The Trends Created by the Self-Cultivation Boom: Self-Improvement in Modern Japan

|

|

|

|

| “The self-cultivation boom in modern Japan was richly varied, ranging from cold-water bathing to meditation, reading, even savings. […] Even though the approaches have changed with the times, self-cultivation emerges out of similar soil and seeds to blossom differently in each age.” | |

Osawa Ayako, Religious scholar, Research fellow, Japan Society for the Promotion of

Science

The Roots of Self-Development

Osawa Ayako, Religious scholar

From day to day, quite a few people harbor the feeling that they want to grow and become a wonderful person. Some people make stoic efforts to turn themselves into the person they want to be, practicing Zen meditation or other behaviors advocated by people they idealize. The thoughts and actions that encourage us to improve ourselves are called self-development. How have these practices and this kind of thinking taken root in Japanese society?

The clue is in the idea of shuyo (hereinafter, self-cultivation). Self-cultivation is to actively nurture one’s own character and personality and to improve one’s mind. In Japan, the concept of self-cultivation, which is at the root of self-development, emerged in the Meiji period (1868–1912). This is when the term self-cultivation, rarely heard in early modern times, came into widespread use as a term that stood for striving to become the person you should be. Ever since, how to develop oneself as a person has been a major theme that is never far from the minds of Japanese people. It has also been associated with religion in no small measure.

Matsushita Konosuke and Self-Cultivation

Let us take the example of Matsushita Konosuke (1894–1989). Starting out as an apprentice and going on to build one of Japan’s largest companies, Matsushita advocated the principle of self-help efforts that are rooted in working life to his employees and society at large. After the war, he established the PHP Institute to promote his ideas more widely in society. He also expanded his activities by organizing lectures, workshops, and publishing monthly magazines. PHP stands for Peace and Happiness through Prosperity. Many managers try to apply his philosophy of recognizing one’s own mission to company management, and many working adults also turn to him for inspiration. Matsushita was affiliated with many religions, and the Kyoto headquarters of the PHP Institute even has its own shrine (Kongen no Yashiro). He was known as the god of management, and some readers may find his life and his ideas religious. But he was neither a religious person, nor did he study any particular religion in depth.

On the other hand, Suzuki Seiichi (1911–80), the founder of Duskin Corp., based his management policies on religious beliefs. He studied with Nishida Tenko (1872–1968), who founded Ittoen, a non-denominational self-cultivation body, and advocated Prayerful Management in the hope of unifying business and morals. The Heart Sutra is recited every morning in the workplace, and employee training is conducted at Ittoen. In addition to zazen and meditation, the trainees visit homes in the neighborhood and clean toilets free of charge during their training. It is a kind of practice where you gladly perform the tasks people dislike the most, own nothing of your own, and dedicate yourself to cleaning out of gratitude for being useful. Ittoen carries out these practices in the manner of a religion, but it is not a religious corporation, neither was Nishida a monk or a new religious leader. Duskin employees who undergo training at Ittoen are not required to convert to any faith. Suzuki’s philosophy, which inclines toward Nishida, tends to be shared by the employees and this has become the pillar of the company.

These are some examples of entrepreneurs with charismatic mentors who counseled their employees on the importance of spiritual growth and self-reformation and linked their ideas to working styles and company management. Self-cultivation is a good fit with religion, and there are many cases of incorporating religious elements such as Zen meditation, meditation, or sutra chanting. Self-cultivation has been absorbed into daily life while maintaining a certain distance from temples, churches, and other religious organizations or religions. It is not only connected to the spiritual improvement of individuals, but also to life lessons, family life guidelines, the workplace and social ideals.

The First Self-Development Book in Modern Japan

There are two types of self-cultivation: the one that aims for one’s own spiritual improvement and the other one that aims for social success by these means.

