Arts and Entertainment Workers Appeal

The filming of a reality-seeking movie can sometimes be a dangerous experience. Still, they put their pride as actors and stuntmen on the line for a single scene. But there are cases of death and injury…

Photo: Graphs / PIXTA

Are arts and entertainment workers freelance? The answer is yes and no.

If people who work like craftsmen in a long-established industry, such as the entertainment industry, were suddenly told, “You are a freelancer,” they would probably feel uncomfortable. The same would probably be true for sole proprietors in agriculture, forestry and construction, seafarers, and people in the transportation industry, such as private taxi drivers and Akabou.[1] After all, traditional self-employment is not a new way of working.

In the first place, isn’t it too broad a range of industries to define freelance in one word? It would be more natural to think of it as just one part of the diverse ways of working. In fact, it has been studied under various names, such as employee-like and employment-like work styles.

In 2020, the Agency for Cultural Affairs (ACA) surveyed people working in culture and the arts and found that 94.6% of the 17,000 people surveyed were freelancers.

It is commonly believed that popular entertainers are employees or that those who work in entertainment production are company employees, but this is unfounded and untrue. Some stuntmen and staff who do dangerous work are employees, but not the majority.

Three years have passed since the beginning of the protection under the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance

Because they are not employed by a company, the workmen’s compensation insurance has not been applied to entertainment workers. Some people may still not know that it was first applied three years ago in 2021. It was a thorny road to reform the system. When the Cabinet Office (CAO) began to promote the protection of freelancers in its policies, the author asked the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) to investigate the actual situation of accidents involving entertainment workers and to apply insurance. The survey showed that about 60 to 70 percent of the accidents occurred during work and commuting. In the 57 years since 1963, I have identified 54 serious accidents resulting in death or injury.

Among these, 25 people died in accidents, including an actor who was directly hit by an explosive while filming a war movie in the mountains and had both of his legs blown off; two actors in another movie who went missing and drowned while filming a scene in which they were handcuffed together and crossing a river; an electric shock accident during underwater filming; a stage actor and lighting crew member who fell when suspended several dozen meters above the ground during filming; and an actor who developed pleural mesothelioma due to asbestos left in the theater.

As a result, the need for industrial accident compensation insurance was recognized and arts and entertainment freelance workers were protected in the same way as employees.

In response to this change in the system (Amendment to the Enforcement Regulations of the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act, 2021), we created a “special enrollment organization” to serve as a window for entertainment workers to apply for insurance in 2021. This is an organization made up of people involved in the relevant industry, and if it meets requirements such as setting its own accident prevention regulations and taking voluntary safety measures, it is possible to be approved by the MHLW or local Labor Bureaus.

“Nationwide Centre of Arts Workers’ Accident Compensation Insurance,” which we established, was approved on the day the system reforms were enacted, and in the three and a half years since, it has been supporting its members by providing training and setting up consultation desks staffed by occupational health physicians or clinical psychologists.

Those who have learned about this new system and felt the need for counseling pay their own insurance premiums and join. Looking at this situation, we can see that many people respect and protect their work as a job that supports culture and continues to improve itself. They seem to understand that protecting themselves is the professional way to work. This may be hard to believe for those whose companies pay their insurance premiums. I feel the pride and hard work of the people who make a living in the entertainment industry, and I have nothing but respect for them.

It should also be noted that there are an increasing number of cases where the insurance premiums are paid by the organizations to which the subscribers belong or by the client companies. There is no act that requires members to pay insurance premiums. Therefore, we recommend that they negotiate who will pay them.

The ACA’s “Guidelines for the Establishment of Appropriate Contractual Relationships in the Cultural and Arts Sector” also states that when entering into a contract, the parties should negotiate who will pay the insurance premium. It is wonderful to see mutual understanding being reached to create a safe and secure working environment.

Safety, health and health management

In the few years since the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act was revised (in 2021), the government has issued numerous guidelines and notices regarding the safety of self-employed workers in the entertainment industry.

For example, in 2021, a notice entitled “Regarding thorough measures to prevent occupational accidents among arts and entertainment workers” was jointly issued by not only the MHLW, but also the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC), the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), and the ACA. It states that it was prompted by the need for safety and health measures, as a survey conducted by the CAO found that about 20% of freelancers had suffered work-related accidents. It was noteworthy that “people working as freelancers, not employees” were included as targets of accident prevention measures.

Three years later, in 2024, the “Guidelines for Health Management of Self-Employed Workers” were formulated and published.

