Beyond the COVID-19 Crisis: Hurry to Reach an Agreement on the “Burden” to Rectify Disparities

Yoshikawa Hiroshi, President, Rissho University

Key points

- Postwar social security developments have contributed to longer life expectancy

- Disparities are a mix of transient phenomena and long-term trends

- It will be difficult to sustain social security with the current national burden rate

(Discuss Japan Note: This article was written before the sixth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic hit Japan)

Prof. Yoshikawa Hiroshi

The COVID-19 pandemic has subsided in Japan, but the situation remains unpredictable as the emergence of new variants and global re-spread may still occur.

Over the past two years, the world’s economy and society have been at the mercy of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, the global economy fell into a severe recession that exceeded the post-Lehman shock fall in 2008. When the first state of emergency was declared in the spring of 2020, Japan saw the biggest fall in GDP in the postwar period.

Amid such circumstances, there is renewed attention on the disparities that have been a problem since the late 20th century. This is because the economic downturn has had a major impact on non-permanent workers and the small and medium-sized service industries. The core of the government’s economic measures has also been benefit payments to help the vulnerable and small and medium enterprises.

Apart from its immediate impact, the COVID-19 pandemic is having a permanent impact on our economy and society. The Kishida administration has advocated “new capitalism.” In this paper, I would like to consider the roles of infectious disease, capitalism, disparities, and the government from a historical perspective.

The relationship between infectious disease and humanity goes back to prehistoric times. Japan has been hit by repeated plagues since ancient times. As suggested by the promotion of avoiding “the three Cs” (closed spaces, crowds, and close contact)” during the current pandemic, infectious diseases spread where people gather. Such spreads happened in big cities like Tokyo and Osaka.

In the last few millennia, land has been indispensable to agriculture as the foundation of the economy, so it has been necessary for people to spread out geographically. However, it was industry that led the modern capitalist economy, which came about in the 18th century through the Industrial Revolution. With the rise of industry, people concentrated in the cities because agglomeration is more advantageous, as opposed to how it works in agriculture. Over the past 200 years, the development of the advanced economy has also been a history of urbanization.

Since the birth of the capitalist economy, it has grown alongside the risks posed by infectious disease. Of course, rising income levels associated with economic development have improved people’s health through better housing and eating habits as well as improved medical technology, but this progress was never single-track.

For example, in 1900, when Natsume Soseki, a well-known Japanese novelist, studied in London, the average life span in Britain and Japan was 45 and 43 years, respectively, which is pretty much the same level. Japan’s per capita income, on the other hand, was about a quarter of that of Britain, one of the highest in the world. The reason why the average life span of Japan, a country with incomes lower than those of Chile and Mexico, was at the same level as that of Britain is because industrialization was under way in Japan and most Japanese people were rural farmers. In Britain, the favorable condition of a high income level was counteracted by the concentration of people in cities with underdeveloped public health.

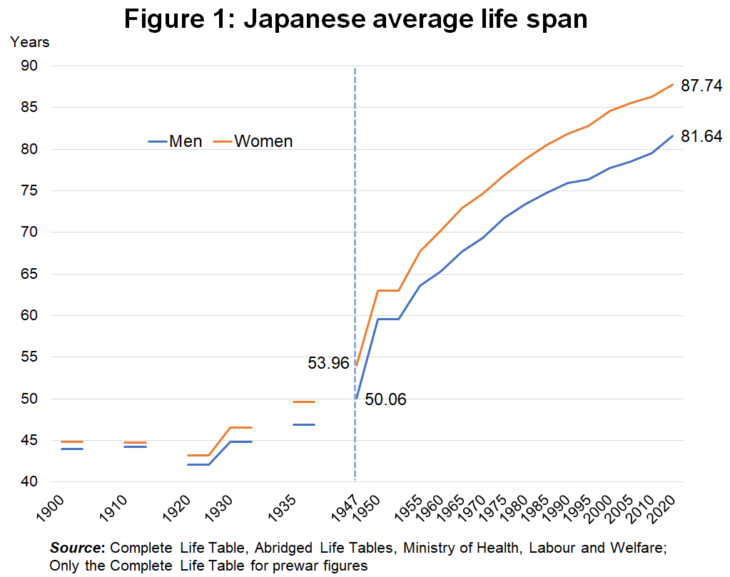

In the developed countries in North America and Europe in the first half of the 20th century, the average life span steadily became longer thanks to economic growth, the development of public health, and advances in medicine. However, the Japanese average life span did not become much longer in the prewar period (see Figure 1). The Meiji government initially promoted improvements in basic public health, but starting in the beginning of the 20th century, its sole focus was on strengthening armaments while neglecting better water supply, sewerage, and medical care systems. In the prewar period, there were few “social burdens” to fund social security, which is why Japan’s average life span stagnated before the war.

In 1947, shortly after the war, Japan’s average life span was 50 years for men and 54 years for women, the shortest among developed countries. But now, at 81.6 years for men and 87.7 years for women, Japan has become one of the most longevous countries in the world. The background of longer life spans in the postwar period was not only economic growth and advances in medical technology but also the development of a social security system, including pension/medical insurance.

