What Do Growth Strategies Need?: Sweeping Away Citizens’ Anxiety Regarding the Future

Key Points

- Growth strategies do not raise corporate and household expectations

- Younger households suppress their consumption to a greater extent in anticipation of lower lifetime income

- Working style reforms are essential for increasing expected lifetime income

Prof. Murata Keiko

The Abe cabinet has approved the Japanese government’s growth strategies (Future Investment Strategies 2018) and Basic Policies for Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform (big-boned policies).

Growth strategies for this year prioritize driverless automatic driving, next-generation healthcare systems and an e-government, among other projects, for realizing Society 5.0. They seek to raise the potential growth rate through technological innovations. The strategies also incorporate various other measures for growth, such as human resources development, working style reforms, regulatory reforms and economic partnerships, as stated in big-boned policies that are growth strategies in a broad sense.

This is the sixth year under the growth strategies adopted by the Abe cabinet. The first growth strategy, which was formulated six months after the inauguration of the second Abe administration in June 2013 (the Japan Revitalization Strategy), was positioned as the third of the three arrows of Abenomics economic policies.

In the Japan Revitalization Strategy, the Abe cabinet considered citizens’ inability to have hopes for their future as a result of economic stagnation to be a serious problem, and took the view that the first arrow of Abenomics (monetary policies) and the second arrow (fiscal policies) lit a lamp of expectation for the future of the Japanese economy. Furthermore, the cabinet explained that it would bring out the maximum power from the private sector to set a course for growth, positioning the switch of the expectations of the respective corporate managers and citizens to actions as a role assigned to growth strategies.

In the period that followed, the Abe cabinet formulated growth strategies every year. Unfortunately, however, I have never heard feedback stating that these strategies enhanced the Japanese economy’s growth potential. The economic growth rate for Japan has remained firm at around 1.3% on average. However, it has not reached the real growth rate of 2%, which the government adopted as its target. A slightly longer grace period may be necessary in order for the growth strategies to produce results in terms of productivity and the potential growth rate, because economic growth is a phenomenon that should be evaluated from the medium- and long-term perspectives.

One thing I can say, though, is that the expectations of companies and citizens for Japan’s economy, which were stressed in the first growth strategy, subsequently ran out of steam. According to the Cabinet Office’s Annual Survey of Corporate Behavior, the real growth rate for the Japanese economy in the next five years predicted by corporations rose slightly from 1.3% in the previous year to 1.5% immediately after the inauguration of the second Abe administration. However, the same rate sank to a level of between 1.0% and 1.1% in the last three years. The growth strategies adopted by the Japanese government are not leading to improved corporate expectations for long- and medium-term growth rates.

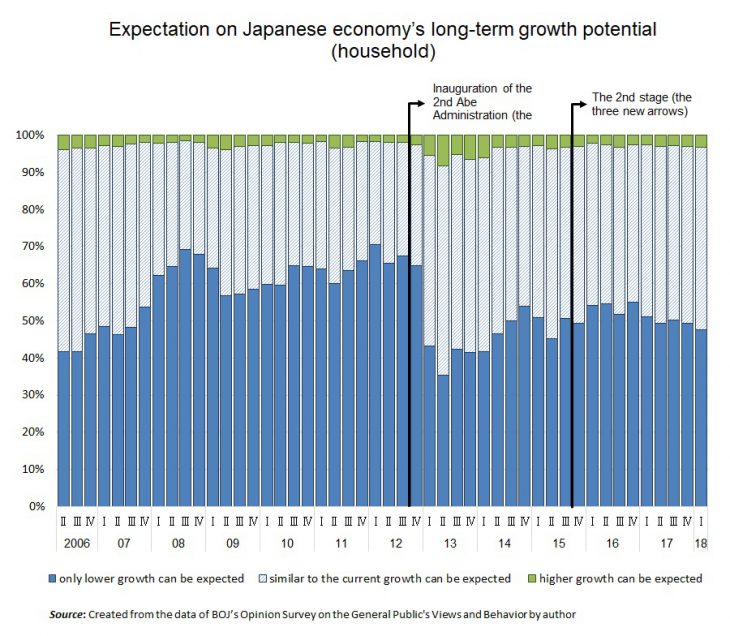

In the meantime, household expectations for the Japanese economy showed a noticeable improvement immediately after the implementation of Abenomics. In a survey that asked households about the Japanese economy’s long-term growth potential, the ratio of the pessimistic answer “only lower growth can be expected” dropped by about 30% at the beginning of 2013. The answer had accounted for more than half of all the replies provided previously in the survey. (See the figure.)

However, the number of people who take a pessimistic view grew again after the summer of 2013 when the third arrow was shot. The situation did not improve in the fall of 2015 when Abenomics moved to the second stage (known as the three new arrows). Growth strategies taken by the Japanese government are not leading to an improvement in household expectations for the future of the Japanese economy, either.

For these reasons, I would like to consider growth strategies from the perspective of households, which are my field of study, in the following section as a point that has not been discussed very extensively.

