(NO CONFLICTS DESIRED) Don’t Disrupt Exchanges Now–Japan, China Must Aim to Be "Great Countries of Peace" in East Asia

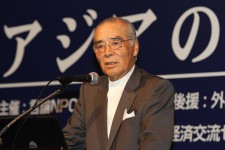

Kobayashi Yotaro

Sharing Vision of Peace, Civilization, Friendship

With the objective of promoting development and friendship between Japan and China, “The New Japan-China Friendship Committee for the 21st Century” was formed in 2003 as a private advisory panel to both governments. The foundation of the council was agreed on at a Japan-China summit held in May the same year. For five years up to 2008, I was involved as the chairman of the Japanese side.

Although I had relations with China on a business basis, I myself was not an expert on China. But I undertook the duty partly because I had wanted to realize the expansion of existing exchanges with China. Together with the other council members – Tadashi Sonoda (NHK commentator), Makoto Iokibe (then president of the National Defense Academy of Japan), geophysicist Takanori Matsui (professor at the University of Tokyo), writer Yoshimi Ishikawa, economist Motoshige Ito (professor at the University of Tokyo), astronaut Chiaki Mukai and political scientist Ryosei Kokubun (then professor at Keio University) – as well as members of the Chinese side, we conducted frank discussions and exchanges in eight rounds of meetings over the five years starting with the first session in Dalian. Open symposiums and other events were held in various places, and we issued numerous statements. To our satisfaction, achievements were also seen in youth exchange programs.

What I myself have gained through these experiences was considerable. Among other things, it was of great significance to me that I enjoyed the favor of Zheng Bijian, who chaired the Chinese side. Chairman Zheng is the former executive vice president of the Central Party School of the Communist Party of China’s Central Committee, and then Chinese President Hu Jintao and numerous other prominent figures studied under his tutelage. At a gathering in Beijing before the first meeting for committee members from both sides to get acquainted, his preeminence and regal presence impressed me and remained in my memory. Unfortunately I am not able to speak Chinese and he cannot speak Japanese. However, through the discussions and exchanges during the five-year period, my confidence in him became unshakable. He is a man who combines extensive knowledge, profound intellect and appropriate decision-making ability.

Due to the visit to Yasukuni Shrine by Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi at that time, the two nations were a situation of disrupted summits between their leaders. But later Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (during his first administration) visited China, and a “mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests” – a concept which has become the key to bilateral relations – was worked out in a move toward improving ties.

At the fifth meeting of the committee held in response to this move, we had the opportunity to meet then Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao. Just as we were leaving after a prolonged earnest talk which overran the initially set schedule, I conveyed our hope that he would visit Japan, although it could be said that this was a “diplomatic nicety.” His reply through an interpreter was, “If conditions are met, I will visit Japan.” While trying to figure out the meaning of “conditions” on the way back, the director of the Japan division of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs telephoned me and explained to me, “Regarding Premier Wen Jiabao’s reply, to give his thoughts precisely in Japanese, they would be that ‘the pathway has already been prepared, and in line with that tide I will visit at the right time.'” The official mentioned that it was difficult to translate partly because Wen had quoted an old Chinese saying.

The 21st century committee promoted political, economic and cultural exchanges with the objective of promoting peaceful coexistence, generation-to-generation friendship, mutually beneficial cooperation and joint development for Japan and China. However, despite the gains, some issues remain divisive between the two sides. It was in the midst of the Yasukuni issue and at times Chinese delegates made harsh comments against the Japanese government. But with his outstanding leadership, Zheng led the group in a positive direction whenever discussions became heated.

At one of the meetings, I mentioned that the two nations have various differences in political, social and economic areas and that these gaps at times create frictions. Given China’s rapid economic development, cases in which these frictions become noticeable are increasing. At the same time, there are occasions when problematic remarks concerning history emerge from Japan. Despite all this, we (the council) have to build up a relationship of political, economic and cultural cooperation not only for future generations but also for Asia and the whole world. To achieve this goal, it is important to clarify the direction our countries want to take. Against this backdrop, I proposed the need to clarify which direction the two sides are heading in. My intention was to question what kind of a country China wants to be.

Should the directions of both countries become clear, and be shared, the significance of a cooperative relationship between the two will probably not be lost even if the path and ways of reaching the goal are different.

