Abenomics and Kuroda’s Bazooka: Contemporary Historical Considerations

On February 28, 2013, Abe spoke about Abenomics in his policy speech at the 183rd Session of the Diet: “We will vigorously launch the ‘three prongs’ of economic revival, namely bold monetary policy, flexible fiscal policy, and a growth strategy that encourages private sector investment.”

Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Nakazato Toru, Associate Professor, Sophia University

Prof. Nakazato Toru

Abenomics came to an abrupt end without sufficient evaluation or summation. Its general form has continued in the economic policy of the Kishida Fumio administration, and it can be said that Abenomics is still ongoing, but there is no guarantee that this drama will continue as it has in the past without its leading actor. Concerns about a weak yen and high prices have also raised calls for a review of monetary easing.

It will take considerable time to take a step back and position Abenomics in history from an objective standpoint, but it would still be meaningful to record its trajectory so far together with the contemporary mood before memory fades. In this paper, as a small attempt toward this work, I look back on its development over the past 10 years or so.

1. Abenomics in 2013

Abenomics in 2012

When did Abenomics start? This is a difficult question. It officially began on December 26, 2012, when the second Abe administration was launched, but the flow leading up to Abenomics had already started in the fall of 2012. There were growing expectations for an economic policy shift through a change of government, so the move toward the yen’s depreciation and rise in stock prices was already in progress.

On February 28, 2013, Abe spoke about Abenomics in his policy speech at the 183rd Session of the Diet: “We will vigorously launch the ‘three prongs’ of economic revival, namely bold monetary policy, flexible fiscal policy, and a growth strategy that encourages private sector investment.”

Photo: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Prof. Nakazato Toru

Discuss Japan—Japan Foreign Policy Forum No. 73

In the presidential election of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) on September 26, 2012, three months before the second Abe administration came into being, Abe Shinzo defeated Ishiba Shigeru and was appointed the 25th President. Characteristic of this election was that Abe made overcoming deflation a top policy agenda and strongly advocated the need for “bold monetary easing.” It is generally held that monetary policy does not “translate into votes,” so it was an unusual move since this topic is not necessarily one of high interest in Nagatacho (Japan’s political center).

Under these circumstances, expectations for a big economic policy shift grew, and on November 16, 2012, when the Lower House was disbanded, stock prices started to rise and the Nikkei Stock Average, which had been hovering between 8,500 and 9,000 yen, recovered to the 10,000 yen mark by the end of the year, with the last session of the year (December 28, 2012) reaching 10,395.18 yen, which was the highest since the beginning of the year (stock prices rose 23% in one year, with more than 80% of that increase happening after November 16). It was the first time in seven years, since 2005, that stock prices had risen more than 20% in a year.

From “Joint Statement” to “unprecedented monetary easing”

The Abe administration began in earnest at the beginning of the year, and on January 22, 2013, the Cabinet Office (CAO), the Ministry of Finance (MOF), and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) jointly announced the “Joint Statement of the Government and the Bank of Japan on Overcoming Deflation and Achieving Sustainable Economic Growth.” This is because one of the campaign pledges in the Lower House election in 2012 was to “set a price target (2%) on par with the developed countries in Europe and North America through an accord between the government and BoJ.” During the course of policy adjustment, some of the parties involved expressed concern about the term “accord” and settled on the term “joint statement,” but the URL for the website of the Prime Minister’s Office clearly used the term “Nichigin Accord.” [1]

One month before this “Joint Statement” and three days after the voting day of the Lower House election (December 19, 2012), a book titled America wa Nihon keizai no fukkatsu wo shitteiru (America knows the revival of the Japanese economy) (Kodansha), written by Yale University Professor Emeritus and soon-to-be cabinet advisor of the Abe administration Hamada Koichi, and this became a topic of big discussion.

Thus, a basic framework was put in place, and the “bold monetary easing” came to be manifested as “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing” (QQE) by BoJ Governor Kuroda Haruhiko (decided at the Monetary Policy Meeting on April 4, 2013). Since then, QQE has come with various appendages, and the “unprecedented easing” is now like a hot spring inn on which numerous extensions have been built. “Quantitative easing” at this point was a simple measure for manipulating the monetary base, and its framework is a textbook example of macroeconomics (reminiscent of the IS-LM model’s “investment savings” [IS] “liquidity preference-money supply” [LM] curves).

