Internationalization at Universities – True or FalseThe Emptiness of “Global HR Development”

The Advancing “All Japan” Initiative

YOSHIDA Aya, Professor at the Faculty of Education and Integrated Arts and Sciences, Waseda University

“Global human resources”—It’s now become a household phrase, but it wasn’t until the latter half of the 2000s that this term started to circulate frequently in society. Amidst the advancing flow of Japanese companies relocating their operations abroad, it was originally a phrase that pointed to employees who could work in locations overseas. But gradually, the “development” of these human resources came to be an issue, and attention focused on the “universities” as the place for that to happen. Then, in the blink of an eye, many Japanese universities started to raise the development of these global human resources as their mission.

The role played by the Japanese government in this process cannot be overlooked. What started it all off was the Industry-Academia Partnership for Human Resource Development, initiated by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) in 2007. The task of developing the global human resources sought by companies was imposed on the universities, and METI began considering its plan of action, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). As a result of this, new demands were issued saying that the universities should implement their own organizational reforms in line with global standards. By reference to the Times Higher Education World University Ranking (started in 2004), it was argued—based on the low number of foreign students and faculty members—that the globalization of Japanese universities was lagging behind, and so universities were told to raise their international reputations.

Logically speaking, the fostering of the global human resources demanded by Japanese companies and the universities raising their positions in the world rankings are not two things that seem directly connected. But in reality, the keyword “globalization” has a wide variety of connotations attached to it, and the reform of the universities with the aim of globalization is being driven forward on all fronts, by an “All Japan” initiative comprising government, industry and academia.

In the first place, since the time of their creation universities have been organizationally characterized by being based on the universality of scholarship, and even since being placed under the protection and control of the modern state they have not confined their education and research activities solely within the country.

However, in the case of Japan—which was slow to begin its process of modernization—the universities have been regarded as an apparatus for playing catch-up through the intake of modern Western culture, and demands have repeatedly been placed on them by the state to open up their activities.

Speaking of the period since the end of World War II, the first response was the “internationalization” of the early 1980s, and the second was the “globalization” that began from the late 2000s.

In this article, with a focus on higher education policy, we will shed light on how—by the spread of economic globalization to the universities—the perspective of internationalizing the universities as a place for international exchange has shifted in the direction of demanding their globalization as part of Japan’s domestic economic growth strategy. Additionally, we consider the problems faced by recent university reform.

From International Exchange to Global Strategy

The first “internationalization” initiative came after Japan had accomplished its rapid postwar economic growth, and had just overcome the effects of the second (1979) oil crisis.

Japan’s budding sense of confidence that it had become a nation on par with the developed nations coincided with countries such as China and Malaysia beginning to send out students to foreign countries, and efforts to try to attract overseas students began, focusing on Asian countries. This was the 100,000 Foreign Students Plan (1983), and its objective was to encourage international exchange with universities in various foreign countries while also cooperating towards the cultivation of human resources for developing countries. The language for foreign students was Japanese, and the construction of a framework for Japanese language education, both domestically and abroad, became an important policy measure. This target for the internationalization of Japan—under the self-confidence that, while until then we had just been continually sending Japanese students overseas to Europe and the United States, we had finally reached the level where we could accept foreign students—was achieved, although rather behind its original schedule, in 2003.

Efforts to attract international students also continued after that, with the formulation of the 300,000 Foreign Students Plan in 2008. However, the objective of this plan is not international exchange. Its aim is in acquiring high-caliber foreign students and having them enter employment in Japan after graduation, as part of Japan’s global strategy. “Global strategy” does not mean expanding overseas, but rather resolving Japan’s domestic issues as a country with a declining population through the cultivation of high-level human resources that will contribute to the country’s economic growth, and foreign students were chosen as a convenient means of achieving this. There was a shift in policy regarding foreign students. In order to implement this plan, the government proceeded with the selection and development of specific “hub” universities through competitive funding (the Global 30 project), and requested the establishment of degree programs where all the courses are conducted in English for students from overseas. International students who are educated in English at Japanese universities and then go on to work in Japan after graduation: they exactly the global human resources that companies are looking for.

