The Future of Development Cooperation: Don’t tie ODA to security

The Cambodia-Japan Friendship Bridge spanning the Tonle Sap River in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, was opened on February 26, 1994 with the support of the Japanese government.

Photo: ty / PIXTA

Key Points:

- The Development Cooperation Charter is part of the national security strategy.

- Offer-type cooperation is more binding than the tied aid.

- The Japanese people also value “honor in the international community.”

“We desire to occupy an honored place in an international society.” These words from the preamble of the Japanese Constitution seemed to the author, as a student in the 1980s, to be a natural purpose for Japanese development aid.

In the late 1980s, Japan was the world’s second-largest economy in terms of gross national product and was on the verge of becoming the world’s largest donor of official development assistance (ODA). Many “Japan in the World” events were held, and there was a growing momentum that “Japanese people should not only think about Japan, but act as members of the world.” The first ODA Charter, established the following year, embodied Japan’s determination to assume such “responsibility in the world.”

However, the Development Cooperation Charter, which was approved by the Cabinet in 2015 to replace the Official Development Assistance Charter, drastically changed the main purpose of international cooperation. Since the new charter, the government has downplayed development cooperation as a mere part of Japan’s security policy.

The National Security Strategy (NSS), which was first established at the end of 2013, states that “the Strategy, as fundamental policies pertaining to national security, presents guidelines for policies in areas related to national security, including sea, outer space, cyberspace, official development assistance (ODA) and energy.” This was the basis for the 2015 Development Cooperation Charter.

The NSS was revised in 2022, and as a result, the Development Cooperation Charter was also revised in 2023. The 2023 Development Cooperation Charter emphasizes cooperation for peace, economic security, and human security, with “security” at the core of its content.

Another notable difference from the previous ODA Charter is that the Development Cooperation Charter places Japan’s “national interests,” including security, at the forefront. In particular, the 2023 Charter uses the phrase “to contribute to the realization of Japan’s national interests” in addition to “to contribute even more actively to the formation of a peaceful, stable, and prosperous international community,” marking the first time that Japan’s national interests are explicitly stated as an objective of development cooperation.

◆◆◆

And as a concrete measure for this “realization of Japan’s national interests,” the 2023 Development Cooperation Charter includes “offer-type cooperation” (revised to include the Co-Creation for Common Agenda Initiative in October 2023) for the first time. To explain the meaning of “offer-type cooperation,” it is necessary to explain yosei-shugi (the “request-based” principle) for deciding on aid projects, which Japan has long upheld, and the untied principle for material procurement, which the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has called for.

First of all, yosei-shugi means that aid projects are decided “based on the requests of the governments of the recipient countries.” This is the principle that the needs of the recipient countries, not the circumstances of the donor countries, should be considered first when deciding on projects. This is also known in the OECD as the “ownership principle” and emphasizes that aid projects are owned by the recipient countries.

Next is the untied principle, where the word “tied” refers to “the source of materials needed for aid projects.” Tied aid is a type of aid that limits (ties) the source of materials to companies in the donor countries, while untied aid is aid that does not limit the source of materials.

