Don’t Be Swallowed by the Two Dystopias of the US and China—What is the “world-historical mission” that only Japan can fulfill?

[…] with the momentum of becoming the world’s second largest economic power, China strengthened its geopolitical expansionist stance while suppressing Hong Kong’s autonomy and strengthening its system of surveillance of individuals. The “rising star” [of the developing world] became a “dystopia.”

On March 4, 2024, the Nikkei Stock Average briefly broke through 40,000 yen (40,109.23 yen), reaching an all-time high that surpassed the bubble period (38,915.87 yen on December 29, 1989). There is currently an optimistic mood in Japan about the economic outlook. However, I am not optimistic about the current state of the world economy surrounding the Japanese economy. This is because what we are witnessing now is the interruption of the “globalization” that followed after World War II and the chaos accompanying it.

“The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep; he could at the same moment and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world, and share, without exertion or even trouble, in their prospective fruits and advantages.”

This is a passage from The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919) by John Maynard Keynes, describing the life of the British middle class before World War I. If you replace “by telephone” with “by a click,” it would be no different from the lives of the middle classes around the world today. In other words, there have been two “globalizations” in modern history. The “first” globalization began in the 1820s. With the development of transportation and communication technologies such as railroads and telegraphs, the volume of global trade and capital transactions increased dramatically, reaching a scale comparable to that of today.

Globalization brings great “benefits” to humanity by raising incomes around the world and reducing poverty in many of the developing countries. As the 19th-century British economist David Ricardo theorized, globalization allows countries to export what they have a comparative advantage in and import what they have a comparative disadvantage in, thereby increasing productivity worldwide. However, this very process inevitably creates “losers” within each country. This is because, while industries with comparative advantages flourish, industries with comparative disadvantages decline and the wages of workers and the prices of the resources these industries need fall. This means that if the “winners” do not provide the policies and systems to support these “losers,” the “losers” will rebel against globalization, causing globalization itself to collapse.

Kuznets’ Law and Montesquieu’s Law

The first globalization took place under the hegemony of the British Empire, but it was an era of “liberalism.” Although there were the seeds of welfare policies and labor movements, liberalism eventually lost sight of the “losers,” and this discontent destabilized domestic politics and international relations, ending with the outbreak of World War I in 1914. This was followed by the rise of fascism, the Great Depression, and finally World War II.

After World War II, reflecting on the failure of the “first globalization,” the “second globalization” began under the leadership of international organizations called GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) and its successor WTO (World Trade Organization). Behind this was a faith in two empirical “laws.” One was the “Kuznets Law” or “Kuznets curve.” This law states that once a certain level of per capita GDP is reached through industrialization, democratization and the rise of the welfare state will allow more people to benefit from economic growth, reducing income inequality. The other is what I call “Montesquieu’s Law.” In The Spirit of the Law (1748), the French thinker Montesquieu argued that “commerce is a cure for the most destructive prejudices. […] and wherever there is commerce, manners are gentle.” This can be modernized as the law that the development of capitalism liberates people from narrow patriotism and nationalism and leads them to accept basic principles of “modernity” such as “democracy,” “rule of law,” and “freedom of thought.”

In fact, at the beginning of the second globalization, both Kuznets’ Law and Montesquieu’s Law were in operation. The rapid growth of developing countries, especially China, caused the absolute poverty rate in the world to plummet, and democratization and liberalization progressed in many East Asian and some socialist countries. Indeed, it was also an era of happy globalization in which incomes in developed countries were equalized by Keynesian policies and the welfare state.

After 1980, however, globalization took a dark turn.

Why has America entered a dystopia?

