Bringing The Truth Behind Inflation to the World ― Reading the State of the Global Economy from the Demographics of Japan, China and Singapore

Six years have passed since Defure no shotai (The Truth Behind Deflation) was published. Here, I expand upon the answers offered by the book — which highlighted the importance of population in predicting the future economic outlook — and apply them in analyzing the global economy.

In my book Defure no shotai (The Truth Behind Deflation), which was published in 2010, I pointed out that the root cause of the long-term stagnation in the Japanese economy was the decrease in the population size of the active working generation.

Motani Kosuke, Chief Senior Research Fellow, The Japan Research Institute

The productive working-age population of Japan (those aged between 15 and 64, including foreign residents) peaked in 1995 at around 87 million, and by 2012 had already declined by over 10 million; a decrease of more than 12%. This decrease was accompanied by a decline in the volume of demand for housing, cars, home appliances, many food products and various other products for which the active working generation are the principal customers. However, due to advances in the mechanization and automation of production, the quantity of these products being supplied does not decrease, regardless of however much the number of available workers may decrease. Many companies, too, mistook the structural decrease in the volume of demand due to the change in the country’s population structure to be a cyclic decline due to the economic recession, and neglected to take measures such as adjusting production volumes or shifting to cater to the elderly consumer market. The result of these failures was a fall in prices due to excess supply surplus to demand in these product areas. What happened was not deflation, as a monetary phenomenon in the world of finance, but rather a microeconomic price crash.

In tackling declines in consumer spending such as this that are caused by population-related factors, empty promises such as increasing productivity by way of technological innovation — let alone measures such as monetary easing — are ineffective. The conclusion of Defure no shotai was that the three effective strategies are (1) tapping into the demand of the ever-growing number of elderly people and transferring the profits generated by that market in order to raise wages for younger people; (2) encouraging women to work; and (3) increasing not the amount of immigration by foreign nationals, but rather the amount of in-country consumer spending by foreign tourists visiting Japan. This was met by a major outcry from reflation theorists, who advocate that deflation is a monetary phenomenon that can be overcome by monetary easing. However, as I am sure you are aware, the unprecedented “new-dimension” of monetary easing carried out over the last few years — just as it was asserted should be implemented by those same reflation theorists — has had no effect whatsoever in terms of expanding personal consumer spending. On the other hand, the three policy measures that I pointed out in my book are ultimately being implemented/advanced by Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s administration. In other words, reality has finally caught up with the content of the book.

Incidentally, the decline in the size of Japan’s productive working-age population that began during the latter half of the 1990s is also beginning to occur now, around twenty years later, in various countries throughout Southeast Asia and in Europe. Based on the lessons learned here in Japan, we can predict with a high degree of probability what is likely to happen in these world economies. I would like to illustrate this below.

Looking at Absolute Numbers of Elderly People

When we start talking about population, one thing that always crops up is a comparison of elderly population percentages (the proportion of a country’s total population that is accounted for by elderly people aged 65 or over). However, these figures can easily lead to misunderstandings. For the same increase in the percentage of elderly people in the population, both the consequences and the countermeasures that should be taken differ completely between the case in which the actual absolute number of elderly people is increasing, and the case in which the number of active working people is decreasing. Furthermore, in countries where the percentage of elderly people is low but the increase in the absolute number of elderly people is progressing rapidly — in contrast with countries where the percentage of elderly people is high but the absolute number of elderly people is not increasing much — there is a need to quicken the pace of the increase in the size of healthcare and welfare budgets. When discussing population, before looking at the percentage proportion of elderly people in the population, the simple technique of looking at increases and decreases in absolute population numbers by age group (more specifically, of dividing the total population into age groups by five-year increments and expressing the numbers of people in each age group in an easy-to-understand manner, such as by displaying them on a bar graph) is effective.

