A New Perspective on Measures for the Declining Birthrate: Provide Better Benefits in Kind Instead of Benefits in Cash ― The imminent challenge of expanding child care services

< Key Points >

- Create positive effects of female employment on fertility rates

- Rapid increase in benefits in cash does not directly lead to the reverse trend of fertility rates

- Other countries that show higher fertility rates shifted to benefits in kind after the 1990s

Oshio Takashi, Professor, Hitotsubashi University

Japan’s total fertility rate (average births per woman during her lifetime) was 1.45 in 2015, which seems to show a tendency toward recovery. Some advanced countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom and France, show fertility rates greater than 1.8. The pressure of the declining birthrate and aging population that currently faces the Japanese economy and society is not seen in other advanced countries as a common phenomenon.

Child-rearing support as a measure for the declining birthrate consists of benefits in cash, such as child allowance, and benefits in kind, such as child care services. The scale of Japan’s child-rearing support is significantly lower from an international perspective. The author is of the opinion that given the experience of the advanced countries that showing higher fertility rates, child-rearing support should be significantly expanded with a particular focus on benefits in kind.

The Plan to Realize the Dynamic Engagement of All Citizens promoted by the Abe administration aims to achieve a fertility rate of 1.8. With a focus on this, the author will introduce a brief comparison between the differences in fertility rates and child-rearing support between eight advanced countries whose total fertility rates were over 1.8 in 2014 (other countries that show higher fertility rates), including the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Japan.

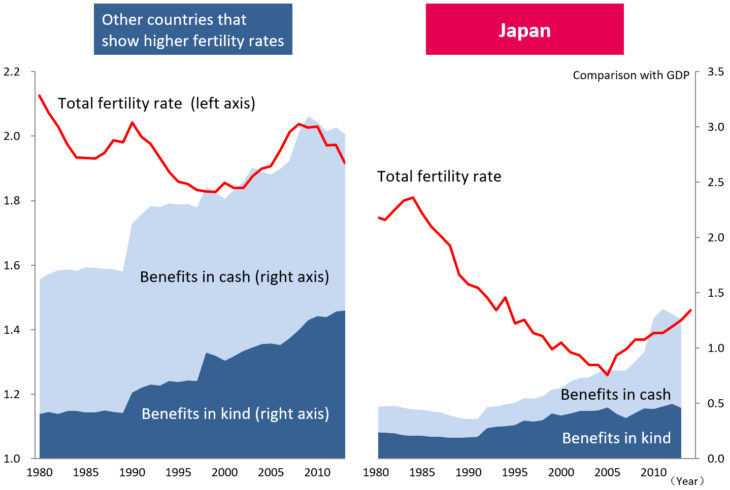

Other countries that show higher fertility rates, Japanese fertility rates and measures for child-rearing

Note: For other countries that show higher fertility rates, simple averages of eight advanced countries whose total fertility rates were greater than 1.8 in 2014 (France, Ireland, Iceland, New Zealand, Sweden, the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia). Benefits in cash and benefits in kind for child-rearing support (comparison with GDP) are based on the family-related social expenditure published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Source: Compiled by the author based on data published by the OECD.

The first thing that can be confirmed from the figure shown above is that the decline of fertility rates is slowing in not only Japan but also in other countries that show higher fertility rates. Of course, different countries show different trends, but fertility rates bottomed out in the late 1990s on average. In recent years, fertility rates have peaked due to the impact of the economic downturn after the international financial crisis of 2008. In spite of this, the declining birthrates are slowing. However, note that the margin of the decline in fertility rates after the 1980s was smaller in other countries that show higher fertility rates than in Japan.

On the other hand, fertility rates reversed in Japan as well, but the period in which fertility rates reached a low-point was later than in other countries that show higher fertility rates and the standards were also significantly low. What caused these gaps? There is no significant difference in female working environments. The employment rate of women between the ages of 15 and 64 in 2013 was 67% on average in other countries that show higher fertility rates whereas the rate was just 62% in Japan. This alone cannot explain the gaps in the fertility rates. The wage gaps between men and women are not an issue limited to Japan.

Female employment has both positive and negative impacts on fertility rates. Female employment is a positive factor in that it increases income, but female employment could be a negative factor if childbirth and child-rearing deprive women of opportunities for employment and gaining income. It seems that you can make a significant explanation by claiming that the lower fertility rates in Japan have a larger negative impact than in other advanced countries.

Opportunity costs for childbirth and child-rearing are significantly influenced by how child-rearing support is implemented. The OECD defines the wide range of public services by governments as social expenditure and child-rearing support is categorized as family-related social expenditure. This consists of benefits in cash and benefits in kind. The above-mentioned figure shows the change in the ratio of these two types of child-rearing support compared to GDP with a focus on the trends of fertility rates.