The main content of the initial QQE policy was to conduct money market operations so that “the monetary base will increase at an annual pace of about 60–70 trillion yen,” to that end purchase JGBs so that “their amount outstanding will increase at an annual pace of about 50 trillion yen,” purchase “ETFs and Japan real estate investment trusts (J-REITs) so that their amounts outstanding will increase at an annual pace of 1 trillion yen and 30 billion yen respectively,” and through these measures “continue with the QQE, aiming to achieve the price stability target of 2 percent, as long as it is necessary for maintaining that target in a stable manner.” Measures such as an increase in asset purchases, negative interest on the BOJ’s Current Account Deposits, and control of short- and long-term interest rates were added to the framework. As such, the “bold monetary easing” continues to this day.

2. Consumption tax hike and unprecedented easing

“Unfounded optimism” over the unprecedented easing and the consumption tax hike

With regard to this history of Abenomics and unprecedented easing, we must not forget the continuing big discussion in different situations about how to balance the two policy objectives of overcoming deflation and fiscal consolidation. In particular, the consumption tax hike inherited from the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) administration (gradual increase in tax rate from 5% to 8%, 8% to 10%) has been a major focus. In order to overcome deflation, it is necessary to create an environment where the demand of the economy as a whole is strong enough to cause rising prices in the form of demand pulls. A consumption tax hike could lead to a downturn in the economy through a drop in consumption, which could hamper stable rising prices.

In this regard, many initially expressed the view that “since the effects of QQE are strong and will support the economy even if there is a minor shock, the negative effects of a consumption tax hike would be only temporary.” During an intensive series of hearings from a broad range of experts on the consumption tax hike held at the CAO on August 30, 2013, Governor Kuroda explained that monetary policy can be used to handle any downward turn in the economy due to the consumption tax hike, but that if interest rates soar due to the postponement of the consumption tax hike, then there are limits on the effectiveness of monetary policy, expressing the view that “delaying the consumption tax hike comes with a terrible risk.”

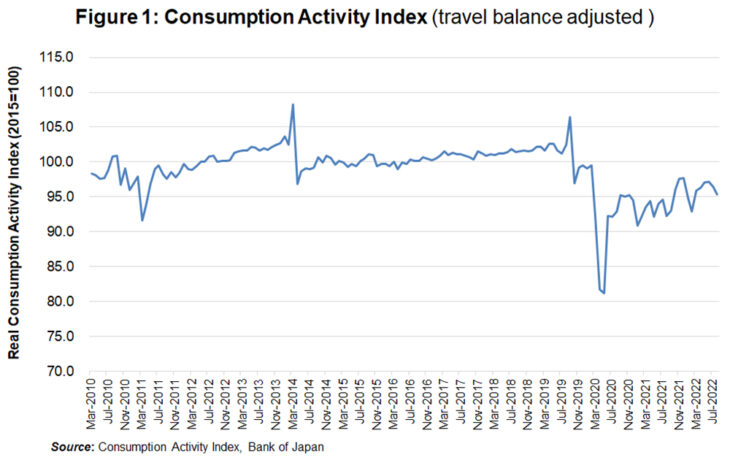

Before the consumption tax hike, it was expected that the effects of the reactionary decline would disappear in the summer of 2014 and that the economy would continue to recover steadily. However, consumption actually declined starting from the consumption tax hike and stagnated for more than three years (Fig. 1).

In the spring of 2014, the GDP gap turned to a plus (excessive demand), prompting policymakers to be optimistic about achieving the “2%” price stability target, but in reality, sluggish sales led to widespread price cuts among firms after the consumption tax hike, which coincided with the fall in oil prices that occurred in the summer of the same year to significantly slow the pace of rising prices. The “basic assessment” of Indexes of Business Conditions published by the CAO was revised downward in April 2014 “indicating a standstill,” after which it was further lowered “indicating a downward phase change” in August, leading to concerns about a return to deflation.

For this reason, in October 2014, BoJ implemented additional monetary easing, and in November the then Prime Minister Abe announced a postponement of the increase in consumption tax rate scheduled for October 2015 (from 8% to 10%). At the Upper House Research Committee on Deflation-Ending Measures and Strengthening Public Finance for Nationals’ Life held on May 13, 2015, Governor Kuroda spoke about the impact of the consumption tax hike, saying that “It was of a size that slightly exceeded expectations.”

