Tokyo sunk: The day when Weathering with You becomes a reality

The Arakawa River overflows its banks, leaving 2.5 million people submerged in water: The residents of the five Koto, or east-of-the-river, cities have no other choice but to evacuate.

Tsuchiya Nobuyuki

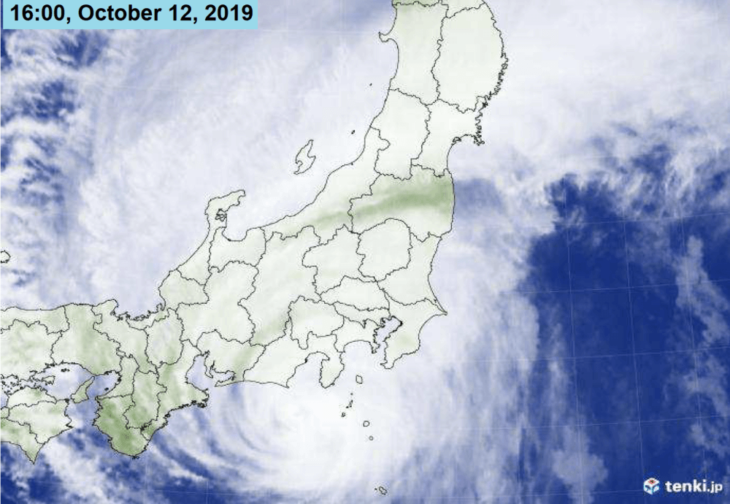

Typhoon Hagibis made landfall on Japan’s mainland on October 12, 2019, causing enormous damage for two days. The typhoon left 88 people dead and seven missing nationwide (as of October 26), and a total of 281 rivers overflowed their dikes.

More than other events, the overflow of the Tama River shocked many people, who then realized that even the center of Tokyo cannot ignore the danger of floods. The water level of the Tama River began to rise after 6:00 AM on October 12 and overflowed at 10:00 PM. The water level reached waist-deep in a residential area of the Denen-chofu district of Tokyo’s Ota City. From its southwest side, water infiltrated Futako-Tamagawa Station in Setagaya City, where the dikes had been underdeveloped, and the City was inundated with water.

| Typhoon Hagibis made landfall on Japan’s mainland on October 12, 2019 |

Source: Kanto Regional Development Bureau, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport |

Typhoon Hagibis also caused serious damage to other urban districts of Tokyo, but the damage could have been far worse. A close examination of the rivers and dams shows that the potential for crisis had indeed been there. If things had taken a slightly different turn, the submerged Tokyo depicted in the Japanese animated film Weathering With You, directed by Shinkai Makoto, might have become a reality.

Many rivers, such as the Arakawa, Edo, and Sumida rivers, run through five cities in the Koto area of southeast Tokyo, Sumida, Koto, Adachi, Katsushika, and Edogawa Cities, that are often called Shitamachi. The rivers are sourced in mountainous areas of the Kanto region and the rain that falls onto the region ultimately runs down through this area. That is why flood control measures must be implemented, including dams, retarding basins and discharge channels.

During Typhoon Hagibis, the facilities in the upper, middle and lower reaches of the rivers were able to prevent the movie’s submerged Tokyo from becoming a full-scale reality.

Within 50 centimeters of the dangerous water level

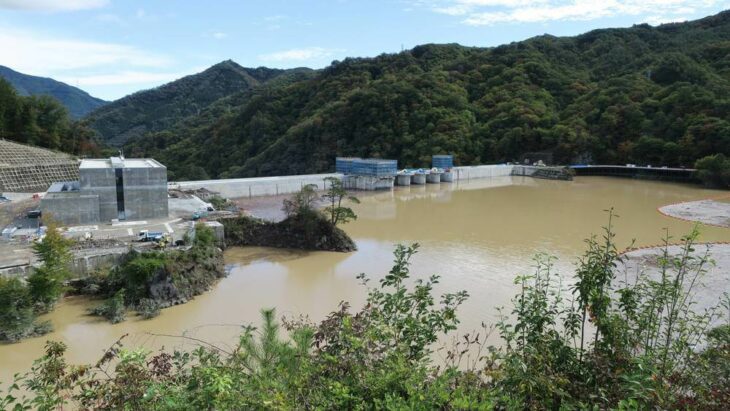

Yanba Dam photographed on 20 October 2019.

