DON’T FEAR HOLLOWING OUT–TRANSFORMING INTO AN INVESTMENT NATION Will SAVE JAPAN

From GDP to GNI

Hayashi Yoshimasa

In Japan, economic policy discussions are no longer capable of providing us with dreams. The country is full of gloomy storylines: population decline, ongoing deflation, social welfare difficulties, the incessantly strong yen, and stalled growth. People are also not interested in pursuing the subject of change as they are caught in the grips of past success stories. Things are decided in a trickling way, as if people are thinking that, “at least for now this is all we have to do.”

Japan is currently facing many thorny problems, ranging from short-term challenges such as how to recover from the earthquake and how to deal with the energy problem to longer-term difficulties such as the deteriorating fiscal situation, low economic growth and the aging population paired with a declining birthrate. Though Japan is certainly in a phase where optimism is difficult, policymakers must establish a forward-looking vision, even under these circumstances. We should find solutions for expanding the overall pie even amid a climate in which we are inclined to grieve, without being engrossed in maintaining the status quo. For that purpose, Japan needs comprehensive growth strategies in a true sense, and not limited to tactics such as infrastructure export and “cool Japan.”

As one approach to this end, we would like to suggest making gross national income (GNI) an indicator replacing gross domestic product (GDP).

GNI is similar to the classic gross national product (GNP) and the concept of viewing GNP from a distribution angle. The former Economic Planning Agency of Japan (current Cabinet Office) had been using GDP in place of GNP since 1993, and the National Accounts of Japan have been using GNI instead of GNP since 2000. GNI is an indicator obtained by adding the net receipt of interest and dividend payments from overseas, and can be very simply expressed by the following formula.

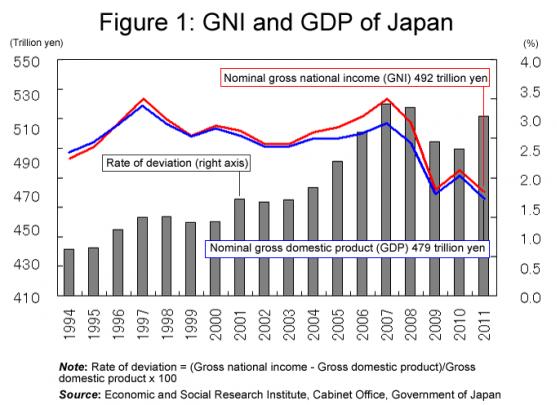

While Japan’s GDP has been growing at a sluggish pace, the balance of income has been increasing steadily, and GNI is around 3% larger than GDP (Note) (Figure 1). Only a few examples with such a large difference between GNI and GDP in developed nations exist in the West, proving there are active overseas investments by Japan and overseas activities of Japanese companies.

We therefore would like to outline comprehensive strategies for a bright future for Japan by establishing maximization of GNI as a major objective of economic policymaking and linking other policies with this.

The GNI Study Group has held nine meetings between October and December 2011 to hear opinions of experts and hold discussions. The rest of this paper is still something like an interim report, but we would like to disclose this information here to ask more people to participate in our discussions.

Aiming to maximize the wealth of the people

Though this topic has already been subject to ample discussion, given the low birthrate and longevity, the domestic market is limited for the Japanese economy to keep growing and developing. The Japanese market accounts for only 8% of that of the world. Though we often hear that Japan’s export dependency is only 15% of the GDP, there is simply no justification for discussions that do not take overseas markets into account, given that Japan depends on other countries for so much of its food and energy.

Fortunately, the Asia-Pacific region where Japan is located has great potential. In the present-day circumstances, Japanese people and companies need to take a giant leap forward overseas.

We therefore would like to establish “maximization of economic activities carried out by the Japanese people and companies throughout the world” as an objective by changing the criterion for economic policies from GDP to GNI. While GDP is the value-creation in Japan, GNI is the value creation by Japanese people throughout the world. Japan is the world’s largest credit country, and the balance of income is currently about 3% of the GDP and remains solid.