The main topics included: (1) raising awareness about health management, (2) understanding the risks of health problems due to dangerous and hazardous work, (3) health management through regular health check-ups, (4) preventing health problems due to long working hours, (5) preventing mental health problems, (6) preventing back pain, (7) managing occupational hygiene when working with information technology equipment, and (8) ensuring an appropriate working environment.

Since only 35.5% of arts and entertainment workers receive an annual health assessment, this is considered a necessary and important measure for healthy and safe work. The guidelines use the example of filming on set and recommend that people who cannot freely control their workload or working hours should consider the health problems caused by long working hours.

This is an eye-opening change for those in an industry used to being told that health and safety is a case of, “It is what it is — you are responsible for your own injuries and lunch.”

The reality of suicide from overwork

As the government’s efforts progressed, reports of the abuse of underage talent at the former Johnny & Associates, Inc. and the suicide of a member of the Takarazuka Revue Company were reported daily, and the Labor Standards Inspection Office issued a recommendation for correction. The reality of harassment and overwork, previously hidden in the entertainment industry, has become clear to everyone.

The suicide of the author of a TV drama series in January 2024 is still fresh in our minds. If the investigation report of the parties concerned is true, it would be considered a suicide due to overwork, and there is a suspicion that the right of attribution of the script she wrote was not exercised.

Suicide caused by excessive strain on the mind and body, such as stress and long working hours, is called “suicide by overwork.” This is also one of the industrial accidents.

It was not the responsibility of the client company to take measures such as stress checks for freelancers, measures to protect mental health in the workplace, or measures to prevent overwork. However, just because it is not an obligation, such incidents should not happen. Seven months after the incident, in August 2024, the government established the “Outline for Measures to Prevent Death and Injury from Overwork” as a priority measure to prevent death from overwork in the arts and entertainment sectors.

The reality of harassment victims

One of the biggest problems troubling those in this industry is harassment.