In 1981, the Ronald Reagan administration came to power in the United States and, together with the Margaret Thatcher administration in the United Kingdom, strongly promoted laissez-faire economic policies. This was based on the central idea of neoclassical economics led by Milton Friedman (1912–2006). The idea was that the more government intervention was eliminated and the more the markets were purified, the more efficient and stable the capitalist economy would be. The second globalization, which began in the 1980s, was a grand experiment of this idea, attempting to cover the entire globe over with all kinds of markets. And then came the financial revolution, which securitized all risks and time differences, and the IT revolution, which made it possible to transmit information and transfer funds instantly with a single click. The American economy, riding the waves of these two revolutions, achieved unprecedented high growth. Then, with the collapse of the socialist systems in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in 1991, American-style capitalism, with its “laissez-faire doctrine” and “shareholder sovereignty,” became the single “global standard.”

In the 21st century, however, the instability and inequality inherent in laissez-faire capitalism and shareholder-orientated corporate system have become apparent. Take, for example, the recurrent financial crises. Globalized financial markets are intricately interconnected, and local disruptions can instantly spread around the world. We experienced this instability in 2008 with the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), which originated in the United States.

Moreover, under the doctrine of shareholder sovereignty, which states that “the social responsibility of business corporations is solely to maximize profits for their shareholders,” inequality in the United States increased significantly when shareholder interests were prioritized over worker employment and the stability of local communities. Stock prices soared, as did the compensation of the managers who helped drive them, while payments to workers stagnated. Particularly hard hit were the workers in heavy industries who lost out to cheap foreign products and labor-saving innovations, but the United States, following the laissez-faire doctrine, did not reach out to these “losers” to any significant degree. Meanwhile, IT entrepreneurs are reaping huge profits from the globalization of the market. As a result, according to the World Inequality Database, the top 1% of income earners now receive 20% of all income. America has returned to an unequal society comparable to that of the pre-World War II era, destroying Kuznets’ Law.

This destabilization and unequalization of American society led to Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election. The “losers” of globalization became ardent supporters of Trump’s “America First” policy. Moreover, his rhetoric that globalization is merely the ideology of liberal elites, who champion abstract concepts such as “democracy,” “rule of law,” and “freedom of thought,” resonated deeply with white men who felt threatened by the advancement of women and non-whites—advancements brought about by these very democratic ideals. The scene of his supporters refusing to accept the loss of the 2020 presidential election and storming the US Congress, which is supposed to be the hall of democracy, is still fresh in our minds.

In the post-World War II era, the United States led the way in promoting the basic principles that underpin modern society — principles such as “democracy,” “rule of law,” and “freedom of thought” — principles that were shared by other developed countries. However, a huge force hostile to these very principles has emerged in the middle of America itself, causing deep division within its society. The United States, once regarded as the “global standard,” has suddenly turned itself into a “dystopia.”

China has fallen from being a “rising star”

In 1978, under Deng Xiaoping, the socialist China began its “reform and opening-up,” introducing capitalist policies. Since 1980, it has achieved 30 years of high growth, and in 2011 it overtook Japan to become the world’s second largest economic power. China has become a “rising star” among developing countries.

In 2012, however, Xi Jinping became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). This was a time when many Western countries were still recovering from the Great Recession caused by the GFC. Learning from the plight of the West, China began to equate the basic principles of modern society such as “democracy,” “rule of law,” and “freedom of thought” with “Western values,” and began to seek a “great ‘rejuvenation’ of the Chinese nation” in opposition to Western values. Then, with the momentum of becoming the world’s second largest economic power, China strengthened its geopolitical expansionist stance while suppressing Hong Kong’s autonomy and strengthening its system of surveillance of individuals. The “rising star” turned itself also into a “dystopia.” It destroyed Montesquieu’s Law and (together with other anti-Western authoritarian states, including Russia, North Korea, and Iran) caused a great division in the global world.

The world is now in the midst of the chaos that comes with the interruption of the “second globalization.” Both the United States, which led the second globalization, and China, which benefited most from it, have now become “dystopias.”

The “first globalization,” which began in the 1820s, ended with World War I in 1914 and ushered in a dark age. How can we prevent the “second globalization” from repeating its mistakes and ushering in another dark age? To answer that question, let’s start with China.

