Changes to the international system due to the rise of China. From trade wars to a “new Cold War.”

Four characteristics of the Trump administration compared to the 1980s

Tanaka Akihiko, President, National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS)

Is this the beginning of a new Cold War? It has now become usual to characterize US-China relations using the term “trade war.” But is the conflict affecting that relationship really limited to trade alone? During the 1980s and 1990s, the United States turned Japan’s trade surplus with the United States into a problem, and trade friction between the two nations intensified. But can we really describe the ongoing US-China trade war as a contemporary version of Japan-US trade friction? Rather, if the current clash between the United States and China is not simply a trade war, and if we were to seek a similar phenomenon, could we not compare it to the Cold War between the Soviet Union and United States? In other words, shouldn’t it be considered the ongoing evolution of a systematic conflict that encompasses both ideology and military and security issues?

President Trump often makes statements to the effect that a balance of trade reflects a nation’s loss or gain. In this respect, the current US-China trade war is similar in many ways to 1980s Japan-US trade friction.

The United States’ trade deficit with the rest of the world during the 1990s was 124.3 billion dollars, while its deficit with Japan was 44.5 billion dollars, accounting for 36% of the whole (according to IMF, Direction of Trade data.) Despite the fact that most economists said that there was no point from the perspective of economics in making an issue of the trade deficit between the two countries, the majority of American politicians sought that Japan should reduce exports to the United States and increase imports. As a result, there was a series of voluntary export restraints on automobiles and other goods, as well as talks on opening Japan’s market to goods such as oranges and beef. During the final stage of Japan-US trade friction, numerical targets were set for the import of US-made semiconductors. Then in 1989 the Japan Structural Impediments Initiative took place: talks that treated the make-up of the Japanese market itself as an issue.

The United States’ current trade deficit with China is also enormous. Looking at the 2017 figures, the United States had a 797 billion dollar trade deficit with the rest of the world, including a 375.2 billion dollar trade deficit with China that accounts for 47% of the whole (according to IMF, Direction of Trade data.) The visit to China this May by a large group of US economic officials, and their demands towards the Chinese side regarding various areas of the economy, is a scene that reminds us of past Japan-US trade friction.

Even from the limited perspective of trade negotiations, however, there are aspects to the current US-China trade war that were not seen in the Japan-US trade friction of the past.

Firstly, President Trump himself rarely refers to the multilateral trade system and has no hesitation in moving forwards with bilateral trade negotiations. No previous US president has shown this lack of interest in the multilateral trade system.

Secondly, the Trump administration is pushing on with bilateral negotiations not just on trade with China, but with all the countries and regions with which the United States has a trade deficit, such as Canada, Mexico, South Korea, the EU and Japan. What’s more, every one of these countries has said that the United States is engaged in “unfair” behavior.

Thirdly, in the case of negotiations with each of these countries, the United States suddenly said it will impose tariffs then forced the other side into talks. In the case of negotiations with China too, the United States suddenly imposed approximately 50 billion dollars of tariffs on Chinese goods exported to the United States and said that, should China retaliate, it would impose a further approximately 200 billion dollars of tariffs on exported goods or, if necessary, put tariffs on all the Chinese goods exported to the United States. During the Japan-US trade friction, various points of agreement were reached before retaliatory tariffs were set.

And fourthly the United States has demanded that China both puts in place regulations to protect intellectual property rights and securely implement them, and stops demanding intellectual transfer to accompany investment from overseas. Furthermore, the nature of its demands has greatly exceeded the scope of previous trade negotiations, including that China stop state support for what one might describe as China’s industrial strategy: Made in China 2025. (According to reports, the United States has even demanded withdrawal of the plan itself.)

An incoherent president vs a judicious political system

When, in this way, we look back at the Trump administration’s trade policies as a whole, there seems to be no clear establishment of priorities and, to put it negatively, the strategy appears incoherent. Probably, it is the personality of President Trump himself that has given rise to these characteristics, as well as the obscurity and uncertainty that distinguishes the running of his administration. It seems that President Trump himself is not unduly concerned about appearing incoherent. That is because it seems he believes the secret of successful “deal making” is not to allow the other party to understand his real intentions.

However, according to media reports since the start of the administration, the book recently published by Bob Woodward, and a newspaper column written by an anonymous writer claiming to be an administration official, is of a situation in which the making of decisions and implementing them is chaotic. The “adults” in the administration are using persuasion and sabotage to somehow avoid President Trump’s impulsive and ill-though-out decisions and to ensure that decisions made by its government do not cause damage to the US national interest.