Source: Qurren (talk) / Creative Common

Yamba Dam in Gunma Prefecture, a part of the Tonegawa River system, which had just started water storage tests, started controlling floodwaters immediately. Due to the heavy rainfall, the water level of Yamba Dam rose about 54 meters between dawn on October 11 and the morning of October 13, collecting 75 million tons of water, well above its assumed upper limit of 10 million tons, and completely over its full capacity. When the former Democratic Party of Japan was in power, it had questioned the effectiveness of Yamba Dam and suspended the construction of the dam. But if it had not been for this dam, the situation faced by the Tonegawa River system would have been much more tense.

Retarding basins, such as the Watarase retarding basin in Gunma Prefecture, and the Sugo retarding basin in Chiba Prefecture, collected an approximate total of 250 million tons of water, preventing flooding.

The Iwabuchi Watergate in Kita City was pressed into service as a discharge channel. This floodgate that divides the Arakawa and Sumida Rivers was closed on the evening of October 12 to prevent water from the swollen Arakawa River entering the Sumida River.

The Iwabuchi Watergate is one of the possible points where the Arakawa river may overflow its banks. On the morning of October 13 the water level went well above Level 2 of a five-level system with the danger levels of Overflow caution water level (Level 2), Evacuation water level (Level 3), Dangerous water level (Level 4), and Overflow (Level 5), and was getting within 50 cm of Level 4.

|

|

|

Old Iwabuchi Watergate (left) was built in 1924 and the new watergate in 1982 |

|

The Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel in Kasukabe City in Saitama Prefecture, known as the Underground Palace, also worked effectively. This discharge channel plays a role in protecting Edogawa City and eastern Saitama from flood damage by discharging water to the wider Edogawa River to prevent five small and mid-sized rivers in the upper reaches from overflowing.

The Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel in Kasukabe City in Saitama Prefecture

The discharge channel operated for the first time in four years, discharging about 11.51 million tons of water between October 12 and the afternoon of October 15. It was the third largest discharge since the facility was completed in 2006. But if the discharges cause the Edogawa River to overflow, the consequences would be horrendous. That is why workers had to make difficult decisions while measuring the water levels of each controlled area around-the-clock, adjusting the amount of water to be discharged. Just a small mistake could lead to a major accident. The workers had to work under these very tense conditions.

As noted above, many flood control facilities operated almost to their limits, which made it possible to avoid a worst-case scenario in which Tokyo was submerged by Typhoon Hagibis. But no one knows what would have happened if it had rained a little more heavily or if Typhoon Hagibis had traveled a little more slowly.

In fact, an evacuation advisory was issued for 432,000 residents of Edogawa City on the morning of October 12 as Typhoon Hagibis raged. The potential crisis of the flood of Arakawa River was drawing that near.

Shitamachi: literally low

As a public works manager of the Edogawa City Office, I have engaged in sewage and river projects as a for many years. This experience has shown me that Weathering With You is not just a flight of fancy.

There is concern that the five cities in the Koto area of southeast Tokyo in particular could be seriously damaged by floods. A particularly terrible scenario would be the simultaneous flooding of the Arakawa and Edogawa Rivers in conjunction with tsunami.

Showing the areas commonly known as Yamanote and Shitamachi, the figure illustrates that the lands of the Shitamachi area, which translates literally to “low town,” are literally low-lying, just to the east of the Yamanote Line. In addition to the lands being low, many small factories were built in the area during the rapid economic growth period, leading to the water and gases underground to be pumped up, which in turn led to further land subsidence and the creation of an area below sea level, or a “zero-meter area,” that is lower than the sea level at low tide.