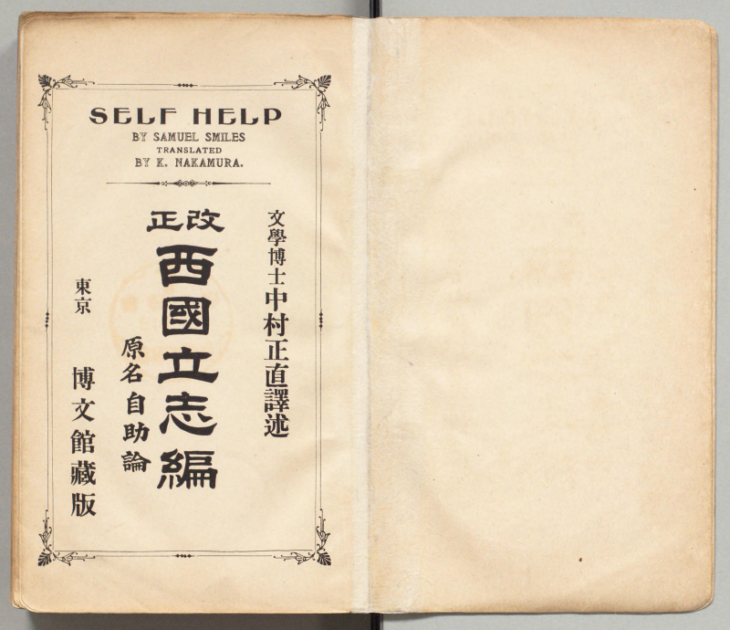

The first book to use self-cultivation in the sense of actively seeking spiritual growth was Saigoku risshi hen—Genmei jijoron (hereinafter, Saigoku risshi hen) translated by Nakamura Masanao and published in 1871. A translation of Self-Help by the English author Samuel Smiles (1812–1904), the book was a bestseller typical of modern Japan.

Title page of Saigoku risshi hen—Genmei jijoron, revised edition, 1916. Nakamura Masanao’s translation of Self-Help by Samuel Smiles was first published in 1871.

Courtesy of National Diet Library Digital Collections

I believe that this book was the first self-development book in modern Japan. These days there are many types of self-development, but the essence is to aim for personal growth, which is basically the same idea as the self-cultivation advocated in this book. The attitude of being aware of reforming one’s own consciousness, which is required for self-development, is exactly the same as in this book. As mentioned below, those who were influenced by Saigoku risshi hen made their names as writers of self-development books.

The overwhelming majority of self-development books are business-related and authored by men. Seeing that the books were written by men who enjoyed social status, the self-development book is a male-centered medium (Makino Tomokazu, Jikokeihatsu no jidai ([The Age of Self-Improvement]). Saigoku risshi hen is also inseparable from the male perspective. An introduction to the self-help efforts of about 300 historical figures—all men—including Francis Xavier, Isaac Newton, and James Watt, the book advocates the ideals of risshin-shusse (personal advancement). The book is very easy to understand and describes in detail how to behave and how to work hard to succeed.

Most people drawn to this book were men. In addition to Shibusawa Eiichi (1840–1931) and others, this book also inspired the typical Meiji entrepreneur including Okura Kihachiro (1837–1928), who set up several companies including the Rokumei-kan,[1] the Imperial Hotel, and Okura Gumi Shokai (currently, Taisei Corporation). Saigoku risshi hen became a so-called bible that provided Meiji youths with spiritual support, something that is described in the short story Hibonnaru bonjin [An extraordinarily ordinary man] by Kunikida Doppo (novelist, 1871–1908). Hoshi Hajime (1873–1951), founder of Hoshi Pharmaceutical Co. and father of the science-fiction writer Hoshi Shinichi (1926–97), loved the book to distraction. (Hoshi Shinichi Meiji no jinbutsushi [Representations of personalities from the Meiji period]). These were men who nursed thoughts of personal advancement.

The Self-Cultivation Boom and the New Era of Finding Oneself

In the third decade of the Meiji period (starting from 1897), self-cultivation as advocated in Saigoku risshi hen became linked to social success and personal advancement. In the preceding decade, Christians and Buddhists had started to discuss ideas of spiritual growth. This is where the elite of highly educated young people played an important role. Many of them read the Bible out of a keen interest in Christianity or practiced Zen meditation (Kurita Hidehiko, “Shuyo and a Conception of Future Religion at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” Journal of Religious Studies, 2015 Volume 89).

Taking on a religious tinge, self-cultivation became popular among the youths of the new era as a philosophy for improving one’s character or finding oneself.

The promulgation of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan, the Imperial Rescript on Education, and the Sino-Japanese War in the second decade of the Meiji period (from 1887) required self-awareness of the citizens of Japan. Therefore, self-cultivation was also employed as a form of self-education and training to turn oneself into a person fit for modern society. It became a philosophy for actively improving one’s mind and character, which gradually replaced the formal shushin (moral training) education (Wang Cheng, “The Emergence of the Concept of ‘Shuyo’ in Modern Japan,” Nihon Kenkyu, No. 29, International Research Center for Japanese Studies [Nichibunken]).

