What Emerges from a Comparison with the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France: Is the Japanese Bureaucracy of Lackey-Type Relations, Infinite Range of Work, and Posting without Application Sustainable?

“After the revision of the National Public Service Act in 2014, the [Japanese] bureaucracy has been required to uphold “lackey-type relations” (high policy involvement, low autonomy) by devoting themselves to realizing the policies aimed for by the Prime Minister’s Office.” The Diet and the LDP HQ are the main places where senior officials are busy about.

Shimada-Logie Hiroko, Professor, School of Government, Kyoto University

In many countries since the 19th century, success stories have been sought from other countries whenever dissatisfaction with their own bureaucracy grows. During the Heisei reforms of the civil service system in Japan, which ended in the centralization of executive personnel affairs, there were frequent references to models in other countries to be emulated, like “In the United States, you can come and go freely through the revolving door between the public and private sectors” and “Politicians can freely replace executive bureaucrats in Germany and France.”

However, if we are to design a bureaucracy that functions in our society, it is necessary, before importing pieces from other countries, to delve into questions like “What role do we want bureaucrats to play in relation to politics?” and “Can we secure the desired human resources in the labor market, competing against the private sector?”. In fact, the National Public Service Act, which was enacted after the United States model in the immediate postwar period, was based on naïve assumptions about the role of bureaucrats peculiar to the United States and about a highly fluid labor market and that they could be applied in Japan. Naturally, the personnel management of individual ministries came to diverge greatly from the law.

I worked for thirty-three years as a civil servant specializing in personnel systems, experiencing the inner workings of domestic and foreign bureaucracies, and have since been engaged in comparative bureaucracy research at a university. In this article, I would like to review the bureaucracy systems in the four countries of the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France, which I also covered in my book Shokugyo toshite no Kanryo (The Civil Service as Profession) (Iwanami Shinsho, 2022), and consider the characteristics of Japan that emerge through this comparison as well as their implications for the future.

The correlation between policy influence and popularity

The role that bureaucrats are expected to play in their political context varies greatly from country to country.

In continental European countries such as Germany and France, where the traditions of the royal court live on, they are expected to embody “national and public interests” beyond the political parties, which represent partial interests, so that bureaucrats are deeply involved in policymaking while maintaining autonomy. At the opposite end of the spectrum is the United States, where politicians and political appointees are responsible for policymaking, while career civil servants are, theoretically, mainly in charge of policy execution. The United Kingdom is somewhere in-between the two types, as “public interests” are meant to be judged by election results, and bureaucrats work with politicians to formulate policy but faithfully serve any government (moderate policy involvement, moderate autonomy). Until the 1960s, the Japanese bureaucracy was similar to the French and German types, but as the LDP administrations came to be firmly established, each ministry assumed a unique coordinator-type function by linking themselves with “tribe” politicians of the LDP with special-interests and actively formulating policy. Kasumigaseki came to be called the largest think tank and earned a splendid reputation overseas as well, but since the 1990s, with administrative failures and scandals occurring one after another, the vertical segmentation and bottom-up policy-making have come to be criticized as pursuits of ministerial interests without considering the nation as a whole. After the revision of the National Public Service Act in 2014, the bureaucracy has been required to uphold “lackey-type relations” (high policy involvement, low autonomy) by devoting themselves to realizing the policies aimed for by the Prime Minister’s Office.

The popularity of the civil service as a profession in a country is linked to its degree of participation in policymaking. In Germany and France, it is a popular profession reflecting its social influence. In the United Kingdom, which has undergone large-scale civil service reforms since the 1980s, the civil service is less popular than before the reforms, but there are still many applicants from prestigious universities for the Fast Stream recruitment assessment, which I will discuss later. In contrast, in the United States, ceilings of promotion and low salaries make it rare for talented students to be attracted to public service. More than 30 years ago, when I was sent by the National Personnel Authority to a British university, and identified myself as a Japanese civil servant, I was envied by my fellow German students but comforted by an American who told me, “If you work hard here, you will find a good job.”

