How Does Political Regime Affect Economic Prosperity and Health?

“[…] democratization is associated with a decline in infant death in the long term, rather than the very short term.”

How do differences in political regime, such as between authoritarianism and democracy, affect a country’s economic prosperity and people’s health? I will use an econometric approach to political phenomena to address this question as I consider the reason why democracy should be defended.

Annaka Susumu, Assistant Professor, Hirosaki University

1. Political regime and economic affluence

Prof. Annaka Susumu

A political regime is defined as “the set of basic formal and informal rules that determine who influences the choice of leaders—including rules that identify the group from which leaders can be selected—and policies” (Geddes, Wright and Frantz 2014, p. 327).[1] It is a concept used to classify different political characteristics from country to country, such as democracy, authoritarianism, and autocratic regime.[2] How do differences in political regime affect economic affluence and people’s health? That is the question that this paper seeks to address.

Looking at North Korea and some African countries, one gets the impression that people live poor and unhealthy lives in countries classified as authoritarian rather than democratic. However, in China, which is also regarded as authoritarian, the economy is developing rapidly and the number of poor people is decreasing significantly. Moreover, there are many countries in the Middle East that have achieved economic affluence while being authoritarian. The lesson these examples suggest is that in order to discern the effects of different political regimes without bias, as many countries as possible must be included in the analysis.

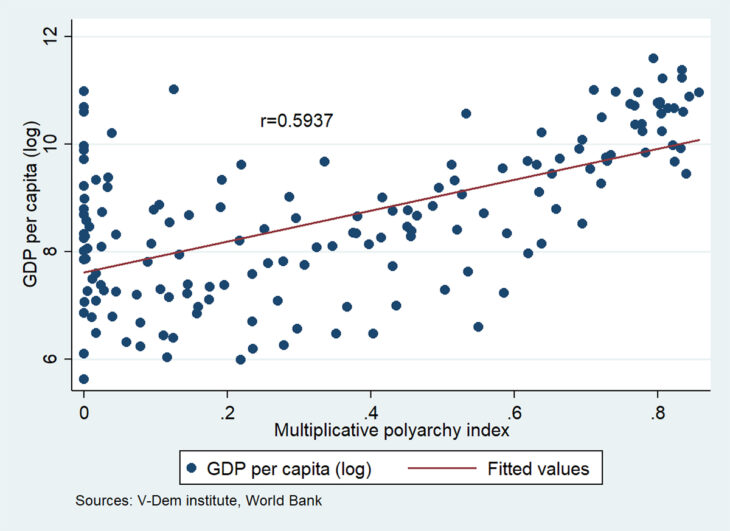

The relationship between political regime and affluence was first pointed out in empirical data by Lipset (1959). Confirming this with modern data gives us Figure. In this figure, the X (horizontal) axis shows the V-Dem Institute’s index (multiplicative polyarchy index; 0-1) for measuring degree of democracy and freedom, while the Y (vertical) axis shows the logarithm of GDP per capita (both include data from 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic). This indicates that the higher the degree of democracy, the higher the GDP per capita. However, there are many rich countries around the “0” degree of democracy. They are China and countries in the Middle East of China.

Figure: Relationship between degree of democracy and economic affluence

The assertion of Lipset (1959) that rich countries tend to democratize, later dubbed “Lipset’s theory,” was developed. However, this analysis only shows correlation, which makes it impossible to infer a causal relationship as Lipset claims. Even if we can confirm a relationship, meaning that there are many rich countries among those democratic, that correlation alone is not enough to determine whether rich countries have it easy to democratize or whether democratic countries have it easy to become rich. Moreover, even if there are hidden factors that facilitate democratization and economic growth, it is possible that there are no direct relationships between them, so this may be explained by a third factor. These problems are called endogeneity, but this paper focuses on the impact of political regime on affluence and health, so it is important to accurately capture the direction of cause and effect. To this end, the approach called “causal inference,” which has become popular in recent years, is of great significance. In general, experimental techniques of causal inference have been established in social science as well, with widespread applications. However, it is necessary to devise methodological ingenuity when it is impossible to conduct new experiments and analysis must be carried out based on existing observational data.