We really don’t know the truth. But it is gradually becoming clear that there are considerable checks on President Trump’s ability to decide policy. Since he is the president, he has very considerable legislative authority. Yet, various political and administrative processes must be gone through for the personal statements of the president to be implemented as decisions made by the United States. The appointments made by the Trump administration to date have been exceptionally unusual, and the appointment of officials to many key departments still hasn’t taken place. Furthermore, appointed officials continue to resign or leave their posts. Meanwhile, the view of the anonymous writer is that a “quiet resistance” is working to prevent the country making mistakes. Of course, it is not impossible for President Trump to overcome this quiet resistance and see that his orders are implemented. But to date, policies that have not had the agreement of this quiet resistance have been sabotaged or, even when they have been implemented, it seems only to have been in a suitably watered-down form.

Moreover, the administration is not the only entity that can decide US policies. So far, in various ways the US judiciary has checked the implementation of Trump administration policies. Also, Congress has a decisive role regarding US policy. Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 (Commerce with Foreign Nations) of the US constitution gives authority for tariffs and trade negotiations to Congress. While it is possible for an administration to negotiate over trade with various countries, ultimately it is Congress that has the final say. Accordingly, when an administration conducts trade negotiations it is under pressure to make sure the contents of those negotiations are within the limits of Congress’s agreement.

President Trump himself probably dislikes constraints such as these. But that is exactly why the anti-Trump camp in the US consider him dangerous to the nation’s freedom and democracy. If it were possible for Trump himself to act in a way that fundamentally defeated these constraints, he would completely overturn the US constitutional system and destroy the nation’s system of freedom and democracy. Should something like that happen, it would be a massive threat for all those living in systems of freedom and democracy around the world — a much greater disturbance than the rise of China.

While one can’t completely deny the possibility of freedom and democracy being destroyed in the United States, I don’t think it will happen. So far, the Trump administration has not been able to overcome these constraints, and while an anti-democratic trend is not completely absent among hardline supporters of President Trump, there is no particularly obvious anti-democratic movement. If, as anticipated, the Democrats gain a majority in Congress following the November midterm elections, these constraints will become even stronger. It will probably become hard for the administration to implement most of its controversial policies.

In other words, these are the safety valves that the founding fathers incorporated into the US constitution at the end of the eighteenth century. The US constitution was drafted by James Madison in accord with his assumption that an “enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm.” (The Federalist Papers). When an “enlightened statesman” is absent, preventing despotism due to the entire government becoming dysfunctional is a concept that lies right at the heart of the system of freedom and democracy… and a function such as this may be operating right now.

China’s erosion of intellectual property rights and high-tech industries

When it comes to trade policy too, it is very unclear what would ultimately happen should such disfunction occur. Practically speaking, no trade negotiations result in complete free trade or complete protective trade; and there are deals with different degrees of freedom or protection for various goods and services.

Although the deal agreed at the end of August between the United States and Mexico was not desirable from the perspective of those who advocate completely free trade, as a political settlement it was not improbable. The “quiet resistance” may have decided that if they compromise this far things will not be that bad.

In any case, since the long-term economic effects will not appear immediately, if President Trump wishes, he can say that it is a victory for the United States and end negotiations. I believe that ultimately there will be a similar vague agreement when it comes to Canada, the EU and Japan too.

So, what about the trade war with China? Since the United States’ trade deficit with China is far larger than with other countries, resolution of the issue will not be easy. Furthermore, a decisive factor is that US demands on China are qualitatively different to trade issues with other countries. When the Trump administration said it would impose tariffs on steel and aluminum products from the EU and Japan “for security reasons,” many commentators pointed out that it was strange to raise the issue of security regarding steel and aluminum products from ally nations. At the end of the day, shouldn’t trade issues with ally nations be about regulation issues such as jobs rather than security issues? It seems that the first and second distinct features of the Trump administration’s trade policies mentioned above ultimately do not reflect the US national interest, while they push the whole of US society (including forces of resistance) towards a weakened state.

What’s more, the United States is not currently just seeking action related to jobs through its demands on China. Even assuming that President Trump personally thinks job issues are the absolute priority, Chinese industrial development capacity in cutting edge fields is more important from the perspective of the overall US national interest.