After the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) and into the fourth decade of the Meiji period (from 1907), books on self-cultivation appeared like bamboo shoots after the rain. The boom in self-cultivation had arrived. The context was the emergence of new types of youths including the hanmon seinen (anguished youth), who struggled in life for lack of food and money, the seiko seinen (youths seeking success), who aimed for social success regardless of academic background, and the daraku seinen (degenerate youth), who glorified physical love. The varied situations of these youths became the breeding ground for one self-cultivation group or publishing culture after another including the shuyodan (self-cultivation groups), seinendan (young men’s associations), and Kodansha (currently, a publishing company, Kodansha started out as Dai-Nippon Yubenkai, Greater Japan Oratorical Society in 1909) (Tsutsui Kiyotada, Nihon-gata “kyoyo” no unmei [Destiny of the Japanese style “kyoyo”]). While maintaining some degree of connection with traditional religion, the spiritualism of Kiyozawa Manshi (1863–1903), the Ittoen mentioned earlier, the Muga-en (Garden of selflessness) of Ito Shoshin (1876–1963), and the Seiza-ho (method of breathing and sitting quietly) of Okada Torajiro (1872–1920) and other new thought movements and groups of the period were not a good fit with traditional religion. One of the reasons for the religious tinge to modern self-development is the great social impact of these movements and groups and their messages of self-cultivation, which fall somewhere between traditional religion and non-religion.

As the Meiji period drew to a close, self-cultivation became even more popular throughout society because it was often featured in magazines for female students and the younger generation, literary magazines, or general magazines such as Chuokoron. As Oriental culture made a comeback around the time of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), people became more interested in Zen thought and The Analects, and started to reconsider the traditional ideas of human development (Tajima Hajime, Shonen to seinen no kindai Nihon [Modern Japan of boys and youth]). As physical self-cultivation, which advocates the union of mind and body, flourished, Zen training and the precepts of early modern Japan attracted attention. Self-cultivation was also incorporated into school education, a trend that became linked to collective education and training.

The facts of self-cultivation are very vague. There are no set rules of what self-cultivation is or what you can do to achieve self-cultivation. This is precisely why different people advocated and practiced different methods of self-discipline. (Wasaki Kotaro, Meiji no seinen [Youth in Meiji]).

The Success Boom and Financial Success

Some of the self-cultivation boom flowed into the beginnings of the success boom in the late Meiji period and the Taisho period (1912–26). Self-development books are often about success in business, but the Saigoku risshi hen, which advocated self-help efforts, was still widely read in the new era. In a society where capitalism was making inroads, self-cultivation was connected to the desire for personal advancement based on financial success.

Murakami Shunzo (1872–1924), the founder of Seiko Zasshisha publishing company, symbolizes this trend. After reading Saigoku risshi hen and becoming engrossed in Smiles, he launched the magazine Seiko (Success) in 1902. It was a magazine for youths who aspired to create their own destiny through their self-help efforts. Along with the business magazine Jitsugyo no Nihon, Seiko pioneered the success boom and became favorite reading for youths aiming for personal advancement. (Incidentally, Sosuke, the main protagonist in Natsume Soseki’s Mon (The Gate), picks up this magazine in the dentist’s waiting room.)

Youths who wanted to move up in society, but could not go to school for financial reasons, would read these magazines, buy transcripts of lectures for junior high school (under the old educational system; currently, senior high school), or entrust their dreams to correspondence courses designed to pass qualification examinations (Takeuchi Yo, Risshin shusse shugi [Careerism]—enlarged edition.)