On the other hand, the balance of trade has been gradually decreasing since the second half of the 2000s. These two balances reversed in fiscal 2005, and since then the income surplus is surpassing the trade surplus. Speaking based on the stage theory of the balance of payments, Japan is highly likely to have shifted from an immature credit country to a mature one in around 2005. In other words, Japan today is considered to be in a process of transforming from a trade nation to an investment nation.

If Japan that once aimed to become a GDP power aspires to become a GNI power, the following three steps will be important.

1.Japanese people and companies flourish overseas

2.The achievements of these activities are returned to Japan

3.This leads to the creation of jobs in Japan

From here, we will discuss necessary challenges for each step.

First step: Becoming an investment power

When considering that Japan should aim to become an investment nation rather than a trade nation, the current yen appreciation is in fact far from being a calamity and is instead a very rare bargain opportunity. Since active foreign investment means buying foreign currencies and selling yen, this at the same time becomes a countermeasure against the strong yen. Many Japanese companies have already set out to acquire foreign companies, and this is a sensible move.

Leading Japanese pharmaceutical companies have also been rearranging their production bases to cope with the strong yen. Overseas advancement by Japanese companies since the Plaza Accord has been contributing to development of local economies by creating a powerful industry accumulation in many parts of East Asia and strengthening the international competitiveness of Japanese companies. Yet a significant number of voices from among Japanese companies say we can no longer put up with the current exchange rate in the 70-yen level against the dollar.

We believe that Japanese companies should be even more aggressive in going overseas without fearing hollowing out. For starters, the concern about hollowing out is an idea from the “GDP maximization” era for preserving as many jobs as possible in Japan. The “GNI maximization” strategy, conversely, aims at gaining as much return as possible, collectively supported by Japanese companies expanding their activities in Japan and overseas as a unit and establishing new operating bases overseas. Companies that promote globalization are never reducing their workforce in Japan. Japanese companies should take on new domains without sinking into a zero-sum mindset.

Japan has many companies that are complacent regarding low earnings, despite high capability with the world’s most advanced technologies. The inward-focused management climate and slow decision-making process have in many cases proved harmful. It is therefore necessary to liberate Japanese companies from their home bias and build a strong constitution to fight by bringing Japan brands to the fore.

In terms of profiting overseas, Japan benefits from favorable conditions since it is situated in the fast-growing Asia-Pacific region. In the current Japanese economy, trade with Asian countries accounts for more than half of total trade, yet investment destinations are centered on Europe and the United States. The overall image is of making money in Asia and investing in Europe and the United States, but performance should be even better if Japan both makes money and invests in Asia.

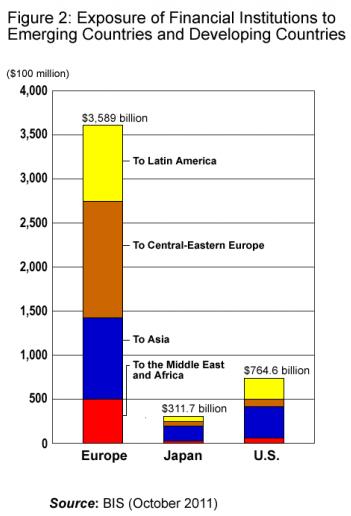

A particularly vital area is to prevent the financial crisis from spilling over into Asia, given the expanding debt crisis in Europe. European financial institutions have wide exposure (amount of credit) in Asia (Figure 2). Japanese financial institutions are therefore required to actively advance into Asia to contribute to the region’s stability, so that the declining strength of European financial institutions will not trigger a credit crunch in the future.

The Chiang Mai Initiative has already allowed Japan, China, South Korea and the ASEAN nations to mutually accommodate their foreign exchange reserves. Creating stable financial markets in Asia will in the long run also be beneficial for Japanese investors.

Since 2003, ASEAN Plus Three (APT) has already been taking an approach called the Asian Bond Markets Initiative (ABMI) for the purpose of utilizing savings in Asia as investments in Asia. Though investments are now made mainly in government bonds, going forward, the corporate bond and securities markets should be developed to promote investments, with the aim of incorporating high growth in Asia.

