Today’s Politics Belongs to a Limited Number of “Strong People”

“It is hoped that the barriers that make it difficult for women to enter the political world will be removed, public opinion will begin to welcome female members of parliament, and as a result, more female members of parliament will be born than the target number and play an active role.” Furthermore, clarifying the reasons why there are so few women in parliament will lead to uncovering not only the gender gap but also the fundamental problems facing Japanese politics.

Photo: sayu / PIXTA

The percentage of female Diet members in Japan is 10.0% in the Lower House and 26.0% in the Upper House. The figures for the Lower House are particularly low, ranking 165th out of 190 countries in the world (all figures are from the Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office, April 11, FY2023). What does it show that there are still fewer women? We will take a closer look at the current situation where people are loudly calling for the elimination of the gender gap, and expose the real problems.

Miura Mari, Professor, Sophia University

How do we view the gender gap in politics?

Various reports and indicators indicate that Japan has a large gender gap, so there is no need to explain it again. The political realm plays an important role in bridging this gap. The Diet creates laws and allocates budgets, and local assemblies are also involved in various policies, so if politics functions in a healthy manner, it will become a driving force for solving social problems such as the gender gap.

However, the big problem is that the gender gap remains strong even in the political realm. Because politics is not playing an adequate role, solutions to the gender gap in other areas are also far away. In other words, when considering the issue of the gender gap, we must first discuss current Japanese politics.

To measure the extent of the gender gap that exists in a country’s politics, it is common to check the gender ratio of members of parliament and cabinet members. However, politics is all about power, and whether male and female members have equal influence and voice is also an important factor. For example, even if the number of female members increases, if they all remain in low positions or speak less frequently in parliament, they cannot be said to be equal to male members. In other words, we must first understand that when it comes to gender gaps in the political realm, we need to focus on two points: numbers and positions of power. Japan has problems with both of these factors.

Considering why there are so few female politicians in Japan, the world of politics may not seem very appealing to women, and it may be difficult for them to have the desire to jump into it. However, it would be premature to conclude that the “lack of motivation” mentioned here is solely the responsibility of women, because it [lack of motivation] is likely a product of an already existing gender gap. If this is the case, we must above all change the political structure that makes it difficult for women to have motivation for politics.

So what exactly is that structure? In Japanese general companies, people who devote themselves fully to work at the expense of their personal lives are often praised. This tendency is even more obvious in the world of politics, especially since we don’t know when the Lower House will be dissolved and an election will be held, so there is no time to relax. Even if you win the election, you will be exposed to political battles over who will take what position next. Furthermore, political power is directly linked to politicians meeting as many people as possible and expanding their networks, so no matter how much time they devote to political activities, it is never enough. In that sense, it is a very demanding job, and there are only a limited number of people who can handle such long and demanding activities.

To put it more simply, “strong people” who are able to delegate all household chores such as preparing dinner and doing the laundry to others while focusing 100% on their work are more likely to survive as politicians. As you all know, the reality is that in Japanese society, there are still more men than women who are such “strong people.”

Furthermore, in today’s Japanese society, there are some people who have difficulty running for office because they have “care responsibilities,” meaning they have family members who require care, such as children, people with disabilities, or people in need of care. During the election period, candidates are expected to not only be at the microphone every day from 8 am to 8 pm [on the street or in their cars], but also to give speeches on the streets, even in the rain. If they become unwell, it will have a huge impact on the families who need their care. For them, who are always thinking about their families, it is difficult for them to devote themselves to election activities under the current system. However, if those with “care responsibility” distance themselves from the political world, the various forms of care that exist in society will become even more invisible, and problem-solving will only become further away.

Politics is essentially about debating in the Diet and passing budgets in order to help people who are in a weak social position or have difficulty living. However, it has become more common for politicians to receive generous care from someone and concentrate on political activities. If they do that, they may not be able to fully understand the situation and feelings of the so-called weak. That’s probably why we sometimes pursue “cutting off” policies. As a result, many people sigh that politicians do not understand the reality of their lives, and they stop voting. In this way, a vicious cycle is created in which people who want to continue holding power remain in the political world, and in other words, “political poverty” is becoming more and more serious in Japan.

What can be seen from the lack of women

As mentioned above, pursuing the reasons why there are so few female politicians in Japan not only reveals the reality of the gender gap that we face, but also brings to light the fundamental problems facing Japanese politics. In the current system, those who aspire to become politicians are limited, and those who simply do not want to give up power continue to remain in politics. This means that when addressing the gender gap in politics, we also need to discuss and resolve the contradictions and problems embedded in Japanese democracy.

What we must keep in mind here is that if the aim is simply to increase the number of female members of parliament, we will only be sending “strong women” into the political world who can survive within the current political system. If this happens, it will not lead to helping vulnerable people, and thus politics will not change.

