An Examination of Osaka Ishin’s Fiscal Management: Social divisions concealed by universalism

In the nationwide local elections held on April 9, 2023, Osaka Ishin showed its growing influence in local elections in the Kinki region. “I would like to continue to pay close attention to whether Osaka Ishin will approach the dynamics of social exclusion in modern urban public finance and whether other political parties will offer alternatives,” says the author.

Photo: Sakura Ikkyo / PIXTA

Yoshihiro Kensuke, Professor, Momoyama Gakuin University

What is Osaka Ishin’s fiscal management?

In the nationwide local elections held on April 9, 2023, Yoshimura Hirofumi and Yokoyama Hideyuki of the Osaka Restoration Association (Osaka Ishin no kai, hereinafter Osaka Ishin) were elected as Osaka Governor and Osaka Mayor, respectively. For 12 consecutive years since 2011, the heads of Osaka Prefecture and Osaka City have been chosen from Osaka Ishin. Moreover, in the Nara Prefectural gubernatorial election, Yamashita Makoto, an official candidate of Osaka Ishin, became the first to be elected in an election outside of Osaka Prefecture, revealing that support for Osaka Ishin has spread in the Kinki region.[i]

Osaka Ishin held two referendums in 2015 and 2020 to gauge support for the Osaka Metropolis Plan. Both referendums were narrowly voted down, signaling the end of what has been a hallmark policy for Osaka Ishin [as a regional political party] for more than a decade, which might suggest that Osaka Ishin has reached a turning point. However, as indicated in the aforementioned nationwide local elections, even after the rejection of the hallmark Osaka Metropolis Plan, Osaka Ishin’s political influence has in fact been growing in the Kinki region.

It has been argued that residents have appreciated Osaka Ishin’s policies, which has borne fruit in the election results.[ii] Moreover, Osaka Ishin itself has repeatedly touted the “effects” of its policies.[iii] However, as far as I can see, previous research on Osaka Ishin has focused on an analysis of voting behavior in political science, making it difficult to claim that the policy contents and the results of administrative management have been sufficiently studied.

In this paper, based on my previous research,[iv] I clarify what policies Osaka Ishin has implemented from the perspective of management of local finances.

Characteristics of Osaka City fiscal management by Osaka Ishin

・It did not become small government

The 2011 Osaka City mayoral election, with the then Osaka Governor Hashimoto Toru doing a crossover election [by standing in the mayoral election], resulted in the heads of both Osaka Prefecture and the City coming from Osaka Ishin.

Together with the advocacy of the Osaka Metropolis Plan and other centerpiece policies, there was criticism of conventional Osaka City management for being an organization that induces benefits but without benefitting the majority of Osaka citizens, calling it the “Nakanoshima family.”[v] In light of this problem awareness, what fiscal management was implemented by Hashimoto, Yoshimura, and Matsui Ichiro as leaders of Osaka Ishin [as Governor of Osaka Prefecture and Mayor of Osaka]?

Osaka Ishin has frequently called for “decisive reform” and has repeatedly spoken of cutting government spending. Criticism of Osaka Ishin’s political stance has also centered on arguments about neo-liberal “small government.”

Even so, Osaka City’s per capita expenditures have remained around a deviation value of 75, which is higher than other ordinance-designated cities when looking at standard deviation, even after Osaka Ishin came to power in 2011.

Statistically speaking, the level of per capita expenditures in Osaka City is attributable to the high level of welfare and other assistance costs. If small government is taken to mean the absolute size of government spending, then criticizing Osaka Ishin’s fiscal management with respect to small government goes against the facts.