Trade liberalization in the Asia-Pacific region is also an important issue. Japan should hold a leadership position in creating the economic zone in the region, and particularly from the standpoint of increasing GNI, liberalization of investments and services is an important task. We wish to point out that while Japan has currently concluded only 27 investment agreements, this is far behind other countries such as Germany (137), China (127) and South Korea (90).

To support Japanese companies in policy matters, government agencies such as the Japan Finance Corporation (JBIC), Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) and Innovation Network Corporation of Japan are taking approaches to promote foreign investment through the private sector, using the government’s Financial Stabilization Fund. Though these organizations were the targets of administrative reform and privatization in the past based on the concept of leaving things that can be done by the private sector to the private sector, seen from a different angle they can be regarded as the Japanese-version of a sovereign wealth fund (SWF). Many of the emerging countries that have been making remarkable progress are managing their SWFs and government agencies for the sake of national capitalism. The hope is that Japan, too, will use these government agencies strategically and build a collaborative framework between the public and private sector.

In that regard, it is also important to send people as well as companies overseas. Though people are inclined to look inward after the earthquake, activating the movement of people both inbound and outbound across borders in the form of not only business but also tourism and overseas education is also important for maximizing the GNI.

Second step: Returning overseas wealth to Japan

If maximizing the GNI is set as the objective of economic policies, it will be important to return wealth earned overseas by Japanese companies to Japan.

This process will not pose a problem so long as profits Japanese companies make overseas are brought back to Japan and recorded as income, and resulting corporate tax revenues flow into state coffers. However, in some cases, Japanese companies may avoid exchange losses that arise from converting foreign currencies earned overseas into yen. Important here is the way in which the tax system is arranged to make it easy for these companies to bring their foreign income back to Japan.

For example, the U.S. Homeland Investment Act takes an approach of giving preferential tax treatment for remittance of profits, dividends, etc. by U.S. companies overseas, though a temporary statute limits the use of the proceeds. Japan, in contrast, introduced a system in 2009 to make dividends from overseas subsidiaries tax-free, in principle, without limiting use. Owing to this system, dividends returned to Japan have remained stable, even though earnings of Japanese companies have been declining in the decelerating global economy following the Lehman Brothers collapse.

Not only this, but factors that impede the flowing back of funds from overseas also need to be eliminated in ways such as asking interested states to improve their regulations on remittance and systems related to compensation for technology licensing, and enhancing the network of tax conventions. The aforementioned conclusion of an investment agreement is also important in this regard.

The next challenge is money flow from the corporate sector to the household sector. It used to be taken for granted that corporate earnings were paid out at some stage in the form of dividends and wages and flowed back to the household sector, but since around the start of the twenty-first century, the persisting situation sees the corporate sector earning high profits but not returning them to the household sector, and consumer spending has not received the resultant boost. This is also a noticeable tendency in the recent U.S. economy and has become one of the factors underlying the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations, as strong companies and weak households live side by side.

Particularly income that companies earn overseas tends to avoid heading to the source of dividends and employment. It would be more beneficial to the overall economy if companies increased employment and money ran through the household sector, and this would prolong favorable conditions. We would like to emphasize that staying alert on not only the supply side of the economy but also the demand side is ultimately a shortcut to creating total optimization.

We also should think about a route for the household sector to directly reap the rewards of global economic development. The most effective way is the growth of global companies penetrating the household sector through the wealth effect. As a tool, we suggest reflecting growth in Asia on the performance of pensions by using a Japanese version of the 401k. We do not need anti-business government or the business community’s government, but rather a pro-business government that will maintain healthy relations with the business community.

Third step: Increasing employment in Japan

Finally, it is necessary to increase employment in Japan based on the positive outcomes of economic development in Japan and overseas.