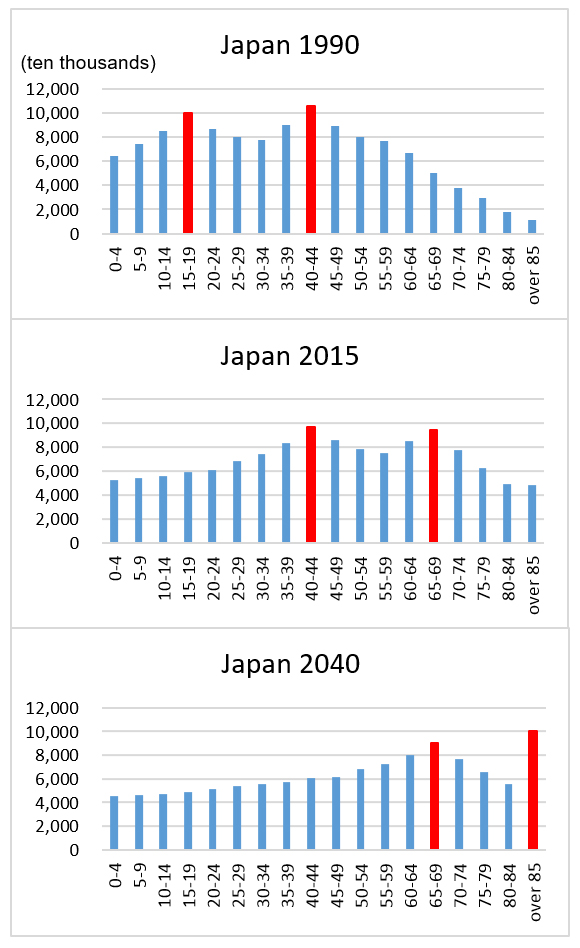

Let us take a look at the population structure of Japan in 1990, 2015 and 2040, based on data from the national population census and predictions by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (see figure on page 28). We can see clearly at a glance how the number of births and the number of people of productive working age are decreasing, and the number of elderly people is increasing. The aging of the baby boomer and junior baby boomer generations (which account for large numbers of people) is advancing as if in the manner of two large tsunami tidal waves. The state of population aging predicted for the year 2040 — when the baby boomer generation will exceed the age of 90 and junior baby boomers will exceed the age of 65 — is, in fact, already a reality in Japan’s depopulated areas. People living in the Greater Tokyo area today probably cannot imagine it. But it is precisely in this Greater Tokyo area, where over 40% of Japan’s junior baby boomer generation are concentrated, that this last rapid increase in the number of elderly people will take place in 2040.

We can draw the same kind of graph for foreign countries, too. Population estimates and predictions for the population of every country in the world between the years 1950 and 2100 (including the numbers of foreign nationals residing in those countries) can be downloaded, very conveniently, in Excel format from the UN Population Division website. Simply by plotting similar graphs for the years 1990, 2015 and 2040 and comparing them against the graph for Japan we can see that, to a greater or lesser extent, most other economically developed countries are following a similar path to Japan; experiencing decreases in the number of active working people and rapid increases in numbers of elderly people.