Family issues can also be pointed out as the reason why it is difficult for women to get involved in politics. This is because current election campaigns in Japan require the help of people around them, and for this reason many candidates rely on the support of their families. In particular, “politicians’ wives” play a major role. The wives of male candidates organize women’s support networks. If an incumbent male MP is busy in Nagatacho (the center of Japanese politics), his wife will dedicate herself in maintaining his support organizations and running the electoral campaign in his home district. However, for a female candidate, if her husband works for a company, it is unlikely that he will be involved. Furthermore, in the old-fashioned world of politics, the image of female candidates, or wives, receiving devoted support from their husbands may even harm the image of some conservative people. In short, the current state of Japanese elections is that men’s families are used politically as a “resource.” On the other hand, if you are taking care of your own family, you can say that you are at a disadvantage [to be a candidate].

Additionally, in the Upper House by-election held in October of this year (2023), a single male candidate ran from Tokushima-Kochi at-large district [in the Shikoku region]. Although he lost the election, I saw reports among local voters saying things like, “I wish the candidate had a wife.” The current electoral system puts not only women at a disadvantage, but also single men.

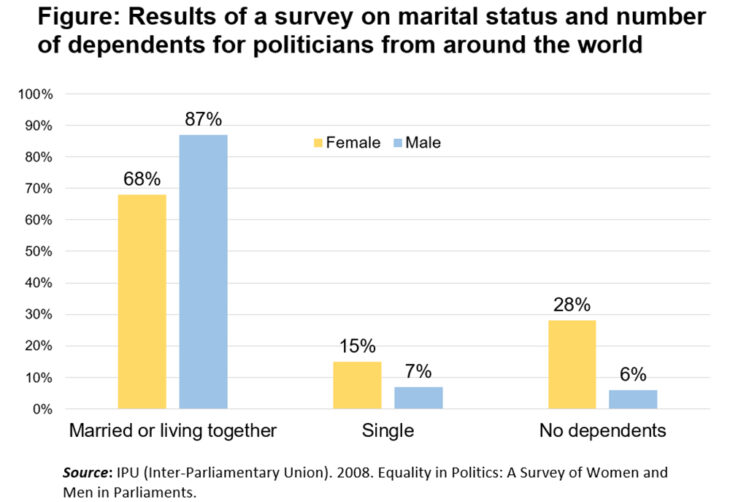

Statistics show that a high percentage of male politicians are married and have children, while there are not many female politicians who are single or married but have children (see figure). This cannot guarantee the diversity of members of the Diet. For example, if you can’t get the support of your family in your election campaign, shouldn’t society as a whole consider new options, such as building a stronger team of supporters?

Humans are essentially living creatures that require care from birth to old age. Being loved and cared for by someone gives you the foundation to lead your life with confidence. Also, loving and caring for someone leads to a meaningful life. However, if we look around society, there are many people who do not receive enough care. The role of politics is to build social support for such issues. If that is the case, there should be people from a variety of backgrounds and positions on the political side as well. The “poverty of politics” will not be immediately resolved by increasing the number of women in parliament, and the opinions of diverse men are also needed. We need a system that allows both men and women to participate in politics, including those with disabilities and those with extensive experience in care work.

Things that reduce women’s motivation

When we consider the factors that hinder women’s political participation, there is no end to the details. For example, at the Lower House, the women’s restroom is far from the assembly hall, and some have complained that it is a burden to commute there and back during breaks. In addition, the National Diet is constantly being filmed by television, and even the legs are always visible. No one would care if a man relaxed a little and spread his legs. But women can’t do that. I heard that some local assemblies have strange dress codes. For example, capri pants or cropped pants are prohibited. The rules and customs are probably based on the idea that it is disrespectful for men to show their ankles, but this does not apply to women.

The above may seem like “trivial matters,” especially to male readers. However, from a women’s perspective, they are forced to face the reality that rules are created without even assuming that women exist. Because of these things, women end up feeling “unwelcome” in politics.

Perhaps even more blatant is harassment. In the case of a woman, she is often told things like “she got the vote because she’s beautiful” or “she doesn’t get the vote because she’s a woman.” Furthermore, when women are actively involved in political activities, they are sometimes criticized out of place, asking, “Who is taking care of your children?” It would be extremely rare for a similar criticism to be leveled at men. In other words, female members of parliament are not seen as “politicians” but as mothers and sometimes as sexual objects. Many female politicians feel that they are not expected to be politicians because of such views and comments.

Countries after introduction of quota system

As I said earlier, politics is nothing but a struggle for power. In today’s Japanese society, men still hold power in many situations. Although it is difficult for women to survive in such a situation, local assemblies require fewer votes than national elections, so it is relatively easy to win. In this sense, local assemblies may be able to find hope for political activities while distancing themselves from traditional powers.