・Balanced public finances, personnel costs, private sector utilization

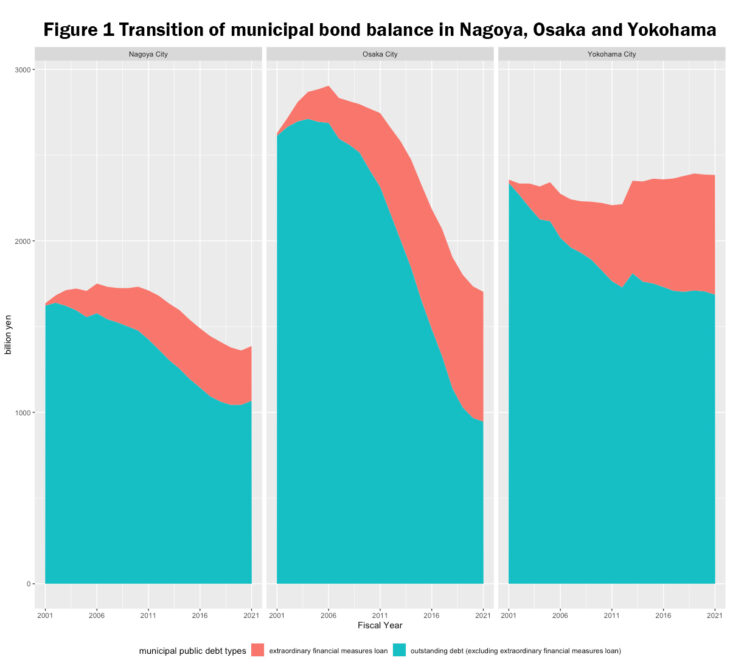

Osaka Ishin’s fiscal management of Osaka City is of a balanced fiscal character. This can be seen in Figure 1, which shows changes in the municipal bond balance of the three cities of Osaka, Nagoya, and Yokohama. Osaka City’s municipal bond balance, excluding the extraordinary financial measures loan, exceeded 2.5 trillion yen in the first half of the 2000s, making it larger than for Nagoya City and Yokohama City by a considerable margin.

The peak of municipal bonds has passed and gradually subsided since fiscal year 2011, but the sharp decline after FY2011 when an Osaka Ishin leader was appointed is noteworthy. The municipal bond balance for FY2021 was less than 1 trillion yen, the smallest amount among the three cities compared. Moreover, the total amount of temporary fiscal measure bonds is likewise shrinking, with the current municipal bond balance in Osaka City being very small compared to the past as well as to other cities. This is due to the restrained issuance of new bonds and an increase in municipal bond redemptions. Since Osaka Ishin came to power, there has been criticism of large-scale development projects such as Expo 2025 and IR (integrated resorts including casinos), but there is nothing to suggest that debts have been accruing in ordinary accounting.

Since FY2011, municipal bond repayments have remained relatively high in terms of expenditure compared to other cities, while personnel costs have declined sharply. As public service organizations are considered part of vested interests, the number of employees shrinks and salaries are revised, with the effect that the personnel costs, which used to have a deviation value of nearly 75, declined sharply and had dropped to 60 as of FY2018.

Attacks on public service organizations were also directed at extra-corporations, which have underpinned the breadth of public service work in a broad sense. The various extra-corporations associated with public service organizations were abruptly scaled back amid criticism of them being a hotbed of vested interests. According to data from Osaka City, the number of organizations was reduced from 146 in 2005 to 15 in 2021 as a result of the extra-corporations reform.[vi] In terms of financial ties with these external organizations, the structural changes in commission expenses have been emblematic. A comparison of the composition of commission expenses in FY2009 (before the Osaka Ishin administration) and FY2016 (Osaka Ishin administration) shows that the ratio of foundations and non-profit corporations decreased, with more commissions coming from commercial companies such as joint-stock companies.

Source: Created by the author based on “Local Finance Survey (for municipalities)” (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications), “Current status of municipal bonds” (government statistics site e-Stat)

・Changes in the structure of education finances

While expenditures themselves have not declined under the Osaka Ishin administration, as already mentioned, certain compositional changes have taken place. Let us take a look at education expenses, which Osaka Ishin also highlighted in nationwide local elections to see how the city’s finances have changed.

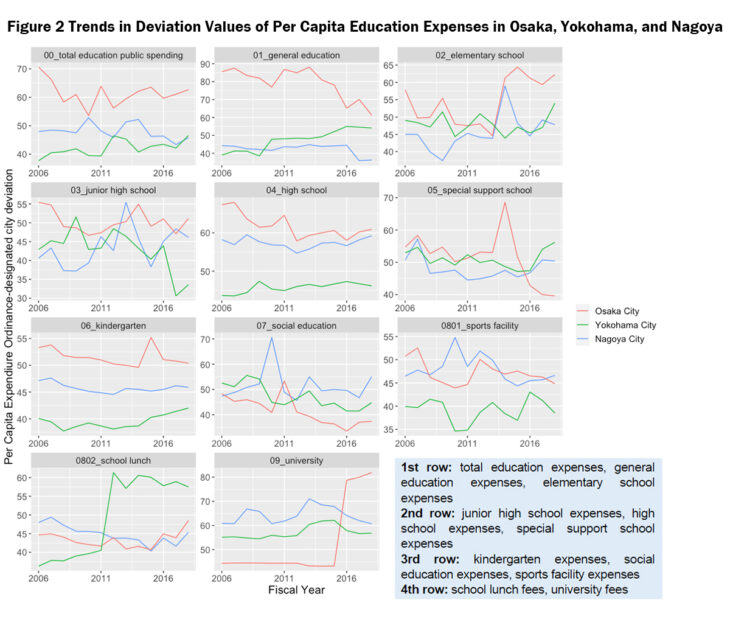

Note: For special support school expenses, the financial figures that have been recorded as special school expenses until 2012 are used.

