What is Needed for Konbini to Truly Become a Part of Social Infrastructure

Today, Japan’s convenience stores (konbini) can already be considered a form of so-called social infrastructure. However, in the face of Japan’s current social circumstances, with the decline in population size and the progression of population aging, konbini now find themselves standing at a crossroads, unable to cater to various changes in consumer lifestyles. In this article, we will consider the reasons behind this situation, and explore ways in which konbini can continue to function as a true part of social infrastructure in the future, based on the history of their evolution up until this point.

Konbini at a crossroads

Kato Naomi

Until now, konbini have been recognized/acknowledged as a part of Japan’s social infrastructure, as opposed to simply “convenient” stores at which to shop. This is due to the fact that, despite individual stores being small in scale, convenience store chains have provided not only products but also a wide range of services by establishing large presences with numerous stores connected by large-scale distribution networks, and information systems connecting individual stores to their head offices.

Now, however, konbini are standing at a major crossroads. The reason for this is that, despite expectations for them to support the lifestyles of Japanese consumers amidst social issues such as population decline and population aging, konbini have fallen into a state where they are unable to cater to changing consumer lifestyles. There are three major reasons for this.

The first is their progressive shift towards oligopoly as a form of retail category. The second is that, amidst changes in consumer shopping behavior with the advent of Internet-based society, it has become difficult to say that konbini are actually “convenient” stores. The third and final reason, and also the most serious issue, is that labor shortages are placing increasing pressure on store management.

If konbini are to continue to play active roles as a part of social infrastructure in the future, it will not be sufficient to entrust things solely to the konbini chain operators and konbini franchises themselves. It will also require the wisdom of the consumers who wish to make use of them.

Konbini as a retail category

Until now, konbini have continued to expand the scale of their sales. The number of stores is also growing. For example, as shown in Figure 1, as of February 2019 (FY2018) the number of konbini in Japan has exceeded 58,000, an increase of around 20,000 stores in comparison with just under 40,000 stores fifteen years ago.

However, although looking at the breakdown of those stores we can see that the numbers of stores operated by the three biggest chains (Seven-Eleven, FamilyMart and Lawson) have rapidly increased, growth in the number of stores operated by other companies has stagnated. In some cases, those companies have disappeared completely. Today, around 90% of konbini are accounted for by the top three companies.

Typically, a progressive shift towards oligopoly would weaken competitiveness, bringing about a decline in the industry as whole. In the retail industry, there is fierce competition between business categories, and there has been a repetitive cycle of existing business categories falling into decline and new business categories emerging. Currently, the category displaying the most significant growth is the electronic commerce (e-commerce) category, while categories that stand out as being in obvious decline are department stores, gross merchandise sales and other retail formats based on large-scale commercial facilities such as shopping malls.

Of course, although the konbini category has developed into an oligopoly, the category itself is not yet in decline. However, from a consumer perspective, it is an undeniable fact that the number of possible options when it comes to konbini has decreased due to oligopoly.

From the latter half of the 1980s into the early 1990s, when konbini came to be accepted as “convenient stores,” there were over fifty convenience store chains in Japan, even counting only the main ones. For example, people living in the Greater Tokyo Area can probably remember AM/PM. People from the Nagoya area will remember chains such as Circle K and Cocostore, and those from northern Kanto can probably remember Save On. Some people might also remember the international voluntary chain SPAR. Each of these companies established unique and individualistic konbini chains.

So what is the difference between these other chains that eventually disappeared and the current three major chains? Frankly put, it is the difference in financial power (including royalties from franchise stores) amassed at each chain’s headquarters. The development of stores, products and services, as well as information and logistics systems, is all carried out at head office. The more capital is amassed at a chain’s headquarters, the more powerful the force driving the chain and its stores.

During the 1980s, the number of young people living alone increased, primarily in city/urban areas. Convenience stores appealed to their stomachs with bento lunch boxes, onigiri (rice balls), ready-to-eat dishes and other products that could be eaten immediately after purchase; and supported their lifestyles in other aspects by selling advance tickets for movies and shows, and payment agency services for utility bills.