Why is China’s economy in trouble?

In fact, the solution to avoid becoming a “dystopia” like China can be found within China itself.

China’s high growth since the 1980s is no miracle. It is a typical outcome of the mechanism of “industrial capitalism.” The industrial revolution in the 18th century made it possible to create the “factory systems” that use a large number of workers for mass production, and industrial capitalism is a form of capitalism that generates profits by investing in these factory systems. However, there is an important prerequisite for this mechanism: the existence of “surplus population” in rural areas. No matter how high the productivity of these factories, if the wages of the workers are high, there will be no profits. The wages of the factory workers must be kept low by the constant influx of people from rural areas who can barely make ends meet. Conversely, as long as there is an abundance of low-wage workers, investment in factories will almost certainly generate profits. If these profits are reinvested, high growth can be almost automatically achieved.

This mechanism of industrial capitalism works in free economies as well as in state-led economies. In fact, as Alexander Gerschenkron (1904–78) once argued, it may work even better in state-led economies in the case of latecomer countries. And after opening up, China, which had a huge surplus population in its rural areas, attracted large amounts of capital from developed countries and became “the world’s factory system” during the second globalization.

But industrial capitalism inevitably comes to an end. Fundamentally, profits in capitalism are brought about by “differences.” In the Age of Discovery, before the Industrial Revolution, commercial capitalism generated enormous profits because there was a large “price difference” with distant regions. And indeed, profits in industrial capitalism were also generated simply by the “difference” between the high labor productivity of factory systems and the low wages of workers flowing from rural areas. But as industrial capitalism expands, it will eventually exhaust the rural surplus population. This depletion would drive up the wages of factory workers and erase this “difference.” Consequently, merely investing in factory systems no longer yields profits. In fact, this is what happened in the United States in the 1950s, in Europe in the 1960s, in Japan in the 1970s, and in South Korea and Taiwan in the 1990s.

As a result, business corporations are forced to consciously create “differences.” They now have to generate profits by developing new technologies, new products, new management styles, and new markets. In other words, this is a transition to capitalism in which “innovation” becomes the major source of profits. This is the form of capitalism we call “post-industrial capitalism.”

But post-industrial capitalism also has an important prerequisite. Innovation requires infrastructure such as the thorough implementation of democracy and the rule of law that protects freedom of thought and private property. Let’s say there are authoritarian states where the authority of the political party takes precedence over democracy and the rule of law. Even if you succeed in innovation, if it infringes on the interests of the party, your intellectual property rights may not be protected. If your success threatens the party’s authority, you will not know whether you can even secure your own freedom. If that happens, you will have little motivation to continue research and development or to start a new business. Then, you are more likely to make money by doing business through “connections” with those in power, or by speculating on bubbles in the stock and real estate markets.

The Chinese economy is now in a difficult situation. The immediate trigger was the forced lockdown as a countermeasure against the new coronavirus starting in 2020. The collapse of the real estate bubble has made matters worse. But behind theses immediate causes lies a more fundamental problem. That is of course the exhaustion of surplus population in rural areas. And it already started around 2010. In other words, China had long been in a situation where it would be difficult for it to continue to grow unless it transitioned to post-industrial capitalism.

