A Society Where People Can Work Even at Age 70

Despite concerns about Japan’s declining population, total employment reached a record 67.81 million in 2024.

Remarkably, 14% of employed persons are aged 65 or older, with 8% aged 70 or above. Workers aged 70 and over now number 5.4 million—nearly matching the 5.71 million aged 15-24. These older workers have become crucial in offsetting labor shortages and sustaining production. This demographic shift reveals that the traditional “working-age population” definition (15-64 years) no longer reflects Japan’s labor market reality, highlighting the need to redefine age boundaries in employment policy.

Photo: Takasu / photolibrary

“I haven’t thought about it specifically yet, but after working hard until I’m in my 60s, I’d like to retire completely and be free at the appropriate time. I’d like to spend my retirement years comfortably, focusing on the things I enjoy, such as following pop idols/ entertainment interests and hobbies, while also taking care of my health.”

For young people, this is likely the retirement future most people hope for. But is this future really possible?

Saving money is essential to achieving a comfortable life. The Public Opinion Survey on Household Financial Behavior (Central Council for Financial Services Information [now Japan Financial Literacy and Education Corporation [J-FLEC]]) looked at the financial assets of households with two or more people in their 40s. The survey found that, in 2003, over 60% of the households had assets exceeding 5 million yen. By 2023, however, this number has decreased by about half for people in their 40s, while the proportion of households with assets of less than 1 million yen will have increased significantly. Since many single-person households have no assets, the number of people with enough to prepare for retirement will be very small.

When assets are scarce, people want to work more and save their income. Thanks to the recent labor shortage, younger generations, such as those in their 20s, have seen greater wage increases than ever before. In contrast, there has been no significant improvement in wages for those in their 40s and 50s. The so-called employment ice-age generation[1] is at the heart of this sluggish wage growth.

Not only do they have low incomes, but rising prices mean they have no room for savings or other asset formation. Even if they wanted to save, interest rates are negligible, and they lack the capital to invest in stocks and the experience or wisdom to take risks.

In that case, social security, such as public pensions, will be their mainstay in the future. According to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare’s Pension Bureau’s “Public Opinion Survey on Life Planning and Pensions” (2023), over 40% of people aged 70 and older plan to rely entirely on public pensions when planning for retirement. This percentage decreases with each younger generation, reaching less than 20% for people in their 40s. Few young and middle-aged people believe that they will be secure in their retirement because of the pension system.

Naturally, the options for ensuring a stable life in old age are limited. The overwhelming majority view public pensions as the foundation of their retirement, supplemented by private pensions and savings. However, there is another realistic option.

Continue working within reason. In the aforementioned Pension Bureau survey, when asked, “Until what age would you like to work?” nearly 40% of people in their 40s and 50s said they would like to work until age 66 or older. Furthermore, nearly 20% said they would like to continue working until they are 71 or older.

While dreaming of retirement, the working generation—including the employment ice-age generation—is steadily looking to the future, keeping in mind the possibility of continuing to work.

Increasing older employment

Steady changes are already occurring in the employment situation for older people, as if anticipating the outlook of the younger generation.

While there are concerns about a declining population, the number of employed people in Japan as a whole actually reached 67.81 million in 2024, the highest number since statistics began (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Statistics Bureau “Labor Force Survey”). Of those employed, only 86% are in the working-age population between 15 and 64 years old. The remaining 14% are 65 or older, and 8% are 70 or older. Older workers have played an important role in preventing a slowdown in production activity due to labor shortages. The term “working-age population,” which refers only to those aged 15 to 64, is no longer in line with reality.

Needless to say, the increase in the number of older workers is driven by a growing elderly population. In addition, an equally important catalyst was legal reform.

Japan enacted the Act on the Stabilization of Employment for Elderly Persons, also known as the Elderly Persons Employment Stabilization Act, in 1971. Since then, it has been revised repeatedly in response to changing times and demands. The Amendment to the Elderly Persons Employment Stabilization Act, which took effect in 2013, had a direct impact on the recent increase in employment among people in their 60s.

