Anatomy of Tokyo University Graduates: Meritocracy and Gender Gap

Akamon Gate (Goshuden-mon of the former Maeda Clan’s Residence, build in 1827) is the symbol of the University of Tokyo

Photo: MUSASHI/Photolibrary

Honda Yuki, Professor, Graduate school of Education, University of Tokyo

What is condensed into the University of Tokyo?

The University of Tokyo. Needless to say, it is the oldest university in Japan and one of the top universities in Japanese higher education with a clear hierarchical structure such as difficulty of admission and prestige.

Tokyo University is often held up as the embodiment of the so-called “meritocracy” (often translated as “merit-based system” or “abilityism” in Japanese) through various means such as television talk shows, quiz programs, and its track record of students having advanced to high schools and preparatory schools.

However, reconsideration of the meritocracy itself is also progressing. In April 2019, Ueno Chizuko [Professor Emeritus of the University of Tokyo, chief director of the NPO Women’s Action Network (WAN)] drew attention with her words at the matriculation ceremony of the University of Tokyo. She said, “The fact that you can feel that your hard work will be rewarded is due to the environment (not the result of your efforts).” In 2021, a book by Professor Michael J. Sandel of Harvard University discussing the harmful effects of meritocracy was published under the Japanese title Jitsuryoku mo Un nouchi: Noryokushugi wa seigika? (word-for-word translation: skill is also a matter of luck — is meritocracy justice?; original title, The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?)” (Hayakawa Publishing).[i] In this book, Professor Sandel critically examines the drawbacks of meritocracy. He argues that a meritocracy, where positions and income are determined based on signals of “excellence” obtained from privileged backgrounds, justifies the social exclusion of those deemed “not excellent” and exacerbates societal divisions. One can view the University of Tokyo as a place that sends out the “winners” of such a meritocracy into society.

On the other hand, the University of Tokyo is frequently discussed in the media for rather unfavorable matters. Declining positions in international university rankings, an increase in enrollment from certain combined junior and senior high schools and from the Tokyo metropolitan area, research misconduct, harassment, and the punishment of teachers and students for sexual crimes. In particular, the gender imbalance in the number of female students and faculty members is an undeniable problem facing the University of Tokyo.

The needy who are neglected in the name of educational disparity and “self-help,” the meritocracy manifested in such a form, and the conspicuous gender gap in politics and the economy, are serious issues that permeate Japanese society as a whole. It is necessary to examine how they are condensed at the University of Tokyo based on data. This is because graduates who go out into society through the University of Tokyo are highly likely to be in positions of great authority and responsibility in the government, public administration, or companies. They are also the ones who determine the framework of this society in the form of laws, systems, and operations. It is meaningful, even if only partially, to clarify what kind of lives the University of Tokyo graduates have spent before, during, and after graduation, and what kind of thoughts they have.

And although female graduates are certainly a minority for the University of Tokyo in terms of proportion, they are the “winners” in Japanese society in terms of meritocracy. That they are such a twisted presence is also an important point. What kind of process did they go through to enter the University of Tokyo, and how do they live in a society filled with various difficulties that await women after graduation? By clarifying the actual image of these female graduates, we will be able to obtain useful suggestions for correcting the bias in the gender composition ratio at the University of Tokyo.

However, with the exception of a few cases of graduates of specific faculties and individuals with specific attributes, very few full-scale social surveys have been conducted on graduates of the University of Tokyo.[ii] There are some reports based on research and interviews, but they are limited to case studies and have not been able to quantitatively clarify the trends of the University of Tokyo graduates.[iii]

Therefore, in Fiscal Year 2022, the author conducted a comprehensive questionnaire survey targeting University of Tokyo graduates. For the survey, we set up a survey screen on the web, and sent the URL to approximately 60,000 alumni whose e-mail newsletter was distributed by the Alumni Section of the University of Tokyo’s Social Collaboration Headquarters, asking them to respond. The survey period was from November 9, 2022 to January 31, 2023, and the question items included work situation, family situation, life before entering the University of Tokyo, life during school, and opinions on society.

