The Contest for Economic Hegemony in Asia: ASEAN and the Benefits of the US-China Conflict

Hayakawa Kazunobu, Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Developing Economies, Japan

External Trade Organization (JETRO)

Key points

- Exports to the United States and imports from China are both increasing

- Good opportunity to transfer production and attract investment from China

- Risk of trade friction proliferating within the ASEAN region

Hayakawa Kazunobu

The Biden administration, which inherited the trade friction between the United States and China, is strengthening US export control measures day by day. The view from the Association for Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) includes President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines stating that the country will not take sides, while Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong says that Asian countries do not wish to choose between the United States and China.

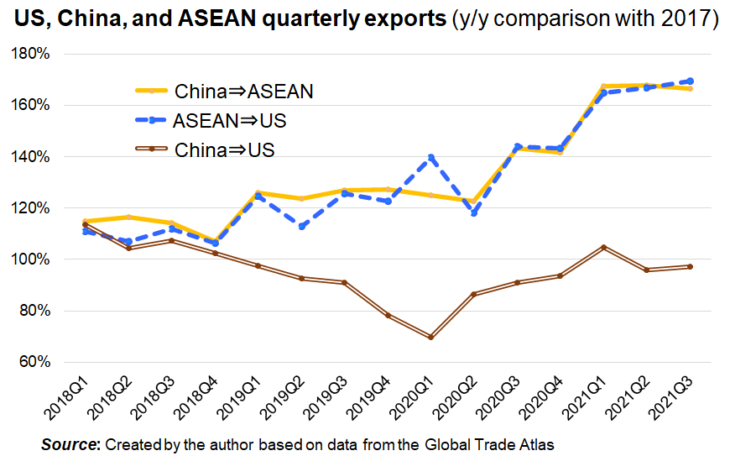

On the one hand, the geographical proximity to China suggests that the ASEAN probably gains the most economic advantage from trade friction between the United States and China. Exports from China to the United States have declined due to the higher tariffs and enhanced export controls that the United States has imposed on China. If we look at the total value of exports from China to the United States on a quarterly basis, we find that there was a particularly significant drop in 2018–19 when the tariffs on China were raised (See figure).

The decrease in Chinese exports to the United States has brought about at least two major changes in the trade environment for the ASEAN countries.

First, replacing China, exports from the ASEAN to the United States are increasing. The total value of exports from the ASEAN to the United States has been increasing continuously since 2019, even during the COVID-19 pandemic. Statistical analyses of the monthly export value from the ASEAN countries to the United States indicate that those exports increase more in the products where the higher tariffs are imposed by the United States on China. The impact on exports from Vietnam, Indonesia, and Cambodia, in particular, is statistically significant.

Some of the expanding exports from the ASEAN to the United States is believed to be the result of Chinese corporations establishing their factories in the ASEAN and of foreign corporations in China shifting a part of the production to their factories existing in the ASEAN.

Little by little, a separation is happening where goods for the Chinese market are made in China, while goods for the United States and other markets are manufactured in the ASEAN. If production is relocated within a multinational corporation, shifting the area of production may not increase profits for the group as a whole, but any expansion in exports and direct inward investment is advantageous to the ASEAN countries.

The second change is that products made in China for the US market have been displaced and are surging onto the ASEAN market. The diagram illustrates the rise in the total export value from China to the ASEAN. There is also a similar trend in exports from the ASEAN to the United States. The two trends are interlinked through the additional tariffs imposed on China by the United States.

In actual fact, statistical analyses of the monthly export value from China to the ASEAN suggests that those exports increase more for the products where the United States impose higher additional tariffs against China. This trend is particularly striking in exports to Vietnam. The rise in exports from China to the ASEAN intensifies competition on the ASEAN market.

So, how do the ASEAN countries respond to the economic changes brought about by the trade friction between the United States and China?

