Japan as a Society Dependent on Convenience StoresIs Survival without Convenience Stores Impossible in the Era of Super-Aging?

TAKEMOTO Ryota, Vice Senior Researcher, Investment Research Department II, Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Research Institute Co., Ltd.

Buying goods from foodstuffs to daily necessities at a convenience store close to our home seems a matter of course when we get used to living in an urban area. In reality, however, “people with a shopping handicap” who experience inconveniences in day-to-day shopping are growing in

population segments centered on elderly persons. According to the Report by the Study Group on the Role of Distribution Systems in Community Infrastructure put together in 2010 by a research team at the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, there were about 6 million people with a shopping handicap aged 60 or older across Japan. These persons lived primarily in two areas – rural districts where depopulation has advanced and the outskirts of urban communities where former “new towns” and the like are located.

According to Chokorei shakai-niokeru shokuryohin akusesu mondai (The Access Problem in the Super-Aging Society), written and edited by Yakushiji Tetsuro and published by Harvest-sha, Inc. in 2015, elderly persons 65 years of age or older who live 500 meters or more from a store selling perishables necessary for an everyday diet and who do not own an automobile, numbered 3,820,000 across Japan as of 2010. Such people accounted for 13.1% of all elderly persons in Japan. The ratio of people with a shopping handicap is particularly high in rural farming areas compared with urban districts. Their high ratio suggests many elderly persons in provincial areas experience inconveniences and difficulties with regard to shopping even when the use of automobiles is considered, in addition to going shopping on foot.

People without access to a convenience store discussed in this article are similar to the concept of people with a shopping handicap. However, they represent effects that are more extensive. The author assumes people who feel their access to a convenience store is inconvenient, particularly people who are advanced in age, to be people without access to a convenience store. Today, for good or for bad, convenience stores have outgrown their role as mere retail stores and changed their character into a social infrastructure that offers a wide range of services, including financial and administrative services. For that reason, not having access to a convenience store causes inconvenience in various everyday life scenarios besides shopping. On that point, not having access to a convenience store differs from a shopping handicap.

The lack of convenience stores is not often seriously discussed because the degree of its urgency is relatively low compared with medical treatment issues, such as the lack of hospitals and the lack of medical doctors. However, there is a good possibility for people without access to a convenience store to become a social issue that causes living standards in the broad sense of the word to decline mainly in provincial areas, where population size is small compared with urban districts and population is predicted to decrease rapidly as convenience stores rise in importance as a form of social infrastructure.

Convenience Stores as a Business Category Suited to Changes in Japanese Demographics and Household Composition

Note 1: Walking distance from a convenience store = a radius of 300 meters

Note 2: Elderly persons = persons 65 years of age or older

Source: Materials SMTRI produced on the basis of information released by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications and data obtained from the official websites of the various companies that operate convenience stores.

Image: Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha

Predicted future changes in demographics and household composition are assumed to become the main causes of the expansion in demand for convenience stores in Japan, which, in terms of aging, can be called an advanced nation in the world.

(1) Aging of elderly persons – reduction in their sphere of action

According to population projections released by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, one in every three persons living in Japan will be an elderly person aged 65 or older in 2035, which is twenty years from now. At the same time, one in every five persons in Japan is forecast to be an old-old person, 75 years of age or older. Japan is predicted to be such a super-aging society. Driving a car becomes difficult with age. Declined physical functions, related to such problems, are anticipated to restrict living areas to those surrounding the home and reduce the sphere of action.

(2) An increase in one-person households – subdivision of shopping demand

Unmarried persons are expected to grow in number from this point on, reflecting tendencies to marry late or remain single. According to household projections by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, the ratio of one-person households to all households in Japan is predicted to increase. In particular, the ratio of one-person households with an elderly member aged 65 or older in 2035 is expected to rise to 20% of all households. Single elderly persons are anticipated to grow remarkably in number from this point on. A decline in household members is assumed to cause changes, including a decline in demand for bulk buying at large supermarkets and purchase subdivision.

Note: Convenience stores covered are those operated by the following five companies: Seven-Eleven, Lawson, FamilyMart, Circle K Sunkus, and Ministop.