Tokyo was originally land formed by the soft earth and sand cut from mountainous areas sedimenting after the rains that fell on the entire Kanto region ran into its rivers, including the Arakawa River, resulting in these low lands slightly above sea level. The earth and sand were carried by what is now the Sumida and the Edogawa rivers. The current Sumida River was called the Arakawa River during the Edo period (1603–1867). Connected to this, the current Arakawa River refers to the Arakawa basin, which was originally dug to prevent the Sumida River from rising.

Source: Created by Discuss Japan based on data from the Katsushika City http://www.city.katsushika.lg.jp/_res/projects/default_project/_page_/001/018/693/hmbig3-4.pdf

Before the Edo period, all of the large rivers in the Kanto region, such as the Tone, the Watarase and the Arakawa rivers, emptied into Edo Bay.

The paths of these rivers were changed significantly in the Edo period (1603-1868) with the eastward relocation of the Tone River and the westward relocation of the Arakawa River by Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), a major relocation project involving the Tone and the Arakawa rivers. The key to developing the Kanto Plain was flood control and irrigation.

In order to protect the eastern part of the Saitama Plain from floods, promote new rice paddy development, protect old rice paddy areas like the Kumagaya-Gyoda area and prevent floods in Edo at the same time, Ieyasu separated the Arakawa River from the Tone River, dug a new river and changed the river routes to their modern paths, where they empty into Edo Bay (currently Tokyo Bay) via the Sumida River.

But with the increase of the population amid the urbanization of the Meiji period (1868–1912), flood damage become a more serious concern. This is because even though the river routes had been changed by force, in the event of a flood, the rivers would revert to their previous paths.

The Arakawa basin disappeared

In the Great Kanto Flood of 1910 the entire Kanto Plain was inundated. This massive flood caused enormous damage, leaving 1,357 people dead or missing nationwide, with roughly 6,600 houses completely destroyed or washed away, and 518,000 houses flooded to just under or even above floor level, and the collapse of dikes occurring at 7,063 locations. For the Meiji Government, the severe flood damage drove home the importance of flood control measures to protect Tokyo, the capital of Japan.

As a part of the drastic measures to protect Shitamachi, Tokyo, from flooding, the Meiji Government embarked on the project of cutting and opening the Arakawa basin. This included the mind-bogglingly grand construction project of building a floodgate in the Iwabuchi district of Kita City, dividing the main branch of the Arakawa River (currently the Sumida River) and digging a 500 m-wide canal extending 22 kilometers from Iwabuchi to the mouth of the then-Nakagawa River. The project was intended to build a mechanism in which the Iwabuchi Watergate could be closed in the event of a flood to control the rise of the main branch of the Arakawa River and enable most of the water to run straight into the sea through the wide Arakawa basin.

The entire construction project was completed in 1930 after 20 years of construction. The Arakawa basin was later renamed the Arakawa River in 1965 and the entire old Arakawa River branching from the Iwabuchi Watergate came to be called the Sumida River as a part of this.

That is, the word Arakawa basin has now vanished from the map. The memory of the long history of floods and flood control measures have also faded away. In the current situation, I am concerned that people have forgotten their fear of flood damage.

Midnight evacuation drill

Even with the existence of the Arakawa basin, Japan experienced major flood damage after World War II. One of those disasters was Typhoon Kathleen in 1947, which left 1,930 people dead or missing.

At the time, the Arakawa basin went more than 1 m over its assumed highest water level at Iwabuchi. Although no dams burst along the Arakawa basin, the upper reaches of the Arakawa River overflowed its banks. In addition, the upper reaches of the Tone River overflowed in Kurihashi Town (currently Kuki City), Saitama Prefecture, which caused the area between the Tone River and the Arakawa basin to flood, resulting in the water staying there for many days. Because some places were lower than sea level, once they were submerged, the water stayed for a long time.

The house where I was born and raised was located near the site where the river overflowed in Kurihashi in 1947. But because it was a place built up by the earth and sand that were dredged during the Tone River improvement project, it was in a place higher than its surroundings by four to five meters; it did not become submerged, and was free from damage. The house where I was born and raised became an evacuation site for many people.