This June, the White House issued a report titled: “How China’s Economic Aggression Threatens the Technologies and Intellectual Property of the United States and the World.” According to this report, China steals technology and intellectual property using both physical and cyber means, as well as forcing the transfer of technology to foreign-owned companies by various regulations and domestic measures. In addition, it is collecting information via the huge number of students and researchers based in research institutions in the United States and other nations. What’s more, it is attempting to buy overseas companies with advanced technology through the use of foreign investment by state-owned companies. The report argues that through these activities China seeks to “Acquire key technologies and intellectual property from other countries, including the United States and capture the emerging high-technology industries that will drive future economic growth and many advancements in the defense industry.”

The US National Security Strategy released at the end of 2017 expresses a similar view. It states that “China and Russia challenge American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity. They are determined to make economies less free and less fair, to grow their militaries, and to control information and data to repress their societies and expand their influence.” It indicates the same perception as the White House Report that “Every year, competitors such as China steal U.S. intellectual property valued at hundreds of billions of dollars.”

Also, it seems that these worries about China regarding security are not just evident in Trump Administration documents, but shared by US society as a whole. This spring, supply of US semiconductors to the Chinese communications equipment maker ZTE was halted due to the company’s illegal exports to Iran and North Korea. It is rumored that, due to the stop in supply of US parts, ZTE was no longer able to manufacture its own products and went bankrupt. At that time, President Trump was aiming for a deal with North Korea and hinted that he might relax sanctions at the request of Xi Jinping. Concerning this, Congress and others were critical of the Trump administration.

The economist Paul Krugman was also critical, saying “[Trump is] a president using obviously fake national security arguments to hurt democratic allies, while ignoring very real national security concerns to help a hostile dictatorship.” (New York Times, May 28, 2018) Yet even Krugman, who has been repeatedly and fiercely critical of Trump, considers China a “hostile dictatorship” and clearly a “very real national security concern.” At present, for the Democrats and their supporters, the technological challenge from China (i.e. the unfair means used), is becoming a shared threat to the whole of the United States.

The United States’ current stance towards China has not arisen simply from the Trump administration, still less from President Trump’s own temporary assumptions. (Lately, there has been an inclination in the United States to cooperate with the EU and Japan to create a WTO rule framework regarding protection of intellectual property rights, technology transfer, and state support for industrial policy. In this too, we can see the direction of overall US national interest.)

Changes to the global system over the last twenty years

Ultimately, this view of China in the United States has arisen and been formed due to changes in China itself over the last twenty years or more. When the Cold War ended, China’s GDP (exchange rate adjusted) was around a quarter of Japan’s, but by 2010 it had overtaken Japan. In around 1990, China’s official military spending too was far less than Japan’s, but now it is more than three times as much. China has improved its naval and air capacity, and since the beginning of the 2010s has not hesitated to take a confrontational stance towards Japan in the East China Sea, while also moving forwards with the establishment of advantageous “facts on the ground” such as the building of artificial islands in the South China Sea.

The United States has continued to reevaluate its understanding of China in the face of a nation that does not hesitate to wield power overseas. A typical example of this is the National Security Strategy mentioned above.

According to the strategy document: “For decades, U.S. policy was rooted in the belief that support for China’s rise and for its integration into the post-war international order would liberalize China. Contrary to our hopes, China expanded its power at the expense of the sovereignty of others. China gathers and exploits data on an unrivaled scale and spreads features of its authoritarian system, including corruption and the use of surveillance.” Moreover, Kurt M. Campbell and others have demonstrated a similar perception when implementing South Asia policy during Democrat administrations.

