Blueprint for the Future of Social Welfare (II) : Limiting State Responsibility to the Guaranteed Minimum

Key Points

- Japan has lagged behind in terms of human investment because of excessively expanded social insurance.

- Low-income earners are disadvantaged in terms of the social insurance burden and benefits.

- Reforms are needed that require middle- and high-income earners to make self-help efforts.

Prof. Tanaka Hideaki

The government has published the “New Economic Policy Package”, and drafted the fiscal 2018 Budget including annual tax reforms, with human resource development as the central pillar. I do not object to this direction, but there has been little analysis and verification of problems in the existing system based on data and evidence. The burden will be forced on children who lack voting rights if the budget deficit increases to improve childcare and education. In this article, I will discuss the tasks and remedies for overcoming the declining birthrate and aging population.

Human capital investment is a common issue in advanced nations as income disparity increase and economic growth slows with the progress of globalization and the shift to a knowledge-based economy, unless support in the form of education and vocational training is provided for low-wage earners with unstable jobs.

The response to such problems varies. In Scandinavian countries, the government sector absorbs employment and promotes family-related measures and aggressive labor market programs such as vocational training. The U.K. government grants labor-based tax credits (tax benefits) to reduce poverty, reflecting a shift from dependence on welfare to employment promotion, often called “workfare”. These initiatives are not compensatory welfare services, such as pensions. They stress the supply side of growth. However, Bismarckian states based on social insurance, such as Germany, Japan and countries in Southern Europe, have lagged behind in their response, with the exception of the Netherlands.

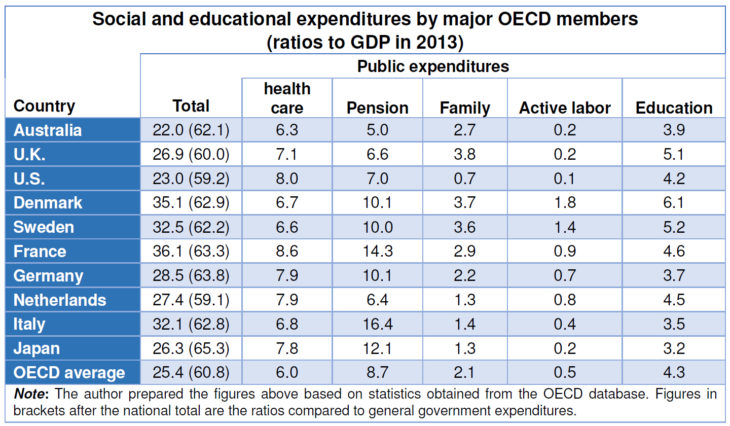

Looking at compensatory expenditures combining pension and unemployment insurance and social investment, including spending on family-related measures, active labor market programs and education, the ratio compared to gross domestic product (GDP) exceeds the average for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) members (about 10%), while the ratio of the latter compared to GDP is less than the OECD average (about 7%) in countries such as Germany and Japan. In Scandinavian countries, such ratios surpass the OECD average. The former ratio is less than the OECD average and the latter is greater than the OECD average in the U.K. and Australia.

In Bismarckian states, social insurance premiums have been easy to increase, while taxes have been difficult to raise and finance social investment. They have not been able to improve social investment partly due to the tradition of families caring for children. Social insurance assumes certain conditions, such as single male income and regular employment, and has fallen into a state of institutional fatigue. In particular, the rapid increase of irregular employees and gender-based discrimination are serious problems in Japan.

Japan has a big government in terms of social welfare, although the nation is aging. It surpasses Sweden in terms of pension and health care expenditures. (Refer to the table below.) Japan also outpaces Sweden in terms of net expenditures, taking into account social expenditures (total amount of social welfare excluding education) and tax treatment including credits and taxation of benefits.

Social expenditures rose by 3 percentage points in Sweden from 1980 to 2013, while it grew by 13 percentage points in Japan during the same period. Sweden restructured social security system through fiscal consolidation. Japan was not able to curb its growth. As a result, Japan surpasses Scandinavian nations in the ratio of total social and educational expenditures to general government expenditures. Is it possible for Japan, a country reluctant to tax hikes, to increase family-related and educational expenditures without increasing the budget deficit?

The observations above make Japan’s issues obvious—enhancing efficiency in fields such as pensions and health care, and allocating more of the budget for childcare, education and training.

The problems with pension and health care lie in the insurance system. Unlike income taxes, premiums are strongly regressive. The burden ratio of insurance premium to the total income falls as income rises. Monthly contributions of National Pension Plan are set at 16,490 per person regardless the level of income, in principle. Employees’ Pension Insurance contributions are flat rate, about 18 percent of the gross income, which is equally shared by employers and employees, however such contributions never increase after the monthly salary surpasses about 600,000 yen. Great many people such as self-employed and irregular works cannot contribute to National Pension Plan, thus the compliance rate for national pension contributions is 60% to 70% because of such regressiveness. The government has increased premiums over the past dozen years and the ratio of the total premium revenue to GDP rose from 8% in 1990 to 13% in 2015. The total premium revenue more than doubled compared to individual income tax revenue.