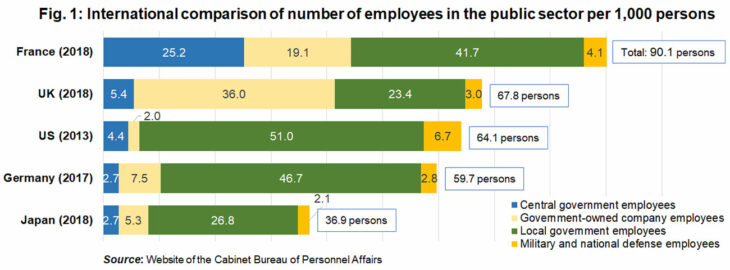

The number of Japanese civil servants (national and local) per 1,000 persons is even lower than that of the United Kingdom and the United States, both known for their preference for “small government” (Figure 1). This number includes those who are not public servants in the narrow sense, such as employees of independent administrative agencies, national university corporations, and special corporations.

The number of Japanese civil servants has been consistently low by international standards since the early postwar period. The direct reason is the upper limit imposed by the Act on Limitation on Number of Personnel of Administrative Organs enacted in 1969, but what actually made it possible was the practice of flexibly expanding the duties of individual posts without clarifying the job description. However, in recent years its limitations have been revealed, leading to stopgap by rapidly increasing the number of non-regular employees outside of the prescribed numbers.

Until the 1980s, the percentage of women among officials at the rank of director or higher at the headquarters was only a few percent in any country. This percentage came to exceed 30% in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France thanks to target plans, etc., but in Japan in FY2020, it was 6.2% for officials at the rank of director and 4.3% for designated positions (equivalent to executives of private companies).

The scope of political involvement in personnel affairs

It is common in developed countries to adopt a merit system for the hiring and appointment of career civil servants based on ability demonstrated. The principle of status security, which means that those who show good performance should not be treated disadvantageously, is also derived from this merit system. In Heisei-period Japan, some argued that “restructuring of civil servants can be done freely by giving them basic labor rights,” but basic labor rights and status security are not related.

Moreover, in order to ensure devotion to the state throughout the bureaucrat’s life, all four countries have in common that preferential treatment can be taken away if there is a treachery such as leakage of confidential information, in exchange for sufficient retirement pensions. In Japan, there was a time when retirement benefits were more generous than those in the private sector, but retirement benefits for national public servants were reduced by more than 4 million yen on average in 2012, as a balance was struck based on rigorous public-private comparative surveys since 2008.

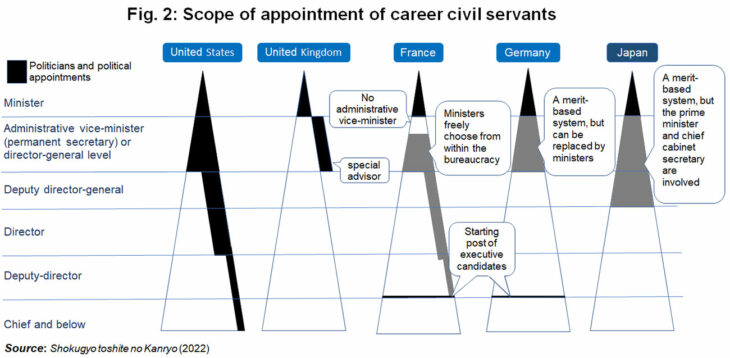

Next, let us look at the scope of appointment of career civil servants in each country (Figure 2). In the United States, all executive posts such as state secretaries and bureau chiefs as well as about 10% of directors are political appointees, leaving limited room for career civil servants to be promoted. If a president changes, political appointees are replaced at once. In the United Kingdom, the opposite is true: career civil servants occupy positions up to the permanent secretary level, and politicians are not involved in the personnel selection process. If there is a change of government, the civil service will immediately switch its loyalty to the new government. In recent years, special advisors advising on public relations and election strategy, etc. have been widely used as free appointments, but the line has been drawn so that they cannot command or order career civil servants or be involved in their personnel affairs and authorizations.

In Germany and France, unlike the United Kingdom, there is considerable leeway for ministers to have their intentions reflected in executive posts at director-general level and above. However, they are basically selected from among qualified groups of high-ranking bureaucrats, which makes the situation different from the United States.

In Germany, promotion to permanent secretary or directors-general must be merit-based, yet if a minister considers these officials untrustworthy, they can be removed. However, even if they are replaced, they will be paid more than 70% of their current salary for up to three years, meaning that double payments will be made to the old and the new executives, thus necessitating reasonable cause to satisfy public opinion.