Source: Excerpted from the March 2012 issue of Franchise Age published by the Japan Franchise Association (JFA)

(3) An increase in two-income households – restrictions on active hours

Two-income households are growing in number with women’s increasing social participation in the background. As children on the waiting list for admission to daycare facilities have become an issue of public concern, the lifestyle of family households is assumed to shift from the previous style focused on households with a full-time homemaker to a new type centered on two-income households. An increase in two-income households is assumed to also restrict active hours. For example, members of such households are unable t

o buy things and perform administrative tasks on weekdays during the day.

The author thinks that the lifestyle changes stated above associated with aging and tendencies to live alone or have two earners in a household calls for bases for offering one-stop services that are familiar and convenient. Such a base close to home comprising a nationwide network enables elderly persons to access it easily on foot. We can easily predict the demand for convenience stores to expand, which can be visited from early in the morning until late at night as their raison d’être is around-the-clock operation.

Growing Expectations for Convenience Stores’ Roles as a Form of Social Infrastructure

Convenience store operators are expanding their operating territories continuously by introducing other types of business to their stores. For example, almost all convenience stores are now offering financial services through installed bank ATMs and living services, such as the acceptance of home delivery orders and payment service for utility bills. More and more convenience stores are also offering administrative services, such as the issuance of copies of certificates of residence and personal-seal registration certificates. (Refer to Figure 2.) Convenience store operators have also expanded and improved measures for coping with an aging population, such as a program for monitoring elderly persons on home delivery occasions based on a partnership with a local government and training for dementia advisors, and initiatives for meeting the demands of inbound tourists (foreign visitors), including the provision of public wireless LANs, and pamphlets in foreign languages.

The Japan Franchise Association (JFA), an incorporated body which companies that operate convenience stores belong to, put together the Declaration of Convenience Stores as Social Infrastructure in 2009. In this Declaration, the JFA positioned contributions to local communities in areas such as community safety and security and the revitalization of regional economies, as a common goal that members of the franchising industry would work to achieve, in addition to the reduction of the environmental load and the improvement of consumer convenience. The conversion of convenience stores into a social infrastructure is advancing beyond the framework of individual companies.

Convenience stores demonstrated the functions that they possess as a lifeline in a time of disaster, speedily providing emergency support supplies to disaster-stricken areas and offering drinking water and toilets to people stranded in inner-city areas when the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred in 2011.

Source: Materials SMTRI produced on the basis of data released by the JFA, Japan Post Holdings Co., Ltd., Japan Post Co., Ltd., and the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry

There must be various opinions regarding convenience stores assuming roles administrative offices are originally supposed to play. However, the author advances discussions in this article based on the fact that convenience stores are already beginning to gain widespread public recognition as a form of social infrastructure.

Number of Stores Continuing to Increase after Surpassing the Saturation Level

As a business category, convenience stores came into existence in Japan in the 1970s when the opening of large stores such as supermarkets was restricted through the enforcement of the Large-Scale Retail Store Act. Seven-Eleven opened its first store in Koto Ward, Tokyo, in 1974. And in 1975, Lawson set up its initial store in Toyonaka City, Osaka Prefecture. FamilyMart (a group of small Seiyu Stores that became independent as FamilyMart in 1981) opened its first experimental store in Sayama City, Saitama Prefecture in 1973.

The presence of convenience stores as a familiar type of living infrastructure is strengthening year after year. In 1994, the number of convenience stores came to 27,000 nationwide, surpassing the number of post offices. In 2008, convenience stores outnumbered gas stations, totaling 44,000 across Japan. (Refer to Figure 3.)

Note: The figure for convenience stores is the value of goods sold (excluding service sales).

Source: Materials SMTRI produced on the basis of the Current Survey of Commerce released by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry

Industry observers began to point out the market for convenience stores had reached a state of saturation around the time when their number topped 40,000. However, they are continuing to grow after passing the 50,000 mark. As of July 2015, in the latest survey point, convenience stores totaled 53,792 in Japan, according to the Preliminary Report on the Current Survey of Commerce released by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry. Compared with other retail business categories, such as department stores and supermarkets, convenience stores are expanding their market at a prominent pace. (Refer to Figure 4.)