In this way, Governor Kuroda, who emphasized the “terrible risk” of delaying the consumption tax hike, came to face “terrible risk” due to economic stagnation after the consumption tax hike and a slowdown to rising prices, making it difficult to achieve the “2%” price stability target. In September 2016, BoJ published a “Comprehensive Assessment” (Developments in Economic Activity and Prices as well as Policy Effects since the Introduction of Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing), explaining the reason for the failure to achieve the “2%” price stability target as being the major factors of “decline in crude oil prices,” “volatile global financial markets stemming from emerging economies,” and “demand weakened following the consumption tax hike.”

Increased employment and a decline in real wages

After the consumption tax rate was raised to 8% in 2014, consumption stagnated for a long time because wages were not increasing and it could not keep up with the pace of rising prices (note that the consumption tax hike is passed on to prices of products and services, resulting in an increase in prices including taxes).

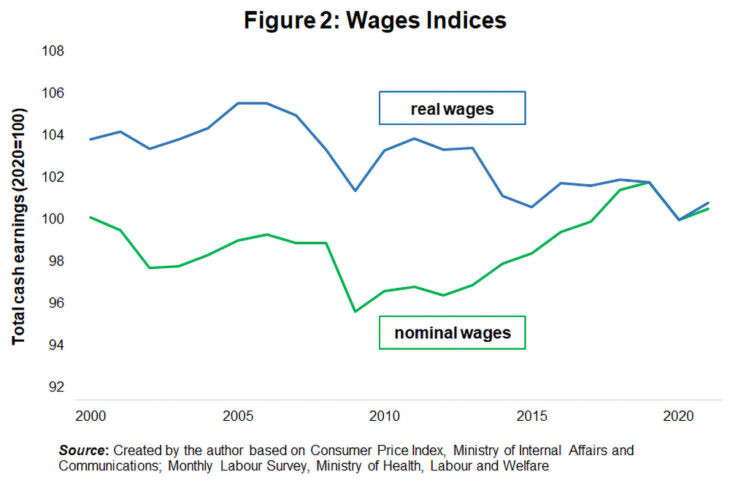

It was said that the sluggish wage increases were due to the increase in the number of workers with short working hours (since shorter working hours reduce wages, the average wages tend to fall as the number of workers with shorter working hours increases). Even if we only consider only full-time “regular workers,” real wages have remained almost unchanged after falling sharply in 2014 (falling further in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic) (Fig. 2). From 2013 to 2019, nominal wages continued to rise but real wages developed like this because there was no strong rise in nominal wages to exceed the rising prices.

Meanwhile, the number of employees continued to increase from 2013 to 2019 (increase by 4.7 million from 2012 to 2019), and the number of the unemployed decreased significantly (the number of the unemployed decreased by 1.23 million from 2012 to 2019). If we divide employees into regular and non-regular employees, it should be noted that about 70% of the increase was non-regular employees, but it is also true that their employment status improved significantly during Abenomics.[2]

“2%” remaining unachieved

Due to the impact of the rise in import prices because of the weak yen and the consumption tax hike, the increase rate of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) (year-on-year) including consumption tax from April to September 2014 exceeded 3%. However, these “high prices” were only temporary. Before the consumption tax hike, there were those who optimistically believed that the deflation could be overcome through rising prices in general from the increase in the consumption tax rate, but in reality, the rising prices caused a buying spree, and sluggish sales led to companies reassessing bullish pricing and slowed down the pace of rising prices.