About those events, my mother remembers that when day broke, she saw that all the houses at the low point were buried in a sea of mud, except for their roofs. The sound of muddy water running was really terrible and the area was filled with an unbearable odor. The odor was a mixture of the mud from collapsed rivers, field cesspits and the excrement from the toilets of each home.

It was such an intense experience to her that she sometimes woke me up suddenly in the middle of the night for an emergency drill after I was old enough to understand.

When she woke me up, my mother told me to change clothes and run away from the front door. After getting dressed in complete darkness, I was told to feel for the door, open it and go in the direction of the front door along the walls of the corridor. As the drill was a complete surprise with no prior notice, it proved to work well.

When I went to the Mizue district in Edogawa City as an official of the Edogawa City Office to ask for the zoning of lands to be readjusted, the owner of a house took me to a pillar with a large square hole in it at about my height from the floor.

The man said to me, “Do you know what this hole is for? If you do, I will agree to the land adjustment.” But I had no idea.

After I investigated and asked other people for help, I was unable to find the answer. I gave up, visited the house again and asked the man for the answer. He explained that when a flood came, people would insert crossbeams into the hole, or mortise, in the pillar, spread sheathing roof boards, raise the tatami mats onto them and use it as a raised floor. It is just like making a mezzanine floor in the house. This made me realize how usual and familiar it was for houses to be inundated in that area.

Some 310,000 people have nowhere to go

I have been involved in flood control projects for many years. We are protected by many flood control facilities built by previous generations. But, disappointingly, even such measures cannot 100% prevent flood damage. We should be mentally prepared for the reality that floods can happen at any time, and we must protect ourselves.

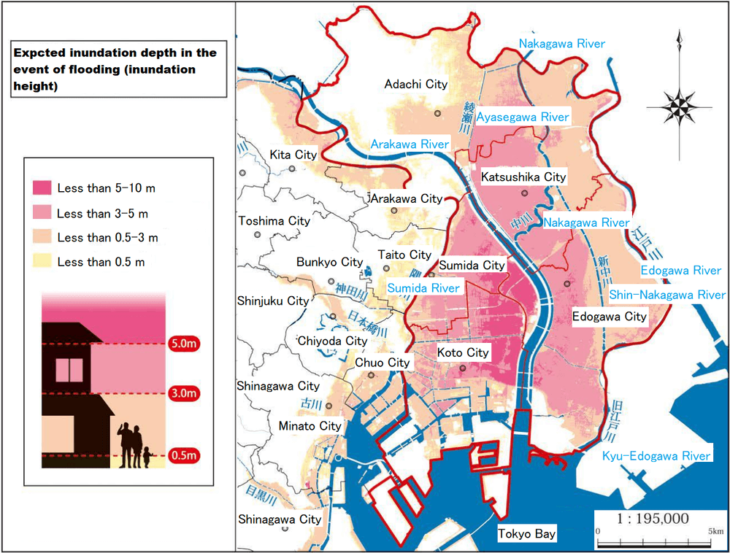

Now, the hazard map that was drawn up with this in mind is gradually becoming a topic of discussion. In 2008 I was also involved in the drawing up of a flood hazard map compiled by the Edogawa City Office.

Edogawa City is a zero-meter area about 70% of which is below sea level. The highest area is near Koiwa Station, about 1.6 meters above sea level. The Edogawa City Office is about 1.7 meters below sea level. With an elevation change of just 3 meters, the land is almost flat and there is no high ground for people to evacuate to in the event of flood.

In addition, Edogawa City is vulnerable for the following reasons.

- There are five large rivers that can bring floodwaters into the area, including the Edogawa, Arakawa, and Nakagawa rivers.

- Because the area is largely divided into three sections by these rivers, the sections may be isolated in the event of a flood.

- Most of the houses in the area are two-storied wooden buildings, with only a few three-storied or taller reinforced concrete buildings within the area that people can evacuate to.

More terribly, the private buildings that people can evacuate to only have the capacity for 150,000 people, and if you include the elementary and junior high schools, the unsubmerged floor area will only be enough for 370,000 people. The population of Edogawa City is about 680,000. It is said that evacuation is important in a disaster. But where should 310,000 people with nowhere to go evacuate?

