The Contest for Economic Hegemony in Asia: With a focus on rules on digital trade

Kawashima Fujio, Professor, Kobe University

Key points

- The Asia-Pacific as a main battleground for digital trade

- The US and China fighting for control over the rules

- Japan ought to actively participate in rule-making as a matter of national interest

Prof. Kawashima Fujio

The United States and China are engaged in fierce fighting for control over rule-making on digital trade in the Asia-Pacific region.

In September and November 2021, China applied to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) which has an advanced chapter on electronic commerce and the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA). By contrast, in October, the United States announced that they would start building the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) in 2022. Moreover, in January 2022, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) for East Asia, which also has a chapter on electronic commerce, entered into force among Japan, China, and eight other countries.

While some do not see China’s joining the CPTPP and the DEPA as anything more than small disturbances and suspect its seriousness, others see it as steps toward the creation of the Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP). Meanwhile, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework Initiative (IPEF Initiative) of the US does not specify the areas covered or what it ultimately aims to achieve, so its feasibility remains questionable.

Firstly, why is the focus on digital trade and why the Asia-Pacific region? According to 2020 data from the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the amount of global cross-border data has increased nearly fivefold in five years, with about half of that occurring in the Asia-Pacific region. It makes sense that the United States and China, who are both great powers in the digital economy, would engage in a fight over control when we consider how the rules on digital trade for the region may affect the global economy.

Next, what is China hoping to achieve by joining the CPTPP and the DEPA? With regard to the CPTPP, “China and CPTPP: An analysis on the policy documents issued by China regarding the entry to Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)” (Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry [RIETI], 2021) co-authored by Professor Watanabe Mariko, Gakushuin University and me, et al., it appears that China is trying to acquire and strengthen “institutional discourse power” for the sake of creating the FTAAP. It should be possible to regard China’s joining the DEPA along a similar line of thought.

It is very likely that China believes it is easier to manage the DEPA members Singapore, New Zealand, and Chile than the CPTPP members such as Japan, Australia, and Canada.

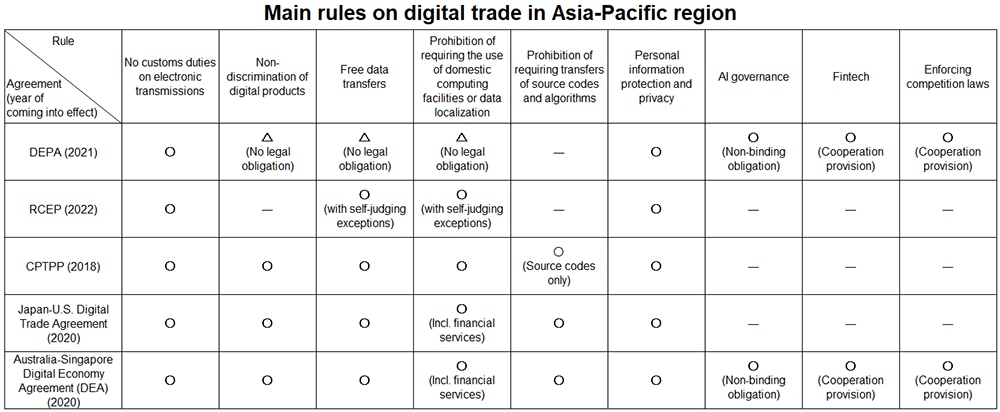

Moreover, when it comes to ensuring free cross-border data traffic and prohibiting data localization or requirement to use domestic computer facilities, the DEPA rules simply affirm the corresponding CPTPP regulations without imposing any legal obligations. Likewise, there are no regulations prohibiting demands to transfer algorithms and “source codes,” which are software blueprints. China enacted three data laws (Cybersecurity Law, Data Security Law and Personal Information Protection Law) in 2021, but it is dubious whether they will be able to abide by these regulations.

Meanwhile, the current DEPA has wide-ranging provisions on AI governance frameworks, fintech and digital platform competition, which should be areas that China is very interested in, but there remain many uncertainties about how these disciplines will develop in the future (see table).