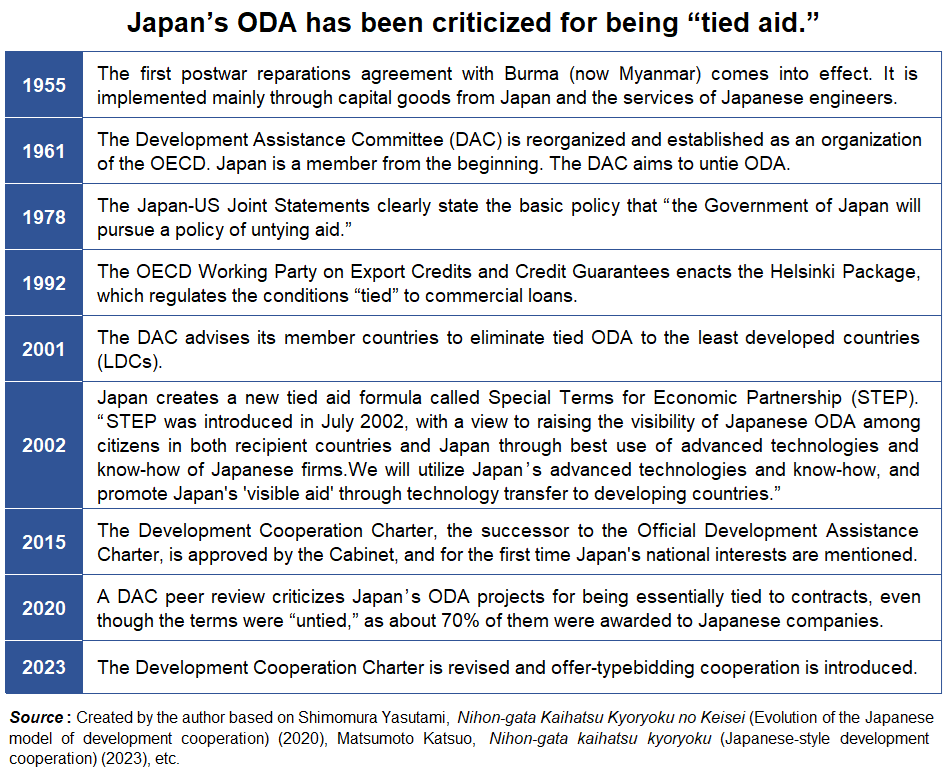

The OECD has urged member countries to increase the proportion of untied aid, which allows recipient countries to choose the most appropriate source of materials from a wide range of options, taking into account the convenience of the recipient countries. As shown in the table, since the establishment of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) within the OECD in 1961, Japan has also sought to increase the proportion of untied aid. In 1978, amid rising expectations for Japan’s international contributions, Japan announced its intention to move toward untying aid in the Japan-US Joint Statement.

In this way, by pursuing both yosei-shugi and the untied principle, Japan has been able to assert that its development assistance contributes to the development of recipient countries.

On the other hand, the offer-type cooperation introduced in the 2023 Development Cooperation Charter differs significantly from both the yosei-shugi that Japan has upheld and the untied principle that it has tried to adhere to. Offer-type cooperation means that Japan proposes (offers) a project before the recipient country makes a request. Examples of government agencies that make offers include the Japan Bank for International Cooperation and Nippon Export and Investment Insurance.

In the future, these government-related agencies will propose projects, and recipient countries will have to accept them whether they like it or not. Japanese companies are expected to win contracts for these projects. In 2002, Japan created a new tied aid system called “Special Terms for Economic Partnership (STEP)” (see table). The purpose of this system is to make “best use of advanced technologies and know-how of Japanese firms,” and it justifies the use of Japanese companies and Japanese products as a matter of course.

In this way, offer-type cooperation essentially imposes on recipient countries not only Japanese products but also the planning of aid projects. This makes it more restrictive than traditional tied aid and more like “aid on a leash.” Recipient countries would not be able to refuse if they were asked to implement Japan’s offer-type cooperation projects in addition to the projects they have requested.

Perhaps sensing such criticism, the 2023 Charter uses the word “co-creation” to create the image of “Japan and recipient countries creating together.” However, even under the yosei-shugi system, the Japanese government had the authority to narrow down the projects to be adopted from the request list, and Japan’s will was strongly reflected in this. Offer-type cooperation does not weaken the injection of Japan’s will, so even if the Japanese government tries to cover it up with the beautiful word “co-creation,” there is no doubt that the recipient countries will feel that Japan is taking a self-centered stance.

◆◆◆

The author believes that Japan’s international cooperation should truly be for the benefit of the partner country and the international community. Some may counter with the following: “Today’s Japanese people are busy with their daily lives and have no desire for honor in the international community,” or “Japan has been overtaken by emerging nations in many areas. They are preoccupied with boosting their own economy and maintaining peace.”

The author doesn’t think so. For example, after an international soccer game, Japanese spectators have a habit of picking up trash around their own cheering section after the game, regardless of whether they win or lose. And many Japanese people praise this on social media. The author interprets this movement as coming from a simple morality. “Do what you should do” and “Do what is natural for a human being.” Many Japanese people have such simple feelings and are proud to act on them. Similarly, the author believes that one of the main motivations for international cooperation is a pure spirit of mutual help.

As mentioned at the beginning, development cooperation policy is currently positioned as part of national security policy, which the author believes is different from what many Japanese expect from international cooperation.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 30 October 2024 under the title, “Kaihatsu Enjo no Yukue (II): ODA, Anpo ni Genteisuruna (The Future of Development Assistance: Don’t limit ODA to security),” The Nikkei, 30 October 2024. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Yamagata Tatsufumi

- Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University

- international cooperation

- development cooperation

- security policy

- ODA

- development assistance

- tied aid

- untied aid

- Development Cooperation Charter

- national security strategy

- national interests

- yosei shugi

- request-based

- offer-type

- ownership principle

- untied principle

- mutual help

YAMAGATA Tatsufumi

YAMAGATA Tatsufumi