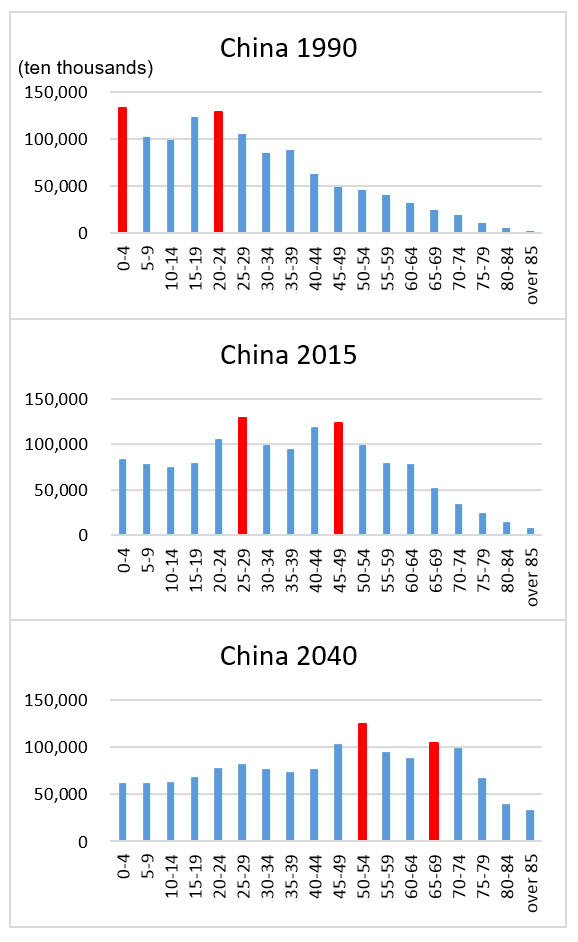

One country in particular that is exhibiting especially similar population changes to those seen in Japan is China. Like Japan, China has two peak generations, and is following a similar path to Japan almost twenty years later. This can surely be understood by a comparison of the graphs for Japan in 1990 and China in 2015.

In Japan in 1990, there are two peaks for numbers of people in their early 40s (the baby boomers) and late teens (the junior baby boomers). By comparison, the graph for China in 2015 also shows two peaks, for numbers of people in their late 40s (the generation created by the young people sent down to live in rural regions of the country as part of a policy implemented during the Chinese Cultural Revolution) and people in their late 20s (the children of that generation). The 25-year generation gap between the baby boomers and their children in Japan becomes a 20-year age gap in China, where people have a tendency to marry earlier. Nevertheless, the aging and transition of these population clusters into old age will inevitably lead to an unavoidable rapid increase in the number of elderly people and a decrease in the number of active workers in the country.

Some people may be under the misconception that the pace of population aging in China will slow due to the fact that China has recently abolished its one-child policy. This is a factual error that people often fall into when they look at population aging based solely on percentages of elderly people in the population.

Firstly, in China in the near future, a violent increase in the number of elderly people will take place due to the aging of the two peak generations just mentioned. This increase is completely unrelated to any increases or decreases in the number of children being born. The population of people in China aged 65 and over as of 2015 is 130 million, which happens to be almost the same as the total overall population of Japan at this time. However, by 2040, this figure will climb to 340 million; an increase in the number of elderly people that is both overwhelmingly large in scale both globally and historically, and also excessively rapid.

Secondly, the one-child policy was not enforced to such a thorough extent. Accordingly, the effects of abolishing the policy in terms of increasing the country’s birthrate will not be as great as we are often led to believe. The UN estimates represent the actual state of population figures, factoring “hidden children” into their calculations. In the figures for 2015, the number of children aged 14 or under is one for every four people of productive working age. If this 4:1 ratio is reworded in terms of municipalities in Japan, this is the standard for districts in which the birth rate exceeds 2. Incidentally, in Tokyo, where the birthrate is 1.1, this ratio is 6:1. Birthrate is tied more to the level of economic development than to political policy, and considering that birthrates in ethnically Chinese regions such as Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore (that became economically developed ahead of mainland China itself) are on a par with Tokyo across the board, regardless of the abolishment of the one-child policy, there is a high possibility that the number of children in China will actually decrease even further in the future. The UN predictions also tend towards that direction.

Twenty-five years down the line, in 2040, the productive working-age population of China will have fallen by 13%, from the current figure of 1 billion to just 870 million, and the percentage of elderly people in the population will have risen to 25%. This is remarkably similar to the changes in Japan’s population structure over the past twenty-five years. The failure of Chinese industry to correct the status-quo of excessive supply and the disposition to wage price wars (not even ruling out price crashes), is also similar to the situation seen in Japan. China therefore seems likely to experience the same “long-term deflation” that has occurred in Japan, the true identity of which will be the increasing severity of price crashes in numerous business domains over an extended period of many years due to excessive supply that is surplus to demand; in response to which the Chinese government will surely go on to implement misguided policies such as monetary easing and public investment, resulting in a worsening of government finances.