Source: Created by the author based on “Survey on Local Public Finance (Municipal)” “Breakdown of Expenditure and Breakdown of Financial Resources (Part 5)” (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications) and “Survey on Population, Demographics and Number of Households Based on the Basic Resident Register” (Government Statistics Site e-Stat)

Figure 2 shows the deviation values for municipality education expenses per capita in the three ordinance-designated cities of Osaka, Yokohama, and Nagoya. Osaka City’s per capita education expenses are consistently higher than the average (deviation value of 50), both before and after the Osaka Ishin administration. However, as with spending as a whole, the contents of the expenses have been changing.

It can be seen that Osaka City’s general education expenses (operating expenses for the board of education, etc.) have been going down since 2011 when the Osaka Ishin administration was established. Moreover, it is not just education general affairs costs that have fallen. Since FY2014, spending on special support schools, which take in children with developmental and physical disabilities, has plummeted. Under the slogan of eliminating double administration in the Osaka Metropolis Plan, Osaka City decided in FY2014 that two special support schools would be transferred to Osaka Prefecture, a decision which was implemented in FY2016. For this reason, special support school expenses in Osaka City have been zero since FY2016.

It is usually mandatory for prefectures to establish special support schools (Article 80 of the School Education Law). However, on the basis of Article 4 of the School Education Law, ordinance-designated cities can establish such schools following an application to the prefectural boards of education. In FY2017, the authority over prefecturally funded teachers at special support schools in ordinance-designated cities was transferred to the ordinance-designated cities themselves, moving it closer to the citizens. The reforms related to the Osaka Metropolis Plan in Osaka Prefecture and City have moved in an opposite vector from this nationwide trend.

Osaka’s per capita education expenses are certainly higher than those of other ordinance-designated cities. At the same time, their actual condition has arguably changed against the backdrop of the Osaka Metropolis Plan since Osaka Ishin came to power.[vii]

All the while emphasizing global interests in city finances, special support schools and other specific administrative needs have been termed “double administration” and transferred to Osaka Prefecture, which has to meet the needs of more residents. This has been an emblematic characteristic of Osaka Ishin’s policy management.

Osaka Ishin has declared its reform policies by criticizing the various administrative needs and spending contents accumulated by administrative organizations as the vested interests of “certain people.” Arguably, this feature can be seen, for example, in the aforementioned structural changes in education expenses.

The needs of certain people may appear as useless “vested interests” to those who do not have those needs. The above criticism is not unrelated to the fact that distribution based on “selectism,” meaning that services and funds are only given to those who need them, are a source of increased fiscal confidence and resistance to taxes even when it satisfies economic efficiency.[viii]

So, what does Osaka Ishin, which attacks vested interests, claim in terms of actual fiscal allocation? The key word is a kind of universalism that removes income restrictions. Let us examine this issue in the next section.

Elimination of income restrictions and universalization of services

Osaka Ishin’s centerpiece policies in the recent [April 2023] nationwide local elections have been eliminating the income restrictions on free tuition for public and private high schools in Osaka Prefecture, free tuition for Osaka Metropolitan University and its graduate schools, free childcare for children aged 0-2 in Osaka City, and subsidies for children’s cram school fees.

It is true that suspicions have been cast in the media and elsewhere on the accuracy with which Osaka Ishin and Nippon Ishin (Japan Innovation Party (JIP)[ix] advertise the results of reforms such as making education free in their political slogans. Importantly, however, Osaka Ishin has opted for direction of expanding spending by removing income restrictions when it comes to spending requirements for public services. This choice has not been passive but active enough to be clearly stated in the party’s policy line. This suggests that Osaka Ishin is not simply an advocate of “small government.”

Osaka Ishin’s talk about income restrictions mainly in relation to education expenses have not been limited to the recent unified local elections.

At the first regular meeting of the Osaka City Council on March 1, 2012, Minobe Teruo (Osaka Ishin member of the House of Representatives) proposed the removal of income restrictions in the medical cost subsidy system for children aged 3 and above as a policy for the parliamentary group. When the City Council met on November 6, 2018, Kaneko Megumi (Osaka Ishin member of Osaka City Council) referred to the need to abolish income restrictions on reductions and exemptions of childcare fees for multi-child households.

What is interesting about this universalization by removing income restrictions on public services is the stance of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), traditionally a conservative party. At a regular standing committee meeting (education and children, regular budget) (March 24) held in March 2020, Osaka Ishin and Komeito suggested that school lunch fees should be exempted without income restrictions as a COVID-19 countermeasure.

This was challenged by Nagai Keisuke, an LDP member of the Osaka City Council. Nagai expressed understanding of the need to make school lunches free for single-parent households but was critical about the need for free school lunches without income restrictions in light of the need for subsidies for small and medium-sized businesses. It is important to note that while the LDP advocated selectist benefits, a conservative political tradition, Osaka Ishin were in favor of expanded spending that involves removing income restrictions.