Moving into the 1990s, konbini continued to grow, even in spite of the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy. The various chains developed larger presences with numerous stores, seeking to become the closest and most familiar store for consumers, and making effective use of information and logistics services to identify and provide the kinds of products and services needed by consumers. Although until that time konbini had often been characterized as stores for young people, they now began to gradually expand their customer demographics to include housewives and senior citizens. Many consumers managed to find the products they needed at konbini, and began to enjoy the convenience of shopping at them.

However, the concept of convenience has changed with the times. In today’s Internet-based society, we can sometimes hear people say things like, “Eh? You’re going to go all the way to the konbini?” There are now many services that can be handled and products that can be ordered simply by using a smartphone, in the very palms of our hands. For people who make convenient use of online services, even making a trip to a konbini (even when it is very close nearby) can feel laborious. Moving forward, not only smartphones but also smart speakers, IoT appliances and various other devices (including those to emerge in the future) may actually come to perform social infrastructure functions in the place of konbini.

In other words, the number of consumers who cannot be satisfied by the kind of “convenience” offered by konbini until now will continue to grow. At the same time, konbini are not managing to offer new forms of convenience that cater to changes in people’s lifestyles.

Konbini from a franchise perspective

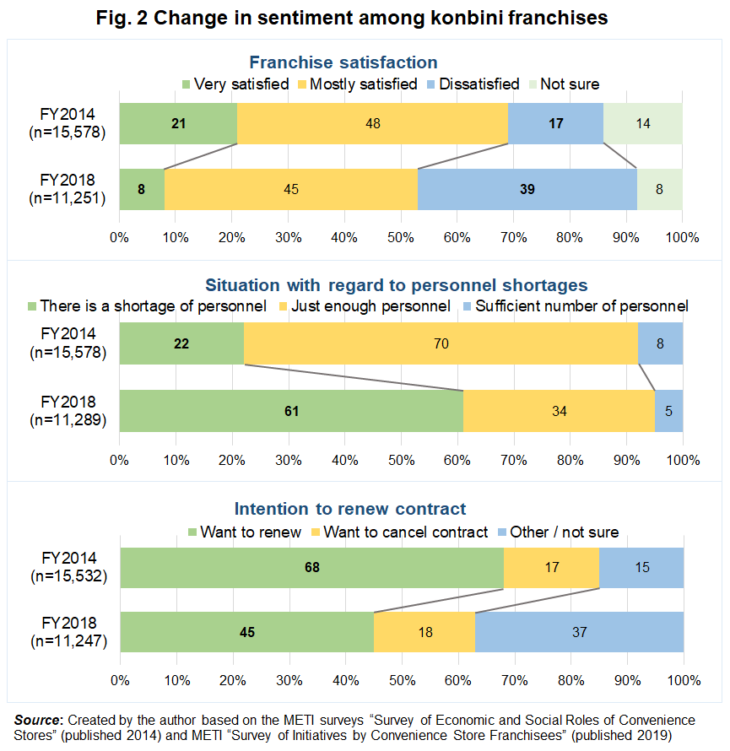

The third reason is more serious. Figure 2 shows a comparison between the results of a FY2018 questionnaire of konbini franchises conducted by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) between December 2018 and January 2019 with the results of a similar survey conducted in FY2014. For example, looking at “Level of franchise satisfaction” we can see that the number of franchises giving the response “very satisfied” has decreased, while the number of franchises answering “dissatisfied” has greatly increased. For “Intent to renew contract,” in the FY2014 survey around 70% of respondents answered “want to renew.” In the FY2018 survey, the number of respondents giving this response has fallen to less than half.

Until now, konbini stores have been maintained by franchises. If franchise owners become disaffected with the system, then the number of stores will begin to decline, and the effects will not be limited to just a decrease in existing stores. In the future, this will bring about a serious crisis that threatens the very survival of konbini. The reason for this is that, with such a large number of dissatisfied franchise owners, it seems unlikely that anybody will want to actively create new franchise stores. If the number of franchises decreases, then the financial power of the chain headquarters themselves will be depleted. Most critically, the number of nearby stores available to consumers will decrease.

