China’s Forty years of Reform and Opening: Japan should discuss China’s originality beyond the argument that it is a country of a completely different nature

Key Points

- The argument that China is a country of a completely different nature is rising in the United States, and the US has changed its policy toward China

- Coexisting with dispersive private economy and authoritarian systems

- Japan should place priority on pursuing mutual economic benefits

Prof. Kajitani Kai

Amid the growing mood of celebrating the 40th anniversary of China’s reform and opening within the country, there is pessimism that the rivalry between the United States and China could become increasingly serious and prolonged beyond being solely a trade issue. This pessimism is based on a speech delivered by US Vice President Mike Pence at a conservative think tank on October 4.

The reason why the speech shocked many people was not only that it comprehensively included the Trump administration’s tough stance against China on political, military and human rights issues as well as trade issues, but also that his argument was totally caught up in the idea that China is a state of a completely different nature.

After the launch of China’s reform and opening, previous US administrations promoted an engagement policy based on the conviction that Chinese economic development would help foster the middle class, which would lead to establishing the rule of law and democratization. However, pessimism over China’s efforts to change its political and economic systems began to arise in the latter half of the Democrats’ Obama administration.

Xi Jinping declared the lifting of presidential term limits at the National People’s Congress in March 2018, which made it clear that his administration would last for a long time. This appears to have played a critical role in the US shifting its China policy toward deterrence. Undoubtedly, the rise of the argument that China is a state of a completely different nature constitutes the core of the shift in the US policy toward China.

The US policy toward China seems to have achieved an about-face from engagement to deterrence. But these two stances have something strange in common in terms of a certain point of view. That is, it is the dichotomous point of view that the political and economic systems that currently exist in the West are the sole universal ones and that other systems are recognized as long as they converge toward them, but that “systems of a different nature” must not exist.

In this context, Japanese China researchers have raised the question of whether or not the Chinese model will converge to the Western “universal” model in a softer manner in a way that will enable them to avoid the dichotomous point of view.

According to Ochanomizu University Professor Emeritus Kishimoto Mio, who specializes in Chinese history during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the postwar paradigm of Chinese studies is roughly classified into the type theory focusing on the differences between Chinese society and Western and Japanese societies based on prewar critical thinking, and the development step theory in which each period of Chinese history is positioned within the development steps modeled on the West under the influence of Marxist historical studies.

This type theory is not always consistent with the American argument that China is a country of a completely different nature because some type theory-based arguments about China note the aspect that while the Chinese economy lacks systematic infrastructures and involves risks and instability and “freedom like scattered sands” produced by them, it has a degree of originality that cannot be grasped by the unilinear development step theory, and they look to evaluate its significance in a positive light.

The late Kato Hiroyuki, economist and former professor at Kobe University, attributed the source of the dynamism of Chinese capitalism, which is full of uncertainty, to the ambiguity of a system that supports a market economy, and undertook active research. In An Introduction to Chinese Economics, he paid attention to the ethical discipline of Bao, which was set forth by sociologist Kashiwa Sukekata during and after World War II, as an original system supporting the Chinese economy.

Bao is a general term for a subcontract and means “hundred-percent subcontracting,” or the fulfillment of a certain service to a third person. In China after the reform and opening, the production subcontracting system between farmers and local governments or the financial subcontracting system between superior and subordinate governments made a significant contribution to the advancement of the Chinese economy in later years.

Kato positively evaluated ambiguous systems, especially Bao, for their flexibility and unintended strength against the risks caused by the change in the global economy. Kato’s argument emphasizing the originality of the economic system in modern China was the developed version of the tradition of the type theory-based Chinese argument that had been taken over to Japanese China studies since before World War II.