From Foreign Students to Japanese Students

However, after that, the argument for turning foreign students coming to Japan into global human resources hasn’t manifested itself strongly. Instead, it was Japanese students that came into close-up. There are two reasons for this change.

The first reason is that, as a result of the great shock that came with the pointing out of Japanese people’s poor English ability and of the decreasing number of Japanese going to study overseas since 2004 (“introverted thinking”) in the aforementioned Industry-Academia Partnership for Human Resource Development, it turned into the argument that the globalization of Japanese students should be the first priority.

The second reason was the appearance, in connection with the first, of the argument that the national budget—under tight fiscal austerity—should be used for Japanese people rather than foreigners, and that the significance and effect of creating globalization hubs through the Global 30 project came to be viewed in a negative light.

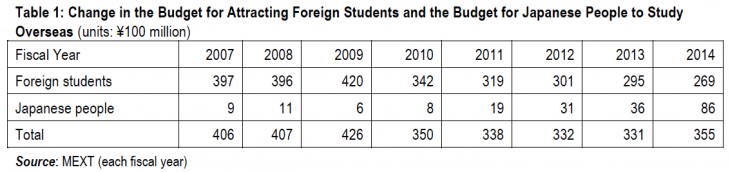

In response to this, MEXT turned their rudder towards the direction of policies for encouraging Japanese people to study abroad and developing Japanese students into global human resources. Where this is expressed most prominently is in the annual budget. Table 1 shows the budget (or proposed budget) with regard to international student exchange each year since FY2007, when they began to distinguish between the budget for attracting foreign students and that for sending Japanese students overseas. The 300,000 Foreign Students Plan established in 2008 is reflected in the sharp increase in the budget for FY2009, but prior to that too just under ¥40 billion was budgeted

each year for international student exchange. It’s not the case that the 300,000 Foreign Students Plan has ceased to exist even now and attracting foreign students remains a solid pillar of government policy. However, the budget for enticing foreign students is being reduced year by year since FY2010.

On the other hand, the budget for Japanese students to study abroad has been showing growth since FY2011. This is a response to the setting of numerical targets, such as that set out in the New Growth Strategy (June 2010 cabinet decision), to increase the number of Japanese students engaged in exchanges such as overseas study or training etc. to 300,000 people, or that set in the mid-term review by the Committee for the Promotion of Global Human Resource Development in 2011, to increase the number of Japanese people with one year or more of experience studying overseas to 80,000. Incidentally, one element contained in the definition of “global human resources” laid out by the mid-term review was “identity as a Japanese person,” from which it can be seen that the existence of foreign students is not in their field of view.

The Globalization-Reform of Universities

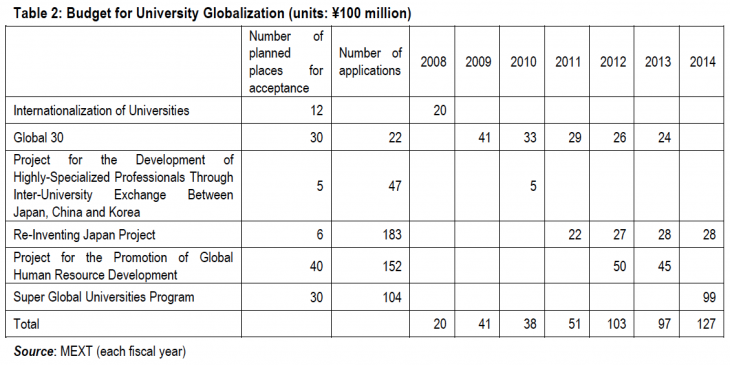

The shift in policy towards placing the emphasis on Japanese people can also be seen in the increase in the budget category called “University Globalization” (Table 2). In this category, which appeared in FY2008, the budget doubled when Global 30 began in FY2009. But in contrast to the way in which Global 30 tapers off, projects that place overseas study for Japanese people at the forefront are deployed one after another. The Re-Inventing Japan Project, established with the New Growth Strategy as its backdrop, promotes cooperation with foreign universities to establish programs for mutual credit transfer and degree awarding, and aimed to make Japanese students go to study abroad within this framework. The FY2012 Project for the Promotion of Global Human Resource Development is literally the cultivation of Japanese students into global human resources, raising the improvement of foreign language ability and the promotion of overseas study as its objectives.