The total number of respondents was 2,437, and due to the small response rate, representativeness was not ensured, and the results presented in this paper remain provisional. As mentioned above, questionnaire surveys of the University of Tokyo graduates have been limited to specific departments and attributes, so it is certain that the data is valuable. Of the 2,437 respondents, 1,788 graduated from the University of Tokyo (bachelor’s course), and 1,768 of them are of Japanese nationality. 329 were female, 1,448 were male, and 11 did not answer their gender. There is a possibility that the 11 respondents who chose not to disclose their gender are sexual minorities. While sexual minorities are an important group, they form a minority of our respondents. Since there are many restrictions to see the distribution of various variables, this paper compares men and women. Approximately two-thirds of the female respondents belonged to “humanities and social sciences: HSS” departments (law, liberal arts, economics, humanities, and education) when they were enrolled at the University of Tokyo. On the other hand, more than half of the men were enrolled in “STEM” departments (engineering, science, medicine, agriculture, medicine).

In the following, male and female graduates of the University of Tokyo are the subjects of analysis, [iv] and from the survey results, we will show our findings on gender differences among the University of Tokyo graduates. Again, it should be noted that the figures shown in the following paper are only the results from the respondents of this survey.

Status before and during enrollment at the University of Tokyo

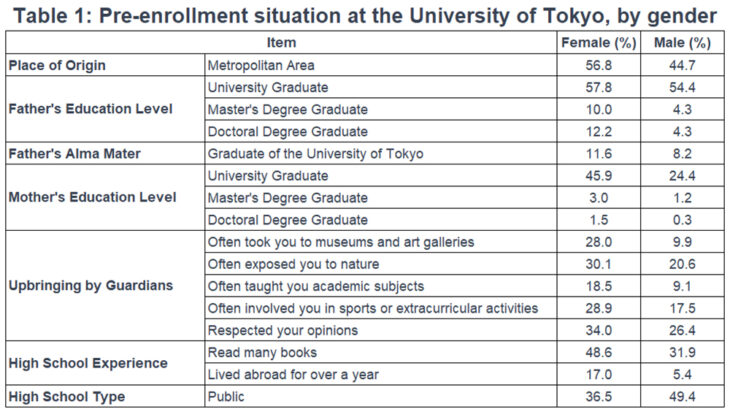

First, Table 1 shows the items in which there was a clear difference between men and women regarding the situation before entering the University of Tokyo.

What Table 1 suggests is that women come from families with a higher social status and cultural capital compared to men. Women are more likely to be from the Tokyo metropolitan area, have parents’ with an educational background, have parents who are enthusiastic about education, read a lot, have overseas experience, and have attended private or national high schools. It is possible for women to go on to the University of Tokyo, supported by abundant resources in the family background and upbringing history.[v] Conversely, a relatively large number of men graduated from local or public high schools. Compared to women, many of them went on to the University of Tokyo based solely on their academic performance up to high school. In order for women to break through the barrier of minority at the University of Tokyo, it can be said that they need the support of various resources and background factors in addition to their academic performance. In other words, it can be interpreted that women who lack these conditions face higher psychological and social hurdles to enter the University of Tokyo.