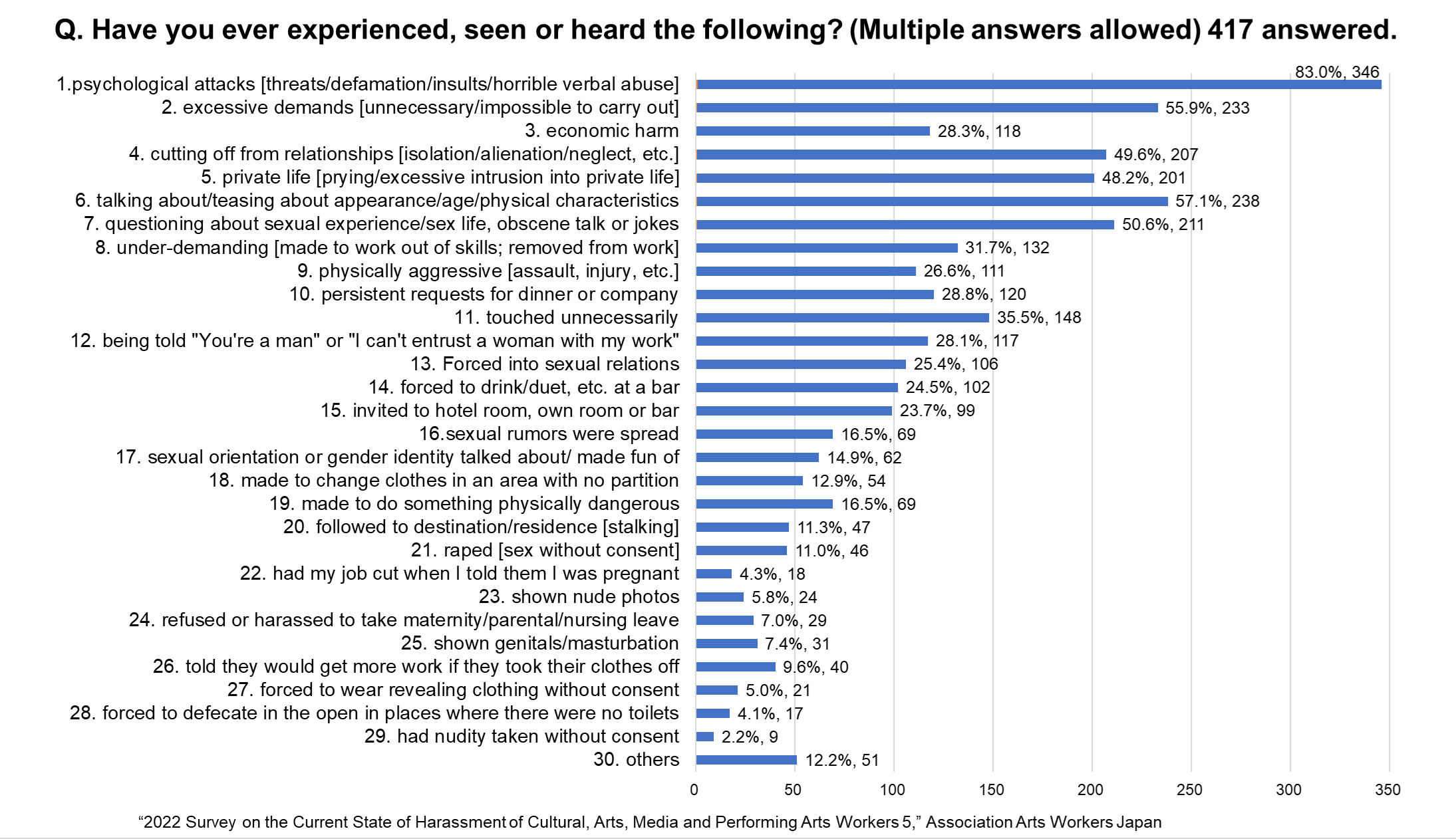

According to the 2022 survey, 93.2% of the 411 respondents had heard about, witnessed or experienced power harassment and 73.5% had heard about, witnessed or experienced sexual harassment. Detailed examples of victimization include “psychological attacks [threats/defamation/insults/horrible verbal abuse]” (83%), “told they would get more work if they took their clothes off” (9.6%), and “raped [sex without consent]” (11%), and there are many results that raise the question of whether they may be criminal (see figure: “Q. Have you ever experienced, seen or heard the following” [Survey on the Current State of Harassment of Cultural, Arts, Media and Performing Entertainment Workers]).

The reality has emerged in just a few years

It’s historic that the truth has come to light in an industry where people were too afraid to even answer surveys, let alone “the nail that sticks out gets hammered in.”

In 2024, a film director was arrested on suspicion of constructive forcible sexual intercourse. This was likely the result of one victim’s courage in coming forward.

There are also other suits underway involving actors alleging harassment by directors. The measures to prevent power harassment that were made mandatory for companies in 2020 did not apply to freelancers, but I feel that the power of these individuals has moved the entire industry everywhere.

Article 14 of the Act on Ensuring Proper Transactions Involving Specified Entrusted Business Operators (Freelance Act), which took effect in November 2024, requires specified entrusted business operators to take measures to prevent harassment.

Although this has finally been realized, it cannot be denied that the delay in legal development due to the fact that they are freelancers has delayed relief for many people.

Meanwhile, there are many examples of public-private partnerships in other countries, such as France’s Collectif 50/50 (50/50 collective) and the National Human Rights Commission of Korea and its affiliated Deun-Deun (Center for Gender Equality in Korean Film), both of which are run with government capital.

The Code of Conduct to Deal with Sexual Harassment, created by the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists (ACTRA), is a code of conduct aimed primarily at producers and directors. The “intimacy coordinator” system, which has spread from the United States to Europe, is a system that addresses sensitive scenes within this code. It is very effective because it allows contractors and the client to work together.

The role of the Freelance Act in the arts and entertainment industry

There are different opinions on the evaluation of the Freelance Act, but the concept of a contract has been created in a place where parties have long had to conduct transactions without any rules, and this will be an effective means of protecting themselves.

The act does not directly define freelancers, but refers to those who work on behalf of clients as “specified entrusted business operators (freelancers).” According to a 2020 CAO survey, there are 4.62 million freelancers, about 60% of whom are self-employed, and the purpose of this act is to eliminate the disparity in bargaining power when accepting work.

In addition, many people in the entertainment industry set up companies without employees, such as a one-person company or a company consisting only of living relatives, but are treated as freelancers under the Freelance Act. Therefore, there may be more people covered by this act than you would expect.

On the other hand, there are people who are not covered by this act. There are cases of farmers and artists who work without a direct contract with the client. However, problems have arisen even in the transactions of these people. For example, there have been cases where an artist created a work of art at the request of a museum and the museum lost it, or an artist died of carbon monoxide poisoning in an accident while creating the work, so further consideration is needed.