Looking at the medium- and long-term trends of household expenditure, which accounts for 60% of Japan’s gross domestic product (GDP), the average real expenditure increased at the low rates of 1% from fiscal 2001 to fiscal 2010 and 0.7% in the period from fiscal 2011. Average real disposable income rose 0.6% from fiscal 2001 to fiscal 2010 and 0.5% from fiscal 2011 to fiscal 2016. In particular, growth in this income slowed to 0.4% in the post-Abenomics period from fiscal 2013 to fiscal 2016.

Looking at the contribution of (real) compensation growth for employees to disposable income, the contribution rose 0.1% from fiscal 2001 to fiscal 2010 and 0.6% from fiscal 2011 to fiscal 2016. The contribution showed particular improvement in the post-Abenomics period from fiscal 2013 to fiscal 2016, rising 0.8%. However, taxes and social insurance premiums (including the portions covered by companies) are deducted from disposable income that actually reaches households. Increases in wage income are not leading to disposable income growth due to causes including rises in tax and social insurance premium burdens.

However, household expenditure gradually falls in level after reaching a peak around the age of 50. For that reason, we must keep in mind the impact of aging on consumption from a macroeconomic viewpoint.

Accordingly, I examined medium- and long-term household expenditure trends by householder age group based on data from the Family Income and Expenditure Survey by the Statistics Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (real data with imputed rent adjusted through equivalent exchanges).

To begin with, income dropped gradually among all age groups in the working generation (wage-earner households) in the period from 2000. Income remained relatively firm (in other words, consumption propensity stayed almost unchanged) among households headed by workers in their 50s. On the other hand, households headed by workers in their 40s and 30s controlled consumption more. Their consumption propensity declined as a result.

We can explain this situation by taking the view that expected lifetime income is decreasing more among young people based on the standard life cycle of economics or the permanent income hypothesis. Households do not attempt to lower their expenditure level when they judge a continuing income decline to be a temporary phenomenon and predict that lifetime income will remain unchanged despite the situation. Under these circumstances, consumption propensity should rise as a result. This view is also in accordance with the slowing of a seniority-based wage curve from the medium- and long-term viewpoints.

Consumption propensity has declined substantially among households headed by workers in their 30s, in particular under the observed condition of income hitting the bottom in the last few years. There is a possibility that these households are perceiving their income improvement as a temporary phenomenon.

In the meantime, looking at elderly households, income fell among households headed by people 60 years old or older (the sum of wage-earner households and jobless households) in the period from 2000. In this situation, consumption propensity rose among people in their 60s, 70s and older in the same period.

In the period from 2011, too, consumption propensity showed a gradual increase among households headed by people 70 years old and older. However, a downtrend in consumption propensity was observed in the same period among households headed by people in their 60s. These trends resulted from a decrease in income among people in their 70s due to smaller pension benefits, larger tax burdens and other causes, and a rise in income in their 60s as the ratio of wage-earner households increased.

Positive effects on anticipated personal lifetime income arise when each household becomes able to expect the high growth potential of the Japanese economy. Such change is anticipated to increase consumption.

According to an analysis by Professor Ogawa Kazuo of Kansai Gaidai University (published in this column on December 22, 2017), the consumption growth rate affects corporate growth expectation. This indicates that corporate willingness to invest in plant and equipment will rise and accordingly mechanisms called productivity enhancement and growth rate increase can be expected if growth strategies improve household expectations for economic growth and cause the consumption growth rate to turn upward.

How can we achieve these conditions? I think that the first thing we can do is to become more aware of the strategic problem that growth strategies in the past have not increased corporate and household expectations for the future. The details of growth strategies are important as a matter of course. Whether or not the confidence of citizens can be obtained is equally important. Presenting policies and an economic vision that are easy for all citizens to understand as a package is indispensable in that respect.

For example, we can expect confidence in growth strategies to increase and lead to consumption and investment growth by presenting fiscal and social security forecasts in a straightforward manner, even if their content is harsh, and raising the credibility of policies. In my view, citizens’ anxiety about the future will gradually be alleviated in a situation where these steps have actually been taken.

It is also essential to advance working style reforms at the same time to raise the expected lifetime income of households so that they can increase consumption with a sense of security. That is the second thing we can do.

We should make our labor market neutral and more flexible so that hopefuls can work with a sense of security in exchange for market value proper at a given point in time regardless of their age, sex and job change status. This is a desirable course for the Japanese economy, which is suffering from a manpower shortage, from the viewpoints of enhancing productivity and transferring labor smoothly to divisions with high productivity.

Translated by the Japan Journal. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 28 June 2018 under the title, “Seicho senryaku ni naniga hitsuyoka (I): Kokumin no sakiyuki fuan fusshoku wo (What Do Growth Strategies Need? (I): Sweeping Away Citizens’ Anxiety Regarding the Future).” The Nikkei, 28 June 2018. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Abe administration

- growth strategies

- Future Investment Strategies

- Basic Policies for Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform

- Japan Revitalization Strategy

- lifetime income

- working style reforms

- regulatory reforms

- Society 5.0

- Abenomics

- three arrows of Abenomics

- Annual Survey of Corporate Behavior

- disposable income

- social insurance premiums

- Family Income and Expenditure Survey

- life cycle of economics or the permanent income hypothesis