Murakami was deeply committed to religious thinking including Zen and the Hotoku thought of Ninomiya Sontoku (1787–1856), but he gradually started leaning toward the Americanized principles of money-making. Sekai daifugo risshin-den (The story of the success of international millionaires) published by Seiko Zasshisha celebrates the enormous wealth acquired by a number of Anglo-American millionaires as evidence of success. The lineup of stories includes, for example, “The success story of Amasa L. Stanford, an exemplary businessman,” or “The success story of the British railway king, James J. Hill.” The magazine also ran features on “The poverty years of Meiji celebrities,” which included stories about Yasuda Zenjiro (1838–1921) who founded Yasuda Zaibatsu, the proprietor of the famous Eitaro confectionery, Ito Hirobumi (1841–1909), Iwakura Tomomi (1825–83) and others. The stories highlighted how they had struggled with poverty and hardship before gaining their wealth and status. The attitude of making the effort to help oneself without giving in to poverty became linked to social success. But that is not all: Murakami also set up Seiko Kurabu (Success Club) to break the island mentality of Japan. In addition to funding exploration expeditions, Murakami declared that he would develop human resources who could survive the competition with Western great powers. He also became an expansionist who supported the rule of other countries by force.

Seiko was soon discontinued and Murakami poured most of the proceeds from the magazine into the Antarctic exploration business. The first Japanese Antarctic expedition led by Shirase Nobu (1861–1946) was a success, but Murakami died in unhappy circumstances. The new era of self-discovery was the end result of being caught up in the rise of a competitive society.

Modern Japan and the Popularity of New Thought

Like Murakami, the American writer Orison Swett Marden (1850–1924) was influenced by Smiles and advocated positive thinking based on the New Thought philosophy. New Thought is an alternative spiritual movement in the United States, derived from Christianity toward the end of the 19th century. The emphasis on positive thinking, such as “thoughts become reality” and “if you think positive, your wishes will be fulfilled,” probably originated with New Thought (Barbara Ehrenreich [1941–], Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking Is Undermining America).

Seiko, the magazine published by Murakami, was modeled on the self-development magazine SUCCESS, founded by Marden and still published today. Marden was an ardent follower of Nakamura Tenpu (1876–1968) and even went to see Nakamura when the latter visited the United States. Nakamura was the founder of Tenpukai, which provides venues for mental and physical training and still enjoys the support of many people. Marden was enormously popular in Japan from the Meiji to the Taisho period. In Meiji Japan, the most widely read Western book was a translation of Pushing to the Front (1894), and his other books were also translated in quick succession (Earl H. Kinmonth, The Self-Made Man in Meiji Japanese Thought: From Samurai to Salary Man). Both Seiko Zasshisha, Murakami’s publishing house, and Jitsugyo no Nihon published many of Marden’s books.

Seiko Zasshisha also published Ambition and Success, and The Secret of Achievement (Sekai Seiko Bunko, first edition). The publisher even printed up some quotes from Marden such as “Self-cultivation in a time of progress” or “Self-confidence carries conviction.” In addition, Jitsugyo no Nihon printed booklets of success stories such as Qualifications for Success, Success Nuggets, as well as Cheerfulness as a Life Power, Prosperity, How to Attract It, and other books that linked positive thinking with success. Titles such as The Optimistic Life, Peace Power and Plenty, The Power of the Mind to Compel the Body, and How to Get What You Want, and other books by Marden were published by other companies from the late Meiji to the Taisho period.

Similarly, from the late Meiji period to early Showa period, several translations of Ralph Waldo Trine (1866–1958), who also subscribed to the New Thought philosophy, were published. The success and positive thoughts connected to self-development had a great impact on both Nakamura Tenpu and Taniguchi Masaharu (1893–1985), who started the new religious group Seicho-no-Ie. This is where we find the origin of modern self-development.

Jitsugyo no Nihon and Nitobe Inazo

Nitobe Inazo (1862–1933) was involved with Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha, Ltd., which published many of Marden’s books. He served as an editorial advisor to Jitsugyo no Nihon for three years from 1909 and wrote many articles for the magazine. His Shuyo (Self-cultivation) (1911) and Yowatari no michi (How to make your way in the world, 1912) were best-selling self-cultivation books. These two volumes are a compilation of texts he contributed to Jitsugyo no Nihon every month. The self-cultivation discourse of Nitobe, an elite intellectual who was Headmaster of the First Higher School (currently, the University of Tokyo) and a teacher at Tokyo Imperial University, became part of popular culture. His students and colleagues (the elite) at the First Higher School were concerned and critical of his involvement with popular magazines. Even so, he continued to search out solutions for working youths (the non-elite) to acquire the practical principles and skills to make their way in the world. He feared that self-cultivation would become a rush toward making money and personal advancement for youths who were not well educated.