Making a simple comparison from Tables 1 and 2 for FY2014: the budget for foreign students is ¥26.9 billion, while the budget for Japanese students is ¥21.3 billion (¥8.6 billion + ¥12.7 billion). The gap between the two is shrinking. We can tell that the development of Japanese people into global human resources has become an issue.

One other thing that should be pointed out in connection with the transition of these budgets is that there is a drive that is taking place to shift the emphasis away from individuals and place it on the universities. The budgets in Table 1 for attracting foreign students and for Japanese people to study overseas apply to individuals. On the other hand, the university globalization budget in Table 2 is a budget that goes to the universities, which are the bodies that actually implement these projects. If we compare these two tables, it is clear that the proportion of the budget being allocated to institutions (i.e. the universities) is increasing year by year.

Moreover, because the budget for university globalization aims to achieve the formation of hub universities, the number of planned places for each project (as indicated in Table 2) is very small. Accordingly, the budget per place is large—in the hundreds of millions of yen—and, amidst reducing annual current expenses from the MEXT, represents significant external funding for institutions which receive the budget. However, as indicated by Table 2’s surprisingly low number of applications, many universities are excluded from these projects. Amongst the five projects, the number of universities selected for one project is 63; amongst them, the number selected for three projects is 15, and the number selected for four projects is just 4. It goes without saying that these are former imperial, national universities and long-established, large-scale private universities.

The first reason that this type of situation is arising is that—due to the nature of these programs as objective-based projects—harsh prerequisites are imposed on applications, and not many universities can clear these application conditions. The second is due to the trend for universities for which the possibility of selection is high to fear that, if they do not apply, it might give the impression that they are neglecting their duties towards reform. To put it another way, there are two forces at work here: the force making some universities give up before even applying, and the force that makes other universities think that they have to apply. The distribution of competitive funding based on the principles of selection and concentration is creating competition within a limited scope, while denying a large number of universities the opportunity to participate, and making the very small number of “winners” stronger and stronger as a result.

Enhancing the International Competitiveness of the Universities

As stated in the opening paragraphs, the other task facing the universities was raising their positions in the world rankings. The consummation of this is the Top Global University Project, which began in FY2014, following the third proposal from the Council for the Implementation of Education Rebuilding. With the target of having ten universities enter the top 100 in the world rankings within the next ten years, ¥420 million of funding is to be given to around ten universities every year, out of the thirty planned places for selection. At long last, an initiative is beginning that places the task of raising universities’ positions in the rankings at the forefront, and furthermore raises numerical targets for the project. The objectives of this program are defined as raising the presence of Japanese universities in the global higher education marketplace and their ranking in on the world stage; however, being rated on par with the Western universities that occupy the top positions in the rankings is not necessarily its aim. The basis for it is the sense of impending crisis towards Asian universities raising their positions in the rankings, amidst the rapid growth of Asian economies in contrast to Japan’s economic stagnation.

So, what does a university need to do in order to become a “Super Global” university? In the application requirements, it states that a push for thorough university reform and internationalization are required in order to become one, and indicates governance reforms, educational reforms and internationalization as the course to follow. However, there is nothing exceptionally new among the numerous detailed items indicated under these headings. Rather, they seem to trace exactly over the reports of the Central Council for Education and the proposals of the Council for the Implementation of Education Rebuilding for the last few years. Will the rankings of Japan’s universities rise up by themselves if the policies of reform that have been presented until now are implemented as they are, across all universities? Also, what kind of meaning is there in setting quantitative and qualitative targets for each of them? It appears that these targets are being applied as selection criteria without even questioning why they will lead to a rise in the rankings.