Zheng totally agreed with the proposal and he clearly pointed out three directions in which China is heading. That is to say, China is aiming to be a “major nation of peace”, “major nation of civilization” and “friendly major nation.”

Regarding the first goal of a “major nation of peace,” there is absolutely no point in objecting, needless to say, as Japan treasures peace and has been enjoying it during the post-World War II era under its pacifist Constitution.

The second goal of a “major nation of civilization” has aspects Japan can share. It has learned many things from other countries and built up a civilization in which it could take pride.

The third goal is also an important one for Japan, which is perceived as a country with “no friends in Asia despite its economic development.”

Therefore, Japan and China can share this vision of developing together as peaceful, civilized and friendly major nations. Various obstacles and issues may emerge, but the only way to deal with them is for both sides to look calmly at the facts and continue candid and constructive dialogue. Constructive dialogue to resolve these problems is exactly what is needed to create the foundations of the bilateral relationship.

Quest for New “Mutual Interests”

The aggravating Senkaku situation has come to the forefront of Japan-China relations, but losing sight of “mutual interests” is undesirable for the future of both countries. The concept of a “mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests” is supposed to be about relations for pursuing common interests from a medium- to long-term viewpoint.

My friendship with Zheng continues even after the committee’s five-year activities have ended, and at his invitation some former members and I visited China in January last year. At that time, Zheng said that although various minor issues which may cause conflicts and frictions exist between the two nations, it is vital to take concrete actions regarding mutual interests, raising renewable energies as one of the major themes which require the two nations to team up.

Needless to say, the energy problem is a crucial theme for both countries. It was one of the major issues taken up at the council meetings during my chairmanship. From the viewpoint of preventing global warming, coal-burning thermal power generation as a major power source is now questionable, and after the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011 nuclear power has also become an issue. Tangible progress in the bilateral alliance in the field of clean energy is hoped for. Energy is exactly the area in which the two nations should promote strategic cooperation from medium- to long-term perspectives.

There are many other themes that have such positive implications for the two nations. It is extremely regrettable, however, that their cooperation and partnership does not move forward due to the worsening Senkaku situation. The Japanese government’s purchase of some of the Senkaku Islands from their private owner last September was undoubtedly intended for the sake of bilateral relations and was also not a proactive move by the government. But it turned out to have a negative impact, leading China to disregard commemorative events for the 40th anniversary of normalization of bilateral diplomatic relations, an unprecedentedly unusual situation. Furthermore, exchanges in numerous areas have also been forced to be suspended. I argue, however, that exchanges should not be disrupted precisely because we are in such a period of time.

In mid-September last year, I had an opportunity to visit Beijing regardless of the serious circumstances. I met Zheng and asked him what he thought of the situation. He said there are three possible outcomes. The two undesirable situations are a total cold war and an occurrence of a partial war, which must be avoided. The third possibility, he said, is to use the occasion to put mutual interests into the spotlight and move forward.

Demonstrations and riots do not continue forever. They will disappear as time passes as long as Japan avoids taking any provocative action. Although multiple blows were suffered, they also are not everlasting. Obviously, the situation in waters surrounding the Senkaku Islands must not necessarily be taken for granted, and China’s reaction has become more rigid than ever before. On the other hand, Tang Jiaxuan (president of the China-Japan Friendship Association) has shown his willingness to meet the representatives from seven friendship organizations and the business community in Japan, suggesting that the will to sustain exchanges with Japan has not disappeared from China.

The leadership has changed in China, and the administration has also shifted in Japan. What is critically important now is what policies the leaders of the two countries will take. In China, some of the policies regarding Japan may be beyond our imagination and it impossible to take all of them into consideration. Even if this is the case, our underlying principle must firmly remain the goal of becoming a major nation of peace, and this must not waiver.

There are undeniably moves by some in both countries which may lead to an outbreak of heated battles. However, we should envisage our mutual interests as being big enough to crush and wash away such moves. A bilateral partnership in the area of clean energy is expected to be one of them.