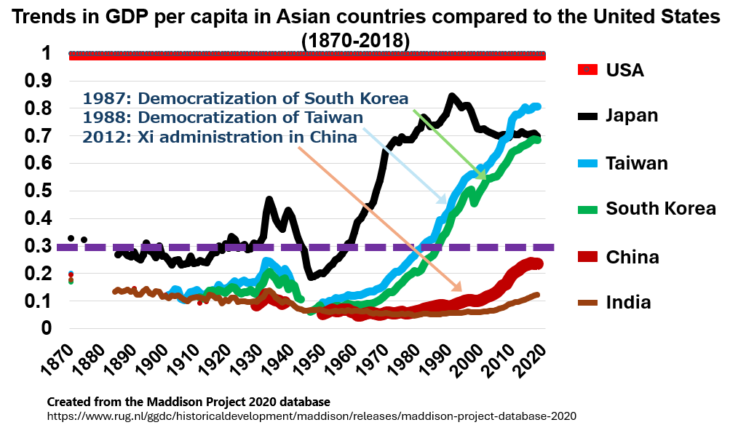

There are some interesting statistics. This is a graph that traces the relative ratio of the per capita GDP of selected Asian countries to that of the United States. Of particular note is the period when each country’s per capita GDP exceeded 30% of that of the United States. In the prewar period known as the Taisho Democracy (1910s–1920s), Japan’s per capita GDP exceeded 30%, but it fell during the war and did not exceed 30% again until the late 1950s after the war. South Korea and Taiwan exceeded 30% in the late 1980s. It was also the time that both countries democratized and liberalized their economies. In South Korea, the “June Democratic Struggle” demonstration against the military regime took place in 1987, and in Taiwan, Lee Teng-hui became president in 1988, accelerating democratization. Since then, the per capita GDP of both countries has continued to grow steadily and is now around 80% of that of the United States, surpassing even that of Japan, which has stagnated at around 70%.

Xi Jinping vs. Jack Ma

In contrast, while China’s GDP per capita has certainly grown rapidly since the reform and opening up in 1978, it has never reached 30% of the US. And just as the rural surplus population began to dry up, in 2012 to be exact, Xi Jinping became general secretary of the CCP. As noted above, democratic governance and the rule of law that protects freedom of thought and private property are essential to the transition to post-industrial capitalism, as they provide the infrastructure that makes it easier for individuals and firms to innovate. But on the contrary, the Xi administration has become more nationalistic and socialistic than ever, and in recent years, for example, it has imposed huge fines on Alibaba, founded by Jack Ma, and instead has increased regulation and surveillance on IT entrepreneurs and capitalists who try to innovate. And just around 2012, the growth rate of GDP per capita began to slow. Unlike Taiwan and South Korea, which have continued to grow through democratization and liberalization to more than 30% of America’s per capita GDP, China has yet to break the 30% barrier.

I mentioned earlier that Montesquieu’s Law has collapsed. But that was a rash statement. In fact, in The Spirit of the Law, Montesquieu also said, “it is almost a general rule that wherever manners are gentle there is commerce,” before saying, “wherever there is commerce the manners are gentle.” In other words, he not only points out the causal relationship in which the development of capitalism promotes modernization, but also the existence of a reverse causal relationship in which the establishment of modern society promotes the further development of capitalism. Comparisons between China and Taiwan, South Korea and the former Japan show exactly this reverse causality.

The way to avoid being swallowed by China’s “dystopia” is now clear. They are the most obvious of all: to establishing and maintain “the basic principles of modern society” such as “democracy,” “the rule of law” and “the freedom of thought.” It is also a reaffirmation of Montesquieu’s Law in its extended form.

Japan’s “World Historical Mission”

In 1942, in the midst of World War II, a special feature on the theme of “overcoming the modernity” (kindai no chokoku) was published in the Japanese literary magazine Bungakukai, whose publisher, Bungeishunju-sha, is also the publisher of Bungei Shunju, in which this interview was originally published. In an essay for this special issue, which is said to have attempted to provide ideological justification for Japan’s war effort through the concept of “overcoming modernity,” Kyoto School historian Suzuki Shigetaka (1907–88) stated the following: “Overcoming the modernity means… overcoming democracy in politics, overcoming capitalism in economics, and overcoming liberalism in ideology.” The “democracy,” “capitalism,” and “liberalism” listed here as the essence of “modernity” roughly correspond to the “democracy,” “rule of law,” and “freedom of thought” that I also listed in this interview as the essence of “modernity”. (The “rule of law” includes the protection of private property, which is the institutional foundation of “capitalism”). What is important here is that after the above passage, Suzuki Shigetaka equates this “modernity” with “European civilization” and links the ideological task of “overcoming the modernity” with the practical task of “overcoming European world domination.”