The reason why the number of dissatisfied franchises has increased is that revenues have decreased, but the cause of this lies in the problem of personnel shortages and rocketing personnel costs. As shown in Figure 2, in the FY2018 survey, more than half of all stores answered that “there is a shortage of personnel.” It appears that over the past few years, stores which answered “just enough personnel” in FY2014 have now fallen into a state where they do not have enough personnel. However, in actual fact, franchises had already been complaining about personnel shortages at the time of a previous survey conducted in 2009.

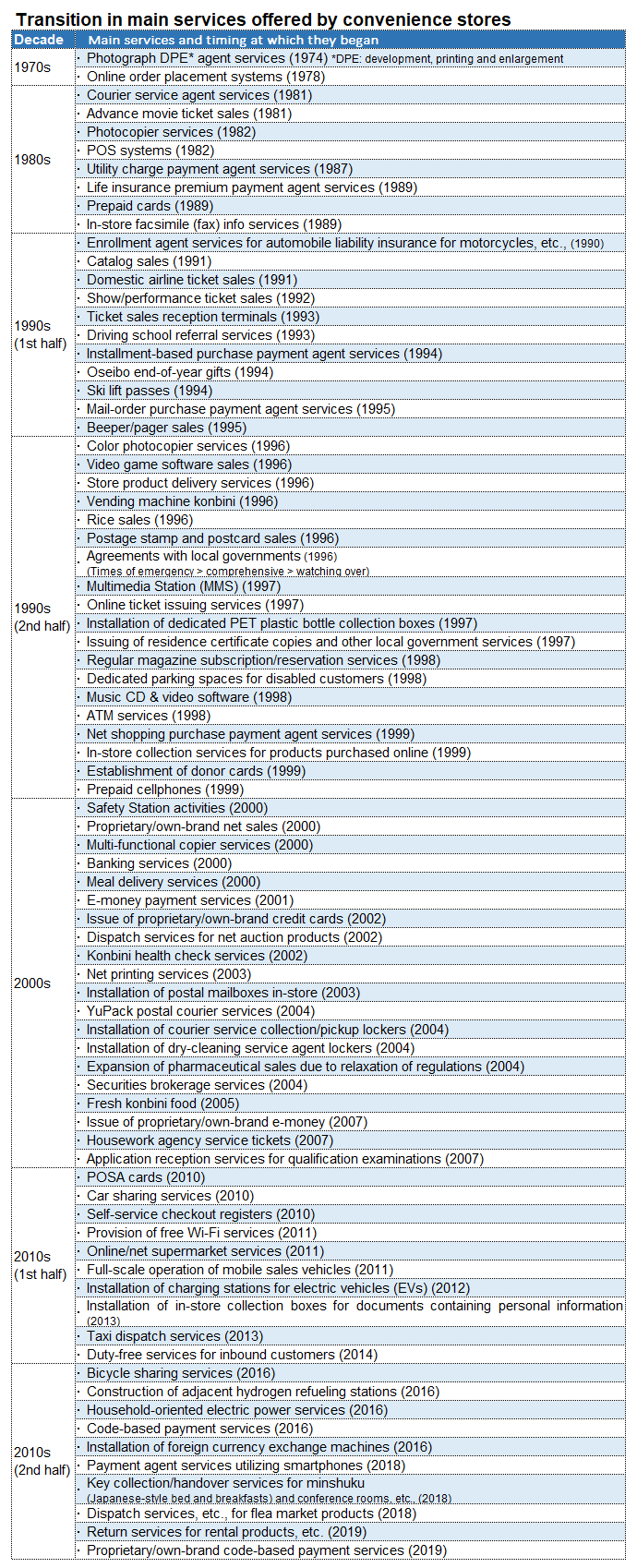

The number of services offered by konbini stores has continued to increase (refer to the table), and chain headquarters have also begun to encourage franchises to visit and take orders from customers (which also includes looking out for senior citizens), deliver products and offer mobile sales. It seems likely that we will see more franchises screaming out their dissatisfaction because they are unable to cater to these recommendations.