In France, each minister can freely choose their executives and cabinet (section like the minister’s secretariat) members, but since they are temporarily dispatched from the qualified group of high-ranking bureaucrats, their original status remains secure. Movement from the government to political sphere and other sectors, including large companies, is also frequent, and the employment of bureaucrats in the private sector is called “changing from shoes to slippers” (pantouflage), which is referred to as “descending from heaven” (amakudari) in Japan.

In Japan, the personnel authority has legally vested in each minister, but actual decisions used to be left to the autonomy of the civil service of each ministry, which was close to the British model. However, after the introduction of integrated control over the appointment of senior officials in 2014, ministerial appointments at the administrative vice-minister, director-general, and deputy director-general levels are now subject to prior consultation with the Prime Minister and the Chief Cabinet Secretary. They are not political appointees per se so have remained regular positions under the merit-based principle (in contrast, the Special Advisors to the Prime Minister, the Executive Secretaries to the Prime Minister, the Cabinet Secretary for Public Affairs, the Director General of the Cabinet Legislation Bureau, and other special service positions are exempt from the merit-based principle). However, extensive political control has become easier than in the French and German systems in the sense that the guarantee of economic security after replacement does not exist.

The Japanese style of posting without application is in the minority

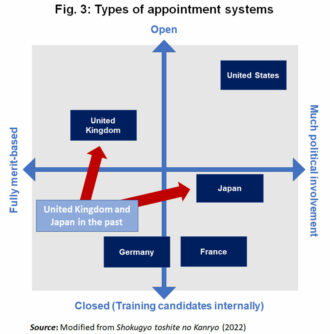

The characteristics of each country’s appointment system can be indicated by two axes: “whether there is wide political involvement or it is merit-based” and “whether it is open or closed (candidates are trained internally)” (Figure 3).

In countries where candidates are trained internally, such as Germany and France, executive candidates are often selected by specific recruitment examinations that require a high level of educational qualifications. Their first post is at the deputy director level. Those who do not belong to the group that passes this exam (Category A+ consisting of ENA [École Nationale d’Administration] graduates, etc. in France, high-grade Laufbahn consisting of mainly lawyers in Germany) run into an early ceiling for promotion, no matter how well they perform at work. Those who pass the particular exam achieve high social prestige, and competition for the exam is fierce. However, as seen in the recent “Yellow vests protests” (Mouvement des gilets jaunes), opposition to elite monopolization has increased in France, and since 2022, ENA has been replaced by INSP (Institut National du Service Public), which is declared to be less exclusive and less closed.

The opposite is true in the United States, where most posts other than political appointments can be applied for from outside. It is an open system designed to employ ready-to-work applicants by checking that their work experience matches the post requirements. Even in the case of internal promotions, it is necessary to apply for the vacancy and beat the competition. However, the average tenure of career civil servants exceeds 10 years, so the mobility is rather low except for young employees.

In the 1990s, the United Kingdom shifted to an open system, moving away from its traditional practice to train candidates internally, but the merit system has been strictly sustained. Executive posts are also filled by advertising the requirements for competency and experience, all of which is reviewed by a selection panel to ensure fairness. There is no exclusive group for executive promotion as in Germany and France, but the Fast Stream Scheme has been maintained to attract excellent students and intensively have them gain important work experience. However, the number of hires and jobs for the Scheme has been greatly increased, thus widening the gate compared to the past.

Japan previously resembled the traditional British type, but with the introduction of integrated control over the appointment of executive officials, it has moved to the right on the horizontal axis. Candidates still tend to be trained internally, but in recent years, the number of experienced people hired, as well as that of fixed-term appointments, has increased to some extent, causing a slight upward movement along the vertical axis.

It should be noted here that regardless of whether the system is open or closed, the systems have in common in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and France that individual persons apply for the posts (excluding military personnel, etc.). The duties and ability requirements for each post are clearly stated at the time of transfer or promotion. It is quite rare internationally for the personnel affairs authorities to decide on transfers inside a black box, then notify the employees concerned of their new posts, and have them know about concrete duties only after taking over from the predecessor, as is the case in Japan.