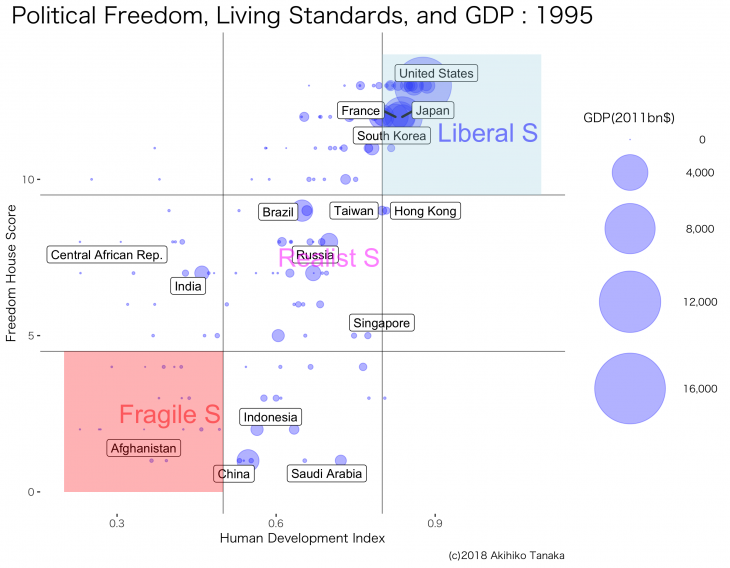

For some time, I have asserted that countries’ behavior within the global system becomes generally easier to understand when they are categorized according to freedom of political system and level of living standards. Countries with high living standards and high levels of political freedom (the “free world”) are accorded a “peace of democratic nations” and free movement of people becomes possible based on economic interdependence. Meanwhile, I have posited the possibility of conflict among other countries (the “realist world” and the “fragile world”) themselves or with the countries of the free world. Based on these ideas, I have made a graph that plots political freedom and living standards in nations of the world against two axes. I used indicators for Freedom House (an American NGO that monitors freedom and democracy) for the freedom axis and the United Nations Development Program human development indicator for the living standards.

Figure 1: 1995

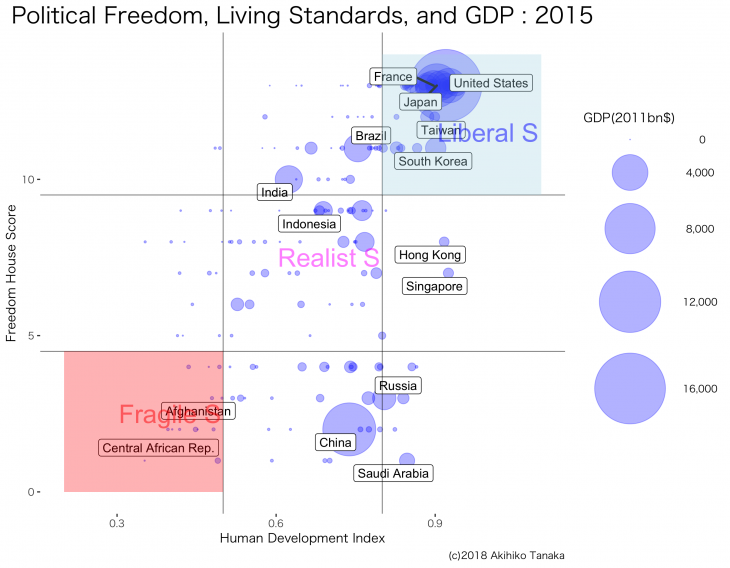

Figure 2: 2015

Figure 1 (1995) shows both political freedom and living standards, with the size of the circle representing a nation’s GDP. Countries that have high political freedom and high living standards are located at the graph’s top right. The United States, Japan and other countries are here. Looking at the overall distribution, the higher living standards are where the more political freedom exists, and we can also see a tendency for economies to be larger. In other words, just after the end of the Cold War in 1995 we could observe a trend in which democratization progresses as living standards rise (the so-called modernization theory), Just prior to this, the once authoritarian states of South Korea and Taiwan had achieved democratization as their economies grew; developments that served as evidence to back up this trend. Then, China was still poor and located at the bottom left of the graph. Post breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia was seeing democratization and had a relatively high degree of political freedom.

Figure 2, however, shows the distribution in 2015. We can see how India and Indonesia have moved towards the top right of the graph. At the same time, China did not see any increase in political freedom at all, yet living standards went up as the economic greatly increased in size. Russia, meanwhile, has seen a gradual decrease in political freedom as it moves towards the bottom right of the graph, but it has also recovered in terms of economic size. In other words, while in figure 1 many countries tended to move towards the top right of the graph, in figure 2 there is a striking move towards the bottom right as well as the shift towards the top right.

Just as these changes to the world system were gradually becoming apparent, General Secretary Xi Jinping made the following statement at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China.

This is what socialism with Chinese characteristics entering a new era means… It means that the path, the theory, the system, and the culture of socialism with Chinese characteristics have kept developing, blazing a new trial for other developing countries to achieve modernization. It offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence; and it offers Chinese wisdom and a Chinese approach to solving the problems facing mankind.

In short, China has demonstrated that there is a potential path towards the bottom right of the figure 2 graph; namely, a development model for developing countries. But are Xi Jinping and the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party really serious? Considering the Chinese Communist Party system of rule and the nature of its decision making, it is inconceivable that the language that appears in the General Secretary’s statement was included only at the whim of the leaders.