Immigrants Will Not Solve the Problem

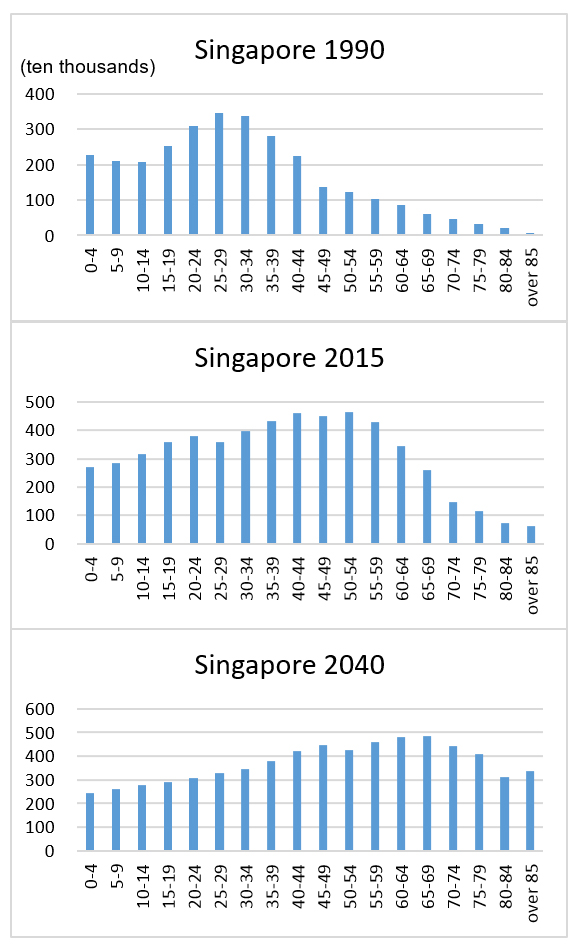

Can this kind of population maturity be prevented by introducing immigrants? Let us confirm the harsh reality by looking at the data for Singapore, a “country of immigrants” in which almost 40% of the resident population now consists of foreign nationals. During the twenty-five—year period between 1990 and 2015, the productive working-age population of Singapore has almost doubled, from 2.20 million to 4.08 million. With Singapore having an even lower birthrate than Japan, this increase has been due solely to an influx of foreigners. However, by 2040, also partially due to the aging of these foreign immigrants, we see a violent increase in the size of the elderly population, with the number of people aged 65 and over increasing to three times that of 2015, to 1.98 million; while on the other hand the

productive working-age population begins to decrease, dropping to 3.88 million. The combination of the acceleration in the dwindling number of children and the continual aging of the immigrant population, who exceed the age of 65 and stop working, eventually cancels out the beneficial effects of the influx of new immigrants.

The figures for Singapore indicate that introducing immigrants does not raise the birthrate. If immigrants assimilate the culture of the country to which they have emigrated, their birthrate, too, reaches the same level as the citizens of that country. If immigrants gather together and build an immigrant community, a zone in which they maintain their own native language and other culture from their native country then this may not apply. However, by creating such a situation, as seen in countries such as the USA and France, then separate social problems precisely like those seen in those countries will occur.

I have displayed population figures for Japan, China and Singapore, but in fact a similar phenomenon is taking place across the board in other countries in East and Southeast Asia where birthrates are low and life expectancy and economic development are also progressing to a greater or lesser extent. In South Korea and Taiwan, as in China, the declines in the productive working-age populations are just about to begin; and rapid decreases in numbers of children and increases in numbers of elderly people have already begun to occur. In Thailand, too, the size of the productive working-age population is soon expected to take a downward turn. Twenty years later the same situation will occur in Vietnam, and twenty years further ahead still the same thing will take place in Indonesia, with the situation progressing as a knock-on type scenario. It may seem that I am speaking of events far into the future, but in actual fact the pace at which the productive working-age populations of these countries are increasing is already dropping rapidly, and this is one factor contributing to the global economic slowdown.

In Europe, the decline in productive working-age populations has already begun, having peaked in 2010. The influx of immigrants and refugees from the overpopulated Middle Eastern and African nations was therefore unavoidable in some senses. However, their numbers are not great enough to reverse the direction of population change, and the scale and impact of side-effects in the form of friction over aspects such as religion are increasing year by year.