One example is analysis using so-called instrumental variables. I will leave the details to technical books and papers, but in a nutshell, it can be explained as follows. If we cannot only expect that an independent variable (political regime here) affects a dependent variable (in this case, economic affluence) but we also cannot exclude the possibility of reverse causality, then we seek a variable (the so-called instrumental variable) that has effects only through the independent variable without directly affecting the dependent variable. This is an analytical method that attempts to address the endogeneity problem, including the direction of causal relationship, by analyzing the relationship between this variable and the independent variable and finding its relationship with the dependent variable.

A particularly influential study using this method is Acemoglu et al. (2019), which analyzes data from 1960 to 2010. The instrumental variable used by Acemoglu et al. in this study is the degree of democratization of neighboring countries. If neighboring countries change their regime to democratic, that will promote democratization in the country studied, and conversely, if neighboring countries change from democratic to authoritarian regimes, democratization in the country studied will regress. However, the degree of democratization of neighboring countries is unlikely to have a direct impact on the economic growth of the country studied. It is assumed that economic growth will only be indirectly affected through the impact on democratization in that country. The results of the analysis, which were obtained after carefully anticipating influence relations in this way, confirmed the causal direction that democracy promotes economic growth. Acemoglu, one of the world’s leading economists with the most citations in economics over the past decade, is at the center of this debate.

More recently, Marx, Pons, and Rollet (2022) use a causal inference technique called regression discontinuity design (RDD) to analyze the impact of regime change by elections which play an important role in a democracy in economic growth. This analysis shows that when comparing narrow victories and narrow defeats of opposition parties in elections, the results are considered to be almost random, thus making an experimental comparison of opposition party victories and defeats possible. Therefore, we can extract the pure causal effect of regime change that takes into account various influences. The results of this analysis show that regime change has a positive effect on economic performance, including economic growth, inflation rate, and unemployment rate.

In this way, democratic nations are said to have the effect of improving economic conditions by supporting frequent regime changes. Additionally, it has been pointed out that while inequality is one economic problem that is not easily overcome in democratic nations, democratic nations still reduce inequality more than authoritarian regimes do (Wong 2021).

2. Political regime and health

Next, let us look at the relationship between political regime and health. Skepticism about democracy is said to be on the rise in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. China and other authoritarian regimes are said to have succeeded in containing the pandemic by restricting people’s freedoms more quickly than democratic nations. This situation runs counter to the affluence narrative discussed above. It has been argued that authoritarian regimes have the upper hand over democratic nations. Japanese media, including TV and newspapers, have presented research by Narita and Sudo (2021), which analyzes these claims based on data in a sophisticated way. They argue that democratic nations have had statistically significantly more deaths from COVID-19 and lower economic growth during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In reality, however, the data reported by countries vary in reliability. Specifically, authoritarian regimes have tended to be reluctant to report domestic data, especially economic data, and it has been pointed out that their data may be less transparent and more unreliable (Hollyer, Rosendorff, and Vreeland 2011: Martinez 2021). This is probably also true for data related to COVID-19. Annaka (2021 [Political Regime, Data Transparency, and COVID-19 Death Cases]) and Annaka (2021), which introduced this in Japanese, argue that while authoritarian regimes appear to have the upper hand when simply analyzing data reported by the countries, democratic nations are not inferior when re-analyzing the data with transparency in mind.[3]

There are other examples of analysis that take into account these data issues by other methods. For example, the WHO refers to data called excess mortality as the “true death toll” of the COVID-19 pandemic, thought to result from more reliable data collection than with the data reported by countries as COVID-19 deaths. Excess mortality is defined as “the difference in the total number of deaths in a crisis compared to those expected under normal conditions. COVID-19 excess mortality accounts for both the total number of deaths directly attributed to the virus as well as the indirect impact, such as disruption to essential health services or travel disruptions.”[4] Using this data instead of the figures reported by countries as COVID-19 deaths, it was reported that the excess mortality of democratic nations was statistically significantly lower, rather than authoritarian regimes taking the lead (Jain, Clarke, and Beaney 2022). Thus, although there was a view that authoritarian regimes had the upper hand in COVID-19 countermeasures in the early days of the pandemic, the tide appears to be turning more recently.