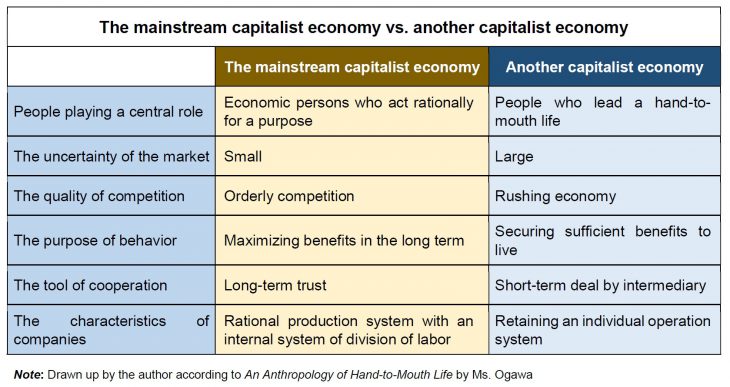

It is not limited solely to China researchers who argue against the view that the capitalist economy will converge to the universal Western model in Japan. In An Anthropology of Hand-to-Mouth Life, Ogawa Sayaka, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Ritsumeikan University, notes that urban people who lead a hand-to-mouth life are a third type, who are neither economic persons who act rationally for a purpose as an ideal type supporting modern capitalist society nor premodern persons shackled by traditions and customs living in farming villages left behind by modernization, and describes “another capitalist economy” created by those people. (Refer to the chart below.)

The books by Ogawa, whose research field is Africa, and Kato, whose research field is China, have a lot that resonates with each other beyond the differences in geographical area and field. This is because their books take the approach of interpreting an orientation toward type theory; that is, the irregular phenomena observed in the African and Chinese economies, not as transitional phenomena in the yet-to-be-developed stage of the market but as something that constitutes another capitalist economy that differs from the mainstream capitalist economy in many ways in terms of types.

You must not forget the fact that another capitalist economy is highly compatible with authoritarian political systems. One of the reasons for this is that in short, economic activities based on short-term and unstable business relationships prevent intermediate groups that are independent from political powers, such as labor unions and industrial groups, from being organized. The absence of such groups creates a kind of freedom, including the vigorous entry of small businesses into the market economy, which in turn weakens autonomy that is strong enough to bounce back against political intervention in the market.

The traditional Chinese business custom of resolving the prisoner’s dilemma-like mutual distrust inherent in short-term deals by influential intermediaries’ mediations, not by regulation by law and trial, is another reason for the compatibility with authoritarian political systems. In traditional Chinese society, influential intermediaries enjoying great reliability and original information networks always maintained close relationships with official powers and supported the economic order.

The system of facilitating efficient management by the official powers by mediations and controls of small businesses by influential intermediaries is also taken over for intermediary systems through the Internet in modern China, such as the Alibaba Group and Tencent. But it can be considered that the fact that the method of avoiding deal-related problems by intermediaries without depending on legal systems that are developed at a high level shows that public confidence in legal systems in society remains low, and the rule of law is hard to establish.

On the whole, the coexistence between highly dispersive and free private economic activities that were created by outmaneuvering the rules established by the official powers and authoritarian political systems out of the reach of the rule of law in a subtly harmonious way is the greatest feature of the current Chinese political and economic systems. This combination between the two will remain firmly unshakable.

Japanese China studies have an accumulation of the traditional approach of looking at China as another type on the basis of neither the step theory nor the argument that China is a country of a completely different nature based on the assumption that the Western model is the one and only goal. We Japanese, who took over the tradition, should look to the approach of pursuing mutual economic benefits through multilateral frameworks, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), by neither aligning our position with that of the current authoritarian Chinese administration nor following the dichotomous American view of China.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 13 December 2018 under the title, “Chugoku Kaikakukaiho no 40 nen (2): ‘Ishitsuron’ koe Dokujisei giron wo (China’s Forty Years of Reform and Opening (2): Japan should discuss China’s originality beyond the argument that it is a country of a completely different nature).” The Nikkei, 13 December 2018. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- China’s reform and opening

- Mike Pence

- engagement policy

- Xi Jinping

- National People’s Congress

- type theory

- another capitalist economy

- intermediary system

- rule of law

- WTO

- RCEP