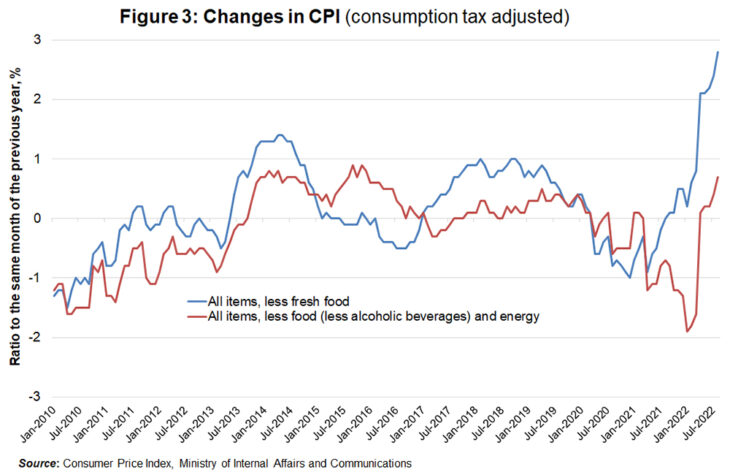

Looking at a basis excluding the impact of the consumption tax hike, it never happened even once during the Abe administration that headline (general) and core (general excluding fresh foods) CPI (yr/yr) reached 2%. The year-on-year increase rate of core-core (all-items excluding food and energy), which reflects underlying price trends, never reached 1% (Fig. 3). The deflation of continuously declining prices was eliminated to some extent, but the “2%” price stability target remained unachieved.

From April 2022 onward, headline (general) and core (general excluding fresh foods) CPI (ratio to the same month of the previous year) has reached 2%, and high prices rather than deflation became a major social problem. However, these rising prices are a local development that accompanies the surge of resource prices and the weak yen (however, since food, gasoline, electricity, and gas are daily necessities, their high prices have a major impact on people’s perception of inflation), with core-core (all-items excluding food and energy) prices hovering in the range of 0.0–0.5% (Fig. 3 above). Although some of the effects of the reduction in mobile phone charges still remain, the underlying trend in prices is not strong enough at this point, so by the time the effects of rising resource prices and weak yen have subsided, there is a possibility that prices will exhibit weak development due to economic stagnation just like in 2014 (note that resource prices have recently started to decline).

The illusion that “the Abe administration has a lax fiscal policy”

It is perhaps because the then Prime Minister Abe continued to take a proactive stance toward fiscal stimulus that the reputation that “the Abe administration has lax public finance” became entrenched. However, this is an illusion that arises from an impressionistic argument that does not properly check the financial results data and looks only at the budget figures. If we compare primary balance expenditures (= General Account Total Expenditure minus part of National Debt Service) and tax revenue trends between 2013 and 2019 with fiscal year 2012 (Noda administration), government spending has been almost flat (increased spending in 2019 was due to the economic measures to soften the impact of a consumption tax hike). Since tax revenues increased significantly during this period, the fiscal deficit was greatly reduced.

The target of fiscal consolidation, developed by the DPJ administration and taken over by the Abe administration, was defined as a “halving target” for the fiscal deficit that was meant to reduce the FY2015 primary balance (PB) deficit (fiscal balance deficit calculated as the difference between primary balance expenditures and tax revenues and non-tax revenues) against the GDP to half by FY2010. This target was safely reached for the PB deficit combining national and regional governments, with the national government being one step away from improving the fiscal balance.

In this way, the Abe administration maintained a cautious stance toward expanding fiscal spending, and the considerable increase in tax revenues occurred through two consumption tax hikes and other measures. These moves contributed significantly to fiscal consolidation, whereas it hindered the policy objective of overcoming deflation. In the future, if someone were to talk about the Abe administration’s economic policy by looking only at the data without checking the developments over these 10 years, they might end up with the incorrect interpretation that Abenomics was a policy package for realizing a doubled consumption tax rate and advancing fiscal consolidation by supporting the economy through large-scale monetary easing.

The transition in unprecedented easing

The negative interest rate policy (NIRP), whose introduction was decided at the Monetary Policy Meeting of BoJ in January 2016, garnered avid interest partly because of the strangeness that “the person who borrows money receives interest from the person who lent the money.” However, in terms of a shift in the monetary policy framework, the “Yield Curve Control” (YCC) (quantitative and qualitative monetary easing with yield control), whose introduction was decided in September of the same year, was more significant. This is because it created a major change that allowed the monetary policy operational framework to manipulate funds from the monetary base to interest (interest on BoJ’s Current Account and 10-year JGB yields).