As mentioned earlier, if we think about economic policies with the GNI at the core, the overseas transfer of companies is certainly not unfavorable. There will naturally be concerned voices, warning that jobs will be lost in Japan, but a study by Professor Todo Yasuyuki at the University of Tokyo shows that companies that have moved their production bases overseas are actually increasing jobs. In fact, Komatsu, which enjoys a commanding position in construction machinery, has established research facilities on a vacant site of its production base in Komatsu City, the company’s birthplace. The contents of jobs here are different from before, but new jobs have been created in the local community.

What is important is for Japanese companies to maintain growth and prosperity by promoting globalization. We believe it is possible through globalization to create new jobs by unlocking the high potential of “sleeping dragon companies” buried in Japan, to enable them to flourish globally. Japan should aim for positive feedback in which Japanese companies bolster their strength by taking in the growth potential of Asian countries with the GNI strategy and have leeway to make new investments.

At the same time, an effort to create jobs in new areas is also essential. Speaking of new areas, the employed population is increasing in the medical and nursing care sectors in Japan. Four million people are expected to be newly employed in these sectors over the new two decades.

Yet this will not be realized simply by increasing the welfare budget. In Japan, with the aging population with declining birthrate, an ideal model is that self-help comes first, followed by mutual assistance, and then public help comes last. To leave Japan’s outstanding social capital (community bonds) for the next generation, we need wisdom to identify ideal forms of social welfare.

In the medical and nursing care sectors, it seems that opportunity actually exists beyond public health insurance. There is said to be no intermediate level between economy and first class in the current medical and nursing care services in Japan. Great demand could be developed by offering business class services to the group with a certain level of income.

For instance, expansion of the supply of readily accessible housekeeping services for seniors living alone could lead to a situation in which supply creates its own demand. Development of the supply of services should grow into businesses convenient even for ordinary citizens.

Constructing the comprehensive policy system

Economic policies are currently discussed individually and in a trickling way, and overall strategies are lacking. We therefore propose constructing a new policy system using the GNI as the core concept.

With respect to the tax system, the government should take necessary measures and eliminate obstructions to promote tax breaks for investments; which encourages companies and individuals to advance and invest overseas and return funds to Japan. Based on this, in order to maintain the middle class in Japan it is important to shift to a system focusing more on assets (stock) than on income (flow) when making important redistribution.

Regarding social security policy, measures should be promoted to improve services outside the public insurance system on the premise that public security will be improved through the consumption tax. This will help secure workplaces where the middle class can work at ease and to the foreign wealthy class promote the use of finely tuned differentiated services unique to Japan.

In trade policy, economic partnership agreements that focus more on investment and intellectual property, rather than on goods and services, should be promoted. At the same time, the government should promote conclusion of tax treaties and social security agreements with other countries.

To secure stable energy resources, it is necessary to adopt policies targeting the upstream, such as joint development and the preservation of Japan’s interests overseas. The government should also actively promote development of infrastructure in Asia as a whole, such as joint pipelines in Asia and the channeling of the Kra Isthmus (the narrow land bridge connecting the Malay Peninsula to mainland Asia).

Finally, we wish to emphasize the importance of education to support the GNI strategy of Japan. In this regard, issues are extensive, including the English education system in school and the cultivation of human resources who support the global operation of companies. For example, thinking about the top six universities in Asia, Peking University, Tsinghua University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, the University of Hong Kong and the National University of Singapore are probably safe candidates, but under the current circumstances even the University of Tokyo is competing with Seoul National University and National Taiwan University for sixth place by a narrow margin.

In any case, in considering Japan’s economic policies with the GNI at the core, it becomes clear that Japan has a lot to do. At the same time, however, we can feel hopeful and have dreams.

We look forward to receiving creative and constructive opinions and criticism from the readers.

Note: Nominal GNI is 492 trillion yen, and nominal GDP is 479 trillion yen (calendar year 2010). In real terms, trading gains need to be taken into account.

Translated from “Kudo-ka wo osoreruna – Toshi-rikkoku eno dappi ga nihon wo sukuu (Don’t Fear Hollowing Out – Transforming into an investment nation will save Japan),” Chuokoron, February 2012, pp. 192-200. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [February 2012]