The only exception amidst all of this is the United States, where numbers of children are expected not to decrease even in the future. If this was thanks to immigrants then the same effects would be seen in Singapore, but as mentioned earlier this is not the case. The biggest reason is that the United States is a high-birthrate society to begin with, and there is a trend for the immigrants who flock there to also produce many children.

However, there are also pitfalls that await the United State. The first is the drop in pace of the increase in the productive working-age population due to the increase in the number of people aged 65 and over. Over the past twenty-five years the number of people of productive working age increased by 47 million, but over the next twenty-five years the increase is expected to stop short of 13 million. Companies will surely continue to overproduce, incorrectly guessing that the number of consumers will continue to increase at a similar pace to that seen thus far, and the country will probably face a similar state of “deflation” to that which we have seen in Japan. The second is the rapid increase in elderly people. During the past twenty-five years, the number of elderly people increased by 16 million, but in the next twenty-five years it is expected to increase by 34 million. In terms of the percentage of elderly people in the overall population, which was 15% in 2015, it is calculated that this figure will climb to 22% in 2040; a level not significantly different from that seen in Japan in 2010. For as long as there is no revision to its healthcare insurance system (which is said to be the most inefficient among all developed countries) and so on, we can expect social unrest and anxiety in the country to increase significantly in the future.

Population Decrease Signals Hope for the Future

In Southeast Asia and Europe, which together have a combined population of 2.3 billion, growth in productive working-age populations has already taken a downward turn. Even in North America, the momentum of the past is no longer what it once was. The true face of deflation, which was observed first in Japan, will surely soon become visibly apparent in other regions around the world.

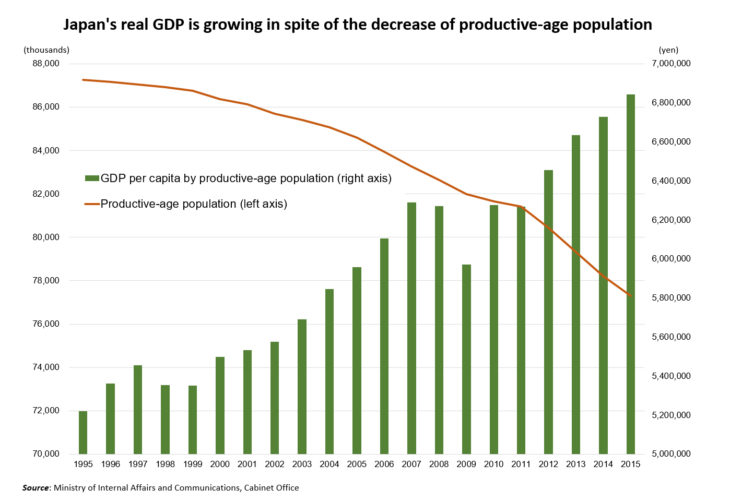

However, this does not necessarily mean that the global economy is in desperate state of hopelessness. Because a decrease in the number of people of productive working age leads to manpower shortages, despite a low rate of growth, Japan constantly has the lowest unemployment rates of any developed country. Furthermore, despite the fact that the productive working-age population has decreased by 12% over the last twenty years, Japan’s real GDP (Gross Domestic Product) has grown at a rate of 2–3%. By this calculation, GDP has grown by around 15–20% per person of productive working age in the population. There are many companies that are steadily generating profits while avoiding deflatory competition, by supplying products at relatively high prices that meet the specific demand of a certain group of comfortably living individual consumers in the market. The classic example is surely Starbucks. Even in the age of “deflation,” where we can drink coffee at convenience stores for a mere 100 yen, there are still no shortage of people who will buy expensive coffee. Conversely, there are industries such as the beer industry, where despite the fact that quantities of beer shipped are decreasing due to the population decrease, manufacturers are still decreasing overall sales turnover by selling low-malt beers and cheaper, third-generation beer-like alternatives.