The reality of the contractual situation, which is always a cause for concern

As mentioned above, no matter how famous entertainment workers are, they are unlikely to be employed by entertainment agencies unless they also work as office staff, and in reality most are self-employed. For example, actors and entertainers are self-employed and sign management contracts with entertainment agencies, but according to a survey by the ACA, only 12.7% of them had signed service contracts. It may seem like a dream-shattering story, but that is the reality.

There is a lot of concern among parties about contracts, and when we asked what you would like to talk to a helpline about, the most common answer was contract issues.

Some of the problems that people have reported with contracts include, “The company won’t put the contract in writing,” “There’s no standard for compensation,” “The unit price hasn’t changed at all for many years,” “It’s taken for granted that you have to pay for your own insurance and other expenses,” “They use the fact that I’m a freelancer as an excuse, clients can make me work as much as they want,” “I feel like I’m not seen as a worker,” “It took three years to write a book, but I was only paid 40,000 yen and no copyright fees,” and “When I asked for a contract, I was told there had never been a case like this before.” It seems that the problems have been building up for many years.

It is said that generative AI learns from works without the permission of the copyright holder. Therefore, in the “AI Literacy of All Kinds of Creators Survey,” most creators are worried about the harm of AI, such as infringement of rights (93.8% of 26,831 respondents answered “Yes” to the question “Are you worried about infringement of rights and other harmful effects of AI?”). The government claims to protect creators, but only 2.6% of people actually sign a contract when they appear in music or video works on the Internet.[2] This means that even if we wanted to protect them, there is no way to do so.

The structure of undermining professional fulfillment

The MHLW’s “2023 White Paper on Measures to Prevent Karoshi, etc.,” which was approved by the Cabinet in 2023, is the first labor and social survey to target professionals in the arts and entertainment performers.[3]

More than half of the 640 people surveyed in the white paper had a household income of less than 4 million yen. In terms of household realities, about half were single-person households and the majority were unmarried households.

Excluding voluntary practice and equipment maintenance, only about 30% of people have two days off per week. However, since they may work part-time on their days off to earn a living, it is likely that they work long hours when their working hours are added up.

Despite such a hard life, their subjective well-being scores are extraordinarily high, with 80% scoring 6 or higher out of 10.

It is not hard to imagine that carriers of arts and entertainment professionals tend to value spiritual fulfillment and metaphysical values more than monetary success. These results suggest that their professional fulfillment is highly vulnerable to exploitation.

On the other hand, their mental health is extremely poor, with 52.1% suspected of suffering from depression or anxiety disorders. The causes of anxiety are often unexpected from the glamorous appearance on the surface, such as “I was told something hurtful at work” (48.5% in their 40s and 50s), “I was worried about whether I would get another job” (57.1%), “Industry customs mean I can’t say what I want to say freely” (32.7%), “I worry about results such as ratings, ticket quotas, and attendance” (37.7% or younger), “Industry customs mean I can’t say what I want to say” (38.1% in their 40s–50s), “My colleagues suddenly stopped coming to work” (28.5% or younger), and “A colleague or friend committed suicide” (10.0% in their 40s–50s).

People who experience such psychologically stressful events are more likely to have mental health problems later in life.

Degree of freedom/discretion in work style is in a gray area

Freelancers are supposed to work at their own discretion. In other words, they have the right to decide how to work without being directed or ordered by a company or corporation. However, actors, whose job is to act based on casting and directing instructions from producers and directors, are by no means free in all aspects.

The survey for the white paper includes questions based on the MHLW’s criteria for determining whether a person is a worker or not. (1) You can decide for yourself whether or not to accept work; (2) You can decide for yourself when to enter and leave the dressing room, studio, production site, etc., and when to take a break; (3) You can, at your own discretion, have someone else replace you when you take on a job; (4) You can hire assistants (dedicated staff, assistants, stuntmen, etc.) or increase the number of people as needed; (5) You have an office and accept work as part of the office; (6) You report income from performance work as business income or miscellaneous income on your own tax return; (7) You cannot decide whether or not to accept work; (8) You have been instructed by the person requesting the work not to accept work from other companies or entertainment agencies.

In response to these questions, the most common percentage of people who decide the method of work and compensation at their own discretion was “50%.” In other words, it can be said that this is a way of working that is not free at all and is in a gray area, so to speak.

This is probably the reason why people feel uncomfortable being called freelancers.

The lack of rules for many years has led to problems

As I have described so far, the reality of the entertainment industry is probably not a humane or decent way to work by anyone’s standards. What happens under these circumstances is appalling.

