Monetary Policy after the Removal of Negative Interest Rates: Emphasis on “continuation of easing” and concerns about yen depreciation

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has almost completely ended large-scale monetary easing. The BoJ has stated that accommodative financial conditions will be maintained for the time being. The Bank has taken an important step back to “normal monetary policy,” but the journey has just begun.

Key Points:

- Clear message that there is no rush to raise interest rates

- Remaining high import prices due to the weak yen are a turbulent factor

- Focus on revisions to future guidance and JGB (Japanese Government Bond) purchases

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has almost completely ended large-scale monetary easing, including its negative interest rate policy, and taken a step toward financial normalization. The BoJ will end its control of long-term interest rates and return to traditional policy management using short-term interest rates as its sole policy tool, and will gradually end its purchases of risky assets. Meanwhile, the Bank has continued to purchase long-term government bonds and has stated that accommodative financial conditions will be maintained for the time being. I would like to reflect on the key points of the policy changes, the outlook for future policy, and related issues.

The BoJ abolished the “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE) with a Negative Interest Rate” framework, which had been in place since 2016. Only short-term interest rates will be the main policy tool, and the policy rate will be raised to 0-0.1%. In terms of risk assets, new purchases of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and real estate investment trusts (REITs) will end immediately. The inflation-overshooting commitment to expanding the monetary base (money supply) going forward has also ended. Previously, the Bank had sought to increase policy effectiveness by committing to “expand the monetary base until the year-on-year rate of increase in the observed consumer price index (CPI) [CPI inflation rate] exceeds 2 percent and remains above that level in a stable manner.” Consumer price inflation has been above 2 percent for the past two years, but it is debatable whether it is “stable” because it is mainly due to cost pressures from rising energy and commodity prices. However, the BoJ seems to have prioritized the end of large-scale monetary easing and determined that the conditions have been met.

In addition, measures that have been considered for the transition from large-scale monetary easing have been added. First, the Bank will continue to purchase long-term government bonds at the same level as before (about 6 trillion yen) and will conduct flexible fixed-rate purchase operations in response to a sharp rise in long-term interest rates. As a result, the amount outstanding of the BoJ’s JGBs is expected to remain about the same. This will put downward pressure on long-term interest rates, both from the effect of the flow of JGB purchases and the effect of the stock of JGB holdings. Furthermore, as a guideline for its future policy stance, it stated that “accommodative financial conditions will be maintained for the time being” based on the current outlook for economic prices. This is interpreted as a state in which the policy rate can be kept low relative to a neutral interest rate level that neither heats nor cools the economy. This seems to be a message from the BoJ that it is in no hurry to raise interest rates.

The BoJ decided to fully unwind the large-scale monetary easing, while taking into account transitional measures, based on the belief that the 2% CPI inflation rate, which is the policy target, can be expected to be achieved in a stable and sustainable manner. In fact, full responses to the spring labor-management negotiations were received one after another, and the wage increase rate (first round) announced by Rengo (Japan Trade Union Confederation) reached a national average of over 5%, even higher than in 2020, and over 4% for small and medium-sized enterprises. Some estimates suggest that the base increase will exceed 3%. The decision seems to have been supported by confirmation of a strengthening of the virtuous cycle between wages and prices, combined with information from interviews.

Despite the major policy change, the market reaction was generally smooth. Long before the policy change, the BoJ had indicated the content of the policy change through an unprecedented dissemination of information. On February 8, Deputy Governor Uchida Shinichi announced regarding policy management after the termination of negative interest rates, “[…] it is hard to imagine a path in which it would then keep raising the interest rate rapidly. [The Bank would,] I think, maintain accommodative financial conditions […].” Regarding the purchase of government bonds, he said, “[…] it will take careful measures so as not to create discontinuity [before and after the revision], and will make sure that the amount of JGB purchases will not change significantly and interest rates will not rise rapidly.”

In fact, it was announced that the accommodative financial environment will continue and that the BoJ will continue to purchase long-term government bonds at the same scale as before. It is unusual for the content of the policy change to be so specifically hinted at in advance. A sudden rise in long-term interest rates, as the BoJ had hoped, was avoided. What is remarkable about the market reaction after the policy change is that even though the large-scale monetary easing was almost completely removed and interest rates were raised, the exchange rate reacted and the yen depreciated. This seems to be due to the fact that the BoJ’s statement on maintaining an accommodative financial environment made it clear that the interest rate differential between Japan and the United States would remain high for some time, as inflationary pressures in the United States have been stronger than expected and long-term interest rates in the United States have been rising.