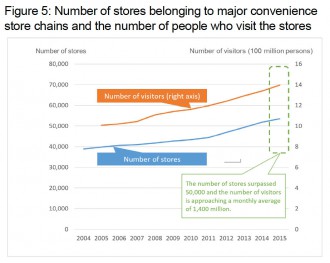

The number of customers has also been increasing with the expansion of store networks. Their number averages 1,370 million per month among ten major convenience store chains.(Refer to Figure 5.) This number includes the number of foreign visitors, but the calculation shows that each person in Japan visits convenience stores on average about 10 times a month.

Many People without Access to Convenience Stores in Provincial and Suburban Areas

Source: Materials SMTRI produced on the basis of data obtained from the official websites of the various companies that operate convenience stores

The level of inconvenience felt by people who live in an area without convenience stores near their home is feared to increase as convenience stores establish their position as an infrastructure indispensable for daily life. How large is the number of people without access to a convenience store, or how big is the number of people who live in an area without a convenience store within walking distance? Where do many of those people live?

In the following section, the author analyzes geographical relations

hips between the networks of stores operated by twelve convenience store chains (Seven-Eleven, Lawson, FamilyMart, Circle K Sunkus, Ministop, Daily Yamazaki, Seicomart, Coco Store, Three-F, Poplar, Save On, and Community Store) and residential areas (particularly those of elderly persons), and introduces findings through his study aimed at grasping the population of areas within walking distance covered by convenience store networks (the number of people who live within a certain distance from the nearest convenience store that is easily accessible on foot) and the actual conditions of people without access to a convenience store who live outside areas covered by the network of convenience store.

Looking at the breakdown of about 54,000 convenience stores in Japan as of July 2015 by prefecture, the number of stores per population is largest in Tokyo where there are 5.3 stores for each 10,000 residents. In the meantime, their number is smallest in Nara Prefecture where 3.1 stores exist per 10,000 residents. (Refer to Figure 6.) Among 1,896 municipalities in Japan, 141 did not have any store run by a convenience store chain covered in the study. The author confirmed many municipalities have three to five convenience stores by checking the numbers of stores per 10,000 residents. The tendency allows us to say convenience store operators are respectively keeping the population size of a municipality and the number of stores there in balance as a rule. Limiting the scope of examination to elderly persons aged 65 or older, many municipalities have about fifteen stores per 10,000 residents in that age group.

The distance from a given convenience store to the next closest one averages 528 meters nationwide. This figure tells us that two or more convenience stores are located in a relatively small area. The distance between the two closest convenience stores becomes 149 meters when a figure for the twenty-three wards of Tokyo is used in the calculation. It means convenience stores are located at intervals of about 150 meters. This distance reflects the level of convenience store concentration in metropolitan areas.

Source: Materials SMTRI produced on the basis of data released by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications and statistics obtained from the official websites of various companies that operate convenience stores

The author estimated the ratio of people who live within a certain distance from the nearest convenience store that is easily accessible on foot, based on the location of each convenience store and residential (nighttime) population of each meshed area 500 meters square in the 2010 census (such area 250 meters square in ordinance-designated cities as of October 2010 and the twenty-three wards of Tokyo). Walking distance is generally defined as a radius of 400 meters covered in five minutes assuming a walking speed of 80 meters per minute. Such a distance is often defined as a radius of 500 meters when an area a little broader is adopted. In this article, however, the author assumes a radius of 300 meters covered in five minutes at a walking speed of 60 meters per minute as a walking distance, taking into consideration the fact that elderly persons walk at a slower pace than young people.

In the twenty-three wards of Tokyo, 86 percent of elderly persons live within a radius of 300 meters from the nearest convenience store. In the meantime, the ratio of elderly population covered (the ratio of elderly persons who live within a 300-meter radius that offers easy access to the nearest convenience store by foot) is only 39% nationwide. In other words, about 60% of all elderly persons in Japan are assumed to be people without access to a convenience store and that makes them feel inconvenienced when walking to such a store.

The author totalized the ratio of the elderly population covered within walking distance from a convenience store by prefecture. The ratio of the population covered within a 300-meter radius was at high levels of around 60% in Osaka Prefecture and Kanagawa Prefecture that followed Tokyo in ranks. The same ratio came to about 50% in Saitama, Aichi, and Kyoto Prefectures. Elderly persons who feel their access to a convenience store is inconvenient are assumed to be relatively small in number in the three major metropolitan areas of Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka. (Refer to Figure 7.) In the meantime, the ratio of such people covered was less than 20% in Shimane, Iwate, Akita, Tottori, and Saga Prefectures. We can assume from these figures that people in provincial areas without access to a convenience store are at a serious loss just as people with a shopping handicap are in those areas.