In June 2024, we held a study session at the National Diet to consider working styles. When we called on freelance creators, a wide range of professions came together, and about 100 people gathered, including actors, voice actors, idols, singers, rakugo performers, manga artists, illustrators, designers, proofreaders, film directors, directors, staff, managers, and journalists.

The cases reported here were as follows. “A band group that can no longer use their stage name and is fighting in court to keep it,” “A historian who was removed from the compilation committee when he protested against being asked not to exercise his moral rights in writing a history of the local government,” “An artist who went to France and is working with his friends to draft guidelines for artists’ compensation in Japan,” “A former actor who supports second careers for retired entertainers who have difficulty finding work again,” “A deaf film director who suggests that cultural enrichment could be expanded by creating a work environment where minorities can collaborate on an equal footing,” “A producer who noticed the contrast with Japan when film production crews in Korea and France were provided with freshly cooked hot meals and a flexible schedule that allowed her to balance filming with child care,” “A European award-winning film director is paid only 300 yen per hour,” “A filmmaker seeks cooperation beyond the boundaries of local governments and government ministries to film in rural areas,” “Drivers who continue to support the entertainment industry, which requires a lot of travel and transportation, are facing the problem of the 2024 working hour regulations[4] and the conversion of location buses to white buses[5] (white number plates),” “Approximately 20% of mini theater operators across the country are facing financial difficulties due to their inability to invest in digital projection equipment,” and so on. The problems are piling up.

These problems are incredibly diverse, but they share commonalities that make them difficult to solve. The problem is that because the people who perform these tasks are freelancers, it is difficult for them to collaborate and speak up.

What we can expect from now on

Our organization has experienced accidents and other issues both before and after the establishment of the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance. There are many people who complain about the shortcomings of a newly enacted act or a system that has just started. However, people who have done their daily work and lived a life of hard work and ingenuity in an environment where there are no rules look for anything that can be useful, use it well, and protect themselves wisely. They value their friends with whom they can share information, and even if they are deceived and fail once or twice, they do not give up and become wiser. Even if there are no rules in society, they make rules for themselves. Artisans have that kind of strength and toughness.

One of the hopes we have now is that we can speak out. In the future, as the Freelance Act comes into effect and the government’s health and safety initiatives progress, it will be possible to report violations or accidents to the appropriate government agency. Whether such a breakthrough happens or not will make a big difference.

In June 2024, Upper House Councillor Nakajo Kiyoshi, who has been an actor for many years, said in the Diet, “When I was active, there was no such thing as workers’ compensation insurance or a solid mutual aid organization.” “Times are changing, and I think it’s very good that the scope of security is gradually expanding in this way. […] There is a place where like-minded people on the same artistic path can expand their circle of help and consult with each other, and that is the most important thing.”

People in other industries may think that this is still the case. But how many people have been hurt and left the industry because they had no one to talk to about their problems? The number is incalculable.

Now that a clue to the solution has been found, it will undoubtedly help them, allow them to work with peace of mind, and ultimately lead to a step on the path to saving the entire industry and ultimately Japanese culture.

There is great hope for how much those working in the gray area, neither freelancers nor employees, will be able to grow with the new acts and guidelines.

Translated from “Geino-jujisha wa Uttaeru (Entertainment workers appeal),” Sekai, November 2024, pp. 181–189. (Courtesy of Iwanami Shoten, Publishers) [December 2024]

[1] Akabou is a cooperative formed by individual business owners engaged in light cargo [kei truck (up to 660 cc)] transportation.

[2] The 10th Survey on Activities and Livelihoods of Performing Arts Performers and Staff (2020), Japan Council of Performers Rights & Performing Arts Organizations

[3] “Report on the Labor and Social Survey to Grasp the Actual Conditions of Death from Overwork, etc. in FY2022 (Survey of professionals in the arts and entertainment industries),” 2023 Social Science and Occupational Health Research Group, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, Japan. Other survey results are from the General Incorporated Association of Arts Workers Japan (2021–2023).

[4] Issues arising from the limit of truck drivers’ overtime work to 960 hours per year from April 1, 2024.

[5] This refers to vehicles that transport people for a fee using private cars or rental cars (white number plates) without permission from the Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, and violates the Road Traffic Act. License plates of approved vehicles are green.

Keywords

- Morisaki Megumi

- actor

- General Incorporated Association of Arts Workers Japan

- industrial accident compensation insurance

- arts workers accident compensation insurance

- entertainment industry

- entertainment workers

- self-employment

- entertainment agency

- contract

- freelance

- Agency for Cultural Affairs

- accidents

- health management

- suicide

- death from overwork

- karoshi

- harassment