Overall, China’s application for DEPA membership is likely based on an expectation that they can take the initiative while avoiding rules that are unfavorable to themselves and exert a strong influence on the direction of rule development.

Meanwhile, the scope and feasibility of the US IPEF initiative remains unknown. If we look at the information from administration tops and the US Congress, it will almost certainly include digital trade, while tariff reductions on goods are not on the table. Many argue that the Japan-United States Digital Trade Agreement and the Australia-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement (DEA) (see table) should serve as models.

The emphasis on “shared values of democracy and human rights” in the statements from the Japan-Australia-India-US (Quad) Summit, the US-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC), G7 Trade Ministers’ Meetings, and elsewhere in September to October 2021, may also become apparent in parts of the IPEF Initiative that relate to digital trade. It is possible that they will include rules that practically exclude China and other countries that do not share the same values, such as opposition to digital authoritarianism, data free flow with trust (DFFT), trusted government access (access to personal data by governments), and reliable AI development and use.

China is increasingly wary of US containment. They announced the Global Data Security Initiative in September 2020 in response to the Clean Network Project already launched at the time of the Trump administration. While aiming for an open, equal, and non-discriminatory environment for digital economic development, they have also indicated that they will protect data security.

President Xi Jinping’s speech at the G20 summit meeting in October 2021 also touched on the initiative just before announcing the decision to apply for DEPA membership. China’s applications to join the CPTPP and the DEPA can be understood as a strategy to respond to the US containment of China by taking full advantage of the American absence from the TPP due to domestic circumstances.

So, is rule-making on digital trade really possible at a point when the United States and China are ruthlessly engaged in containment and anti-containment?

Notable multilateral moves related to this include the negotiations under the Joint Inntiative on Electronic Commerce (where the US, China, and 84 other countries participated), which has been underway since 2019, following the joint statement at the 2017 WTO Ministerial Conference.

According to the co-convenors’ statement on these negotiations in December 2021, opinions converged on relatively low-confrontation issues such as online consumer protection, electronic contracts, and electronic authentication. On the other hand, they did no more than consolidate the text proposals for free cross-border data traffic, data localization, source code transfer requests, and similar topics. The aim is to secure convergence on the majority of issues by the end of 2022, but I am not optimistic about how the negotiations will proceed.

It is true that recent developments suggest there being areas where American and Chinese policy seem to converge, such as strengthening competition laws and regulations for digital platform operators. On the other hand, when it comes to cracking down on public opinion manipulation, they have introduced regulations that reflect their respective governance systems and values, for example with China moving to tighten regulations on algorithm recommendations (drafted in August and enacted in December 2021).

If the United States is proposing for rules on digital trade to be designed based on “shared values” such as democracy and human rights, this could be a major obstacle to creating an FTAAP with China in it.

While both the US and China are actively moving toward rule-making on digital trade that is in their own interests and reflects their values, they are also cautiously selecting and designing groups and frameworks that do not touch on issues that are inconvenient to themselves. If the conflict between these two great powers in the digital economy, whose values are so starkly contradictory, deepens further, Japan might end up at their mercy.

Japan needs a vision for the future of the entire Asia-Pacific region. Will Japan move to expand the list of countries abiding by existing rules, such as CPTPP’s electronic commerce chapter and the Japan-US Digital Trade Agreement, for which the United States was the driver of rule-making, or will we propose our own rules that either transcend or adjust existing rules? Alternatively, will we dedicate ourselves to mediating between the US and China? It is necessary for Japan to be actively involved in rule-making on the basis of clearly discerning our interests with regard to digital trade.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 14 January 2022 under the title, “Ajia no Keizaihaken-arasoi (II): Dejitaru-ruru, Shoten ni (The Contest for Economic Hegemony in Asia (II): With a focus on rules on digital trade).” The Nikkei, 14 January 2022. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Kawashima Fujio

- Kobe University

- economic hegemony

- digital trade

- rules

- rule-making

- Asia-Pacific

- Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership

- CPTPP

- Digital Economy Partnership Agreement

- DEPA

- Indo-Pacific Economic Framework

- IPEF

- Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement

- RCEP

- AI governance

- Japan-United States Digital Trade Agreement