In response to this, we have reached the conclusion that we should turn to Ichikawa City, Chiba Prefecture, outside Edogawa City to identify evacuation areas in the face of this overwhelming shortage.

This followed the example of the previous floods that Edogawa City had experienced. When Typhoon Kathleen hit the area in 1947, people with nowhere to go crossed the flooded river and fled to Konodai, in western Ichikawa City. The number of evacuees reached 10,000, or about 10% of the population of Edogawa City at that time.

Of course, Edogawa City cannot unilaterally evacuate its residents beyond its administrative areas. Edogawa City negotiated with Ichikawa City and concluded an agreement for the evacuation of about 200,000 people in advance of a flood to a temporary evacuation site.

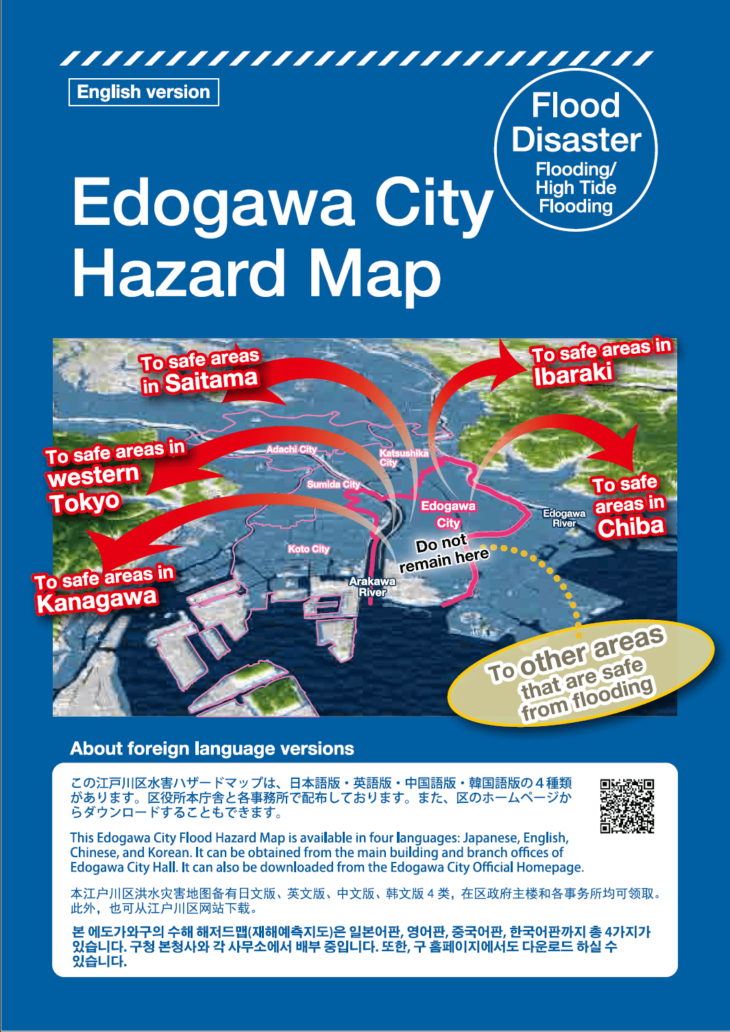

| Edogawa City Hazard Map |

Source: Edogawa City Office, |

This year the Edogawa City Office revised the Edogawa City Hazard Map for the first time in 11 years and distributed it to all households in the City. This map illustrates in an easy-to-understand way with colorful aerial photos a hypothetical flood of the Arakawa River and the Edogawa River that would cause almost all of the City to be submerged.

In addition, on the cover of the map was a bold-letter statement, “Do not remain here,” on top of the location of Edogawa City. Tens of thousands of people cannot evacuate all together in a short time. When people leave the City area, they have to cross a bridge; it is clear that major confusion and traffic congestion will occur. Considering this, we felt the need for straight talk communicating the need for residents to evacuate to areas outside the City as quickly as possible in an emergency.