In theory, social insurance disciplines work because the benefits and burdens are balanced. However, social insurance in Japan is completely different, because contributions from employee insurance are transferred to the National Pension Plan and other insurance systems in order to support them financially, in addition to a large amount of general tax revenue which finances the shortage of contributions. Such transfers are for income redistribution, but the methods of this redistribution have been called into question.

Taxes invested in social security systems, such as pension, health care and livelihood protection, total approximately 46 trillion yen (data for fiscal 2015). Surprisingly Employees’ Pension Insurance receives the largest portion of those taxes (20%), because taxes cover half of the basic pension portion. The consumption tax paid by low-income earners is allocated to people who retired from major listed companies. Meanwhile, the amount of pension paid to low-income earners is reduced, because they cannot pay premiums sufficiently. This situation seems unfair. Employees’ Pension Insurance covers relatively wealthy people. Is it appropriate to support them uniformly through taxes? Taxes also support wealthy elderly people for health care.

Japan treats low-income earners coldly in terms of benefits, too. According to an OECD report in 2008, cash disbursements to people in the bottom 20% of personal income distribution amounted to 16% of all such benefits paid in Japan. Meanwhile, people in the bottom 20% pay 6% of all taxes and premiums. Disbursements to the bottom 20% amount to 25% of all cash benefits in the U.S. and 31% in the U.K., respectively. The burden borne by low-income earners is less than 2% in those countries. It is the same for low-income earners in Japan and Scandinavian countries, but the cash disbursement for low-income earners in Japan is smaller. In Scandinavian countries, low-income earners receive 25% to 30% of all such benefits paid. In short, low-income people in Japan pay more tax but get less benefits.

The poverty ratio and income disparity are greater in Japan than in other OECD members for those reasons. Japan spends a lot on pension, but the poverty rate in Japan is slightly below 20%, the second highest level in the world after the U.S. Japan’s poverty rate is twice as high as that of the U.K. Universal pension and health insurance plans which means everybody is covered are only universal in name. That’s why Japan’s social security is low in cost-effectiveness.

Human capital investment is an urgent issue, but the question remains how. Free education and childcare helps wealthy people more. It could widen gaps and increase unfairness. There is also the idea that universalism, which covers all people, should be adopted for education and social security, instead of income-based selection. I do not object to such idea if Japanese people agree substantial tax increase like Sweden. However, assumptions in Japan differ entirely from those in Sweden, where universalism is adopted. In Sweden, all citizens are required to work and pay high taxes under active labor market programs. Sweden does not permit free rides and is far stricter than Japan on that point. The situation in Japan can be called selectivism, but the need to declare income is expected to disappear if the Social Security and Tax Number System is put into practical use.

Basic reform strategies are to clarify roles assigned to parties in the public and private sectors, make the government responsible for the guaranteed minimum and require medium- and high-income earners to make self-help efforts.

The pension systems should be divided into the basic pension which is the flat amount, fully financed by general tax and the amount proportional to the salary financed by contributions. Poverty is predicted to increase substantially in the future, with elderly women at the center. If the current basic pension is reduced by the automatic adjustment mechanism by economic growth and ageing, called ” Macroeconomic Slide”, it will not be able to cope poverty increase, which will only cause the number of welfare recipients to increase. In my opinion, higher taxes should be imposed on high-income pensioners and the basic pension for them should be reduced.

Similarly, two pillars of health care system should be established, instead of dealing with all treatments through social insurance. The first pillar would guarantee basic and life-related necessary treatments to all citizens, financed by general tax and deal with such treatments by reorganizing the current National Health Insurance system. The second pillar would cover other health care services, and address them through the current health insurance associations or private insurance. Some problems with health care systems in Japan are the excessive consumption of resources because patients can freely see doctors on the demand side, and treatments have not been standardized and their cost-effectiveness has not been sufficiently verified on the supply side. We can secure 2 trillion yen by improving the efficiency of national health care expenditures, totaling 42 trillion yen (in fiscal 2015), by 5 percent.

Taxes must be increased to finance the first pillar, but the hike would cause the current premium burden to fall. Redistribution should also be bolstered in tax systems by taking steps, such as a switch from taxable income deductions to tax credits.

There are also issues that must be addressed before making childcare and education free of cost, such as the establishment of more day nurseries, improved treatment of childcare workers and promotion of the use of childcare leave systems. These issues require immediate attention when great many children are on waiting lists. Programs, such as supplementary after-school lessons for elementary and junior high school children from low-income families, are effective for ensuring equal higher education opportunities. General reforms in higher education, such as the guarantee of funding and quality of education, are assumptions for expanding scholarships and income contingent student loans.

Whether Japan can reform its social security which is largely dependent on social insurance and apply resources to human capital investment, the key to overcoming the falling birthrate and aging population.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 29 December 2017 under the title, “Shakaihosho no miraizu (II): Kun no sekinin saitei hosho ni gentei (Blueprint for the Future of Social Security (II): Limiting State Responsibility to the Guaranteed Minimum).” The Nikkei, 29 December 2017. (Courtesy of the author)