China’s Forty Years of Reform and Opening: Governance Model Lacking Consistency

Key Points

- The search for specific reform methods after Deng Xiaoping

- A top-down approach cannot sustain one-party rule

- Issues in the East China Sea reflect China’s views of the public order

Prof. Kamo Tomoki

Roughly forty years have passed since the Communist Party of China (CPC) adopted the policy of reform and opening up. During this period, the international community has wavered between two different perspectives towards China. The first is based on expectations, while the second is grounded in concern.

The international community has consistently placed hope in the Chinese economy, which has assumed the responsibility of leading global economic growth. With its national strength supported by economic growth, China has reached a position where it affects the distribution of power in the community of nations. It has gradually taken an active role in the reform of global governance and displayed a desire to lead those reforms. Concern lies ahead of those developments.

The type of global governance pictured by China remains unclear. The global community observes China’s actions in the airspace and waters such as the East China Sea and South China Sea, which appear to be attempts to change the status quo by force, as problems that reflect the country’s latent views of the public order.

The global community is questioning where China will go from here. Clues to the answer of that question lie in the course taken by China over the last forty years.

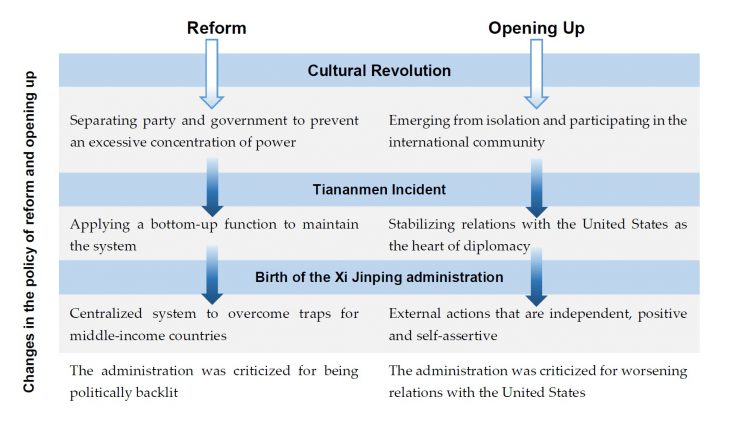

We can divide the Chinese policy of reform and opening up in half. Reform means initiatives on domestic matters in China, while opening up means initiatives for the international community. The last forty years have served as a course of trial and error for China.

The policy of reform calls into question the CPC’s style of governance. In particular, one style of governance was a rehash of the Cultural Revolution, in other words, political reform to prevent a cult of personality built around political leaders and abuse of power. The other style was economic reform for designing the systems required for the modernization of China’s economy.

Under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s, the CPC set its method for guiding China and society on the table for discussion, introduced term limits for positions including the president, and proposed a policy of separating party and government that divided the functions of the CPC and the government. Furthermore, the CPC started to design systems in charge of expressing, integrating and coordinating interests in a bid to adapt China to the multipolarization of social benefits and values associated with reforms in a planned economy. However, the CPC abandoned those initiatives following the Tiananmen Incident in June 1989, because the series of reforms was suspected as a main cause.

Under Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, the Chinese administration became devoted to economic reforms from the 1990s. The CPC searched for a way to introduce public hearings, censure and other systems for learning about sources of dissatisfaction and cracks in Chinese society when it became diversified with the development of a market economy and less stable due to increased acts of protest and similar activities attributable to gaps, even though the Party completely rejected political liberalization. Those efforts are one of the primary factors behind the continuation of the CPC’s rule after the Tiananmen Incident.

However, the style of governance chosen by the Xi Jinping administration is oriented against the previous direction. China must avoid traps for middle-income countries to simultaneously achieve a stable society and economic growth. Therefore, the present administration chose to enhance the CPC’s guidance based on the view that strong leadership is indispensable.

The administration concentrated power on Xi by abolishing the term limits for the president established in the 1980s, among other steps. At the same time, the administration strengthened its management of society. Furthermore, the administration publicized China’s position as a strong nation domestically and overseas. Currently, the administration is trying to boost China’s cohesive power more than ever with the help of nationalism. However, this is receiving criticism domestically.