I don’t know how Suzuki Shigetaka’s ideas related to the actual war effort. But it was certainly the clearest expression of the Zeitgeist in Japan during World War II. And the idea of equating “modernity” with “Western values” and aiming to “overcome” them is being repeated right now by China under the Xi administration (and other authoritarian states). It is also being repeated, albeit in a diluted form, by Trump supporters in the US (and by populists of both the left and the right in other advanced capitalist countries).

Now the “second globalization” has been interrupted, and we are in the midst of the chaos that comes with it. We are on the verge of whether the “second globalization” will follow in the footsteps of the “first globalization” and enter another dark age. This may be a grandiose way of putting it, but I believe that this is where Japan’s “world-historical mission” can be found.

Japan was the first country outside Europe and the United States that succeeded in modernization. At the same time, it is also a country that had once fallen into decline by preaching the aforementioned “overcoming modernity” during the period of chaos following the end of the “first globalization.” But, during the “second globalization” after World War II, it again pushed forward “modernization” and achieved a certain degree of freedom, prosperity and peace. In doing so, it demonstrated the fact that the basic principles of modern society, such as “democracy,” “rule of law,” and “freedom of thought,” are not necessarily “Western values.”

Moreover, after the “second globalization,” Japan has allies. Taiwan and South Korea, located in East Asia far from Western Europe, have already succeeded in creating modern societies based on these “fundamental principles.” In this sense, together with these modernized non-Western countries, Japan has been given a duty, or even a “world-historical mission,” to continue to demonstrate that the “basic principles of modern society,” such as “democracy,” “rule of law,” and “freedom of thought,” are truly “universal ideals” in the truest sense of the word, with Western society being its special version.

The “Theoretical Fallacy” of the Laissez-faire Doctrine and Shareholder Sovereignty

My story doesn’t end here, because we haven’t yet talked about the “dystopia” that is America.

It is clear that America became a “dystopia” because its capitalism is based on laissez-faire doctrine and shareholder sovereignty (and the fact that its political system is based on presidential government prone to populism also contributed greatly).

However, what I want to emphasize here is that both laissez-faire doctrine and shareholder sovereignty are “theoretical fallacies” (as I have argued for many years in works such as Disequilibrium Dynamics, Kaheiron [Monetary theory], and Kaisha wa Korekara Donarunoka [What will become of business corporations?]).

First, the laissez-faire doctrine is a fallacy that ignores the fact that the capitalist economy is a monetary economy. People do not receive money in order to use it as a material object. They receive it only because they expect others to receive it as money in exchange of goods. In this sense, even if people are not aware of it, they are actually speculating every time they receive money. Speculation is almost always accompanied by bubbles, and these bubbles are bound to burst. A bubble in money is a situation in which people want money, which is merely a medium of exchange for goods, more than the goods themselves. It thus dampens effective demand for goods and leads to a recession. The bursting of a bubble in money is a situation in which people dump money to get concrete goods. It thus boosts effective demand and causes inflation. When a recession becomes severe, it becomes a depression, and when inflation becomes severe, it becomes hyperinflation. In other words, capitalism is an inherently unstable system that is constantly at risk of depression and hyperinflation because it is a monetary economy.

Furthermore, shareholder sovereignty is a fallacy that ignores the fact that a business corporation is not a mere firm but a firm that is incorporated. It is the corporation as a legal person, not the shareholders, that owns the factories and offices, makes contracts with employees, suppliers, and banks, and becomes the litigant in court. It is also the managers, not the shareholders, who actually run the business corporation as a legal person. Unlike shareholders, who can sell their shares at any time in markets, managers have a duty of loyalty to their corporation. This is nothing more than an ethical duty not to use the corporation as an instrument of self-interest once they have assumed the role of running the corporation as a person.

