Enigmatic Picture Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans

Hashimoto Mari, Vice-chairperson of Eisei Bunko Museum

Scene of a rabbit and a frog sumo wrestling from the Ko-kan, scroll no. 1 of the Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans

Source: Kosanji Temple

Hashimoto Mari, Vice-chairperson of Eisei Bunko Museum

About a one hour bus journey from Kyoto station, where the mountains that extend across the Tanba Highlands adjoin the Kiyotaki river and form valleys, in an area known for its autumn leaves and beautiful valleys, stands the ancient temple of Kosanji. It is thought to have been built around the 8th century as a Buddhist monastery called the Toganoo, but by the end of the Heian period (794–1185) when it became the branch temple of the Jingoji temple over the mountain, it had so fallen into ruin as to be unrecognizable. Jingoji also fell into ruin and a priest named Mongaku (1139–1203) busied himself with its restoration. Mongaku repaired Toganoo and arranged for it to become an independent temple for the monk who was expected to be his successor, Myoe (1173–1232). In this way, when in 1206 the retired Emperor Go-Toba granted the land of Toganoo and the name Kosanji, the temple’s history up to the present day began.

It was a temple of scholarship that over time amassed many sacred texts, writings, documents, works of arts, and craft items. But among these, the most famous is a set of four very long picture scrolls produced from the end of the Heian period to the Kamakura period (1185–1333) known as the Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans (Frolicking Animals for short). Each of the four scrolls is 10 to 12 meters in length, drawn in lines of black ink without color or accompanying verses, and shows various kinds of animals and humans frolicking about. To distinguish the scrolls, they are classified as the Ko-kan (scroll no. 1), Otsu-kan (scroll no. 2), Hei-kan (scroll no. 3), and Tei-kan (scroll no. 4) volumes.

The Ko-kan (no. 1) has a famous scene of a rabbit and a frog sumo wrestling while a rabbit and frog pursue a fleeing monkey, which many people quickly recognize as from the Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans—anthropomorphized rabbits, monkeys, and frogs that run about in a small space. The Otsu-kan (no. 2), on the other hand, portrays in a non-anthropomorphized way the real animals of horses, cows, hawks, dogs, chickens, but also qilins (a one-horned chimera), dragons, lions, elephants, baku (a fantastical tapir), animals that don’t exist in Japan or are imaginary sacred beasts. The first half of the Hei-kan (no. 3) has scenes of humans playing games such as go, sugoroku (Japanese backgammon), and shogi (Japanese chess). The second half is drawn with anthropomorphized animals playing kemari (a football game of the ancient Japanese court), racing horses, and pulling festival floats. The Tei-kan doesn’t have pictures of animals, but shows a series of humans doing acrobatics, holding Buddhist funerary services, and performing horseback archery.

Scene of cows locking horns from the Otsu-kan, scroll no. 2, 9th to 10th sheets

Source: Kosanji Temple

The scattered pieces of a puzzle

Thus, detailing it in writing, we can see that each scroll has its own distinct individual character. Although there’s a tendency to assume that they were made as a set from the first, in fact each scroll has a different production time, subject that is drawn, paper quality, etc. It seems that each scroll was produced on a different occasion according to a different plan, was collected at Kosanji during a different period, before coming to be seen as a single set of scrolls. What’s more, there are various “puzzle pieces” scattered about with a very close relationship to the Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans outside Kosanji, such as paper fragments separated from the set of scrolls and copies of the scrolls containing drawings of scenes not in the current scrolls, i.e., of scenes that became fragments and were lost. Researchers have spent many years fitting these clues together and attempting to clarify the nature of the Frolicking Animals. Yet, the basic facts are still not known: When were the scrolls made and by who? Why did they make them? Who was the artist who drew the scrolls? They are a truly mysterious work.

There was a plan to hold a special exhibition of all four Frolicking Animals in the summer of 2020 at the Tokyo National Museum, to coincide with the staging of the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics. But due to the effect of the spreading COVID-19 pandemic there was no choice but to postpone the exhibition and it was held nine months late from April 13 to June 20, 2021. Originally this would have been a chance to show the scrolls to guests visiting from over the world, but there were almost no visitors to the museum from abroad, and in fact the scrolls had to be shown to a severely limited number of museum visitors.