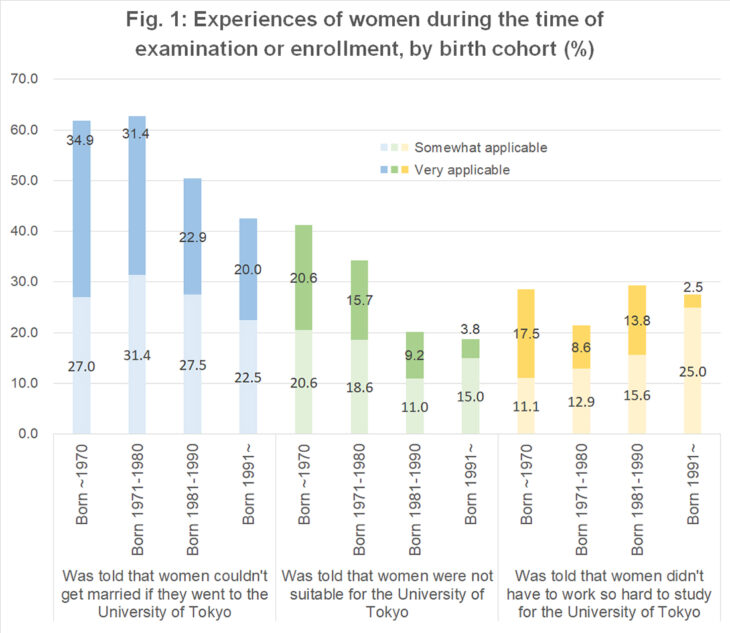

Fig. 1 shows part of the obstacles that stood in the way of women entering the University of Tokyo. In particular, older women have experienced many negative messages from those around them, such as, “If you go to the University of Tokyo, you will not be able to get married” and “Women are not suitable for the University of Tokyo.” Although this trend is declining among younger generations, we can see that there is still a sense of incongruity in Japanese society between the attribute of being a woman and the intellectual excellence symbolized by the University of Tokyo.

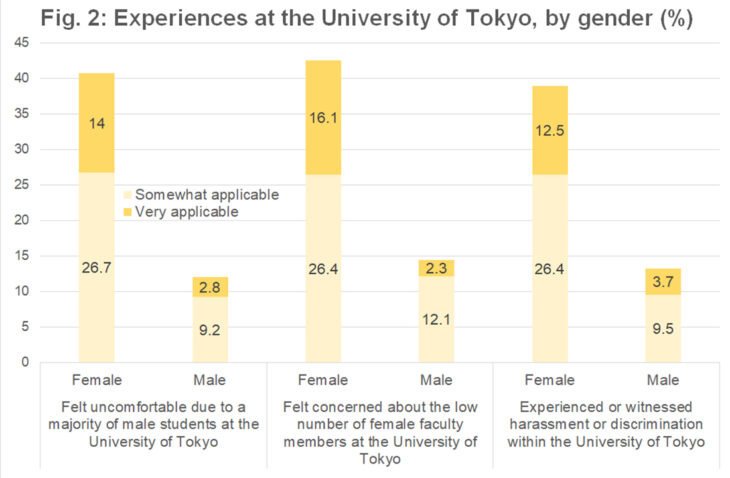

When asked about their experiences during their time at school after entering the University of Tokyo, female students had a higher positive rate than male students, with comments such as, “I actively took a wide range of classes outside of my major” and “I had the opportunity to fall in love with a student at the University of Tokyo.” However, in the items shown in Figure 2, there was a marked difference by gender.

Approximately 40% of females answered that they felt uncomfortable due to the lack of female students and faculty on campus, as well as experienced harassment and discrimination. In contrast, the figure is only around 10% for men. They graduated and completed their studies while avoiding feelings of alienation or experiencing any aggression on campus.

The gender gap in work

Then, what is the situation after entering society? More than 90% of both men and women are working in some form, excluding those who have reached mandatory retirement age. Nearly 90% of men are full-time employees, and the older they are, the more managers/executives, the more self-employed/free traders. The ratio of full-time employees is also 90% among young female graduates. However, as female graduates move into their 30s, 40s, and 50s, the number of full-time employees decreases to 80%, 70%, and 60%, while diverse forms of employment increase. Regarding occupational categories of young people, over 20% of both men and women are engaged in professional occupations. For women, clerical positions account for 40%, and for men, clerical positions and technical positions each account for just over 20%. As they get older, the number of women in professional positions increases and becomes the majority, and the number of men in managerial positions increases, reaching 30% for those in their 40s and older.

