Japan aimed to secure an average annual economic growth rate of around a nominal 3% or a real 2% over the next ten years.

Last year “three new arrows” were launched, and stated that the Japanese economy aims to increase nominal GDP to 600 trillion yen by fiscal 2020. However, this is nearly the same as the 3% nominal growth because according to the “economic recovery scenario” in the projections released by the Cabinet Office in July 2016 (“Economic and Fiscal Projections for Medium to Long Term Analysis”), the nominal GDP will rise to nearly 600 trillion yen (more precisely 583 trillion yen) by fiscal 2020 if the economy continues to grow at an annual rate of about 3% in the upcoming years.

The first item (1) in Figure 1 provides a comparison between changes in the rate of increase in consumer prices and the 2% target. Although consumer prices moved out of negative territory and leveled off at the 2% level by the first half of 2014, in the second half of the year they began to deviate from the target and head towards the lower side. As of the time of writing, they have nearly returned to the level they were at when Abenomics began.

Items (2) and (3) provide a comparison between the expected value of GDP and the actual GDP in the event that the economy grows at a nominal rate of 3% and a real rate of 2%. Although GDP moved close to the target value up until early 2014 in both cases, over time it also began to deviate from the target and head towards the lower side.

The economic policy of Abenomics largely delivered the intended results in the first period, but the actual economy began to deviate from the target in the second period, suggesting that the limitations of Abenomics had come to the surface.

Emerging limitations and adverse effects of the so-called different dimension monetary easing

So, why has such a difference emerged between the first period and the second? In my opinion, it is because the economic effects that emerged in the first period represent an essentially short-term phenomenon that has not only disappeared, but has even had an adverse effect on the second period. This was particularly noticeable in Japan’s monetary policy.

Monetary policy in Abenomics has generally proceeded along the following course. First, as mentioned previously, an inflation target calling for a 2% increase in consumer prices was clearly specified in the joint statement in January 2013 immediately after the inauguration of the first Abe Cabinet. Next, the so-called different dimension monetary easing was launched under the auspices of Kuroda Haruhiko, the new governor of the BOJ, in April that year. Under this form of monetary easing, the BOJ intended to implement a monetary policy of a different dimension both quantitatively and qualitatively by (1) doubling the monetary base and the amount of the long-term government bonds and exchange traded fund (ETF) holdings of the BOJ in two years, and (2) extending the average remaining life of long-term government bonds to be purchased by the bank by more than double to (3) achieve the 2% consumer price target as soon as possible in a roughly two-year period.

Given that it became difficult to achieve the 2% target, the BOJ implemented additional monetary easing measures, such as increasing the purchase amount of bonds to about 8 to 12 trillion yen every month in October 2014. Because consumer prices failed to reach 2% even with these measures, at the end of January 2016 the BOJ began adopting the so-called negative interest rate policy of imposing a negative interest rate on some of the current accounts of banks at the BOJ.

As described earlier, this monetary policy produced great results during the first period of Abenomics. Unfortunately, these positive effects faded away in the second period, and ultimately resulted in a counteraction. The reasons for this development are as follows.

First, the limitations of the BOJ’s surprise policy method of moving the market by announcing an unexpected bold policy came to the surface. The initial impact of Abenomics came from an announcement. When the second Abe Administration began in December 2012, the yen exchange rate fell and stock prices rose, even though the Cabinet had yet to announce any policy. The market expected that once Prime Minister Abe came to power, the monetary policy would be eased significantly and the growth-oriented economic policy would be adopted.

This trend of weaker yen and rising stock prices gained additional momentum following the implementation of the strong “different dimension” monetary policy by newly appointed Governor Kuroda. Because this monetary policy was larger than many market players expected, the market was completely surprised and led it to drastically change its conventional views. This appeared to add extra momentum to the trend of the weaker yen and rising stock prices. Likewise, because additional large-scale monetary easing was implemented in October 2014 at a time the market did not expect, it once again reacted to this surprise, causing the value of the yen to fall. For this surprise policy method to succeed, the BOJ needs to send out an ongoing series of surprises that are highly praised by the market. However, while the negative interest rate policy launched in January 2016 surprised the market, it failed to earn its favor and in contrast appears to have strengthened deflation-minded sentiment.

What stuck out in my mind at that time was a comment about negative interest rates made in the Economy Watchers Survey (February 2016) conducted by the Cabinet Office. One general retailer said “Elderly customers keep a tight hold on their wallets because they heard something on TV or in the newspaper about the adverse effect of negative interest rates. Many customers think that the idea of negative interest rates means that the money they have will decrease without them even realizing. I feel it’s quite possible that we’ll see an atmosphere in which people are trying to spend as little as possible.” As this comment reveals, negative interest rates do seem to have heightened people’s anxiety about the future because many believe that negative interest rates will cause their savings to shrink. It also shows that people feel that if the economic situation of Japan is so bad that it requires a policy they’ve never heard of, then that policy is not worth taking.