Fostering Literacy and Liberality

Considering the future of Japan and China, the top-priority issue we have to tackle from a medium- to long-term viewpoint is mutual exchanges, especially among the young generation. It may be hard to obtain popular understanding of youth exchange programs amid persistent media reports about demonstrations in China. But exactly because of such a situation, the programs should be carried out boldly and uninterruptedly. Building human-to-human relationships is the foundation for all kinds of matters.

The Senkaku situation cannot be resolved so easily. However, it does not mean that unless the situation settles down, exchange programs cannot be conducted. Rather, as trust develops through such exchanges we may find an approach to solving these complex problems. Positive themes, not negative ones, must be taken up, such as private-level cultural and economic exchanges, and a partnership for renewable energy.

Such broad private-level exchanges and the presence of trust as well as continuing efforts in pursuit of common interests will be crucial for the two nations to smoothly implement their foreign policies.

Diplomacy is undertaken by people. Especially in the current complicated circumstances, competent diplomats are needed for negotiations. However, some in Japan tend to criticize the so-called “China school” diplomats in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, arguing that they are probably following whatever China says in disregard of the “national interests” of Japan. Diplomats fluent in Chinese and deeply versed in Chinese history and culture should engage in negotiations on the front line, pursuing resolutions while obtaining trust from the other side. This is what is normal in the world of foreign affairs. Needless to say, the Chinese side must also assign diplomats who can speak Japanese and understand Japanese culture and history to posts related to Japan.

Diplomatic negotiations to bring down a fist that has been raised are indeed extremely difficult. Criticizing diplomats who know the other party’s situation well and excluding them will preclude rational diplomacy. The Senkaku situation in particular requires a calm response without being emotional and endangering the medium- and long-term mutual interests of both nations. On top of that, the wisdom and human networks of China experts as well as those who have engaged in friendship exchanges with China for a long time must be respected.

To be sympathetic with “brave” arguments attacking a “weak-kneed stance” is easy, but we should calmly consider whether a “tough stance” will bring about a favorable outcome. Demonstrations and riots in China led to negative reactions from the international community. The same happened after outspoken remarks made by the Japanese side. The violence of the demonstrations evoked criticism even in China. We must deepen ties among the people, who are rational and prudent.

Lastly, I would like to refer to my essay published in November 2005 (in monthly magazine Gaiko Forum) when the relationship with China was at difficult stage.

Journalist Kiyoshi Kiyosawa, who criticized Japan’s continental and U.S. policies and continued to call for avoiding war both before and during World War II, repeatedly pointed out in his book “A Diary of Darkness” that the main reason why Japan made such a mistake in national policy was the problem of education. In his diary entry dated Feb. 15, 1945, Kiyosawa wrote, “Education has been defeated. This is the result of learning without ideas and cultivation and more acquisition of ‘skills’.”

In using history as a mirror, I want to ponder the meaning of his words. This is because postwar Japan has leaned more than in pre-war times toward “skills” instead of “cultivation.”

What, then, is “cultivation.” One philosopher defines the term as “the nurturing of academic capability and intellectual tolerance which enables understanding of the position of the other side even when not agreeing with the position, as well as the ability to communicate.” According to this definition, if you understand the position of your opponent, you will be able to engage in dialogue without arguing, thus enabling you to pursue “sublation” and overcome each other’s stances and way of thinking.

In considering Japan-China relations from a long-term and strategic standpoint, I believe that the ultimate challenge, even if it may be a roundabout and time-consuming approach, is to foster highly literate leaders who have studied comprehensively the liberal arts of both countries – their culture, history, language and philosophy – and have the ability to communicate with the other party. This is fundamental for building deep relations with China, and it goes without saying that the same applies to Japan’s relationships with other nations.

====================

Translation of an article (pages 97-102) from the November 2012 issue of the magazine SEKAI (Iwanami Shoten Publishers)

Born in 1933 in London, Yotaro Kobayashi graduated from the Faculty of Economics at Keio University in 1956 and earned his MBA at the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce at the University of Pennsylvania in 1958. He joined Fuji Photo Film Co. the same year. Moving to Fuji Xerox in 1963, he became president in 1978 and later assumed the posts of chairman and chief advisor, before retiring in March 2009. He served as chairman of the Japan Association of Corporate Executives (1999-2003) and assumed the post of lifetime trustee of the organization. He is also chairman of the International University of Japan.