The regional evacuation plan for major floods and hazard map for a major flood in the five cities of southeast Tokyo can be said to be a developed version of the Edogawa City hazard map. In August 2018, the five cities set up a council and released a regional evacuation plan to assist all area residents to evacuate to areas outside the Cities. This is because the five adjacent Cities drawing up separate, uncoordinated evacuation plans would make no sense.

The five Cities’ regional evacuation plan

Arakawa River, Adachi City

Although the five cities in the Koto area have a population of about 2.62 million people, most of the land is within the zero-meter areas below the high-tide level with no elevated places to evacuate to within them. People cannot evacuate to high buildings in a situation in which lifelines are cut for a long time. They have no other choice but to evacuate to places outside the area to survive.

The council’s hypothetical damage area covers almost the entirety of the five cities, projecting the flooding of more than 90% of the area. Shockingly, about 2.5 million people (the estimated nighttime population), more than 95% of the total population of the five Cities, live in the flooded area.

The floodwaters are assumed to be up to 10 meters deep around the north gate of JR Sobu Line Hirai Station. In addition, it has been projected that the floodwater will remain in some areas for more than two weeks.

Ultimately, residents of the five cities are left with the option of advancing a wider ranging evacuation within a safe time period. Considering this, the council of the five cities drew up the following four-step regional evacuation plan.

1 Three days before (72 hours ahead) ―― “The first thing you should do is to prepare for evacuation!”

If a forecast 72 hours prior to a typhoon shows that the typhoon’s forecast circle with a central atmospheric pressure less than 930 hPa will cover the Tokyo area, collaborations between the section chiefs of the crisis management departments in the five cities in the Koto area will begin, reacting according to information provided by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and river management officials.

2 Two days before (48 hours ahead) ―― “Please evacuate to a safe place outside the area!”

Residents are called on to always consider wider-range evacuation sites by themselves, gather information, make decisions on their own and voluntarily evacuate to these wider areas once voluntary wider-range evacuation information is sent. Residents should evacuate to the houses of relatives and friends or other accommodation facilities they have identified themselves as quickly as possible. They are urged to choose by themselves the appropriate means of transportation, such as on foot, by train or by bicycle, because public evacuation methods cannot be secured.

3 One day before (24 hours ahead) ―― “You cannot stay in the area!”

With attention paid to the projected times of the arrival of the windspeed zones specified in the windstorm warnings (projected times when winds will reach certain speeds), a wider-range evacuation advisory is issued before it becomes impossible for people to evacuate due to the wind. The focus is on residents living within the areas that are projected to flood above floor level.

4 Nine hours before “Call for the vertical evacuation of residents in areas forecast to flood (urgent)” ―― “Please stop evacuating to wider areas and evacuate to rooms in your home higher than the floodwaters or the nearest tall facility!”

Residents stop evacuating to a wider-range area and vertically evacuate to the rooms of their homes higher than the floodwaters or the nearest tall facility.

I strongly hope that a situation of this kind will never happen. But it is not just a fantasy and can happen at any time. If things had been just a little different during Typhoon Hagibis, such a situation might have happened. To express this, I published Shuto suibotsu and Suigai retto (Bunshun Shinsho). I sincerely hope that as many people as possible will come to understand this crisis.

Translated from “Tokyo Chinbotsu ‘Tenki no ko’ ga genjitsu ni naru hi—Arakawa kekkaide 250 mannin ga mizubitashi ni naru: Koto 5 ku no jumin wa ikigaini hinansurushikanai (Tokyo sunk: The day when Weathering with You becomes a reality—The Arakawa River overflows its banks, leaving 2.5 million people submerged in water: The residents of the five Koto, or east-of-the-river, Cities have no other choice but to evacuate),” Bungeishunju, December 2019, pp. 124–131. (Courtesy of Bungeishunju, Ltd.) [March 2020]

Keywords

- Tsuchiya Nobuyuki

- Japan Riverfront Research Center

- Bungeishunju

- Weathering with You

- Arakawa River

- Typhoon Hagibis

- Typhoon 19

- Tokyo flood

- Arakawa river

- Arakawa basin

- Koto wards

- Edogawa Ward

- hazard map

- evacuation