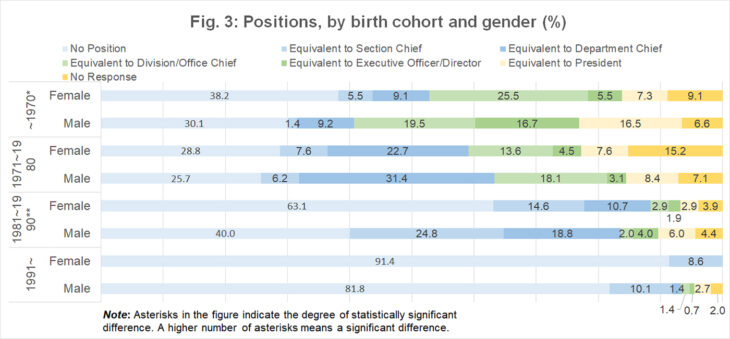

The job titles shown in Figure 3 show the gender gap. Among young people, 90% of women and 80% of men are “not in a managerial position,” so the difference between them is small. However, among those in their 30s, the percentage of those who do not have a managerial position is 60% for women and 40% for men, and the gap widens. In the oldest age group, there is a large gap between men and women in the percentages of high-ranking executives such as “equivalent to president” and “equivalent to senior managing director/director.” The situation of the oldest age group reflects that women are more likely to have professional occupations that are not related to job titles. However, the difference in job title rates among people in their thirties, who do not have many professional occupations, should be seen as an indication of gender inequality.

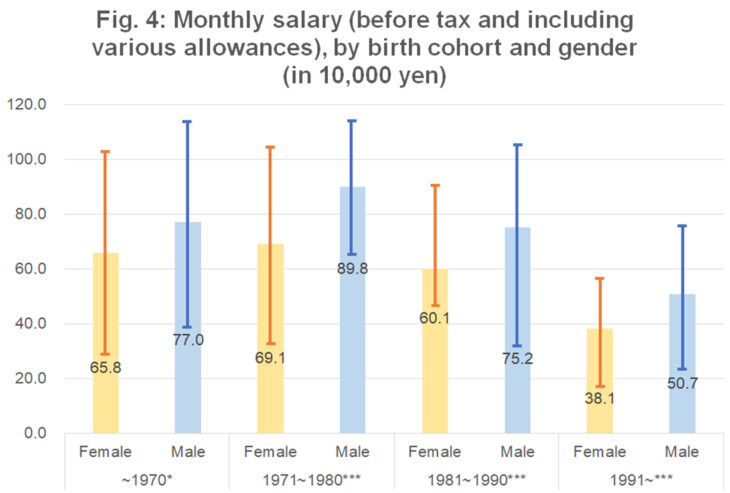

These disparities are also reflected in income. As can be seen in Figure 4, which shows monthly income by age group and gender, income levels differ between men and women who graduated from the same University of Tokyo. Compared to the wages of university and graduate school graduates in Japan as a whole, as seen in the Basic Survey on Wage Structure, the levels in Figure 4 can be said to be considerably higher for both men and women who graduated from the University of Tokyo. However, partly because of the above-mentioned disparity in positions, the fact that women earn less than men, even though they graduated from the same university, shows just how deep the gender gap is in Japan.

Family Formation

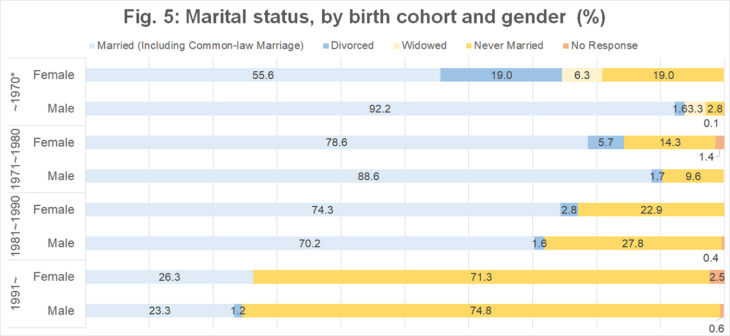

The state of the family is two sides of the same coin with this gender gap at work. First, as a basic situation, we confirmed the marital status (Fig. 5). Excluding the fact that a certain percentage of women born before 1970, the oldest group, are unmarried or divorced, the unmarried rate of male and female graduates of the University of Tokyo is lower than the unmarried rate of university and graduate school graduates in Japan as a whole, as determined by national census data. The high unmarried rate among the youngest is a trend across Japan due to late marriage, and is not limited to Tokyo University graduates. The idea in one of the items in Figure 1, “women couldn’t get married if they went to the University of Tokyo,” is a thing of the past, and at least in recent years it can be said to be no longer true.