The first thing that can be confirmed from this is how low the standards are for Japanese child-rearing support. It has shown an increasing trend in the last few years, but its ratio to GDP remained only 1.3%, even in 2013. In Japan, The rate was above Japan’s current level as of 1980, with 1.6% in other countries that show higher fertility rates and even 2.9% in 2013. During that period of time, female employment made progress in other countries that show higher fertility rates at the same pace as in Japan. Therefore, the straightforward interpretation that it was due to the effect of promoting fertility with child-rearing support was larger than the effect of curbing fertility by childbirth and child-rearing and that the fertility rates in other countries that show higher fertility rates did not decline as much as in Japan.

Next the author will look at the large gaps in the contents of child-rearing support and their changes between Japan and other countries that show higher fertility rates. In Japan, family-related social expenditure rapidly increased after 2010 and a significant part of this can be explained by the increase in benefits in cash. This is because the child allowance was introduced in 2010 and cash-based assistance for child-rearing support has been expanded in the form of child-care allowance since that time. But because fertility rates reached their lowest point in 2005, it is unthinkable that the rapid increase in benefits in cash, such as child allowance, triggered it.

Other countries that show higher fertility rates have also implemented benefits in cash for many years that are significantly larger than the level in Japan. Note that there is a significant shift from benefits in cash to benefits in kind on the focus of child-rearing support after the early 1990s. As demonstrated by the figure mentioned above, a significant part of the expansion of the scope of child-rearing support in the last thirty years in other countries that show higher fertility rates can be explained by the increase in benefits in kind.

I have no choice but to closely examine the policy effects on other occasions, but it seems that the slowed decline of fertility rates in the late 1990s in other countries that show higher fertility rates can be explained by an earlier shift to benefits in kind for child-rearing support. Benefits in kind have gradually improved in Japan as well and it is conceivable that this has an impact on the reverse trend of fertility rates.

Countries that show higher female employment rates tend to show higher fertility rates after the 2000s. Based on this fact, some argued that an increase in female employment leads to an increase in fertility rates. But it is unscientific to argue that such causality equals correlation from observations at the same point in time. In fact, Japanese experience shows that the increase in female employment rates and the decrease in fertility rates occurred simultaneously, until fertility rates reached the lowest point in 2005.

Meanwhile, however, it is also unscientific to deny the correlation between female employment and fertility rates from the beginning. If female employment rates rise, stronger social calls for the government to provide child-rearing support will occur. It is very likely that fertility rates will recover with the government’s expansion of child-rearing support in response to such calls. The question is whether this pattern will come true or not.

If you look at the specific data of advanced countries, you will discover that benefits in cash have a positive correlation with female employment rates but this relationship is not very close. Benefits in kind are more interesting. If female employment rates remain low, benefits in kind also remain low. But if female employment rates rise to a certain level, benefits in kind tend to increase. In other words, if female employment rates increase sufficiently, it will lead to the expansion of benefits in kind and the reduction of opportunity costs for childbirth and child-rearing, which will yield the positive effect of gaining income through female employment with the slowed trend of declining birthrates.

From the above figure, you can confirm the shift of focus to benefits in kind in other countries that show higher fertility rates and the subsequent reverse trend of fertility rates. It can be speculated that such a mechanism worked against the background.

For couples who consider childbirth and child-rearing at home and abroad, there is the urgent issue of who will care for their future children. In particular, dual-income couples will be unable to solve this issue even if they receive some child care allowance. It is conceivable that there will be many cases in which such couples decide to give birth to and raise children only when child care services are readily available. The provision of child care services is more important than benefits in cash for couples to reconcile the discrepancies between work and childbirth and child-rearing.

In recent years, there have been stronger calls to address waiting lists for enrollment in nursery schools and under these circumstances, child-rearing support is a priority issue for the government to tackle. This means that the increase in female employment and the social changes created by it have entered a stage that strongly calls for the expansion of child-rearing support in Japan as well. The situation in Japan is not significantly different from other countries that show higher fertility rates in this respect.

Other countries that show higher fertility rates successfully promoted system reforms in response to such requests and maintained high fertility rates. Why not Japan? If Japan aims to recover its fertility rate, it can learn important lessons from the experiences of other countries that show higher fertility rates. It is necessary to secure a sustainable increase in the fertility rate by significantly boosting child-rearing support based on benefits in kind, including the expansion of child care services.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 7 February 2017 under the title, “Shoshika taisaku ni aratana shiten (1): Genkin yori genbutsu-kyufu jujitsu wo (New perspective is being required for the countermeasures to the falling birthrate (1): Provide stronger in-kind benefits rather than cash benefit).” The Nikkei, 7 February 2017, p. 28. (Courtesy of the author)