For example, the ratios of foreign faculty members and international students are important indicators in the rankings. Raising these ratios is not something achieved by some haphazard strategy for acquiring foreigners, but a result of carrying out education and research that is capable of attracting them into coming. Surely the debate on how to raise th

e level of this kind of education and research comes first. And it’s good for there to be various different paths to achieving that purpose. However, as far as I can tell from looking at the application requirements, selection criteria and so on, there doesn’t appear to be much freedom for universities to devise their own, original ways of doing things. It seems that these projects for raising the international competitiveness of Japan’s universities are still being guided by the old-fashioned goso sendan “convoy” system (in which the government micromanages competition between companies or institutions in order to protect the weakest organizations).

Universities As a Place For Free Thinking

The pressing issue of developing global human resources is a demand that arose from the sense of crisis towards Japan’s declining relative economic position. It was the late 2000s when this reached the universities, but in actual fact Japan’s universities have repeated various educational reforms since the 1990s, and are still in the midst of that process. Specifically, this began with faculty teaching in teaching and learning processes. In the 2000s, the focus shifted to student learning, and the main theme in recent years has been governance reforms in order to ensure swift decision-making. The keyword for seeing these reforms through is the improvement of quality. When the cultivation of global human resources was demanded of the universities and it linked into the already progressing educational reforms, it was argued that it would not become possible to comply with the issue of human resource development or increase the level of international competitiveness until we achieved an improvement in quality through reforms. Therefore, universities must pursue both the implementation of projects through the various types of competitive funding, and educational reforms, at the same time. Since items for reform will be piled on sequentially, the selection criteria will become more and more detailed.

Incidentally, in the case that a selected university is unable to achieve its targets, then naturally that university is condemned for its over-optimism, lack of effort and so on. But who is to assess whether or not the cause of the university’s failure lay in the content of MEXT’s projects? Looking at the long list of screening categories derived from the reform policies, I think that an assessment of the suitability of those screening categories is necessary too.

Having said that, the universities too are knowingly participating in these schemes, under the understanding that the acquisition of competitive funding will rob them of a degree of freedom with regards to education and research, and in that sense they are also complicit in this crime. Also, since competitively funded projects have a strong aspect of being used as an economic tool, and results are demanded over a short period of time, there is a visible trend for universities to specialize their plans towards being able to produce immediate results. Aren’t universities abandoning the act of thinking for themselves about their own state of being and future direction? For example, the main plan in the Project for the Promotion of Global Human Resource Development comprises improving English test scores and two to three months of overseas study. I just can’t help but feel like that makes for rather stunted global human resources. The most important privilege that universities possess is the right to think freely, and we have a history dating back to ancient times of fighting to protect this freedom from those who would seek to violate it. This is because we know that the flowering of intellectual pursuits is something that is obtained out of the “soil” of free thought. It’s not the case that as long as there is freedom the flower of knowledge will always bloom, and it is also certainly true that there are many cases in which it does not. But even so, the reason we have protected that freedom is because, without it, the flower will not open. Currently, there is a strong trend towards efficiently feeding the flower chemical fertilizer and trying to make it bloom bigger and faster, but fertilizer is useless without the soil. We must not forget the act of tilling the soil of freedom.

With regard to global human resources, the human resources that universities should be cultivating are the kind of people who can work towards the various problems that are currently arising globally. There will probably be cases where it is not possible to deal with these problems with existing academic disciplines. What will then be necessary is the creation of new fields of study by the intersection and recombination of these existing disciplines, the construction of new education methods and so on. This will truly be impossible without a place for thinking freely.

Translated from “Tokushu – Daigaku-kokusaika no Kyojitsu: ‘Gurobaru Jinzai Ikusei’ no Kukyo– (Special Issue – Internationalization at Universities – True or False: The Emptiness of ‘Global HR Development’),” Chuokoron, February 2015, pp. 116–121. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [February 2015]