This was certainly a shame, but in reality the Frolicking Animals have been shown overseas a number of times. It started with them being shown at the Exposition Universelle (1900) in Paris (Kosan-ji version, Volume 3?). After that, there are records of the Japan-British Exhibition in 1910 (Kosanji version, unknown single volume), The Special Loan Exhibition of Art Treasures from Japan held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1936 (fragment, Tokyo National Museum version), the exhibition “A Survey of Japanese Art” held at the Seattle Museum of Art in 1949 (fragment, Tokyo National Museum version), the “Exhibition of Japanese Painting and Sculpture” which traveled to five American museums in 1953 (Kosanji version, Volume 1), the René Grousset Memorial Exhibition at the Musée Cernuschi in Paris in 1954 (fragment, Tokyo National Museum version), the “Traveling Exhibition of Japanese Antique Art to Europe” in France, UK, Netherlands, Italy from 1958 to 1959 (Kosanji version Hei-kan and Tokyo National Museum version fragment), and the “Traveling Exhibition of Japanese Antique Art to the United States and Canada” which traveled to four museums in the United States and Canada in 1965 and 1966 (Kosanji version, Volume 3). (Source: Kito, 2021)

Kicking off with the “Special Loan Exhibition in Commemoration of the Signing of the Peace Treaty in San Francisco” at the De Young Museum in 1951, most of these overseas exhibitions were sponsored and held by the Agency for Cultural Affairs “to introduce our country’s superlative cultural properties to foreign nations, to deepen understanding of Japan’s history and culture, and to further international cultural exchange.” In any case, it is clear that both at home and abroad the Frolicking Animals was considered a masterpiece essential for anyone unravelling the history of Japanese painting.

Disassembling the enigmatic picture scrolls

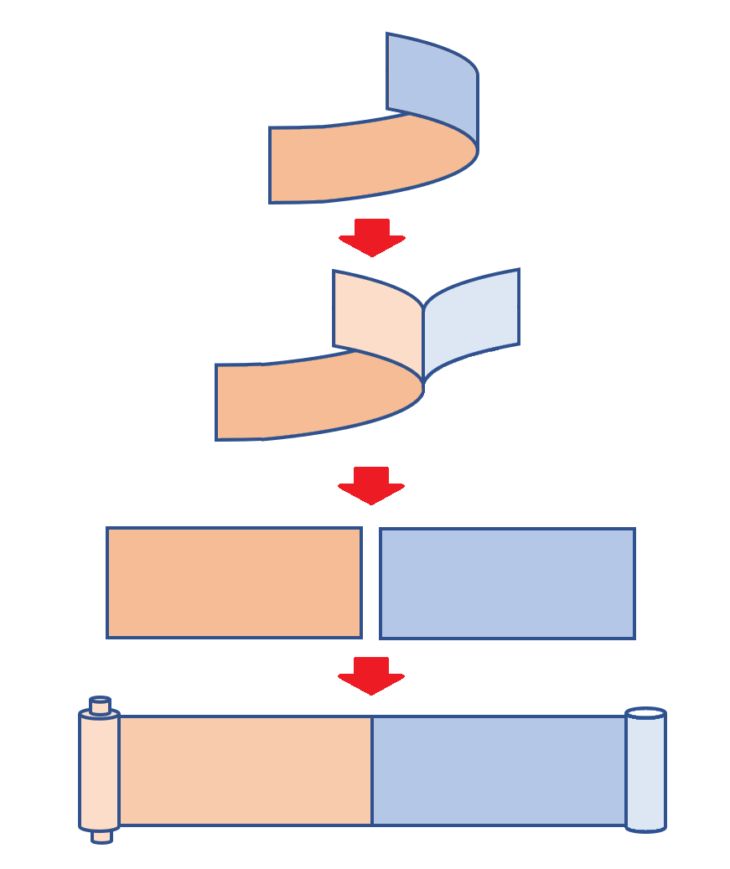

The picture scrolls are as wrapped in mystery as they are famous. The impetus for the mist surrounding the scrolls to gradually lift was a four year (2009 to 2012) full-scale scale restoration—the first for around 130 years. The Frolicking Animals and other picture scrolls are made as long scrolls of washi (traditional Japanese paper) sheets (each about 50 cm wide by 30 cm) pasted together with rice glue. As part of the disassembly and restoration, one by one all the paper sheets were separated and the thin washi urauchi paper backing sheets used to strengthen the scrolls were removed. Water was sprayed onto these now “naked” main sheets (the washi paper with the actual words and drawings) to remove dirt, then a detailed survey took place.