Until this policy change was implemented, BoJ was supposed to purchase government bonds so that the balance of its holdings of Japanese government bonds (JGBs) would increase at an annual pace of about 80 trillion yen. However, with the introduction of YCC, “about 80 trillion yen” came to be considered the “target” for the bank’s purchases, with the actual purchases (increase in JGBs) gradually decreased on this occasion. Under these circumstances, progress was made in “stealth tapering” (compression of asset purchases without clear announcement), and as of the end of March 2022, the pace of increase in the balance of BoJ JGBs slowed to about the same pace as in the end of March 2012, when the monetary policy was in operation under former Governor Shirakawa Masaaki (looking at the calendar years, the amount outstanding of JGBs held as of end of December 2021 was 14 trillion yen less than at the end of December 2020, the first decrease since 2013).

Recently, with the rise in long-term interest rates in the United States, there has been upward pressure on long-term interest rates in Japan as well, and the fluctuation range of long-term interest rates has increased by 0.25% and “unlimited” fixed-rate purchase operations (purchases of government bonds) are being implemented to keep it down. As a result, the amount of JGB purchases in June 2022 reached 16 trillion 203.8 billion yen, the largest monthly amount ever, but even then, the amount outstanding of JGBs held increased by merely 4 trillion 216.4 billion yen. This is due to the fact that the “bold monetary easing” under Governor Kuroda lasted more than nine years, so that the government bonds purchased at the start of the QQE now shall be redeemed in large quantities.

This means that, depending on the operation of financial policy, the time is coming when it will be possible to compress the BoJ balance sheet. For the time being, we are not in an environment that will significantly change the monetary policy framework, but adjustments toward an “exit” of financial policy are steadily progressing.

3. Interesting and eventually sad Abenomics

Now we look at another aspect of Abenomics and Kuroda’s “bazooka,” including political and social movements, and record the social conditions at that time.

The DPJ administration and the “super strong yen”

Ten years ago, in the summer of 2012, the exchange rate was hovering around 1 USD = 78 JPY. The “extremely strong yen” (an all-time high of 1 USD = 75.32 JPY was recorded on October 31, 2011) that arose in the wake of the Great East Japan earthquake in March of the previous year (2011) eventually returned toward a weak yen, but there was a widely shared recognition that an excessively strong yen hampers the economy. Exports declined significantly from summer to winter in 2012. Imports showed a downward trend due to the economic downturn, but trade balance deficits persisted nonetheless.

Under these circumstances, the economy peaked in March 2012 and entered a recessionary phase, while consumer prices fell compared to the same month in the previous year starting in May 2012. In June, the Tokyo stock exchange stock price index (TOPIX) hit its lowest level since the bubble economy burst, after which stock prices continued to stagnate.

Politically, the Ozawa Ichiro group left the party over the bill for consumption tax (July 2, 2012), thus dividing the DPJ. Under these circumstances, the DPJ continued to operate an unstable administration, with the special deficit-financing bond bill meant to compensate for the lack of financial resources in the FY2012 budget (deficit) finally making it through the Lower House at the end of the summer (August 28) (the ruling party had less than a majority in the Upper House, so there was no prospect of the bill being enacted). The Noda administration’s approval ratings continued to decline, with an opinion poll by the Asahi shimbun newspaper showing 18% in October, the lowest since the inauguration of the administration. Three years earlier [Lower House election 2009], many people happily picked up a manifesto with “Change of Government” written on the cover, but the course of the administration that followed led people to think of the word “manifesto” as signifying a dubious election leaflet.

In this way, Abenomics was born in a dreary atmosphere of having no future in terms of politics or the economy alike, so that “bold monetary easing” came to be perceived as symbolic of a big economic policy shift which would come through by a change of government. Although the sense of trust and anticipation for the LDP did not increase significantly, the distrust and anxiety about the DPJ administration outweighed it, so that the LDP’s return to power was supported by many people thinking along the lines of “I’ve had enough of the DPJ” and “I just want to get out of the current situation as soon as possible.”

After a party leaders’ debate in the Diet on November 14, 2012 and the dissolution of the House of Representatives on November 16, 2012, stock prices rose, and the yen depreciated somewhat against the US dollar. At the end of 2012, the Nikkei Stock Average exceeded 10,000 yen, and the exchange rate showed a weak yen at 1 USD = 85 JPY.