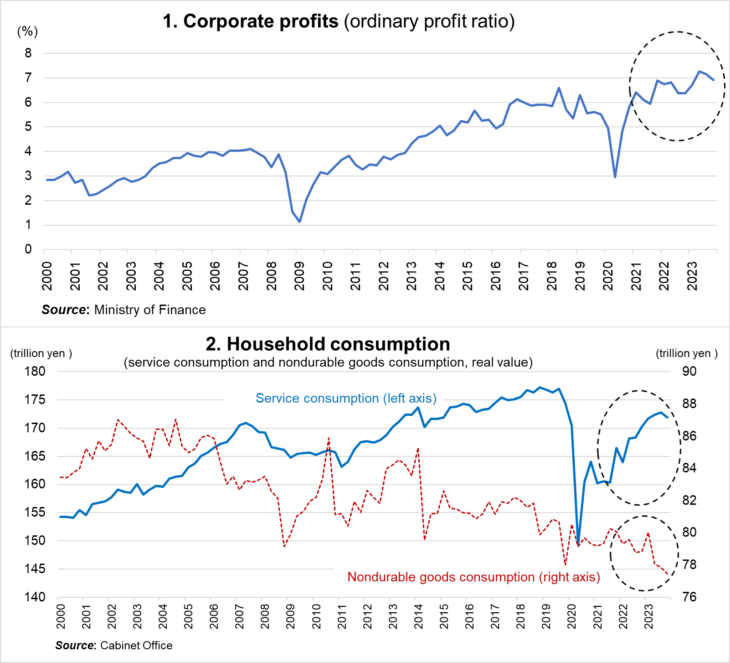

What will be the pace of further interest rate hikes in the future? Future movements in the policy rate will depend on the outlook for price developments in the economy. Overall, the corporate sector is doing well, but the household sector is cautious and the strength of domestic demand is currently in question. First, in the corporate sector, there has been a noticeable improvement in corporate profits. The ordinary profit ratio fell sharply as a result of the coronavirus shock, but it has continued to improve steadily since then and remains significantly higher than before the coronavirus pandemic (see Figure 1).

On the other hand, households are spending cautiously. Overall consumer spending has barely recovered to pre-pandemic levels and is currently weak. Consumption of services, which fell as a result of the consumption tax hike and the coronavirus shock, has not yet recovered to pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 2). Consumption of nondurable goods, which includes spending on daily necessities and food, is also declining. The recovery in domestic demand is lacking in strength, and if the future recovery is expected to be gradual, there is little discomfort in the outlook that there will be no rush to raise interest rates. Of course, if wages continue to rise on the back of strong corporate profits, the outlook for permanent household income will improve and the recovery in consumption may gain momentum. If demand for services becomes strong, it will be easier to pass on cost increases from wage increases to prices, and the “wage increases → price increases” channel will become stronger. In this case, there would be an upside scenario in which the cyclical mechanism of prices and wages would become more robust, and interest rates would rise in a desirable manner.

If “slow rate hikes” becomes the current main scenario and this policy outlook becomes widespread, other issues will emerge. This is due to the above-mentioned exchange rate developments. The yen’s depreciation trend continues even after the yen weakened immediately after the policy change. Overemphasizing the guidance that the accommodative financial environment will continue may reinforce expectations that the widening interest rate differential between Japan and the United States will become more stable and last longer. If the risk of a strong yen is judged to be low, the carry trade, in which low-cost yen borrowing is invested in high-return dollar assets, will increase, and the force of the yen’s depreciation will continue to work. While the yen’s depreciation trend is positive for the profits of companies operating overseas, it may keep import prices high and weigh on household consumption. A slowdown in domestic demand is a factor in downward price movements, but when import prices rise, it becomes a factor in upward price movements due to cost pressures. Focusing on the latter factor alone has given rise to speculation about an earlier interest rate hike, and this is beginning to have a complex impact on expectations for the evolution of economic activity and prices as well as for the policy interest rate.

An accommodative policy stance and continued purchases of long-term government bonds are seen as playing an important role in containing shocks to the economy. On the other hand, it has become clear that such efforts can have unexpected and complex effects. Going forward, the question will be how to maintain or revise future guidelines and measures for the purchase of government bonds. Navigating the current transition period from large-scale monetary easing is not easy. The BoJ has taken an important step back to “normal monetary policy,” but the journey has just begun.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 9 April 2024 under the title, “Mainasu-kinri Kaijo-go no Kinyuseeisaku (II): ‘Kanwa-keizoku’ kyocho, enyasu no kenen mo (Monetary Policy after the Removal of Negative Interest rates (II): Emphasis on ‘continuation of easing’ and concerns about yen depreciation),” The Nikkei, 9 April 2024. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Miyao Ryuzo

- Kobe University

- Bank of Japan

- monetary policy

- Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing

- QQE

- large-scale monetary easing

- interest rates

- negative interest rates

- monetary easing

- yen depreciation

- weak yen

- import prices

- JGB

- Japanese Government Bond

- long-term government bonds

- financial normalization

- normal monetary policy

- monetary base

- money supply

- consumer price index

- household spending

- corporate profits

- wages

- domestic demand