India After the General Elections: A return to economic reform is essential

The light and shadow of Mumbai, India, where rapid economic growth continues… Professor Sato Takahiro points out, “the Indian people feel that they are being left behind in economic development due to the Modi government’s preference for big business, while suffering from the triple economic problems of unemployment, rising prices and poverty (underdevelopment). The general election was a natural outcome reflecting this public opinion.”

Photo: f9photos / PIXTA

Key Points:

- The Modi administration has delayed one economic reform bill after another.

- People are facing a triple whammy of unemployment, rising prices and poverty.

- The Modi administration should not succumb to resistance and should move away from protectionism.

India’s national elections were a major disappointment to the ruling party’s expectations, with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) winning only 240 seats, far short of the 272 seats needed for a single majority. Even with the cooperation of powerful regional parties in its coalition, the Narendra Modi administration was barely able to launch its third term.

The BJP lost 63 seats from the previous election. Investors at home and abroad were concerned about the instability of the government, and Indian stock prices plunged immediately after the vote count. The amount of wealth lost on the day of the vote count was the equivalent of about 60 trillion yen. The Modi administration is off to a rocky start.

◆◆◆

Underlying the election results is the economic mismanagement of the Modi administration over the past decade. In addition to the abolition of the most expensive banknotes, which suddenly scrapped 86% of the currency in circulation in November 2016, the world’s most powerful lockdown was implemented in March 2020 without adequate preparation, unnecessarily disrupting the economy. These economic policies only caused unnecessary pain to small businesses and migrant workers in the cities. Both policies have caused the economy to decline to the point of extreme deterioration and have created massive unemployment.

The Modi administration also heavily protected uncompetitive, low-tech, labor-intensive industries such as footwear, textiles, and furniture, in particular, by raising tariff rates on one-third of traded goods starting around 2015. Moreover, in negotiations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement in East Asia, India suddenly withdrew from the agreement in November 2019 after being asked to liberalize the import of dairy products. These backward protectionist policies have led to India being overtaken by its neighbor Bangladesh in terms of per capita gross domestic product (GDP).

However, this does not mean that the Modi administration has not undertaken any economic reforms. For example, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code of 2016, which accelerated the metabolism of the Indian economy, allowed Nippon Steel and ArcelorMittal to successfully acquire bankrupt Indian companies. In addition, the Goods and Services Tax (GST), introduced in 2017, unified indirect taxes that had been imposed independently by the central and state governments. The introduction of the GST also abolished domestic customs duties, a landmark contribution to the unification of India’s domestic market. The Modi administration also managed to privatize the national airline, Air India, in 2022.

On the other hand, the amendment to the 2013 Land Acquisition Act, which is an impediment to infrastructure development, was enacted as an interim law in late 2014, but it failed to get a majority in Parliament and was scrapped in 2015. Since then, the Modi administration has not revisited the issue of amending the Land Acquisition Act, which has hampered the progress of infrastructure development. India also faces the problem that 20 to 30 percent of agricultural products, especially fresh produce, are damaged during distribution. Agricultural laws aimed at modernizing agricultural logistics were enacted in 2020 despite opposition from political parties, but had to be repealed within a year due to massive and sustained protests by hundreds of thousands of farmers. The laws also helped standardize contract farming involving private companies, but their repeal has further delayed the efficiency of India’s agricultural sector.

In addition, the Labor Codes, enacted from 2019 to 2020, consolidated 44 labor laws that had accumulated since colonial times into four codes. It aimed to reform India’s outdated and rigid labor law system by combining employment flexibility, including a gradual relaxation of dismissal restrictions, with the inclusion of workers in the social security system. However, the Modi administration, fearing that trade unions would create a situation similar to the large-scale protests against the agricultural laws, postponed the implementation of the labor codes due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and there is still no prospect of the implementation.

Thus, it must be said that the decade of the Modi administration has been a history of capitulation to the forces of resistance to economic reform.

In fact, according to a public opinion survey by the Center for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), India, 23% of people cited rising prices and unemployment as unfavorable issues facing the Modi administration, and 10% cited poverty.

The biggest factor in deciding whether to vote in the general election was unemployment (27%), followed by rising prices (23%) and economic growth (13%). An India Today poll also found that 52% of respondents said that big business had benefited the most from the Modi administration.

In other words, the Indian people feel that they are being left behind in economic development due to the Modi government’s preference for big business, while suffering from the triple economic problems of unemployment, rising prices and poverty (underdevelopment). The general election was a natural outcome reflecting this public opinion.