The findings of studies analyzing the relationship between political regime and COVID-19 to date can be summarized in this way, but of course, the problem is not yet over. It has only been a few years since the outbreak of COVID-19. As such, I would now like to consider the relationship between political regime and health issues from a long-term perspective.

McMann and Tisch (2021) analyse the impact of political regime on a variety of types of infections over a long period of time from 1900 to 2019. According to their study, the number of deaths from infections in democratic nations tends to be lower than in authoritarian regimes. What is more interesting about their study is that while certain elements of democracy, such as fair elections and legislative and judicial constraints, are associated with fewer deaths, other elements like increased suffrage itself or freedom of expression are not correlated with deaths. These correlations suggest that the process of replacing an incumbent that that does not take into account the health needs of the people may also help protect the people from infections. This is consistent with the work of Marx, Pons, and Rollet (2022) mentioned above. COVID-19 is not the only infection that has plagued humanity, but as the study points out, results reported so far have been in favor of democracy from a long-term perspective.

Aside from infections, it is known that democracy also has the upper hand with health in general. Annaka and Higashijima (2021), Gerring et al. (2021) use long-term data from 1800 or 1900 to recent years to analyze the relationship between political regime and infant mortality, which is considered a particularly useful health-related indicator for understanding people’s living conditions. In analysing these issues, it is necessary to take into account the general tendency of democratic nations to be rich, as described above. This is because, rather than differences in political regime explaining infant mortality rate, whether the population is rich or poor has a significant impact on infant mortality rate. Even when taking such relationships into account, these studies find that democratic nations and experiences of democratization are linked to lower infant mortality rates as well as that the direction of the influence is that democracy and democratization are what is affecting infant mortality rates, rather than the opposite. In light of these issues, Annaka and Higashijima (2021), like Acemoglu et al. (2019), use instrumental variables that take advantage of democratization and democratization waves in neighboring countries, paying attention to causal relationships and reporting that democratization is associated with a decline in infant mortality in the long term, rather than the very short term.

Finally, I would like to touch on research called metanalysis. This is research that compares multiple previous studies together and verifies how strongly certain claims are presented, eliminating bias as much as possible. Gerring, Knutsen, and Berge (2022) analyze more than 600 papers and find that results showing that democracy dominates in many areas are robust. Even when taking into account the possible bias that democracy is desirable, they conclude that democracy has a statistically significant desirable impact on human rights, people’s health, and so forth. On the other hand, for some specific economic problems, such as social benefits and inflation, the study did not necessarily confirm that democracy is better.[5]

3. Democracy as a means to avoid the worst

Democracy is not perfect. It is by no means a superior system that produces outstanding leaders. At the same time, however, it is difficult for it to create leaders who cause extreme tragedy. This is a vital function of democracy. Let me give you some specific examples that went down in history. Look at the pasts of Russia and China, which still remain prime cases of authoritarianism. These countries have experienced great famines in the past, sometimes called “manmade.” They were the results of the authoritarian leaders Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong prioritizing the state’s appearance and privileges, killing many citizens (Brown 2012; Dikötter 2019). Those consequences of policy, as Amartya Sen has pointed out specifically for China, emerged from intrinsic flaws in the authoritarian system itself (Sen 2017). There are numerous other tragic histories of authoritarian regimes, such as Cambodia and North Korea. It is conceivable that there are some relatively better states, such as Cuba or Vietnam, but it is equally true that there are democratic countries that do not work so well. Nevertheless, failure in an authoritarian regime can lead to tragedies that are incomparable to what failure in a democratic nation can cause. Donald Trump behaved autocratically and the United States was plunged into political turmoil, but his administration did not persist through regime change. In this way, misgovernment (if one calls it so) is ousted. That is a rule of democracy. Karl Popper wrote, “Any prudent theory about a free society’s political regime ought not start with the question ‘who should rule?’ but rather ‘how can we design our political system so that rulers who are unwise or evil do not have too much power and do not cause too much damage?’” In this way, he defended democracy as it ensures this function (Popper 2014, p. 203).

A political regime that is good in good times but thoroughly bad in bad times does not improve people’s lives as a result. This is why democracy, a system that avoids the worst even if it does not achieve the best, should be defended.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the useful comments of Kohno Masaru, Higashijima Masaaki, Kita Munenori, Yajima Naonari, Kitagawa Ritsu.