“Bold monetary easing” and “Kuroda’s bazooka”

At the beginning of 2013, there was much talk about the exchange rate being in the “Ishiba range” (1 USD = 85–90 JPY) and the “Hamada line” (1 USD = 95–100 JPY) (estimates said to have been given by Ishiba Shigeru, then LDP’s Secretary-General, and Hamada Koichi, Special Advisor to the Cabinet), and when the focus was on when exchange rate would reach these ranges (looking at what actually happened, the “Ishiba range” was reached in the middle of January 2013, while the “Hamada line” was reached in the middle of March 2013).

On January 22, 2013, the “Joint Statement” between the government and BoJ was released, and the outline for the realization of “bold monetary easing” was prepared. When Prime Minister Abe stated “deflation is a monetary phenomenon and thus can be overcome by monetary policy” at a meeting of the Lower House Budget Committee on February 7, that perfectly expressed the feelings of those who have high hopes for the role of monetary policy.

This answer was elicited by Maehara Seiji in the DPJ (at the time). In the fall of 2012, Maehara became Minister of State for Economic and Fiscal Policy and requested BoJ to implement powerful monetary easing. Minister Maehara attended the Monetary Policy Meeting on October 5, 2012, which was the first time a minister attended since the Minister of State for Economic and Fiscal Policy Takenaka Heizo did so in in April 2003, nine years prior.

On March 20, 2013, BoJ’s Governor and Deputy Governor were replaced (Governor Shirakawa stepped down on March 19 almost three weeks before his term was due), so that the Monetary Policy Meeting on April 4 was held under the new leadership of Governor Kuroda and Deputy Governors Iwata Kikuo and Nakaso Hiroshi, deciding on the introduction of QQE. A strong impression was made in TV news footage and newspaper photos when Governor Kuroda appeared at the press conference to explain the significance of “monetary easing of a different dimension” while pointing to a flip chart with “2%,” “2 years,” and “2 times” written in large letters in red letters.

This policy, dubbed “unprecedented easing” and “Kuroda’s bazooka,” was praised as a big financial policy shift by some, but there were also some who expressed concern about “hyperinflation.” However, looking back on the course of events that followed, the 2% price stability target that was “to be achieved as soon as possible, with a time horizon of about two years in mind,” remained unreached for nine years. As mentioned, the consumption tax rate hike in April 2014 helped slow the pace of rising prices through a drop in consumption.

Growing concerns about deflation and delays and further delays on the consumption tax hike

Following upon April 2014, the consumption tax rate was supposed to be raised again in October 2015, but the increase to 10% was postponed twice. This was because there were concerns that a consumption tax hike would put downward pressure on the economy, thus risking a return to deflation.

The first delay was announced in November 2014. The forecast for the consumption tax rate hike in April 2014 (from 5% to 8%) was that the negative impact would disappear in the summer and that the economy would return to growth, but consumption actually continued to stagnate (Fig. 1 above). Coupled with the effects of the fall in crude oil prices in the summer of the same year, the pace of rising prices slowed. In response to these weak developments in the economy and prices, additional monetary easing was implemented in October, and with an eye to avoiding a return to deflation, announcing the delay at this point matched the management of monetary policy.

After that, the economy showed signs of picking up slightly, but partly due to the effects of the slowdown in the Chinese economy, the economy followed a downward trend from the fall of 2015, and in 2016, CPI (yr/yr) became negative. In response to these weak developments in the economy and prices, BoJ decided to introduce NIRP at the Monetary Policy Meeting in January 2016 (implemented from the reserve maintenance period of February 2016). Against this background, a renewed delay of the consumption tax hike was announced in June 2016. This decision was also in line with BoJ’s policy response to avoid the risk of a return to deflation.

The illusion of the argument that “a consumption tax hike should not be used as a tool for political strife”

Since there may be different ways of thinking depending what emphasis is placed on fiscal consolidation and overcoming deflation, it is not strange that objections were raised against the delay and further delay of the consumption tax hike. This is because, given the perception that the risk of government bond markets becoming unstable is higher than the risk of a reversal to deflation, it would have been natural to implement the consumption tax hike as scheduled.

