Focus of Japan-U.S. Economic Dialogue (II) Japan as a Bridge Between the U.S. and East Asia: Perspective on a framework for discussion which includes China

Key Points

- The economic-security nexus in U.S.-Japan relations is irrational.

- The TPP should be ratified in the other 11 member countries, and the door left open for U.S. participation.

- Japan should lead RCEP and Japan-China-South Korea FTA negotiations.

Mr. Tanaka Hitoshi

U.S. Vice President Mike Pense will visit Japan to work with Japan’s Deputy Prime Minister Aso Taro on a new Japan-U.S. Economic Dialogue based on consensus reached in the Japan-U.S. summit meeting.

In the 1980s, at the time of severe economic frictions between the U.S. and Japan under President Reagan’s Republican administration, I conducted negotiations with the U.S. as a member of Japan’s Foreign Ministry. I would like to examine the implications (of the upcoming negotiations) for Japan’s foreign relations and economy, comparing the situation now with the situation then.

First, the U.S. trade deficit itself has expanded from 50 billion dollars in the early 1980s to 750 billion dollars in 2015 and yet Japan’s share of the U.S. trade deficit has decreased substantially. In the early 1980s, Japan accounted for more than 50% of the U.S. trade deficit, whereas in 2015 Japan’s share was down to 9%. Since the 2000s, the U.S. has notched up a large trade deficit with China in place of Japan, with China accounting for almost 50% of the U.S. trade deficit in 2015.

President Trump issued a Presidential Executive Order on March 31, ordering the Departments of Commerce and the United States Trade Representative to develop an omnibus trade deficit report within 90 days. From the 1980s to the 1990s, Japan was at the center of trade problems, but the biggest problem today is China.

The geopolitical background is also vastly different. In the 1980s, in response to extremely strong demands from the U.S. prompted by a large trade deficit and high unemployment, Japan signed the 1985 Plaza Accord, agreeing to appreciation of the yen against the dollar, the adoption of voluntary restraints on exports of cars, steel, machine tools and other goods to the U.S., and steps towards the liberation of its markets in many areas. It is, of course, true that Japan was under extremely strong pressure, with the U.S. invoking Section 301 of the US Trade Act to take retaliatory measures against Japan. However, Japan’s biggest motivation for its actions were security-related considerations.

Ronald Reagan rose to power at a time when the Cold War was at its peak due to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan and there were calls from the American people for a strong United States. President Reagan called for expansion of the U.S. military budget and also for US allies to play a stronger role. The Nakasone administration stressed the importance of making an appropriate contribution to U.S. world leadership as “a member of the Western camp,” and increased Official Development Assistance. At the same time, it was committed to market liberalization. Strong recognition of the need not ruin Japan-US relations through economic frictions also existed.

Japan still relies on the U.S. for security, and also harbors considerable security-related concerns chiefly in relation to China and North Korea. The importance of the Japan-US security relationship has by no means diminished since the Cold War era. However, Japan’s markets are now as open as those of other advanced countries and, in the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, consensus on market access in any remaining areas has also been reached.

Meanwhile, the U.S. economy is strong. According to a poll conducted by U.S. research agency the Pew Research Center from February to March, the assessment of the U.S. economy is the most positive it has been since the global financial crisis in 2008. It may be that Japan needs to play a stronger security role in its relationship with the United States, but the economic-security nexus is now illogical.

The current situation is vastly different from the economic frictions in the 1980s. That said, what implications will the new Japan-U.S. economic dialogue have? According to recent reports, the new economic dialogue will focus on three aspects; (1) macroeconomic cooperation, (2) economic partnerships, and (3) trade frameworks.

In terms of macroeconomic cooperation, the joint communique specifically mentions the three arrow approach – a combination of fiscal, monetary, and structural strategies. Ideally, both the Japanese and U.S. governments will deepen understanding and discussions about their respective macroeconomic within the broad framework of the three arrows. It cannot categorically be said that the U.S. does not see a weak yen as a problem but its approach to the value of the U.S. dollar has yet to be decided.

As for Japan-U.S. cooperation, there is huge potential for Japan and the U.S. to complement each other in areas such as energy, infrastructure, cyber security and space. Especially with regard to energy, Japan has started importing liquefied natural gas (LNG) produced from shale formations in the U.S., and the U.S will play an extremely important role in the energy security of Japan, which is currently overly reliant on the Middle East.

President Trump is also keen to invest in U.S. infrastructure, and there is much scope for cooperation with Japan’s private sector. In particular, plans for high-speed railways in key regions, such as California, Texas and Washington-New York, are already being drawn up, and Japan’s participation would be desirable.

Issues that will have a major impact on Japan’s future foreign policy are those related to US-Japan and regional economic frameworks. These have important implications that will determine not only the future of Japan-US relations but also the basis of Japan’s foreign policy.