The Number of People without Access to a Convenience Store Falls as the Population Density Rises

The author confirmed relationships between the ratio of population within walking distance covered by convenience stores (the ratio of ordinary people who live within a radius of 500 meters from the nearest convenience store that offers easy access on foot) and the average marketing area population (the population of persons who live within a radius of 500 meters from a convenience store). Through this confirmation, the author discovered a tendency for the ratio of the walking distance population covered to increase as the average marketing area population grows in size. Such a tendency was observed in all parts of Japan except metropolitan districts where the daytime population is large, such as Chiyoda Ward in Tokyo, Chuo Ward in Osaka City, and Naka Ward in Nagoya City.

The average marketing area population shows the degree of housing accumulation in areas around convenience stores. We cannot raise the ratio of population covered and reduce the number of people without access to a convenience store by simply increasing the number of convenience stores for that reason. In suburbs, compactification of residential areas through steps, such as housing accumulation around train stations, is assumed to be essential. The result can also be interpreted to mean a convenience store run by a private company is difficult to expect unless the population reaches a size that makes economic sense.

The author also confirmed relationships between the number of convenience stores per elderly population and the ratio of elderly persons covered by convenience stores prefecture by prefecture. Through the study, the author found the compactness of elderly residences and the efficiency of convenience store locations vary from one municipality to another.

For example, there are only forty-seven convenience stores in Joto Ward in Osaka City where about 41,000 elderly persons are living. The number of convenience stores per 10,000 elderly persons is 11.5 in Joto Ward, lower than the national average of 16.6. In spite of that, the ratio of people without access to a convenience store who live outside a radius of 300 meters from a convenience store was only 11% for Joto Ward. The ratio of such residents was extremely low, compared with the national average of 61%.

In addition to Joto Ward in Osaka City, areas such as Nishinari Ward in the same city can be called compact in terms of areas where elderly persons live. The ratio of population covered by convenience stores is high in these areas in spite of the small number of such stores per population. In the meantime, locations, such as Tobishima Village in Aichi Prefecture and Otoineppu Village in Hokkaido are low in the compactness of areas where elderly persons live. The ratio of population there covered by convenience stores is low even though the number

of such stores per population is large. They are municipalities where the stores appear to be unevenly located along the roadside of suburban areas.

A Manpower Shortage as a Factor Restricting the Expansion of Store Networks

We need to increase the ratio of the population within walking distance covered by convenience stores in order to make the most of such stores as a form of economic and social infrastructure in every corner of this country. In that respect, further expansion of the convenience store network is anticipated to work toward the elimination of people without access to a convenience store. As a step in that direction, the Japanese government is expected to request prefectural governments to relax restrictions in urbanization control zones where the opening of convenience stores and other commercial facilities is restricted in cases where their relaxation is necessary in order to offer shopping opportunities to local residents.

In the meantime, the Investigative Report on the Economic and Social Roles of Convenience Stores put together by a research team at the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry in March 2015 gave the strongest recognition to the “guarantee of employees” as a challenge convenience stores face in their efforts to step up or implement various new initiatives related to their economic and social roles.

Regarding reasons for a manpower shortage, we can gather the existing condition that few people can work in the certain required time zones as a problem closely connected to the convenience of operation during the late-night hours. A manpower shortage is viewed as a structural business issue partly because of the intensifying competition with food-based supermarkets and restaurants for employing students and other part-timers.

As a growing trend, companies that operate convenience stores are working to expand employment support for elderly persons in cooperation with local governments, taking steps such as the provision of job explanation sessions to elderly persons. To cite examples, Seven-Eleven is working with Fukuoka and Osaka Prefectures and Lawson is teaming up with Yokohama City in such initiatives in an attempt to secure employees. Elderly persons are also considering working at a convenience store close to home that is within easy commuting distance to match their lifestyle in their declining years.

However, the workforce will inevitably enter a declining phase in due course with the advance of aging, in other words, the further graying of elderly persons (an increase in the old-old population), under conditions where a trend toward fewer children due to a declining birthrate cannot be expected to improve. A shortage of employees will be a factor that makes the expansion of convenience store networks difficult.