However, if you think about it calmly, it is very strange that some criticized the delayed consumption tax hike because “a consumption tax hike should not be used as a tool for political strife.” Looking back at the history of consumption tax hikes, the decision on whether to raise the consumption tax rate as scheduled on a certain date stipulated by law is to be made by the Cabinet at each point in time (item confirmed in the “three-party agreement” of the DPJ, the LDP, and the Komeito on Comprehensive Reform of Social Security and Tax), with Article 18, Paragraph 3 of the Supplementary Provisions to the Comprehensive Tax Reform Act, which determines that the consumption tax rate should be raised twice, states that “necessary measures, including suspended implementation, shall be taken after comprehensively taking into account economic conditions and other factors.”

Therefore, the decision to postpone the consumption tax hike was an act carried out under due process, as was the decision to implement it as scheduled, so there must not have been any need to check confidence in the delay through an election if there existed an environment for it to be accepted quietly. In this regard, among the pundits who complained that “a consumption tax hike should not be used as a tool for political strife,” there were at least a few who objected to the delays of consumption tax hike.

Of course, it is not strange to argue that the consumption tax hike should be carried out as scheduled by arguing that the economic environment does not preclude its implementation. It is necessary to closely examine whether the decision to postpone it was appropriate, and it is natural to explore the pros and cons of controversial policy issues, yet we must be careful about voicing criticism with the motivation that “a consumption tax hike should not be used as a tool for political strife.”

The Noda administration’s failure to verify the public’s confidence in an election before passing the bill for consumption tax at both Upper and Lower Houses very much led to the criticism that “the DPJ administration decided to renege on a promise made before the change of government and opted for a consumption tax hike.” This led to a slump in support for the DPJ and the political parties to which DPJ-related politicians belong. This makes even more sense when we take this into consideration.

In light of the above, pundits who criticized the decision to delay the consumption tax hike on the grounds that “a consumption tax hike should not be used as a tool for political strife” unfortunately showed themselves to either lack sufficient fundamental training to read basic information and legal texts about the processes of the Comprehensive Reform of Social Security and Tax, or expressed a biased opinion with the intention of making the delay a tool for political strife from a particular political standpoint.

What could be achieved and what could not be achieved

If we were to name big changes between now and 10 years ago, one of the first to come to mind is probably the way we look at economic conditions. “Deflationary recession” is a thing of the past, and “high prices” have become a major social problem. Of course, if we go back 10 years, meaning another four years from 2012, we will see that the same “high prices” due to rising energy and food prices were a big issue, just as we do now, but it is too early to judge whether the change taking place is structural or temporary. However, I believe there should be a certain consensus that we have “created a situation that is not deflation.”

However, this development is not accompanied by a sufficient increase in wages as rising prices cause real wages to decline and household consumption to go down. The depreciation of the yen did not bring about as much growth in exports as expected and was a factor in raising the cost of living through higher import prices. The increase in consumption tax rate contributed to improving fiscal balance through an increase in tax revenues, but it also caused the economy to stagnate through a drop in consumption.

As a result of this process, the “2%” price stability target was not achieved during the tenure of Prime Minister Abe, but the consumption tax rate doubled under a single cabinet (from 5% to 10%), significantly shrinking the fiscal deficit. Overall, the economic growth rate has remained low, but stock prices have risen considerably, and land prices have stopped declining. Of course, how to interpret these developments will yield different assessments depending on what position you assume.

Abenomics, which began amid hustle and bustle, came to a close with neither criticism for causing hyperinflation and a debt crash or praise for leading to economic expansion and achieving the price stability target. In April 2023, Governor Kuroda will leave BoJ and unprecedented easing will change form. Just like the Heisei boom and the “Bubble Economy” (the Japanese asset price bubble), Abenomics and Kuroda’s bazooka will eventually become a thing of the past and history.

Even so, memories of that time when macroeconomic policy garnered widespread public attention will never fade.

Translated from “Abenomics to Ijigen-kanwa—Dojidaishiteki kosatsu (Abenomics and Kuroda’s Bazooka: A Contemporary Historical Considerations),” SYNODOS. (Courtesy of SYNODOS. Inc.) [November 2022]

The original article appears at the SYNODOS site: https://synodos.jp/opinion/economy/28320/ (in Japanese)

Keywords

- Nakazato Toru

- Sophia University

- Abenomics

- monetary easing

- Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing

- QQE

- unprecedented easing

- Bank of Japan

- consumption tax hike

- rising prices

- CPI

- 2% price stability target

- fiscal policy

- Japanese Government Bonds

- weak yen

- exchange rate

- deflation

- public attention