Capitalism cannot stand alone in the marketplace

However, American corporate systems adopted a compensation system centered on stock options, claiming that in order to give managers an incentive to maximize shareholder profits, they should also be made shareholders too. Unfortunately, this only freed managers from the duty of loyalty and gave them the opportunity to use the corporation as a tool for their own interests. Taking advantage of this opportunity, managers of large corporations have increased their compensation to 350 times that of the average worker. As noted above, the World Inequality Database shows that the top 1% of high earners in the United States receive 20% of total income, but if we further look at the breakdown of that income, the share of capital income is relatively small, stark contrast to the pre-war period when capital income claimed the lion’s share. Entrepreneurial income constitutes a large share, reflecting the age of post-industrial capitalism, but an even larger share consists of wages, salaries and pensions. But, don’t get me wrong. It is not the wages, salaries and pensions of ordinary workers, but rather those of corporate managers. This underscores that the root cause of inequality in the United States is the fallacy of shareholder sovereignty.

Now, if the laissez-faire doctrine is a theoretical fallacy, the capitalist economy cannot stand on its own in the marketplace. It can only function stably in combination with government regulation, central bank intervention, social security system, an ethos of mutual assistance, etc. It means that capitalism itself will have “diversity” depending on how it combines markets with other institutions.

If shareholder sovereignty is a theoretical fallacy, then a business corporation will no longer be a mere money-making machine for shareholders. It will have autonomy as a human organization, and as long as it is making a positive profit, it is possible for it to include not only the interests of shareholders, but also the interests of employees and other stakeholders, and even the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). The corporate system itself will have “diversity” depending on how its objectives are set and how the organization is structured to achieve them.

Show the diversity of modernity

Here, Japan’s other “world historical mission” becomes evident.

It is to demonstrate the “diversity” of capitalism, the “diversity” of corporate systems, and, more broadly, the “diversity” of “modernity.”

That is not a difficult task, as the Japanese form of capitalism and corporate system have historically demonstrated that these concepts indeed possess “diversity.”

Moreover, this diversity is not merely the matter of American-style capitalism vs. Japanese-style capitalism, or Western corporate system vs. non-Western corporate system. For example, the Japanese corporate system, historically characterized by an emphasis on employee employment and organizational continuity rather than the pursuit of profits for shareholders, shares commonalities with the corporate systems in Germany, France and some of European countries. The important point is that this diversity spans both Western and non-Western countries, with one style being American and the other encompassing European and Japanese systems. In other words, it is precisely by being situated in a non-Western context that Japanese capitalism and corporate system have demonstrated that their diversity is diversity in the truest sense.

This does not mean that Japan can remain complacent. Unfortunately, since the 1990s when American-style capitalism came to be seen as the global standard, Japan, always one step behind, attempted to adopt shareholder sovereignty. And it failed. Now that the dark clouds of deflation that hung over the Japanese economy for three decades are finally starting to disappear, it is time for Japan to take the helm once again and reaffirm its world historical mission.

Translated from “Sekigaku ga Miru Kinmirai no Sekai: Futatsu no Disutopia BeiChu ni Nomikomareruna—Nihon ni shika hatasenai ‘Sekaishiteki Shimei’ towa (The world of the near future as seen by a profound scholar: Don’t Be Swallowed by the Two Dystopias of the US and China—What is the ‘world-historical mission’ that only Japan can fulfill?),” Bungeishunju, June 2024, pp. 116–125. (Courtesy of Bungeishunju, Ltd.) [July 2024].

Keywords

- Iwai Katsuhito

- Kanagawa University

- University of Tokyo

- Disequilibrium Dynamics

- economic outlook

- capitalism

- first globalization

- second globalization

- David Ricardo

- John Maynard Keynes

- Milton Friedman

- Kuznets’ Law

- Kuznets curve

- Montesquieu’s Law

- global standard

- dystopia

- United States

- China

IWAI Katsuhito, Ph.D.

IWAI Katsuhito, Ph.D.