With the implementation of this amendment, employers are now required to continue employing all employees who reach the age of 60 until they reach 65, if they wish to continue working. Specifically, the bill called for either the abolition of the mandatory retirement age, raising the mandatory retirement age to 65, or the introduction of a system of continued employment up to the age of 65 for all those who wished to continue working (although some transitional measures were permitted, this will become fully mandatory from April 2025).

This legal reform has had a significant impact on employment. The employment rate (the proportion of employed people in the population) for those aged 60-64 was 58% in 2012, but exceeded 70% in 2019, just before the spread of COVID-19, and has recently reached 74% in 2024. Considering that in 1998, when retirement under 60 was banned, the employment rate for people in their early 60s was just over 50%, it feels like a different era.

The impact of the 2013 legal reform extended beyond those in their early 60s. Even those aged 65–69, outside the legally mandated age range, have seen an increase in employment rates as the legal reform has paved the way for improving the employment environment for the elderly. The employment rate for those in their late 60s rose from 37% in 2012 to 48% in 2019 and is expected to reach 54% by 2024, meaning more than half of this population will be employed. While people in their 60s were once associated with retirement, it has become the norm in Japanese society for many people to continue working.

Additionally, the employment rate for those aged 70 and over has accelerated since 2017, five years after the legal revision. While the employment rate for this age group was around 13% in the early 2010s, it has been steadily increasing and is expected to reach 20% by 2024. Currently, the number of employed persons aged 70 and over is 5.40 million, which is close to surpassing the 5.71 million employed people aged 15-24.

When we think of people aged 70 and over who are employed, we tend to imagine those working in self-employment sectors such as agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and retail. Actually, only 1.81 million of the 5.4 million employed people are self-employed. A recent trend is that most people continue to work as employees even into old age.

Most Older Workers Remain Employed

It is not uncommon to see older people working in everyday life. People working in cleaning services and at construction sites. People directing traffic at construction sites. People patrolling as security guards. They transport goods, drive taxis, and drive to and from home care services.

At the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, people responsible for maintaining social infrastructure, such as ensuring cleanliness, hygiene, and safety, were referred to as “essential workers.” Often, these workers retire from their previous company or take on new roles after turning 65, following the end of their continued employment. When we think of people aged 70 and over who are employed, we may think of these workers as the majority. Nevertheless, an unexpected fact was discovered when the results of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Statistics Bureau’s “Employment Status Survey” (2022) were compiled. This survey is conducted every five years and surveys approximately one million people nationwide.

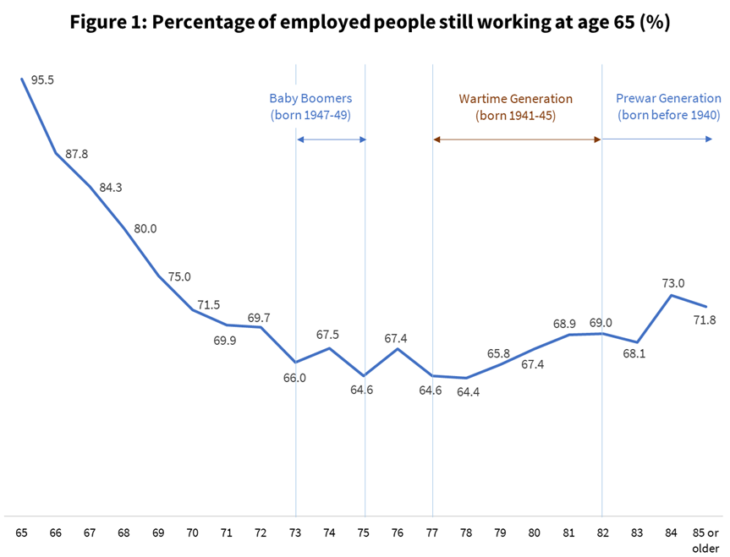

Figure 1 shows the continuing employment rate, which is defined as the percentage of people at each age who are still employed by the same company at age 65. Although 88% of employed individuals aged 66 were still in the same job a year ago, the continuing employment rate gradually decreases as people reach the upper age limit for continued employment or choose to change jobs or retire in their late 60s.