In fact, in Tokyo’s ward assemblies, it is now commonplace for 30–50% of the members to be women. In the future, the trend of women with a sense of mission running for office in local government elections will accelerate. Many women won top positions in the unified local elections held in April 2023, and considering this situation, voters should also be demanding changes to existing politics.

Recently, the “quota system” has appeared on the agenda as a means to achieve gender parity in parliaments. The quota system has now been introduced in 137 countries, and some people may be surprised that this number is unexpectedly high. According to the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), the average percentage of women in lower houses in countries with quota systems is 30.9%, and in countries without, it is 21.2%, and there is a big difference between the two. This means that the quota system is effective.

In Japan, many people may have the impression that quota systems are coercive. In reality, however, there are differences in the way a quota system is combined with the electoral system and the degree of coercive power depending on the country that has adopted it. Therefore, Japan should also discuss the issue in accordance with its own history and environment. For example, Taiwan has a quota system with a history of nearly 80 years and is currently introducing a 50% quota system for proportional representation. Moreover, women are actively represented in single-seat constituencies, and the percentage of women in the members of the Legislative Yuan (members of the Diet) is over 40%.

What you need to be careful about is that even if you introduce a quota system, it can create backlash and form a new “glass ceiling.” Along with its introduction, it is important to sustain the momentum for women’s political participation. The quota system will change the way candidates are selected, and of course the number of women will increase, but by creating more diversity among male candidates, trust in the quota system will improve.

In other words, the key to the quota system is to design an effective system and create an environment that makes it easy for female politicians to participate. It is wrong to view the argument as about whether there should be a quota system or an environment improvement. Environmental preparation is of course necessary, and the quota system is used to accelerate the preparation of the environment.

It is hoped that the barriers that make it difficult for women to enter the political world will be removed, public opinion will begin to welcome female members of parliament, and as a result, more female members of parliament will be born than the target number and play an active role. On the other hand, if the sole aim is to increase the number of women in parliament, the prejudice that “many incompetent women have entered the political world” will become stronger. It will also be difficult for female members of parliament to exercise their power, and as a result, the quota system may be adversely affected. Japan has not introduced quotas, but the “Gender Parity Law (Act on Promotion of Gender Equality in the Political Field)” was enacted in 2018 and revised in 2021. What is noteworthy is Article 2, “making the numbers of male and female candidates as even as possible,” which states that the goal is “equal numbers of men and women.”

Additionally, in the past, the number of female candidates for national elections was rarely reported, but now the number of female candidates for each party is published on the front page of newspapers on the first day of the electoral campaigning period. This is evidence that the gender gap in politics has become a matter of public concern, and being able to compare the ratio of men and women at a glance can be helpful for voters when voting. The media can also ask political parties, “Why does your party have so few female candidates?” Each political party will be under considerable pressure.

The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) currently has a numerical target of having 30% of MPs be women by 2030. This can be considered a major change. It is also important that measures to support female candidates have been expanded in order to achieve numerical targets. However, in reality, branch federations in each prefecture often decide on candidates, so whether they can steadily implement the goals set by the party headquarters is another matter. Still, I feel that a change in consciousness within the party is occurring. First of all, as voters, we need to closely monitor the progress toward achieving this goal.

How can we change the current politics?

In my personal opinion, one way to correct gender disparity in politics is to set a term limit, in addition to the quota system. Looking at examples from other countries, data shows that the number of women in parliament will not increase if the pool of potential women is small. In Japan, there is very little turnover among politicians because the incumbent’s advantage is quite large, and I think this is one of the reasons why there is less interest in politics among citizens. The term limit for governors and mayors is also an issue. Power inevitably corrupts, so it is absolutely necessary to systematically guarantee periodic power alternation. The timing of shifts provides opportunities for diverse people, including women, to participate.

In Japan, the timing of various elections is not the same, but in some countries, elections are held all at once on the same day, from the national government to local governments. In some countries, even if someone resigns during the term, there is no by-election, and a pre-designated replacement serves until the end of the term. Japan holds various elections at various times, and while voters have many opportunities to express their intentions, this may also be a factor in lowering voter turnout. Even unified local elections are no longer aligned. In November 2023, Matsushita Reiko, Mayor of Musashino, Tokyo announced her intention to run to replace the former Prime Minister Kan Naoto in the next lower house election. Then, she was criticized, saying, “Are you abandoning your mayoral duties midway through your term?” If the timing of the two elections is aligned with the term of office, it will increase the chances for incumbent politicians to contest different elections.