To start with, some ASEAN countries are preparing export control systems that prohibit exports of dual-use (military and civilian) products and related goods to avoid becoming targeted by US export controls. Singapore was quick off the mark, but Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand have also made progress with their preparations since the 2010s. For example, in January 2020, Thailand enacted the Trade Controls on Weapons of Mass Destruction Related Items Act (TCWMD Act), which is more comprehensive than previous systems.

Meanwhile, the ASEAN countries view the US-China trade friction as a good opportunity to transfer production and to relocate corporations from China, and are working hard to attract Chinese investment. Some countries use investment forums, business forums, and other opportunities to attract investment from China, or introduce measures to promote new investment. For example, Thailand has introduced the Thailand Plus investment promotion measure that offers tax incentives to corporations that relocate from China.

In some recent years, the flow of direct investment from China and Hong Kong to the ASEAN has actually exceeded Japan’s direct investment in ASEAN.

ASEAN countries are also cooperating with Huawei Technologies, the Chinese telecommunications giant sanctioned by US export controls. Some countries have installed Huawei equipment and launched commercial services using the 5G high-speed communication standard.

In addition to setting up the Huawei ASEAN Academy in Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and Cambodia, Huawei has concluded MoUs with universities in the ASEAN to develop human resources with expertise in information and communication technologies. Huawei has also signed an MoU with the ASEAN Foundation to eliminate the digital talent gap.

This is how the ASEAN is preparing export control regulations to avoid scrutiny by the United States, encouraging corporate relocation and the transfer of production from China, and strengthening collaboration with Chinese corporations with advanced technologies.

The joint declaration by China and the ASEAN in November 2019 indicates that the plans by the ASEAN to build sustainable infrastructure and digital innovation match up with China’s motives for promoting the Belt and Road Initiative. Furthermore, relations between China and the ASEAN were upgraded to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership at the ASEAN-China Special Summit in November 2021.

On the other hand, the increasing presence of Chinese corporations and the rise in exports of sanctioned items to the United States have caused a new problem: the proliferation of areas of trade friction. Any suspicion of tax avoidance for Chinese-made goods carries a high risk of anti-dumping duty (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) or other measures imposed by the United States.

For example, the United States has imposed AD/CVD duty on corrosion resistant steel and cold rolled steel sheet from Vietnam since 2018 because it was deemed that Chinese corrosion resistant steel and cold rolled steel sheet had circumvented the export sanctions. Since such a measure by the United States may also have direct or indirect impact on exports to the United States by other companies in the same industry, including Japanese overseas affiliates, the ASEAN governments have strengthened their monitoring.

Courted by both the United States and China, the ASEAN has a wide range of policies at its disposal and is trying to profit as much as possible from the US-China trade friction. This is consistent with long-lasting ASEAN diplomacy, which is to maintain good relations with all major countries outside the region while gaining economic advantage. On the other hand, they also need to be wary of an excessive Chinese presence so these are difficult waters to navigate. In addition, if the US-China conflict intensifies, the ASEAN will be pressed to choose between the United States and China.

In recent years, some voices in the ASEAN have pointed to a declining Japanese presence, but it is more important than ever to strengthen cooperation with Japan, another major power in Asia, to mitigate the influence of the United States and China. The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP), which includes neither the United States nor China currently, may play an important role. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which came into force on January 1, 2022, is also likely to strengthen international production networking with Japanese corporations.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 17 January 2022 under the title, “Ajia no Keizaihaken-arasoi (III): ASEAN, Beichu tairitsu de onkei (The Contest for Economic Hegemony in Asia (III): ASEAN and the Benefits of the US-China Conflict).” The Nikkei, 17 January 2022. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Hayakawa Kazunobu

- Institute of Developing Economies

- JETRO

- ASEAN

- US-China trade friction

- export control

- Chinese exports

- ASEAN exports

- Huawei ASEAN Academy

- ASEAN-China Special Summit

- TPP

- RCEP