Note: The figures represent the percentage of employed persons at each age who have remained with the same employer they had at age 65.

Source: Special compilation by author of the “Employment Status Survey” (2022) conducted by the Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

The figure also shows that the decline in the continuing employment rate halts once employees reach the age of 70, stabilizing at a level in the mid- to late 60s. In other words, approximately two-thirds of employees aged 70 and over continue to work at the same company where they were working at age 65. Even when limited to “employees” aged 70 or older, it was discovered that the majority of these employees are still working in the jobs they were in at age 65.

Many employees aged 70 and over work part-time or in other short-term positions. Conversely, among those who continue to work at age 65 (hereafter referred to as “continuing employees”), a significant number are still working as regular employees even after turning 70. Many have worked for their company for over 20 years, and some continuing employees are “career-long employees” who have continued working since graduating from school.

Compared to those who start working at their current job after age 65 (hereafter, “new employees”), continuing employees are more likely to work in production sites such as construction and manufacturing. As “veteran skilled workers,” the skills they honed and mastered during their apprenticeship are still needed. Furthermore, many continuing employees have dedicated many years of experience as office workers at their company, and their experience is still valued. While self-made person craftsmen and the like are primarily male, many of the trusted, veteran office workers are women, so the ratio of men to women among those continuing to work is almost half and half.

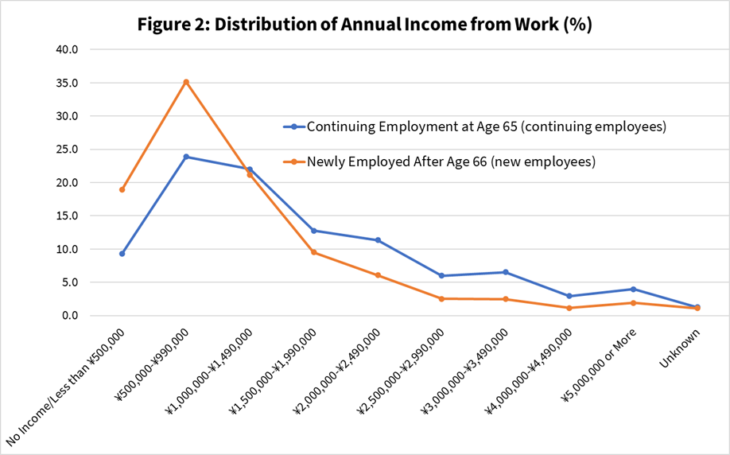

There are also differences in the income earned from work between new and continuing employees. Figure 2 shows the distribution of annual employee income from one’s ordinary job. For both continuing and new employees, the most common range is “500,000 to 990,000 yen.” For many, it is difficult to make ends meet on income from work alone. Thirty-five percent of all new employees fall into this income bracket. Just under 20% have “no income or less than 500,000 yen,” and more than half earn less than 1 million yen a year.

Note: The data covers employees aged 70 or older working in non-agricultural, forestry, and fisheries sectors.

Source: Special compilation by the author based on the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Statistics Bureau’s “Employment Status Survey” (2022)

On the other hand, compared to new employees, there is a smaller proportion of continuing employees with “no income/less than 500,000 yen” and “500,000 to 990,000 yen,” and the income distribution [for continuing employees] is positioned further to the right. The percentage of continuing employees with annual incomes exceeding 2 million yen is 31%, more than double the percentage of new employees. In the case of single-person or married couple households, people who earn enough income to live on are also included in the category of continuously employed.

For 53% of those new employees, their main source of income is pensions and annuities. In contrast, wages and salaries are the main source of income for those continuing to work at 68%. This indicates that continuing to work contributes to a more comfortable retirement.