Various new facts—small to large—were ascertained at this time. Readers who are interested in the details may consult the full restoration report, but now I’ll introduce a few interesting discoveries related to the Ko-kan (no. 1) and Hei-kan (no. 3) scrolls. And after that I’ll share some hazy glimpses of the scrolls’ beginnings.

The disassembly of picture scrolls, which as I described before are made from sheets of washi paper, is not a much harder task that one might ordinarily imagine. The more admired the work is the more inevitable it is that someone turns up who wants to own even just a piece of it, and it’s not unusual for unfortunate unintentional accidents to result in parts disappearing.

I don’t know what the circumstances were, but, for example, in the Ko-kan (no. 1) scroll a scene of a monkey dressed as a monk receiving offerings after a Buddhist memorial service is in two separate places with a slight gap. In Japanese, this mix up in the order of illustrations in a picture scroll is common and called “sakkan,” and to prevent mistakes the joins between sheets of paper are marked with numbers or stamped with seals. The vermillion Kosanji seals that can be seen on today’s Frolicking Animals were applied for that reason.

Working on these assumptions, and based on a match in paper quality that went as far as lines in the fibers created when the washi paper was strained, strong backing was found for a hypothesis that three fragmentary leaves owned by the Tokyo National Museum (Tokyo National Museum version) previously fit in before the 16th sheet of the Ko-kan (no. 1) scroll.

Also, based on a copy (Sumiyoshi version) thought to have been made before these fragments became detached, it is thought that a scene from the beginning of the Ko-kan (no. 1) scroll of a rabbit and monkey playing in water was preceded by a scene of a rabbit, monkey, and frog playing in boats. Additionally, based on a different copy (Nagao version), it is supposed that scenes of playing go, neck pulling (when two people tie their necks together with cords and play at tug of war), and high jump, which are scenes that don’t currently exist as a fragment, came in-between the 19th and 20th sheet of the current Ko-kan (no. 1) scroll, and that there were other final scenes, which also don’t exist in current versions, of un-anthropomorphized realistically drawn snake appearing and frogs who were watching dengaku (ritual religious music and dancing) run away in confusion.

Based on these drawings that don’t exist now and changes in order, a supposition from drawing styles that there were probably two artists, and other factors, a possibility has arisen that what we must call the “original” Ko-kan (no. 1) scroll was composed as two or three separate scrolls.

Scene of a party of frogs headed by a Buddhist priest wearing a lotus leaf on his head who have come to support other frogs in a battle with monkeys using Buddhist powers, from the Hei-kan, scroll no. 3, 19th to 20th sheets. The monkeys appear in the 18th sheet.

Source: Kosanji Temple

Next, something even more surprising was discovered about the Hei-kan (no. 3) scroll. The first half of this scroll (1st to 10th sheets) is drawn only with humans, in other words, comic pictures of humans. The second half (11th to 20th sheets) is composed of anthropomorphized creatures in action, i.e., comic pictures of animals. Yet, from things such as the inscription at the end of this scroll that says, “treasured and treasured picture rolls/four rolls gathered/May Kencho 5/Takemaru [written seal],” and the count of 14 sheets as of 1253, there is a discrepancy with the current number of 20 sheets.

This contradiction has been much debated, but as a result of the disassembly and repair, it was realized that from a picture on sheet one and stains on sheet 20, and a picture on sheet two and stains on sheet 19, that stains dotted around the comical animal pictures in the second half of the scroll exactly fit the comical human pictures in the first half. In other words, the human pictures and animal pictures were initially painted on the front and back of one sheet and in places the ink has soaked through. That means that these sheets of paper were split into separate front and back sheets using a technique known as aihagi (paring) then joined up to be remade as the single scroll that is the current Hei-kan (no. 3) scroll. Although at first the 14 sheets of paper made a single scroll, at some point four were lost and it became 10 sheets long. The front and back of those 10 sheets were separated via the aihagi technique and the scroll was recreated as one of 20 sheets. Aihagi is a technique possible only because of the way the fibers of washi paper are layered, but it’s a somewhat unexpected “major surgery” to the scroll.