Of course, the chain operators have not just been sitting by idly and twiddling their thumbs. They have introduced self-service checkout registers, seeking to improve the efficiency of their operations and save on labor, and are also conducting tests with unmanned stores. They have dispatched temp staff to stores struggling with personnel shortages, and produced manuals for the acceptance of foreign workers. But despite these efforts, the problem of personnel shortages is not being alleviated. In fact, it is growing increasingly serious.

Figure 3 shows a comparison of results for the FY2014 and FY2018 surveys with regard to initiatives that franchise owners want to strengthen and/or implement. Looking only at Table 2, it seems that the decline in enthusiasm amongst franchise stores is unavoidable. However, the numbers of respondents answering that they would like to work at the two items “Recycle products that have passed their sell-by date” and “Increase/sell products using local produce” have increased from FY2014 to FY2018.

The former (i.e. recycling products that have passed their sell-by date) is an initiative to reduce food loss, which is becoming an increasingly serious social problem. It is actually the issue that hits closest to home for franchise store owners, and also generates a high level of interest and concern amongst local customers. Naturally, the latter (increase/sell products using local produce) also draws a great deal of interest from customers in local communities. Franchisees’ indicating their enthusiasm to engage in these initiatives tell us that, although it is difficult for them to pursue initiatives that require more manpower, they have not lost the desire to deepen the level of their relationships with their local communities. Until now, konbini as a part of social infrastructure have been supported by this kind of enthusiasm on the part of franchise store owners.

The road to transforming konbini into true social infrastructure

So, when did konbini begin to be a part of social infrastructure? Konbini first appeared in Japan around 1970, while the term “konbini” itself gained recognition amongst the general public by around 1990. Until that time, the stores had been referred to as shinya suupa (“late night supermarkets”) or mini suupa (“mini supermarkets”) with long business hours. They began to gain recognition as being different from existing retail business categories due to factors such as their development of product lineups that included ready-to-eat food products such as bento lunch boxes and onigiri rice balls, and their provision of various services, such as utility bill payment agent services.

As indicated in the table, konbini began to offer utility bill payment agent services in 1987. Seven-Eleven was the first chain to introduce the service, followed by similar services at Lawson in 1989 and FamilyMart in 1990. Such services were not limited to a single chain, and spread naturally to the other chains, helping to boost recognition for konbini as a distinct business category.

One key background point that made it possible for konbini to offer payment agent services for utility charges and other payments was that each of the konbini chains worked from an early stage to establish information systems utilizing Point of Sale (POS) systems. These information systems dramatically expanded the range of services that konbini could offer.

Between the latter half of the 1990s and first half of the 2000s, the number of services offered by konbini increased rapidly. This was the same time as the Internet gained widespread popularity and use amongst members of the general public, and net-related services also emerged. The number of tangible servicetype products also increased. These included postage stamps and postcards, video game software, and music CD & video software. The reason for this development was that konbini were approached by an increasing number of alliance partners wishing to utilize their store networks as platforms for approaching large numbers of consumers. To put it another way, konbini stores began to gain recognition as a form of media outlet. Although today the idea that “stores = media” is a typically accepted concept in the retail industry, at the time it was a progressive and pioneering concept.

The range of alliance partners wishing to utilize konbini store networks as platforms was not limited to other enterprises. Local governments, police and national government agencies also began to join in, and the paradigm of “konbini as a part of social infrastructure” was established.

Partnerships with local government began with the signing of agreements for during times of disaster, based on lessons learned from the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. The fact that konbini chains were able to provide various forms of aid and support in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake was also due to the accumulation of past efforts.

In “Safety Station activities” carried out by all of the konbini operators that are members of Japan Franchise Association (JFA), which began in 2000, konbini operators work in cooperation with police and fire department personnel.

During the mid-2000s, konbini began to form a string of comprehensive agreements with local governments for the purposes of offering not only emergency aid during times of disaster, but also the development of products making use of local produce, and the revitalization of local communities.