Remnants of the Showa era[2]

Many people who are currently over 70 were in their prime working years between the 1960s and 1980s. Among most Japanese labor economists, it is commonly believed that the “Japanese employment system” or “Japanese employment practices” were established during this period. There are various hypotheses about the origins of the Japanese employment system, characterized by long-term employment and seniority-based wages, including the merchants of the early modern period, the prewar industrialization, the wartime-controlled economy, and the postwar reforms and rapid economic growth. And there is little disagreement with the view that its influence became widely established in Japanese society between the 1960s and 1980s.

The leading hypothesis explaining the development of the Japanese employment system is the “intellectual skills hypothesis,” which was developed by labor economics expert Kazuo Koike (1932–2019). This hypothesis posits that intellectual skills, or the skills and techniques developed through workplace experience and learning, enables employees to respond appropriately to the non-routine problems / unforeseen contingencies that frequently arise within companies. The workplace was designed with a meticulous system of skill development, including extensive job rotation and long-term competition among employees through performance appraisals and other individual evaluations. This system laid the foundation for lifetime employment and seniority-based wages, which guaranteed rewards for continued effort within the company.

According to the intellectual skills hypothesis, many current employees aged 70 or older developed their skills over long periods of time at the same company. In human capital theory, which is closely related to this hypothesis, skills based on unique experience within a company are called “firm-specific skills” because they are particularly productive in that workplace. In theory, firm-specific skills are a joint investment between employees and companies, with the benefits distributed between them according to bargaining power. Companies that have invested heavily in their employees prefer to continue employing them as long as they can expect to reap the rewards. Workers also prefer to stay with their employers rather than change jobs because continued employment allows them to reap the benefits of their skills.

In labor economics, the dual structure theory focuses on the division of the labor market into an internal labor market and an external labor market. In the internal labor market, a long-term relationship of trust has been established between labor and management. Information sharing has improved, enabling them to jointly address unforeseen circumstances, such as an economic downturn.

The formation of an internal labor market, such as the encouragement of “enterprise unions,” was also characteristic of the Japanese employment system. This makes it easier for companies to understand the skills and preferences of individual workers and avoid the mismatch between abilities and workplaces that can occur when hiring from an external labor market. Long-term employees have a good understanding of the company’s situation, which reduces the stress they experience when changing jobs.

In these circumstances, incentives for long-term employment are created for companies and employees alike. For older workers, there is a mechanism that makes it rational for them to continue working as long as there are benefits to skill development and information sharing. The current employment situation for people over 70 still strongly reflects the “remnants” of the traditional employment system established during the postwar Showa period.

Pension reform is difficult

Until the early 1990s, Japan’s traditional employment system was admired worldwide for its role in the country’s international competitiveness. The people who most certainly benefited from this were those born up to around the 1960s, who graduated from school and entered the workforce before the collapse of the bubble economy, when the Japanese economy was at its peak.

The generation that worked under the Japanese employment system has developed the company-specific skills mentioned above, and is more likely to avoid mismatches with companies. As a result, many people continue to work into their 70s.

The situation is very different for those who graduated after the bubble economy collapsed, forcing a review of the Japanese employment system. One example is the “employment ice age” generation, who graduated between the mid-1990s and early 2000s.

The employment ice-age generation earn lower wages than previous generations, even when compared to full-time workers of the same age. Their short tenure and lack of opportunities to develop skills over time within companies are directly linked to their current low wages. The government has announced that it will continue and expand support measures such as reskilling (relearning) to combat the employment ice-age. These measures will likely only result in wage increases for a small proportion of the employment ice-age generation.

If low wages are the result of a weakening of the Japanese employment system, then the effects will naturally extend to generations after the employment ice age. Low wages will be a problem, and so will the possibility of receiving smaller pensions in the future for those who have only short periods of enrollment in the Employees’ Pension Insurance.

Professor Ayako Kondo of the University of Tokyo, a labor economist, has predicted an increase in elderly poverty after the employment ice age and has proposed expanding support payments to compensate for low pensions or introducing a guaranteed minimum pension. These proposals are worthy of consideration, and at the same time, securing large-scale, sustainable financial resources is also essential to improving social security systems, including pension systems.