From a chronological perspective, the US National Security Strategy announced exactly two months after this statement acknowledged that the US policy to date (i.e. that supporting the rise of China would lead to liberalization in China) had been mistaken. If it is true that current US-China relations are really entering a new Cold War, Xi Jinping’s statement itself may have been the declaration of a new Cold War’s start.

The start of a new Cold War and Japan’s position

Of course, it is possible that US-China relations will not face any particularly intense conflict, still less military confrontation. The US National Security Strategy also states that, while the United States is in competition with revisionist states such as China and Russia, this will not immediately lead to conflict or military confrontation. From approximately spring 2018, China has also worked extremely hard to moderate the tone of its external hardline stance. On occasions, China has also made some fairly bold compromises in its trade war with the United States, so it may respond to the US issues of protecting intellectual property rights and technology transfer.

Yet, as long as the Chinese Communist Party tries to maintain its current political system, a “new Cold War” will continue under the surface. When the leaders of a country with as huge an economy and as influential as China offer a development model to replace liberal democracy, we can only say that the world has entered a kind of ideological conflict. After the end of the Cold War, for a while challengers to liberal democracy in the form of political ideologies disappeared. In terms of its economic possibilities, Islamic fundamentalism did not really possess a development program that could go up against liberal democracy. But that is not the case for the development model proposed by China… because it has already shown results.

Yet, because China’s domestic model is based on a hardline authoritarian system that denies freedom to its people, and because of the huge size of China’s economic system and military power, it can be a threat to liberal democratic nations both in terms of external security and internal politics. Should domestic forces that support Chinese-style ideology spring up, there is a danger that something like a “domestic cold war” might occur, as it has in the past.

If this “new Cold War” intensifies, it will not be possible for liberal democratic countries like Japan to see it as someone else’s problem. Japan has no choice but to make its position clear. On the other hand, depending on shifts in China’s stance going forward, this new Cold War may appear to have slipped under the surface. Nevertheless, the relationship with China is unlikely to continue as it has in the past. When it comes to security-related high-tech fields in particular, it will be necessary to take careful action to ensure that important technology is not transferred. Together with the United States and countries of Europe, Japan needs to make the necessary demands on China in the areas of protecting intellectual property rights, the issue of technology transfer, and data management.

In any case, it is inconceivable that China would give up on its dream of further advancing its economy. The ZTE incident may have actually strengthened China’s resolve to bring high technology within China. This new Cold War will continue both as a battle between ideological systems and as a contest over advanced industrial technology. As a key liberal democratic nation, Japan needs to ready itself to make sure it does not lose the contest over science and technology.

Nevertheless, even if the new Cold war is a “cool” battle we must prevent it from becoming a “hot” one. From the Japanese perspective, we need to strengthen the Japan-US alliance and maintain our deterrence capability, as well as create a space for peaceful coexistence with China. If we decide as a basic principle that the recently discussed cooperation between Japanese and Chinese companies in the Indo-Pacific will contribute to the development of emerging nations in that region, there is no reason for Japan to hesitate with our cooperation. Regarding projects in third countries, as long as irresponsible external loans are not made and sustainable development that considers the environment and human rights happens, this will not be seen by emerging nations as an exported

. Also, if such joint projects influence the actions of Chinese companies, it may contribute to a change in the Chinese model itself.

Even within China there are those raising the alarm bell regarding the “arrogant” external stance expressed last year in Xi Jinping’s statement, and who do not consider strengthening of internal suppression a good thing. Although Japan cannot base its China policies and its security policies on the premise that China will move towards liberalization, we must not forget that there are people in China who seek liberalization. There is no need to think that the path to liberalization in China is completely barred.

Translated from “Tokushu—Beichu Gekitotsu to Nihon no Kiki: Chugoku taito de Henyosuru Kokusai sisutemu—Boekisenso kara ‘Atarashii Reisen’ e (Special feature: The US-China clash and the crisis for Japan: Changes to the international system due to the rise of China—From trade wars to a “new Cold War”),” Chuokoron, November 2018, pp. 26–37. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [November 2018]

Keywords

- Future Design

- international system

- new Cold War

- US-China

- trade friction

- President Trump

- Made in China 2025

- intellectual property rights

- high-tech industries

- US National Security Strategy

- Chinese model

- ZTE

- Iran

- North Korea

- Xi Jinping

- Communist Party of China

- hostile dictatorship

- hardline authoritarian system

- Japan-US alliance