In this survey, we asked married people about their criteria for choosing a spouse. The results show that, in general, women place more importance on a variety of factors, such as closeness in values, economic power of the partner, work, educational background, appearance, education, respect for one’s own work and opinions, and housework ability. In fact, women are more likely than men to have regular discussions with their current spouses. At the same time, however, women are more likely to give priority to family than work. Men are more likely to have their spouses responsible for housework. About half of the male University of Tokyo graduates have unemployed spouses (full-time housewives), while more than 90% of the spouses of women who graduated from the University of Tokyo have a job. At least half of the males who graduated from the University of Tokyo can leave housework and childcare to their spouses and concentrate on their work, whereas females who graduated from the University of Tokyo continue to mainly take on household responsibilities while having a job. These differences are thought to be reflected in the aforementioned gender gaps in job titles and income.

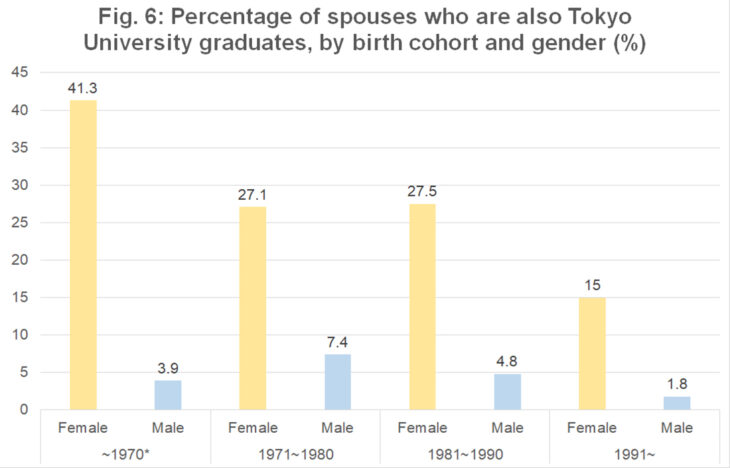

In addition, 27% of female University of Tokyo graduates who have spouses also have spouses (husbands) who are University of Tokyo graduates. This ratio is clearly higher than the 4% among male University of Tokyo graduates. As shown in Figure 6, this ratio among women is high among the older generation and is decreasing among the younger generation, but the fact that women are a minority on campus means that there are many potential spouses around them. However, since such college assortative mating is also a trigger for social closure and reproduction of social inequality, it may be said that it is desirable that this trend is weakening.

Attitudes towards Society

Finally, let’s take a look at what kind of social views they have today.[vi]