◆◆◆

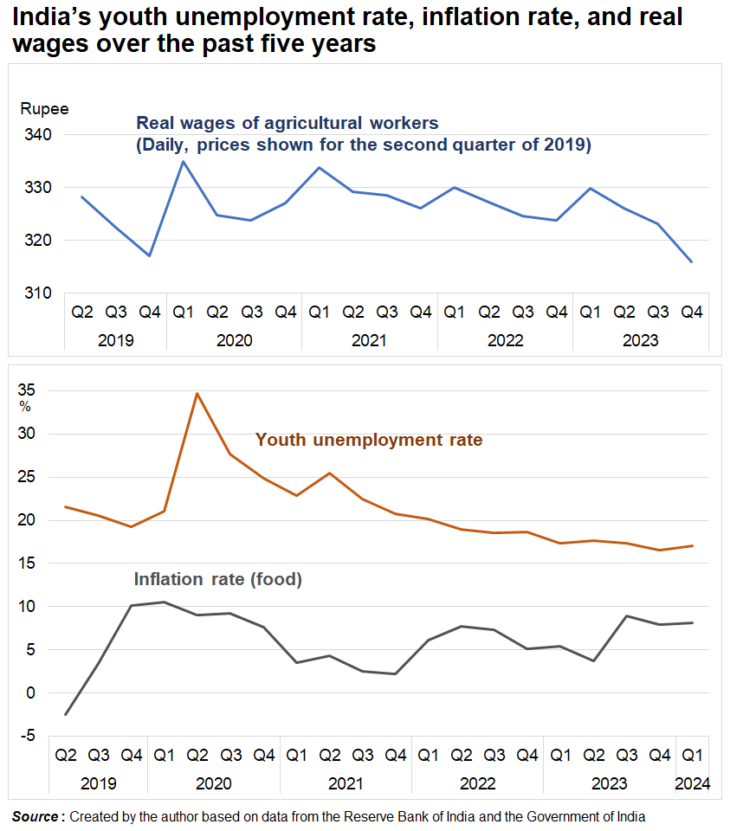

The figure shows the data confirming the triple whammy of unemployment, rising prices, and poverty.

First, we looked at the quarterly unemployment rate of young people aged 15 to 29 in urban areas, who account for approximately 40% of India’s total economically active population. The unemployment rate was 21.6% in the second quarter of 2019, when the second term of the Modi administration began, but rose to 34.7% in the second quarter of 2020 due to the lockdown that began in March of that year.

Supported by the gradual lifting of the lockdown and the economic recovery from 2022 onwards, the unemployment rate has continued to decline since then, reaching 17.0% in the first quarter of 2024. The unemployment rate has fallen by 4.6 percentage points over the past five years, but it has not fully met the expectations of the Indian people.

Second, the inflation rate in the figure is the year-on-year change in the consumer price index for food. It was minus 2.5% at the beginning of the second administration, but rose to 10.5% in the first quarter of 2020. It then fell to 2.2% in the fourth quarter of 2021 due to the economic downturn caused by the lockdown. Since then, however, inflation has risen due to the domestic economic recovery and rising global oil prices. And in the first quarter of 2024, it rose to 8.1%.

In India, there is a well-known rule of thumb that if the inflation rate exceeds 10% in the year before an election, there will be a change of government. An inflation rate approaching 10% is one of the reasons why Indians voted for the opposition coalition instead of the ruling BJP.

Third, as a proxy variable for poverty, the figure shows the trend in the daily real wage of agricultural workers. Agricultural workers form the majority of the absolute poor in India. Real wages, which were 328 rupees (about 500 yen) in the second quarter of 2019, have barely increased over the past five years and were 316 rupees in the fourth quarter of 2023. Despite India’s recent economic growth rate of over 8%, poverty is worsening.

Simply focusing on the current high rate of economic growth and the boom in asset prices in real estate, equities and other assets is not enough to understand the triple burden faced by the Indian people.

The third Modi administration is being asked by the people to focus on resolving the triple whammy. In order to solve the unemployment problem in the long term, in addition to the prompt implementation of the Labor Codes, it is necessary to break away from protectionism and return to the path of economic reform so as to develop export-oriented and highly competitive labor-intensive industries. In addition, improving the supply capacity of the Indian economy by modernizing agricultural logistics and accelerating infrastructure development should contribute to long-term price stability. As well as benefiting the poor through economic growth, it is also important to develop a safety net to prevent the poor from being adversely affected by economic downturns and rising prices.

It remains to be seen whether the third-term Modi administration will consistently pursue these high-road policies.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 19 June 2024 under the title, “Sosenkyogo no Indo (II): Keizai-kaikaku-rosen eno Fukki, Hissu (India After the General Elections (II): A return to economic reform is essential),” The Nikkei, 19 June 2024. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Sato Takahiro

- Kobe University

- India

- election

- stock prices

- Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)

- Narendra Modi

- third term

- banknotes

- lockdown

- economy

- protectionism

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code

- Goods and Services Tax(GST)

- domestic customs duties

- Land Acquisition Act

- agricultural laws

- Labor Code

- unemployment

- rising prices

- inflation

- poverty

- wages

SATO Takahiro, Ph.D.

SATO Takahiro, Ph.D.