Secondly, the method of emphasizing the strong motivation of the authorities by making a strong commitment has also reached its limit. With the “different dimension” monetary easing implemented in April 2013, the BOJ made a firm commitment about the period for achieving the target. At the Monetary Policy Meeting, the central bank set the goal of “achieving the 2% target for consumer prices as soon as possible within a roughly two-year period.” Speaking at a press conference held around that time, Governor Kuroda said that the BOJ would not hesitate to make adjustments if they were needed, taking into account the given situation, because the economy and finance are living creatures. This commitment of “2% in two years” and “not hesitating to make adjustments when necessary” gave the impression that the BOJ was really prepared, and was extremely effective in producing the announcement effect described earlier. This commitment was continuously reiterated and became a kind of policy mantra of the BOJ. While it is not uncommon for a central bank to set an inflation target, it is unusual to specify a precise time period for achieving that target. In addition, a statement such as “not hesitating to make adjustments when necessary” is basically the same as making a promise to take additional easing measures if achieving the 2% target in two years proves difficult. There is no problem making this pledge as long as the economy is working well, but if the economy fails to move as intended, it could end up holding the BOJ back.

After that, the rate of increase in prices partially deviated from this 2% target because of the effects of unexpected circumstances, such as falling oil prices. The additional monetary easing in October 2014 also failed to produce the expected results, and in the end the BOJ was unable to achieve its target of “2% in two years.” However, because the BOJ did not abandon its target of achieving “2% as soon as possible” and implementing “additional monetary easing without hesitation,” the market came to expect an ongoing series of new easing steps. It can be argued that the negative interest rate policy adopted in January 2016 was a measure made up by the BOJ. It knew this policy was incredibly reckless, and realized that it was tied down by the framework the bank had set up on its own.

Thirdly, while the weaker yen initially generated a favorable turn of the economy, the limitations of this approach gradually became evident.

Here I will provide a brief summary of what the weaker yen brought about in the first period of Abenomics. Looking at each fiscal year, the yen-to-dollar exchange rate fell about 17% from 83 yen in fiscal 2012 to 100 yen in fiscal 2013. Import prices in yen rose substantially by 14%. This rise in import prices pushed up prices, and the rate of increase in consumer prices (general, excluding fresh food) turned positive from negative 0.2% in fiscal 2012 to 0.8% in fiscal 2013.

As for export prices, Japanese companies were faced with two options: increase the export volume by lowering sales prices in foreign currencies, or increase the sales amount in yen (raise export prices in yen) by keeping sales prices in foreign currencies the same. Japanese companies selected the latter. This choice was reflected by the fact that export prices in contract currency terms declined only 1% in fiscal 2013, while export prices in yen rose by 10%. As a result, the revenues of companies in the manufacturing industry increased significantly (ordinary income in the manufacturing industry increased 38% in fiscal 2013 according to the Financial Statements Statistics of Corporations by Industry of the Ministry of Finance). This rise in prices and improved corporate earnings also had an impact on stock prices, which in turn rose.

The depreciation of the yen caused economic performance to improve dramatically during the first period of Abenomics. However, after the second period it gradually became apparent that the effects of the weaker yen would not lead to sustainable growth for the two following reasons.

First, the rise in prices and improvement in corporate earnings as a result of the weaker yen only come to the surface only when the yen depreciates. To sustain this effect, the value of the yen must continue to fall, but this is impossible. The positive impact the weaker yen has on economic performance is essentially a short-term phenomenon.

Second, companies did not use these higher earnings to expand the scale of their businesses, which in turn cut short the mechanism for economic expansion. In the second period of Abenomics, one thing that has been frequently pointed out is that although the value of the yen fell, capital expenditures did not increase, and wages failed to rise while corporate earnings expanded, the volume of exports ultimately failed to increase. The export volume increased only 1% in fiscal 2013, but this was because companies did not lower sales prices. Companies were also aware that the improvement in corporate earnings did not stem from their own raw potential, but rather that it was a short-term event. In addition, the reason why companies did not try to boost the export volume by lowering sales prices was that they recognized that it was not the time to export products by manufacturing them in Japan, but instead the time to increase local production close to areas where products are consumed. Thus, even though their earnings increased, they did not boost their capacity in Japan or raise wages.

Change in direction required for Abenomics

I have discussed the limitations of Abenomics mainly from the standpoint of its financial policy. While there is not enough space for sufficient discussion in this article, the same things could be said about fiscal policy. Abenomics had a positive impact in the first period, but in the end ran out of steam and failed to strengthen the basis for growth in the second period.

During the first period of Abenomics, public fixed capital formation (which is largely the same as public investment) increased 10.3% in fiscal 2013, and the direct effect of this alone drove up the real GDP growth rate in fiscal 2013 by 0.5%. However, public fixed capital formation declined 2.6% in fiscal 2014 and then 2.7% in fiscal 2015, effectively dragging down growth. Public investment has a positive impact on growth only when it is increasing. In other words, the government must continue to increase public investment every year so that it can drive up the growth rate. This is something that is completely impossible for Japan given the strained state of its public finances.

In short, the effects of both the monetary and the fiscal policies of conventional Abenomics have largely disappeared. However, Prime Minister Abe indicated that he intended to “accelerate the pace of Abenomics” after his ruling coalition scored a major victory in the Upper House elections in July 2016. If this means that he intends to further promote present monetary and fiscal policies, it would be risky for the following reasons. We will take a look at these reasons, using the monetary policy once again as a point of reference.