Although Osaka Ishin has primarily focused on child-rearing measures, it has been proactive and sharpened its agenda to eliminating income restrictions on services received by the working generation.

The reason for this is that the supporters of Osaka Ishin are thought to be numerous among residents who have newly moved to relatively high-income areas in Osaka City. Support for the Osaka Metropolis Plan was relatively high in wards with many high-income jobs. According to the analysis of Ajisaka Manabu et al., the supporters of Osaka Ishin have been living in Osaka City for a relatively short time.[x]

Considering that the recent population growth in Osaka City was caused by an “urban return” to the central wards, it can be assumed that the upper middle class is fairly supportive of Osaka Ishin.[xi] Although this was a study conducted in the United States, it showed that the upper middle class aims to reproduce into the next generation through education.[xii] However, if traditionally conservative selectist benefits and simple “small government” are implemented, the upper middle class ends up excluded from public services such as childcare, education, and nursing care due to income restrictions. Thus, the policy of removing income restrictions is meant to expand the supply of public services to the upper middle class.

It is reasonable for Osaka Ishin to advocate a removal of income restrictions for the sake of expanded public spending, albeit centered on human capital investment, while being oriented toward development and economic growth in urban centers, thereby hoping to gain support from the upper middle class. It is worth noting that Osaka Ishin’s policies have become adapted to the needs of the global urban elite.[xiii]

At the same time, as we saw in the analysis of education expenses, specific individual administrative demands such as special support schools are not emphasized because they do not match the abovementioned needs. In terms of social security, child welfare expenditures in the public welfare budget have rather declined under the Ishin administration. This can be taken as evidence that Osaka Ishin is not expanding individual administrative demands, regarding matters like poverty and social welfare, in youth policy either.

While Osaka Ishin implements universalized services, it also dismisses individual hardships and difficulties as well as historically contingent administrative demands as vested interests. This is of a rational character for the people coming to Osaka in recent times. However, even if such public finances are opted for on the basis of democratic consent, is there no problem in demolishing individual difficulties and historically contingent administrative demands, instead allocating public services in a kind of “per capita” fashion?

Osaka Ishin’s allocation design and focus of urban politics

Osaka Ishin is trying to reject the allocation structure created primarily by the existing political parties as a politics of interests, eliminate income restrictions, and change it to a universalist “distribution per capita.” What is worrying is that universalist allocation alone is not enough to correct modern economic disparities.[xiv] If the spending remains zero-sum, conditions for people with individual difficulties can deteriorate under universalist policies. An easy way to understand this if we consider the case of distributing 10 resources to five persons, either distributing them to two poor persons (selectist benefits) or distributing them to all five persons (universal benefits).

It is certainly so that the current policy management by Osaka Ishin has become an option that benefits more residents due to its universalist nature. In this regard, it is possible that support for Osaka Ishin will spread to urban areas other than Osaka and to the working child-rearing generation.

On the other hand, since Osaka Ishin’s universalism is designed on the premise of balanced public finances, it also means taking resources from those who have been allocated resources so far. Universalist allocations can paradoxically create social divisions.

If Osaka Ishin’s reform policy comes to garner support, what options should existing political parties present? It should be noted that while Osaka Ishin’s policy involves universal distribution, it neglects the adjustments needed for individual and specific fiscal demands. Public finance is essentially a mechanism to prevent people from being excluded due to their income. In this sense, public finance is also part of social common capital. If it is important to design it so that people are not excluded from society when it comes to accessing necessary goods and services, then selectist benefits are not vested interests but are precisely what is needed to complement “universalist society.”

Institutional design that allows people to be connected to society and not fear exclusion is increasingly needed in modern urban public finance.[xv] As a policy commentator, I would like to continue to pay close attention to whether Osaka Ishin will approach the dynamics of social exclusion in modern urban public finance and whether other political parties will offer alternatives.

Translated from Kensho Osaka Ishin no kai no Zaisei Un-ei (An Examination of Osaka Ishin’s Fiscal Management: Social divisions concealed by universalism),” Sekai, June 2023, pp. 49-56. (Courtesy of Iwanami Shoten, Publishers) [July 2023]

Keywords

- Yoshihiro Kensuke

- Faculty of Economics

- Momoyama Gakuin University

- Osaka Restoration Association

- Osaka Ishin no kai

- Osaka Ishin

- Osaka Prefecture

- Osaka City

- elections

- Osaka Metropolis Plan

- government spending

- public finances

- local finances

- Hashimoto Toru

- Yoshimura Hirofumi

- Yokoyama Hideyuki

- municipal bonds

- public services

- extra-corporations

- education expenses

- special support schools

- selectism

- universalism

- income restrictions

- free tuition

- childcare

- institutional design

- social exclusion