As the results of the 2025 Upper House election showed, however, increasing social insurance contributions, which would reduce take-home pay, is likely to provoke strong public resistance and opposition. Given the current situation in which many political parties are unanimously calling for a consumption tax cut, it would be impossible to improve social security simply by raising the consumption tax rate. Issuing government bonds and other measures to raise funds is not suitable for the operation of social security, which requires above all else to guarantee sustainability. One option would be to redistribute money from elderly people with high pensions to those with low pensions. Nevertheless, gaining consent from the entire population, including those who have paid insurance premiums in the hope of receiving future benefits, is no easy task.

While it is necessary to improve systems that provide relief to low-income individuals and households, low incomes affect entire generations beyond the employment ice age. Therefore, there is a broad need to improve the retirement environment, not just address poverty.

Improvement through legal reform

If this is the case, only one option remains: creating an environment in which anyone can continue working if they wish, to compensate for the lack of assets and low pensions that come with low incomes.

Currently, the Act on Stabilization of Employment of Elderly Persons, amended in 2021, requires employers to make efforts to secure employment measures until age 70, in addition to their obligation to employ employees until age 65. Employers are being asked to make efforts to continue employment for those who wish to work, such as raising the retirement age to 70, abolishing the mandatory retirement age system, and introducing a continued employment system. Additionally, options other than employment have been added, including concluding a continuous outsourcing contract and participating in social contribution projects implemented, commissioned, or funded by the employer.

The focus going forward will be on further legal reform to transform the current “best-effort obligation” into an “obligation.” Needless to say, the obligation to ensure employment opportunities is imposed on employers, and does not in any way force employees to work until age 70. Continuing employment is entirely at the discretion of the individual. Ensuring the right to work until age 70 for those who wish to continue working will not only dramatically increase the employment rate for those in their late 60s, but also potentially expand employment for those 70 or older. This will benefit older people in low-wage, non-regular employment in particular, as it provides greater stability.

Ideally, the revision would come into effect by the late 2030s. By then, those born in the 1970s, including the employment ice-age generation, will be 65 or older. When the mandatory requirement of employment until age 65 was introduced in 2013, Japan was in the midst of a serious, prolonged recession, and there were concerns that promoting employment for older people would take away employment opportunities for younger and middle-aged people. Due to the current chronic labor shortage caused by a declining youth population, cautious views regarding the revision are unlikely to be as widespread as they were in the early 21st century.

The future amendment will likely be discussed in conjunction with pension system reform, which would change the eligibility age for basic old-age pensions and employee’s old-age pensions from the current 65 to 70. There will likely be opposition to the mandatory employment requirement until age 70, citing the heavy burden it places on employers. Nevertheless, companies that significantly reduced hiring of young people bear responsibility for creating the employment ice age in the first place. It is also necessary to bring together policymakers, human resources personnel, labor union members, and researchers.

Creating an environment where people can work until age 70 would be the first step toward abolishing the mandatory retirement age, a relic from the era of a high-fertility society, and creating a society where everyone can choose how long they want to work in Japan. Just as barrier-free access has benefited many people, including those without disabilities, creating an environment where people in their 70s can work comfortably would bring more comfort and security to the work and lives of younger generations.

Anticipated future discussions will focus on creating an environment where people can continue working.

Translated from “70-sai demo Hataraku Shakai (A Society Where People Can Work Even at Age 70),” Sekai, October 2025, pp. 36–44. (Courtesy of Iwanami Shoten, Publishers) [January 2026]

[1] This generation refers to people who graduated from school and began searching for jobs in the late 1990s and early 2000s, after the collapse of the bubble economy. They were unable to find jobs they wanted due to the difficult job market. Often referred to as the “Lost Generation,” many of these individuals have taken on unstable or non-regular employment, and some still face economic and social difficulties today.

[2] From December 25, 1926 (Showa 1) to January 7, 1989 (Showa 64).

Keywords

- employment

- retirement

- assets

- pensions

- employment ice-age generation

- older workers

- continued employment