The first reason is that if the government tries to continue moving forward the monetary policy while maintaining a strong commitment as described earlier, it will have no choice but to implement extraordinary policies that are rather far-fetched. The unconventional policy of negative interest rates has already been implemented, and even “helicopter money” is now being discussed. There are several definitions of the helicopter money, but the main point here is that the BOJ underwrites government bonds issued by the government. As a result, the government is not liable for its debts.

Many financial experts have a positive view of negative interest rates, seeing them as a potent tool for monetary easing. On the other hand, there seem to be few experts who actively support helicopter money because of concerns about an increase in the national burden due to factors such as the decline in profits payment by the BOJ and hyper-inflation, etc.

To me, both negative interest rates and helicopter money are extremely unnatural policies because they run counter to what we call the “providence of the economy.” When we take a straightforward look at negative interest rates, the idea essentially implies that if we deposit money, that money will decrease, while if we borrow, the money we have will increase. If this kind of negative interest rate truly occurs, it will bring about an inconceivable economy in which people no longer deposit money in banks but instead go on borrowing money that will never be used. Also, if the government spending can be covered by helicopter money without any form of obligation, the government will no longer need to levy taxes. If such a sweet deal existed, every country in the world would have already implemented it by now.

The reason why the Japanese government is pursuing such far-fetched policies is that it feels bound to honor its commitment of achieving the “2% target as soon as possible” and “not hesitating to implement additional monetary easing.” The government should allow itself greater flexibility in this commitment. Because the economy is influenced by many factors, such as conditions overseas and technological innovations, it is not possible to realize the ideal economy through government policies alone. In regards to prices, the government needs to avoid commitments that specify a time frame, such as “two-year period” and “as soon as possible.” It should view target prices as a kind of a guide, and position them as the desirable level the government should aim to achieve over the long term.

Second, the government should change its stance of policy approach from a short-term “emergency response” to a long-term “structural reform.” The extraordinary fiscal and monetary policies implemented by Abenomics can only be rationalized in the case of an emergency that cannot be addressed by ordinary policies.

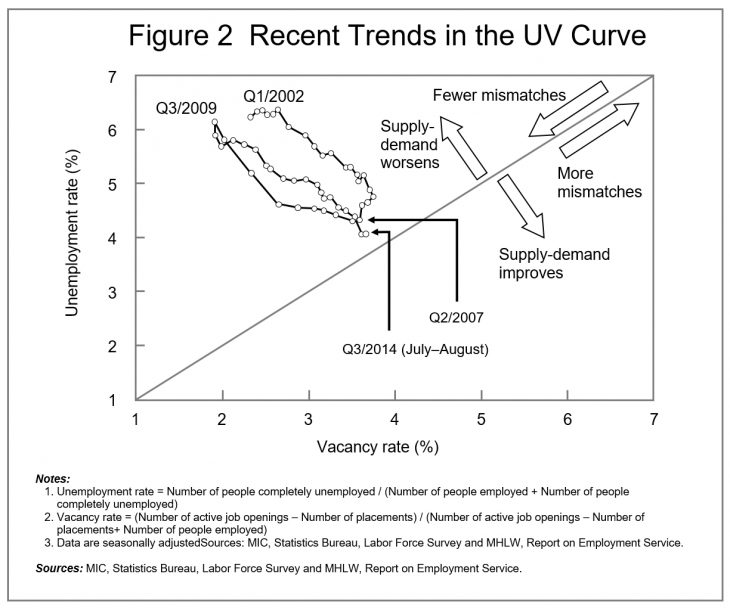

If someone were to ask me if I felt we faced an emergency now, I would say “no.” Take the employment situation, for example. Figure 2 shows a chart called the UV-curve, which plots the actual figures for the unemployment rate on the vertical axis and the job vacancy rate on the horizontal axis. The labor demand matches up with the labor supply on the 45-degree line in this chart, and unemployment that exists at that time can be regarded as structural due to the mismatch of demand and supply, instead of the result of the lack of demand.

As you can see in Figure 2, the curve went above the 45-degree line at the beginning of 2016. This means that even if the economy is stimulated further, it will still be difficult to improve the employment situation. In other words, we are now at a level that is close to full employment. Looking at this, it is difficult to say that the current Japanese economy faces a crisis that requires the government to implement extraordinary policies.

The decision was made in July 2016 to implement additional monetary easing measures. However, what is needed now is not forcibly stimulating the economy by boosting demand, but instead strengthening growth power from the long-term perspective. Going forward, I believe that the government should work on structural issues, such as deregulation, reforms in the way people work, and social security reform to raise the productivity of the Japanese economy as a whole and develop its basic growth power.

Translated from “Tokushu: Hakuhyo no Sekai Keizai / Tenki no Abenomikusu — Tadashii Kinyu-seisaku no Arikata (Special Feature: World Economy Walking on Thin Ice / Abenomics at a Watershed―Proper Approach to Monetary Policy),” Chuokoron, September 2016, pp. 90–97. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [September 2016]