Increasing sales turnover in regions where populations are growing is easy. Economists often say that the innovation displayed by the United States is amazing, but are they not perhaps mistaking automatic market growth due to population increase for the achievements of technological innovation? The companies displaying true innovation are those that are still steadily increasing their sales and generating profits in the Japanese market, where the population of people of productive working age is shrinking. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that we can tell whether or not a company will be able to survive in the global economy, with its dwindling pace of growth expansion, by looking at its performance in the Japanese marketplace.

Conversely, there are regions that have annual growth rates of 3%, but whose populations are increasing by 5% at a time. These regions show negative growth when viewed on a per-person basis. Because the overall market scale in these countries is expanding they make attractive targets for investment, but the citizens of these countries are impoverished and social unrest becomes increasingly pervasive. I wonder which is more desirable… areas like these, or countries like Japan which exhibit low growth but are more stable.

I would like us to seek ways of generating revenues in depopulated areas where population aging is already progressing ahead of the rest of the country, because the situation in these regions now reflects the situation that will occur in the Greater Tokyo area in the near future. For example, the productive working-age population in Shimane Prefecture began to decline ten years ahead of the rest of Japan overall. But despite the stoppage of overall growth, there are still companies there that are generating proper revenues. Unemployment levels in Shimane also consistently the lowest in the country. The shirt that I am wearing now was made by Gungendo, which has its main store in Iwami-Ginzan (Oda City, Shimane). The brand is increasing its fan base nationwide, with its business model of digging down into untapped consumer reserves by supplying small quantities of a wide range of emotionally fulfilling products at relatively high prices.

Population decrease is not something that should be viewed pessimistically. On the contrary, it actually represents hope for the future. The Earth cannot withstand endless population increase. The fact that populations in East Asia (including Japan) and Europe have begun to decrease naturally — not due to causes such as war or plague — will help to stave off food, water and energy shortages, and will expand the possibilities for the continued survival of humanity as a species. The decrease is also extremely slow. Given current numbers of births, the population of Japan will eventually decrease to around 70 million, but even so this would still be one of the largest populations in comparison with European countries, and would not mean that Japan would descend into being a small nation.

A 1% annual decrease in the size of the productive working-age population is offset by a roughly 1% annual increase in GDP per capita (i.e. per person). Devising innovative ways of tapping into the reserves of the portion of the country’s elderly people who are living comfortably and translating this into consumer spending is the true innovation needed to achieve this reality. If we translate “innovation” as “technological innovation,” then further interpret that in the limited sense of “technological innovation in manufacturing” and believe that we will somehow be able to make everything alright by simply refining our hi-tech technologies, then we are gravely mistaken. Innovation for the future is a battle that depends upon emotional and cultural capabilities.

Based on the latest developments in the demographics of Japan’ depopulated areas, we can also predict that the population decrease will eventually come to a halt. In many of Japan’s mountain villages and remote islands, absolute numbers of elderly people have already begun to take a downward turn. In some municipalities, where the decrease in the burden of healthcare and welfare services for elderly people is being redirected to taking in young people and offering childcare support, an upward turn towards an increase in the number of children can clearly be seen. It will be several decades before the same thing takes place in major metropolitan areas. But in the future, when the baby boomer and junior baby boomer generations are no longer with us, a nationwide trend of “population regeneration” — in which numbers of elderly people decline and numbers of children increase — will surely become apparent.

There has never been a time more important than now for thoroughly examining Japan, which leads the rest of the world in terms of population and economic trends, in order to predict the future of the global economy.

Translated from “Jinko de miru sekaikeizai: Defure no shotai wo sekaini ― Nihon, Chugoku, Shingaporu, Beikoku no jinkou dotai kara yomu sekaikeizi no yukue (The Global Economy, Viewed by Population: Bringing The Truth Behind Inflation to the World ― Reading the State of the Global Economy from the Demographics of Japan, China and Singapore),” Weekly Economist, October 4 2016, pp.27-31 (Courtesy of Mainichi Shimbunsha).