Employees are free to move out from public service in the United States, but there are certain ex-post restrictions on conduct. In the United Kingdom, Germany, and France, an examination and approval procedure is imposed in the case of moving to a related company within a certain period of time. Japan shifted from the latter model to the American model following the 2007 reform. Studies in several countries, including the United States, have indicated that low participation in decision-making and exhaustion are the main reasons for leaving public service. In Japan, the turnover rate of employees in their 20s and 30s has risen markedly in recent years, whereas no particular changes have been observed in the numbers of German and French officials.

Why is infinite overtime work seen only in Japan?

In terms of salary, in the United States and Germany, as in Japan, labor-management negotiations and disputes are not allowed, so salaries are determined by parliament. Lower salaries than in the private sector have been a long-standing concern in the United States. In Germany, a government official’s salary is not a compensation for their labor but represents a duty of the state to support them for their devotion; retirement benefits are a pension without need for premiums. In contrast, the United Kingdom relies on labor-management negotiations and agreements similar to those in the private sector, while France does not acknowledge the right to conclude agreements but allows strikes. Since the end of last year, both countries have had large-scale strikes over pensions and other issues.

In the United Kingdom, working hours are also determined by labor-management negotiations for each ministry, but in the United States, Germany, and France, they are determined by law as in Japan. Overtime hours data have not been released, but according to employee satisfaction surveys, etc., there are no signs of rampant long overtime. I have analyzed the background to why only Japan has constant infinite overtime work in my last book, so let us re-examine this topic.

The first reason is that in these four countries, each post clearly indicates a job description commensurate with the prescribed working hours. If new work duties are required, there are two choices: increase the number of employees or reduce the number of existing duties. If the person in charge of a certain duty is on a long vacation, no one else will cover for them. In Japan, the range of responsibilities of individual posts is not clear, so even if new duties are added, it is customary for them to be absorbed through managerial distribution and voluntary efforts of individual employees.

The second crucial reason is the difference in time spent dealing with parliament. In the United States, which has a presidential system, no bills are submitted by the government, so the executive branch is not involved in their deliberation. In contrast, in the United Kingdom, Germany, and France, there is deliberation on bills submitted by the government, as in Japan, making it necessary to respond to written and oral questions in parliament. It is true that the burden on the sections in charge of such work has been pointed out in the United Kingdom and France, but it is not directly linked to the constant overtime work of the ministries as a whole. Regarding written questions, the deadline for answering them is relatively long and is often extendable in the United Kingdom, Germany, and France. In the United Kingdom, there is also an upper limit on the cost of writing a response (currently £850), and questions that exceed that amount can be refused a response. In the case of questions in Japan, in contrast, all members of the Diet can submit them at any time, and the recipient ministry is obliged to respond within seven days, including weekends and holidays. There is no exception even on new year consecutive holidays, etc.

The prime ministers and ministers of the United Kingdom, Germany, and France are accustomed to improvising answers to oral questions, so it is sufficient to give a few pages of pointers in advance, but in Japan, it is the bureaucracy’s responsibility to ensure that ministers, vice-ministers, and parliamentary vice-ministers can give thorough answers. Starting with receiving the outline of questions in advance, which tends to be the night before, bureaucrats prepare detailed answers for hypothetical questions word for word, arrive at the office early in the morning of the day to brief the respondents, and remain by their side during the question-and-answer session. This is repeated throughout the period when the Diet is in session. Furthermore, the custom that the preliminary examinations by the ruling party carry more weight than the Diet exists, which is not seen in other countries. Thus, explanations to and individual coordination of members of the Policy Research Council and various subcommittees of the ruling party are also important duties of senior bureaucrats. In addition, they have to respond to public hearings with the opposition parties.

In Japan, bureaucrats going back and forth like ping-pong balls building consensus among members of parliament is a familiar daily scene, but in other countries, such explanations belong to the “domain of politics” for which ministers and politicians in the government are responsible. Digitalization, awareness-raising among managers, and penalties according to overtime caps, etc. are often proposed to streamline governmental operations, but their effectiveness will be limited unless the structure under which political coordination behind the scenes is casually left to bureaucrats is changed.

There are also variations from country to country when it comes to power harassment (bullying) countermeasures at government offices. In Japan, politicians are exempt from regulation, and some politicians boast that scolding bureaucrats is a sign of democracy. In the United Kingdom, the obligation to treat bureaucrats professionally with consideration and respect is clearly stated in the Ministerial Code. In 2020, the permanent secretary of the Home Office resigned in protest of repeated bullying by the minister of their subordinates, raising controversy about whether the Code had been violated. An investigation is also currently underway following allegations of the justice secretary’s aggressive and abusive attitude.