A practicing Christian, Nitobe’s rules for life are dotted with Bible quotations and expressions with a Christian flavor. But he also quotes Shinto, Confucianism, waka poems, even the Emperor’s poems and Imperial Rescripts, advocating a unique form of self-cultivation where he distinguishes between Christianity and the other approaches, or sometimes combines several approaches. He says that self-cultivation is to practice virtue and to nurture the mind, and that to lead a virtuous life is a form of Confucian self-denial. But, when he explains what nurturing the mind means, he quotes what Jesus said to his disciple Peter, so he advocates a form of self-cultivation that is a mix of old and new, West and East. Using traditional terms and expressions that even rural youths would accept without resistance, he disseminated religious maxims for the new age (Takeda Kiyoko, Dochaku to haikyo [Indigenization and apostasy]). By publishing in popular magazines, he freed the youth from the secular values of making money and personal advancement and gave life a religious dimension. Rather than abstruse interpretations of the Bible, he discreetly incorporated religious mystique and succor into the art of making one’s way in everyday life. This is probably why his theory of self-cultivation appealed to many readers.

The youths at the First Higher School were also greatly inspired by him. In their exchanges with him, Watsuji Tetsuro (moral philosopher, 1889–1960), Abe Jiro (philosopher, 1883–1959), Abe Yoshishige (philosopher, 1883–1966), and other elite students discovered kyoyo (intellectual cultivation). Taisho kyoyo shugi (Taisho elite intellectual cultivation), a new path for improving one’s character, was formed when students in search of their identity as members of the elite compiled lists of the forms of knowledge to be acquired for the practice of intellectual cultivation. Many of the books on the reading list discussed the Bible, Buddhist scriptures, and religious thought. The students learned and accepted religion as part of intellectual cultivation, which is an example of how people at the time approached religion for reasons of self-reformation rather than faith.

Subsequently, intellectual cultivation was influenced by Marxism and militarism and remained a part of the elite student culture until the decade from 1965 to 1975. The publisher Iwanami Shoten supported intellectual cultivation, which is to build character through reading, while the cultural publications of Kodansha Ltd. were intended for the self-cultivation of working youths. A gap opened up between intellectual cultivation and self-cultivation where intellectual cultivation was something to be acquired by the educated elite, while self-cultivation was popularized as youth movements, corporate training, or everyday practices.

The Future of Self-Cultivation

In fact, the self-cultivation boom in modern Japan was richly varied, ranging from cold-water bathing, Zen meditation, meditation, reading, even savings. Some people engaged with self-cultivation to succeed in a competitive society, while others were searching for ways to lead their lives. Self-cultivation was the product of the search for a new self in the new era of Meiji, but it became associated with the atmosphere of totalitarianism during the war and is rarely used today. However, people still continue with their self-help efforts. Even though the approaches have changed with the times, self-cultivation emerges out of similar soil and seeds to blossom differently in each age. As was the case with self-cultivation, thoughts and actions that encourage self-improvement are often associated with religious beliefs in other forms than faith. Self-development books advocate success through positive thinking. Kondo Marie, chosen by TIME magazine as one of the 100 Most Influential People in 2015, refers to tidying up as a festival or a ritual and explains that your life will change forever if you reexamine yourself by looking at the things you own (The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up). While maintaining a cautious distance from religion, it seems unlikely that people will stop with self-improvement for purposes of success or self-development any time soon.

Translated from “Shuyo bumu ga umidashita choryu: Kindai Nihon no jibunmigaki (The Trends Created by the Self-Cultivation Boom: Self-Improvement in Modern Japan),” Chuokoron, August 2021, pp. 38-45. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [November 2021]

[1] A Western-style building constructed in 1883 in Tokyo for entertaining foreign diplomats and dignitaries

Keywords

- Osawa Ayako

- Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

- self-cultivation

- self-improvement

- shuyo

- Matsushita Konosuke

- PHP Institute

- Peace and Happiness through Prosperity

- Suzuki Seiichi

- Duskin Corp.

- Ittoen

- Prayerful Management

- Heart Sutra

- zazen

- meditation

- self-development books

- Saigoku risshi hen—Genmei jijoron

- Self-Help

- Samuel Smiles

- Murakami Shunzo

- Seiko Zasshisha

- Seiko (Success)

- Orison Swett Marden

- Nitobe Inazo

- Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha, Ltd.

- Kondo Marie