Scene of a man who lost a game of sugoroku (Japanese backgammon) and was thus relieved of his clothes, from the Hei-kan, scroll no. 3, 2nd to 3rd sheets. (Restored after using the aihagi technique for splitting scroll paper from its backing paper.)

Source: Kosanji Temple

In addition, by putting together old and new knowledge, such as the possibility that the artists of the Ko-kan (no 1) scroll and the Otsu-kan (no. 2) scroll are the same individual, or that the content of the Hei-kan (no. 3) scroll is influenced by the Ko-kan (no. 1) scroll, and that the artist of the Tei-kan (no. 4) saw the Ko-kan (no.1) scroll and parodied it, researchers have supposed that, even if the scrolls weren’t drawn by the same person during the same period, that the scrolls came into existence in close relationship to one another, and that they came to be considered a single set of four scrolls at the time of a major restoration that took place during the Edo period (1603–1867), before coming down to us today in that form.

Remaining mysteries

The oldest reference to “Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans” is the 1253 inscription at the end of the Hei-kan (no. 3) scroll. The name was not fixed and, along the lines of “picture scrolls,” this work was known as “joke pictures,” “animal pictures,” or “Toba pictures” (after a legendary attribution to an artist-monk called Toba Sojo [bishop of Toba, 1053–1140]). It is only since early modern times that they have been named Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans. Up to and during the medieval period they were barely known, and it was only from the start of the Edo period (1603–1867) that a certain number of copies were made.

It is also not clear when they were inherited by Kosanji temple. Although there is much talk of a connection with the extremely distinguished monk Myoe, in the Kosanji library catalog that was compiled by his disciples after his death, there is no such reference to the scrolls. It is likely that the Ko-kan (no. 1) and Otsu-kan (no. 2) scrolls—and maybe the Hei-kan (no. 3) scroll—were produced before the revival of Kosanji, and that they came to Kosanji after Myoe’s death, so there doesn’t seem to be a direct connection. However, Myoe laid the foundations for Kosanji to be a temple of scholarship and afterwards it continued to be a “Buddhist research center with an attached general library” (Tsuchiya, 2021), and so, like a magnet, it drew many books and cultural properties to be collected there. We can assume that the Frolicking Animals was one of these.

Of the Buddhist temple buildings that once crowded the temple precincts, all except the Sekisuiin (a national treasure dating back to the Kamakura period [1192–1333]) were burned in the fires of war and completely destroyed. But during each fire the temple monks rescued temple treasures such as huge books, Buddhist paintings, and the Frolicking Animals from the conflagration, and they have survived until today. The Frolicking Animals tends to be discussed from a perspective of primitive animism and deep affection for animals, and that is not a mistake. But judging the process of origin now becoming clear, and temple records which state, “We have managed to gather the Frolicking Animals from the flames of war,” we can perhaps sense a situation of more complicated nuances, as well as earnest passion towards Buddhism on the part of Myoe and other monks.

References

Special exhibition Masterpieces of Kosan-ji Temple: the complete scrolls of Choju Giga, Frolicking Animals, Tokyo National Museum, 2015

Chojugiga – Shuri kara mietekita sekai – kokuhou – chojugiga shuri hokokusho [Frolicking Animals – the world newly glimpsed through restoration – national treasure Frolicking Animals restoration report] Supervised by Kosanji temple and edited by the Kyoto National Museum, Enseisha Publishing Inc, 2016

Tsuchiya Takahiro, Nazotoki chojugiga [Solving the mystery of the Frolicking Animals], Geijutsu Shincho, July 2020, p. 57

Special exhibition National Treasure: Frolicking Animals, Tokyo National Museum, 2021

5) Oubei kara mita chojugiga–kidai ni okeru kaigaishuppinn wo megutte– [(5) Frolicking Animals as seen in Europe and the US–regarding modern exhibition of the work abroad] and a 2021 lecture series at the Tokyo National Museum: The Latest Research on the Scrolls of Frolicking Animals, Kito Satomi, 2021, p. 14-15

Translated from an original article in Japanese written for Discuss Japan. [October 2021]

Keywords

- Hashimoto Mari

- Eisei Bunko

- Japanese arts

- Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans

- picture scrolls

- exhibitions

- Tokyo National Museum

- Kamakura period

- Kosanji

- Toganoo

- Jingoji

- rabbits

- monkeys

- frogs

- humans

- monk Myoe

- Buddhism