The development of capitalism, which began in the 19th century, has also been a history of struggling against “disparities.” Disparities in industrial-centered capitalist society were much larger than those in traditional rural areas. Describing this as an irreparable system flaw and advocating a shift to socialism, Marx and Engels wrote Communist Manifesto in 1848.

Against this backdrop, developed countries in Europe developed social security systems as “breakwaters against disparities” from the end of the 19th century into the 20th century. Thus, the “Night-watchman state,” where the government only played a minimal role in law and diplomacy, disappeared 150 years ago. The capitalist economy, as a new 20th-century economic system where the government actively handles income redistribution, was referred to as a “mixed economy” by economist Paul Samuelson. This really was the birth of “new capitalism.”

Having said that, the problems of disparities remained unsolved. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has once again highlighted the problems of disparities. Yet the disparities we see before us are a mixture of disparities temporarily amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic and historical trends that have occurred over decades. It is easy to give too much attention to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the bigger problem is the historical trends such as the declining birthrate and aging population.

Longevity is a marvelous thing, but at the same time, there are much larger disparities among the elderly than the working generation in terms of income, assets, and health conditions. The aging society is also a disparate society. One in five elderly people lives alone. Their own efforts at self-help alone cannot solve this problem.

The Kishida administration is striving to achieve a “virtuous cycle of growth and sharing.” The short-term logic of this is “sharing” in the sense of distributing benefits to stimulate consumption and promote growth. But fears about the future of social security have caused most of the benefits to go to savings rather than consumption. The same goes for the wage increases that the administration is wanting to see. Even if wages are increased as intended for one year, the impact on consumption will be limited unless households really feel that there is a rise in permanent income. If long-term problems are not solved, it will be impossible to create a “virtuous cycle” even in the short term.

It is economic growth that creates a rise in permanent income. Innovation is the source of economic growth, especially the kind of growth that raises per capita income. John Maynard Keynes proclaimed the vitality of the innovation-producing private sector as animal spirits. The government’s job is not to let “growth strategy” end as a mere rhetoric, but to execute it promptly.

Income redistribution to suppress disparities is necessary for social stability. History teaches us the heavy lesson that no country has prospered with a struggling middle class. In Japan, the evening out of disparities is also a necessary condition to put a stop to population decline.

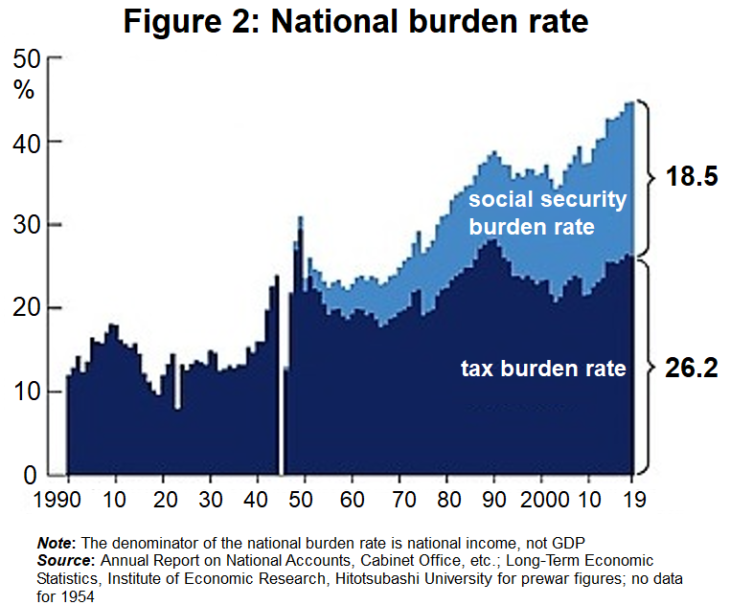

Taxation and social security reduce medium- to long-term disparities in capitalist society. Needless to say, a corresponding burden must be borne in order to maintain systems such as pension, medical, and long-term care insurance. Looking at the tax burden of postwar Japan in terms of national income ratio, it has generally been at a stable level, but the “social security burden rate,” such as social insurance premiums, started from zero and has risen to 18.5% in recent years (see Figure 2).

The combined national burden rate is 44.7%. Looking at major European countries, the national burden rate is 48.6% in Britain, 55.8% in Germany, and 68.0% in France. Meanwhile, the most recent aging rate (percentage of the population aged 65 years and older) is 29.1% in Japan, 22.0% in Germany, 21.1% in France, and 18.8% in Britain, which makes Japan an aging front-runner.

The current national burden rate cannot sustain social security. Although it is somehow supported through public funds, tax revenues are chronically insufficient, which translates to financial deficits. The public debt-to-GDP rate has doubled. The government’s most important task right now with regard to “sharing” is to form social consensus on “burden,” and this is something only the government can do.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 4 January 2022 under the title, “Korona-kiki wo koete (I): Kakusazesei eno ‘futan’ goi isoge (Beyond the COVID-19 Crisis: Hurry to Reach an Agreement on the “Burden” to Rectify Disparities)).” The Nikkei, 4 January 2022. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Hiroshi Yoshikawa

- Rissho University

- social security

- life expectancy

- disparities

- national burden rate

- tax burden

- social security burden

- COVID-19

- infectious disease

- recession

- “new capitalism”

- “growth and sharing”

- capitalist economy

- life expectancy

- public health

- wages

- social consensus

- government