The strategic implication of the TPP was that Japan cooperated with the U.S. to set out rules for a sophisticated capitalist economy-rules that are different from those of national capitalism. At the same time, Japan is working on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which involves 16 countries – Japan, China, the Republic of Korea, the 10 members of the Association of South‐East Asian Nations (ASEAN), India, Australia and New Zealand. Underlying this was perhaps the vision of linking the RCEP to a broader Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP).

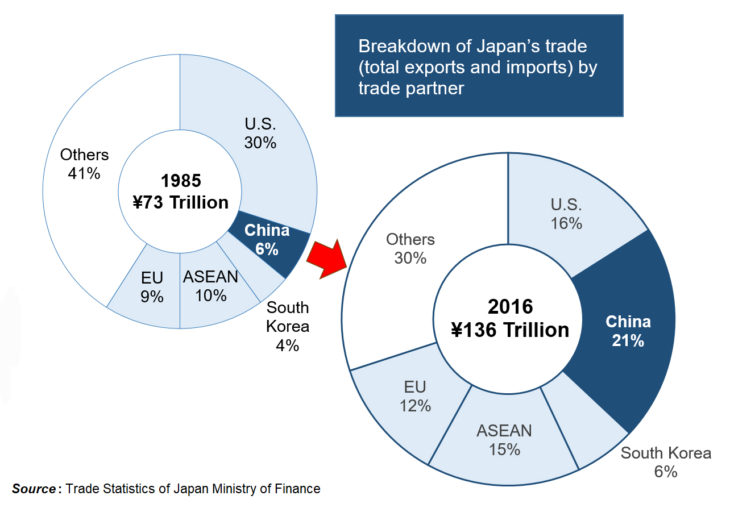

Expanding free trade agreements (FTAs) with foreign countries and strengthening economic cooperation is a policy that is critically important for Japan, faced as it is with population decline and shrinking domestic demand. Japan’s trade with the U.S. is less than it once was, and its trade with neighboring countries such as China and ASEAN members has increased dramatically (see the Figure). Promoting economic integration with neighboring countries including China is essential for Japan’s prosperity.

If Japan were to draw the U.S. into the regional economy via the TPP, it would surely safely advance its vision for the East Asia Region. U.S. withdrawal from the TPP casts a shadow on the prospects for this vision.

So what kind of foreign policy should Japan aim for in the future? It would be desirable if, via Japan, the US were to have an economic framework of some form or other with the East Asia region. It is, therefore, important not to give up on the TPP. I think it would be wise not to let the TPP die, but rather to ratify the TPP in the other 11 member countries excluding the U.S., and to leave the door open for U.S. participation.

At the same time, in discussions within the context of the new Japan-U.S. economic dialogue, Japan could perhaps incorporate TPP-type elements into the bilateral economic framework between Japan and the U.S. Not forgetting that, in the TPP consensus-building process, Japan had to overcome difficult issues in areas such as agriculture. If the U.S. were to demand bigger compromises than those Japan made in the TPP negotiations in the form of a bilateral FTA, the U.S. would doubtless be criticized for being overly selfish and this is actually inconceivable.

Japan should definitely proceed with the RCEP and the Japan-China-South FTA. Japan should not be wary about the RCEP, etc. on the grounds that, now the TPP is adrift, China, with its enormous market, may take the lead. It was Japan that balanced things out by opening the RCEP up to Australia, New Zealand and India in the first place instead of an FTA based on Japan, China, South Korea plus the ASEAN member countries. With China still not recognized as a market economy, it is obvious that Japan should take the lead on trade rules.

Maintaining sufficient deterrent force through the Japan-U.S. security structure while at the same time enjoying economic cooperation with East Asia under a Japan-U.S. framework and leading a regional economic framework that draws in China- this is precisely the vision of foreign relations that is in Japan’s national interests.

With the majority of political appointments yet to be filled, the structure of the relevant ministries and offices of U.S. government is still not in place. The coming meeting will, therefore, probably have the nature of a kickoff meeting for the new Japan-U.S. economic dialogue. If possible, Japan should establish a fairly long-term framework or position around twice a year.

Also at the U.S.-China Summit Meeting on April 6 and 7, the establishment of new bilateral economic discussions was agreed. I hope that the new economic dialogue will be a meaningful meeting, with thought given to a framework for trilateral economic discussions between the U.S., Japan and China in the future.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 13 April 2017 under the title, “Nichibei keizaitaiwa no shoten (II): Bei to higashi ajia no kakehashi ni: Chugoku fukumu kyogiwakugumi shiya (Japan as a Bridge Between the U.S. and East Asia: Perspective on a framework for discussion which includes China s).” The Nikkei, 13 April 2017. (Courtesy of the author)