References

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P. and Robinson, J.A. (2019) “Democracy Does Cause Growth,” Journal of Political Economy, 127 (1): 47-100.

Annaka, S. (2021) “Korona-ka ni okeru Seijitaisei no Jisshobunseki: Minshushugi wa Kenishugi ni otorunoka?” (An Empirical Analysis of Political Regimes in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Is democracy inferior to authoritarianism?), Chuokoron, 74-81.

Annaka, S. (2021) “Political Regime, Data Transparency, and COVID-19 Death Cases,” SSM – Population Health, 15, 100832.

Annaka, S. and Higashijima, M. (2021) “Political Liberalization and Human Development: Dynamic Effects of Political Regime Change on Infant Mortality across Three Centuries (1800–2015),” World Development, 147,105614.

Brown, A. (2012) “The Rise & Fall of Communism,” Bodley Head

Colagrossi, M., Rossignoli, D. and Maggioni, M. A. (2020) “Does Democracy Cause Growth? A Meta-analysis (of 2000 Regressions),” European Journal of Political Economy, 61, 101824.

Dik¨otter, Frank (2019) “Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe,” 1958–62, Walker & Company

Frantz, Erica (2021) “Authoritarianism—What Everyone Needs to Know,” Oxford University Press

Geddes, B., Wright, J. and Frantz, E. (2014) “Autocratic Breakdown and Regime Transitions: A New Data Set,” Perspectives on Politics, 12 (2): 313-331.

Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H. and Berge, J. (2022) “Does Democracy Matter?” Annual Review of Political Science, 25: 357-375.

Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Maguire, M., Skaaning, S-E, Teorell, J. and Coppedge, M. (2021) “Democracy and Human Development: Issues of Conceptualization and Measurement,” Democratization, 28 (2): 308-332.

Hollyer, J. R., Rosendorff, B. P. and Vreeland, J. R. (2011) “Democracy and Transparency,” Journal of Politics, 73 (4): 1191-1205.

Jain, V., Clarke, J. and Beaney, T. (2022) “Association between Democratic Governance and Excess Mortality during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Observational Study,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, Online First.

Lipset, S. M. (1959) “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy,” American Political Science Review, 53 (1): 69–105.

Martinez, L. R. (2021) “How Much Should We Trust the Dictator’s GDP Growth Estimates?” University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper, No. 2021-78.

Marx, B., Pons, V. and Rollet, V. (2022) “Electoral Turnovers,” NBER Working Paper, No. 29766.

McMann, K. M. and Tisch, D. (2021) “Democratic Regimes and Epidemic Deaths,” V-Dern Institute Working Paper, SERIES 2021: 126.

Narita, Y. (2022) “22 Seiki no Minshushugi—Senkyo wa Arugorizumu ni nari, Seijika wa Neko ni naru” (Democracy in the 22nd Century: Elections become algorithms, politicians become cats), SB Shinsho

Narita, Y. and Sudo, A. (2021) “Curse of Democracy: Evidence from 2020,” Cowles Foundation Discussion – Papers, 2281.

Popper, K. (2014) “After The Open Society—Selected Social and Political Writings,” Routledge

Sen, A. (2017) “Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation,” Oxford University Press

Wong, M. Y. H. (2021) “Democracy, Hybrid Regimes, and Inequality: The Divergent Effects of Contestation and Inclusiveness,” World Development, 146, 105606.

Translated from “Seiji-taisei wa Yutakasa ya Kenko ni donoyona Eikyo wo oyobosunoka?” (How do political systems affect wealth and health?),” The Keizai Seminar, October/November 2022, pp. 29-34 (Courtesy of Nippon Hyoron sha Co., Ltd.) [December 2022]

Keywords

- Annaka Susumu

- Hirosaki University

- political regime

- authoritarianism

- democracy

- degree of democracy

- politics

- economy

- health

- econometric approach

- economic affluence

- leaders

- regime change

- endogeneity

- causal inference

- instrumental variables

- Daron Acemoglu

- Seymour M. Lipset

- Lipset’s theory

- regression discontinuity design

- COVID-19

- true death toll

- excess mortality

- infant mortality

- metanalysis

- Karl Popper