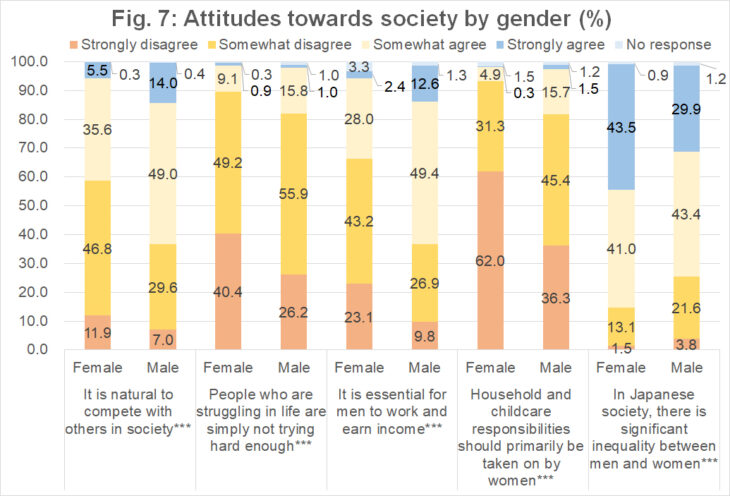

As shown in Figure 7, there are clear differences between men and women in the following items: “It is natural to compete with others after entering society,” “People in poverty are not trying hard enough,” “It is important for men to work and earn an income,” “Housework and childcare should be mainly done by women,” and “There is too much inequality between men and women in Japanese society.” Male University of Tokyo graduates have a higher degree of affirmation of competition and effort, and a higher degree of support for male earning roles and higher degree of support for women’s family roles than females. Conversely, recognition of the gender gap in Japanese society is relatively weaker among men than among women. The propensity to endorse meritocracy and traditional gender roles is particularly pronounced among older men, while the difference between men and women is not as great among younger generations. The gender gap in responses to these items is confirmed in many social surveys, not just among University of Tokyo graduates. However, the fact that such tendencies can be seen clearly among older men who have graduated from the University of Tokyo, who have a high probability of attaining power, influence, and financial power in society as typical winners of meritocracy, may hinder a drastic reexamination of the problems of meritocracy and the stereotyped gender roles in Japan. If the University of Tokyo aims to avoid being criticized for perpetuating negative practices, it will be necessary to take steps towards reviewing and reforming educational content and the university’s stance to fulfill its “product liability.”

Conclusion

In addition to the differences between men and women shown in this paper, there are many other axes that divide the University of Tokyo graduates, such as whether they graduated from a combined junior and senior high school or not, and what academic field they majored in at university. The families of combined junior and senior high school graduates are of high social class, and there is a strong tendency to enter the University of Tokyo for the purpose of practical profit. They enjoy student life while they are in school, and there is a high probability that they will have a high income after graduation. So-called “STEM” graduates are enthusiastic about their specialized field of study, but their social interest is weaker than “HSS” graduates. And there is a high probability that women from “STEM” have experienced or heard of harassment. Due to space limitations, I have no choice but to leave the details of these results for another article, but needless to say, it is necessary to clarify through further research and analysis that the University of Tokyo graduates are not monolithic, and that each subgroup has its own unique characteristics and issues.

Returning to the issue of gender examined in this paper, the female graduates of the University of Tokyo represented in the survey data this time were supported by abundant family resources—which also means the reproduction of social classes—and enrolled at the University of Tokyo, where they actively learned while experiencing issues of minority discrimination and harassment. After graduating, many of them have jobs and families, and lead satisfying lives. However, their careers reflect Japan’s deep-rooted gender gap, as they fall behind men who graduated from the same university in terms of income and job titles due to family responsibilities. Perhaps because of these conflicts, the female University of Tokyo graduates are not as strong as the male University of Tokyo graduates in remorselessly praising competition and effort.

Men, on the other hand, entered the University of Tokyo as the winners of the entrance examination competition from all over the country based on the meritocratic criteria of academic achievement, even though they were blessed with a better environment than society as a whole. And many of them, from the position of the majority of the campus, go out into society without being aware of the gender gap or harassment on campus, leave most of the caregiving role at home to their spouses, acquire higher status as they get older, and exercise their influence in society with a deep sense of affirmation of competition and effort.

The trends in the survey data suggest that the University of Tokyo, as it is today, needs to reflect on its current status as a stronghold of meritocracy and the gender gap. It is necessary to transform the University of Tokyo into a place where diversity and inclusion reside not only in terms of gender but also nationality and the presence or absence of disabilities. Drastic reforms are also needed in the way of allocating the majority of successful applicants to general entrance exams, which has been regarded as a sanctuary until now, and in the establishment of courses in the first semester, which maintains traditions from before the war.

The administration of the University of Tokyo is aware of the current problems, and has begun efforts such as research and education related to diversity within the university. However, the bias in attributes among students and teachers still remains remarkable. As a recent development, the on-campus student group “#YourChoiceProject” conducted its own survey targeting high school students and announced the results of a survey that clarified the characteristics of career choices for female high school students living in rural areas.[vii] From these new surveys and a more detailed analysis of the current survey of University of Tokyo graduates, it is essential to continue to make efforts to shed light on the problems of the University of Tokyo and of Japanese society, and to implement corrective measures based on those problems.

Translated from “‘Todai-sotsu’ wo kaibosuru: meritokurashii to gendaa gyappu no sakuso (Anatomy of Tokyo University Graduates: Meritocracy and Gender Gap),” Sekai, July 2023, pp. 52-62. (Courtesy of Iwanami Shoten, Publishers) [August 2023]

Keywords

- Honda Yuki

- Graduate school of Education

- University of Tokyo

- meritocracy

- gender gap

- merit-based system

- societal divisions

- educational disparity

- diversity

- Ueno Chizuko

- Michael J. Sandel

- social status

- cultural capital

- harassment

- discrimination

- family

- marital status

- income