Moving into the 2010s, the number of agreements to watch for senior citizens and children increased, and konbini began to bolster their range of services, with delivery and mobile sales for people with difficulties in shopping instore, and housework and meal delivery services aimed at senior citizen households. Partnerships with local governments spread from the prefectural level to the local municipality (city, town and village) level, and the number of municipalities delegating local government services to konbini increased. In this way, konbini stores become more intimately linked with local communities. The increase in services relating to the sharing economy during the 2010s was also surely a reflection of the changing times.

Towards becoming a true part of social infrastructure

Amongst the many services offered by konbini, the services with the highest usage rates amongst customers are utility payment agent and automated teller machine (ATM) services. The former became recognized as a konbini service at the end of the 1980s, while the later gained recognition towards the end of the 1990s. There are many customers who visit stores with the specific aim of using these services, and use of these services has continued to increase at konbini as a whole since their initial introduction. They can be called the two major konbini services.

But what about in the future? For example, as Japan becomes a cashless society and the need to withdraw cash is reduced, consumers will most likely cease to appreciate the convenience that being able to withdraw cash at konbini ATMs 24 hours a day. The same applies for utility bill and tax payment agent services. Although konbini payment services were convenient for customers who did not use bank account transfer (direct debit) or credit card payments, if it becomes possible to pay easily using a smartphone—without going out of one’s way to visit a konbini—then the number of people who feel that the smartphone option is more convenient will surely increase.

There are also no other services (amongst those introduced at konbini since that time) which have grown to the level where they are used by customers to a greater extent than these two major services. Several services that require additional personnel—such as courier and meal delivery services—are also somewhat behind.

That being said, in order to survive in the current society with its shrinking and aging population, it is important to grow closer to local communities and develop stores that are trusted and depended upon by local people, rather Discuss Japan—Japan Foreign Policy Forum No. 55 than aiming to increase sales turnover as retailers. On the other hand, for consumers who currently use konbini, for as long as it remains impossible to handle everything using the internet, there will surely be a need for actual physical stores to remain.

For example, major konbini chains that have formed partnerships with the Urban Renaissance Agency (UR) are changing their product lineups and services on specific estates to match the need of residents living on those estates. Even without representative services such as the two aforementioned major services, all konbini really need to offer are services that are needed by local estate residents. Details of what those services actually are can be determined by discussion with the residents themselves.

The same applies for business hours. Necessary opening hours differ between areas and communities. There are already several konbini, such as those located in office locations in urban centers, which are not open 24 hours a day. Making people fit in with the system is a case of mistaken priorities. Systems must always change to match the behavior and needs of people.

In the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake, there were some konbini stores that operated when people from the affected areas assembled there. Stores provided chairs and tables, and became places where people from those communities could come together to eat and drink. Although there is a tendency for konbini—which began as a form of support for people living alone—to be viewed as having supported the culture of eating alone, they can also promote eating together. It can be said that with konbini, like many other things, it all depends on how they are used.

Going forward, too, it would be desirable to have stores that are operated by chonaikai (neighborhood association) members and other local volunteers. In order to enable this, it will probably be necessary to change the mechanism by which stores are established, and to take a flexible approach in reviewing and revising franchise membership conditions and how stores are actually operated. It is precisely this kind of response to change that makes konbini what they are.

References: Kato Naomi (2012) Konbini to nihonjin – naze kono kuni no bunka to natta no ka (Konbini and the Japanese People – Why Konbini Became Part of Japanese Culture), Shodensha Publishing

Translated from “Tokushu 1 ― Konbini wa Shakai infura ka: Konbini ga shin no shakai infura de arutameni (Special Feature—Are Konbini a Form of Social Infrastructure? What is Needed for Konbini to Truly Become a Part of Social Infrastructure),” THE TOSHI MONDAI (Municipal Problems), October 2019, pp. 4–10. (Courtesy of The Tokyo Institute for Municipal Research) [December 2019]

Keywords

- Kato Naomi

- consumer affairs

- konbini

- convenience stores

- oligopoly

- e-commerce

- labor shortage

- Urban Renaissance Agency

- social infrastructure

- ATMs

- cashless society

- local communities