People without Access to a Convenience Store are Feared to Increase More in Provincial Cities

In a society with a decreasing population attributable to the graying of the society and a low birthrate, the population is anticipated to decrease quicker in provincial areas where the population is small. In municipalities with 50,000 or less residents, the population is forecast to decline close to 30% in the period through 2040. Population is also projected to decrease about 15% in cities whose population is about 200,000 now. (Refer to Figure 8.) Convenience stores operated by private companies may be forced to withdraw from marketing areas when their population falls to a level that does not make economic sense. In other words, people without access to a convenience store are assumed likely to emerge more easily in provincial areas where the pace of population decrease is faster than in urban districts.

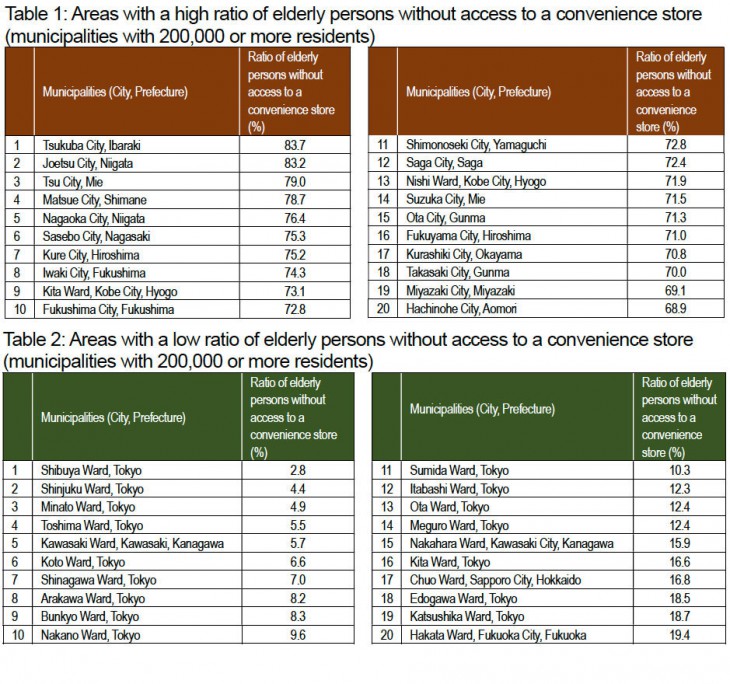

Furthermore, more than 80% of elderly persons are assumed to have already lost their access to a convenience store in Tsukuba City, in Ibaraki Prefecture, and in Joetsu City in Niigata Prefecture among municipalities where 200,000 or more people live. There are many cities with prefectural offices where the ratio of residents without access to a convenience store has surpassed 70% of their total population. Such cities include Tsu in Mie Prefecture, Matsue in Shimane Prefecture, Fukushima in Fukushima Prefecture, and Saga in Saga Prefecture. (Refer to Table 1.) In these municipalities, the population decrease is feared to cause a further increase in the number of people without access to a convenience store and accelerate a decline in their convenience of living in the future.

Note 1: Population projections are added to the populations of respective municipalities at the point of 2010.

Note 2: The population of Fukushima Prefecture is excluded from the total population because no municipal estimate is available for the prefecture.

Source: Population Projections for Japan by Prefecture (estimates in March 2013) published by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

The networks of convenience stores easily accessible on foot that can meet a wide range of living demands from the purchase of daily necessities to financial services to administrative services are anticipated to grow in importance in a super-aging society predicted to arrive in the future. In large cities such as Tokyo, people without access to a convenience store, or people who feel that their access to a convenience store is inconvenient, occupy only about 10% of the total elderly population there. However, 40% to 60% of all elderly persons are assumed to have already lost their access to a convenience store nationwide. We must prevent people from losing their access to a convenience store so that we can use convenience store networks effectively as an economic and social infrastructure in Japan where aging is advancing fast. The compactification of residential areas through the concentration of houses is assumed to hold the key to preventing the loss of access to convenience stores.

Translated from “Tokushu –Konbini Izon-shakai Nippon/ Chokoreijidai, Konbini ga nakutewa Ikiteikenai? (Feature Article – Japan as a Society Dependent on Convenience Stores / Is Survival without Convenience Stores Impossible in the Era of Super-Aging?),” Chuokoron, November 2015, pp. 84–95. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [November 2015]