Remonstrations lost due to deference

In the early 2000s, I was seconded to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Permanent Mission of Japan to the International Organizations in Geneva, where I was responsible for lobbying various international organizations to recruit and promote Japanese staff. What I noticed was that even in open-call personnel management, chemistry with superiors and colleagues is prioritized, with public advertisements being issued with specific acquaintances in mind.

As such, the promoting party negotiates with the organization to ensure that the competence and experience requirements described suit a certain candidate of their own country. However, if you suggest, “This post will have a Japanese boss, so how about adding a requirement to have Japanese-language competency to communicate smoothly,” the other party will say, “It sounds as if you are declaring that there is a problem with the boss’s official language skills,” then you have no choice but to back down. On the other hand, once when a candidate from another country was selected instead of a fully competent and interviewed candidate from Japan, I asked why they failed and was told, “They were judged to be incompetent because they humbly declared that they feel overwhelmed by the heavy responsibility.” Like this, with personnel affairs that disclose requirements for each post, it is the responsibility of the authorities on every occasion to explain the reasons for their decision in detail and be convincing.

The Japanese practice of not specifying post requirements has the effect of keeping down new hires as tasks are assigned flexibly, while making the discretion of those with personnel appointment authority enormous. The same is likely true for private companies. When personnel affairs control is in the hands of authorities with no obligation to explain their decisions, employees will tend to avoid any behavior that is likely to cause displeasure from the authority. An often expressed criticism is that “The civil service reforms have resulted in excessive deference by bureaucrats vis-à-vis the Prime Minister’s Office,” but deference to superiors was strong even before the reforms.

In the United Kingdom, there is a tradition that “good bureaucrats speak unpleasant truths to power,” which is ensured by the principle of non-intervention in personnel affairs by politicians. German officials also have an obligation to give advice to their superiors. If you believe an order is illegal, you must challenge it, and if you obey an order without consideration, you are fully responsible for that on an individual level. It is even statutory that if you obey an order that harms human dignity, you will not be exempted from blame. What the two countries have in common is the idea that it is in the national interest to encourage rational remonstration from subordinates.

The thought of “resources obtained in the market”

While Japan’s reforms have regarded political control over the civil service as a panacea, in Singapore, often cited as an example of thorough meritocracy, the salary level of senior bureaucrats is comparable to that of top businessmen. Researchers have suggested that this is reflective of the thought of Wang Anshi (1021–1086), who carried out political reforms in the Northern Song dynasty in the 11th century, namely that of “compensating for the loss caused by being called upon for public service.” This philosophy, which regards bureaucrats as human resources available in the market, also highlights the importance of the perspective of resource utilization, such as what can be offered to creative talents alternatively if high salaries are difficult, as well as how to free them from behind-the-scenes political coordination duties to enable them to make full use of their policy-making capabilities.

Every bureaucracy has advantages and disadvantages. The biggest suggestion that can be gleaned from comparisons with other countries may be that the Japanese demand for “bureaucrats with top-level abilities, average salaries, infinite work duties, and who work obediently until the results politics desires are achieved” is a simultaneous equation that cannot be solved without giving up something.

Translated from “Bei/Ei/Dku/Futsu tono hikakukara ukabi agarumono: Kashin-gata, Muteiryo, Jinji-ichinin no Nihongata wa ijikano ka (Tokushu Kanryo no Botsuraku) (What Emerges from a Comparison with the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France: Is the Japanese Approach of Lackey-Type Relations, Infinite Range of Work, and Posting without Application Sustainable?),” Chuokoron, May 2023, pp. 58-65. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [June 2023]

Keywords

- Shimada-Logie Hiroko

- School of Government

- Kyoto University

- Shokugyo toshite no Kanryo (Bureaucrat as a Profession)

- bureaucracy

- civil service

- public service

- personnel affairs

- bureaucrats

- civil servant

- policy influence

- policymaking

- politicians

- labor market

- public interest

- qualifications

- merit system

- transfer

- promotion

- salary

- working hours

- overtime work

- pensions