The policy of opening up answered the question of how China should face the global community. The CPC shifted its understanding of the international environment from wars and revolutions in the days of Mao Zedong to peace and development in the 1980s. This shift to the view that large-scale wars could be avoided followed the strategy of formulating the diplomatic conditions necessary for modernizing the economy.

Discussions have continued over the content of the strategy. How should China evaluate the existing world order led by the United States? How should China involve itself in that order as a member of the global community? What kind of responsibility should China bear and to what extent? Points of concern changed as China’s strength rose, diplomatic choices increased and social interests diversified.

The CPC has succeeded in securing the stable international conditions needed for economic development by firmly maintaining a rapprochement with the United States, which is known in Chinese as hiding claws and saving power, since the 1990s. However, the CPC has not referred to this expression on any formal occasion since the inauguration of the Xi administration.

With a stronger sense of national greatness, the Chinese administration chose external actions that were more independent, positive and self-assertive. The proposal of a community of shared future for mankind and the advancement of the Belt and Road Initiative for a wide-area economic bloc are examples of such an approach. However, the steering of diplomacy by the Xi administration is receiving criticism, because the relationship with the United States at the very heart of China’s diplomacy has destabilized since last spring, with trade friction as a turning point.

The Xi administration is publicizing the China solution as the fruit of the efforts made by the country over the past forty years and as a model for developing countries to simultaneously stabilize their society and develop their economy. The administration is saying that top-down centralized governance guarantees the concurrent achievement of stability and growth. The assertion that the CPC is infallible and China’s leadership in global governance reforms is valid is incorporated in this argument. However, it does not accurately explain actual conditions. In the first place, no consistent model has existed for the CPC. The Party has taken a heuristic approach.

China was able to achieve stability and growth because bottom-up mechanisms introduced by the CPC functioned well to maintain control, as if out of necessity, such as public hearings and censure systems, instead of top-down centralized governance.

Does a China solution exist? It is obvious that China’s search for a style of governance will continue.

Japan has deeply involved itself in the course that China has taken over the last forty years. Japan has provided economic assistance to China since 1979 in a variety of forms, including Official Development Assistance (ODA). The expectation that welcoming isolated China into the international community and encouraging the country to modernize will contribute to peace and prosperity in the world was the backdrop of this policy. However, Japan feels that the approach invited tension into the East China Sea.

In 2008, Japan and China announced cooperation in the East China Sea based on a shared view to turn the area into a sea of peace, cooperation and friendship, which is known as the 2008 Agreement. However, Chinese public vessels entered Japan’s territorial waters around the Senkaku Islands after the agreement in December 2008. Relations between the two countries have been tense ever since.

China chose to improve its relations with Japan last fall, even though the state of tension in the East China Sea remains unchanged. As far as published materials indicate, Japan has repeatedly reminded China of the existence of the 2008 agreement and China has not denied its existence. However, it is difficult to be optimistic about the path of this agreement. The restoration of order in the East China Sea will be important for judging how China views the world order.

Inspirationally, China summarized the last forty years under the policy of reform and opening up as a period in which the country has come to play a central role in the global community. China says that it will present a Chinese model for solving the issues faced by humanity. Going further, I think China will declare that it has started to follow a path beyond the policy of reform and opening up.

However, the CPC is still searching for a style of governance. China remains under the policy of reform and opening up, which it has maintained for forty years, which means that China has not yet been able to fully picture a style of global governance. There is still room for the global community to guide China within the existing world order, while working to improve standards associated with global governance.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 12 December 2018 under the title, “Chugoku Kaikakukaiho no 40 nen (1): Ikkansei kaita ‘Tochi Moderu’ (China’s Forty Years of Reform and Opening (1): Governance Model Lacking Consistency).” The Nikkei, 12 December 2018. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

-

- Deng Xiaoping

- policy of reform and opening

- global governance

- South China Sea

- Cultural Revolution

- Tiananmen Incident

- Xi Jinping

- sense of national greatness

- Belt and Road Initiative

- trade friction

- China solution

- top-down centralized governance

- ODA

- East China Sea

- Sea of Peace, Cooperation and Friendship

- Chinese public vessels