Of course, the “next job” in this case is not limited to the world of politics. For example, after serving two terms in local assemblies, you could work for a private company or NPO, and then aim to become a head of local government or a member of the Diet. In any case, if we become a society where human resources are more mobile, there is no doubt that Japan as a whole will be energized. In Japan, not only politics but society as a whole is too rigid, and as a result, I think we are failing to draw out dynamic energy.

There is also room for a review of the operation of political party subsidy. Japan’s political party subsidy is approximately 32 billion yen, making it the largest in the world. In order for each political party to play its role as a democratic entity, the people pay an annual tax of 250 yen per person. Shouldn’t this tax be used more effectively? I think the purpose of political party subsidy is to use it not to maintain the current political system in which only a certain type of people can participate, but to reform it. For example, in France, the further the candidates’ male-female ratio deviates from 1.0, or in other words, the further away from an equal number of males and females, the subsidy is reduced based on a certain formula. France has increased the number of female candidates by gradually increasing the penalty. I think this is a system that will be helpful for Japan. I think it is necessary to introduce a similar system first, even if it is not a strict system from the beginning. It is also possible that this measure will be taken as a temporary measure for a period of 10 years. Rather than focusing on “politics and money” only when scandals break out, we should stimulate debate about the state of the system from the perspective of why people are paying so much tax to political parties.

Considering electoral system reform

Furthermore, we should also consider fundamental changes to the electoral system. Currently, the “lack of qualified personnel” has emerged as a serious problem in local assemblies, and about 30% of prefectural assemblies are elected without voting. Legislators elected without a vote do not do the important work of directly contacting voters during the election campaign to confirm and explore the direction they should take after being elected. In fact, we sometimes hear from such legislators that they don’t know what their constituents are thinking, or that they have no response, and it must be said that this is an extremely dangerous situation.

The problem is that in Japan’s current national and prefectural assembly elections, there are many single-seat electoral districts. There is a clear correlation between the district magnitude and the proportion of female members: the larger the district, the easier it is for women to run for office, and the more likely they are to win. Municipal assemblies are not divided into electoral districts and are large electoral districts, but prefectural assemblies and special large cities are able to create electoral districts, so single-seat electoral districts are usually found in rural areas with small populations. The district magnitude will need to be reviewed from the perspective of affecting the diversity of parliamentary members. In-depth discussions are needed regarding electoral system reform for prefectures and special large cities. For example, abolish single-seat constituencies and make them more than medium-seat constituencies, or at least partially introduce a proportional representation system.

In doing so, we should aim to increase voter turnout, eliminate the shortage of qualified candidates, make the composition of members more diverse, and achieve an approximately equal number of men and women. In order to achieve these goals at the same time, we need to consider what kind of system is more desirable.

In national politics, the Upper House is 26% female, which is in line with the global average. On the other hand, the figure for the Lower House has remained unchanged for a long time at around 10%. There is a growing momentum for women to participate in politics, and some women are actually aspiring to do so. However, if there are so few women in the Lower House, we have to conclude that there is a flaw in the electoral system. The factor I think is that the system recognizes the dual candidacies of single-seat constituencies and proportional representation. Because there is a system in place for those who are unsuccessful in single-seat constituencies to be reinstated with proportional representation, they are not able to take full advantage of the benefits of proportional representation. Single-seat constituencies tend to field candidates who are strong in grassroots door-to-door election campaigns, while proportional representation makes it easier to select candidates that reflect their expertise and diverse experience. There is also the idea of moving completely to proportional representation. Also, if the single-seat constituencies system is not abolished, it is possible to create a system that is better than the current one, such as abolishing the dual candidacy system with proportional representation, or changing to a mixed system like Germany.

If reforming the electoral system would take too long, one could consider creating a “practice” of not listing dual candidates at the top of the proportional representation list; in other words, giving priority to candidates who do not run in single constituencies. The prime minister is de-facto given the right to dissolve the Diet at any time. If such a practice gains legitimacy, why not ensure the diversity of candidates by nominating women and minorities at the top of the list for proportional representation? It is not a far-fetched idea for our society to have such practices.

Eliminating the gender gap will be a major breakthrough in cracking the current power structure. As stated in this article, there are many measures to achieve this. I believe that thorough consideration by society as a whole will bring us a better future.

Translated from “Imano Seiji wa Kagirareta ‘Tsuyoi hito’ no mono (Today’s Politics Belongs to a Limited Number of ‘Strong People’),” Voice, January 2024, pp. 132–141. (Courtesy of PHP Institute) [February 2024]

Keywords

- Miura Mari

- Sophia University

- female politicians

- gender gap

- gender ratio

- gender equality

- Japanese politics

- “strong people”

- Diet members

- Cabinet members

- Upper House

- Lower House

- political structure

- care responsibilities

- marital status

- number of dependents

- discrimination

- harrassment

- quota system

- electoral system reform