Agenda for BOJ Governor in Second Term I: Japan’s Deflation Is Almost Fixed but Needs Some Modifications—No Further Reflationary Policy Required

Key Points:

- Avoid real wages falling amid inflation targeting

- Improve messaging and reduce purchases of exchange-traded funds (ETFs)

- Further monetary easing policy may face criticism from abroad

Prof. Kitasaka Shin-ichi

It has been five years since Kuroda Haruhiko was inaugurated as governor of the Bank of Japan (BOJ). The government has nominated Mr. Kuroda for a second term. Mr. Kuroda’s nomination was among those submitted to the Diet, which included nominations for two new deputy governors for the bank. In this article, I intend to review the BOJ’s monetary policy over the past five years and point out challenges confronting Japan’s central bank, which will be led by the reappointed governor.

BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda launched a dramatic monetary policy aimed at achieving a 2% inflation rate, introducing quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (QQE) soon after he came on board in April 2013. The BOJ announced the expansion of its QQE program in October 2014 in view of the weak demand following the consumption tax hike. In January 2016, the central bank moved to introduce a negative interest rate policy out of concern for Japan being trapped in a deflationary economy again because of the rising yen and declining crude oil prices abroad.

The bank viewed two asset prices, in other words, currency exchange rates and equity prices as significant transmission channels in terms of the impact of its monetary policy on the actual economy. Traditionally, the BOJ adopted a monetary easing policy involving reducing the discount rate as a means to stimulate the economy, encouraging banks to lend money to businesses, but this strategy does not seem to work well due to the weak financing needs in the current private sector of Japan.

In fact, the weakened yen was helpful for boosting earnings for the Japanese companies. The BOJ measures involving QQE, additional easing and the negative interest rate policy weakened the yen, resulting in higher corporate earnings that eventually sustained the overall economy. It seems conventional that the bank carefully avoids commenting on the impact of its monetary easing policy on the currency markets, because they are aware that they run the risk of having the policy misinterpreted by foreign governments as an act of currency manipulation.

The impact of the QQE policy was even more visible in the stock market. The BOJ started buying exchange-traded funds (ETFs) in 2013, and spent 1 trillion yen. The purchase amount of ETFs expanded to 3 trillion yen in 2014 and grew to 6 trillion yen in 2016. Although it is unusual for a central bank to purchase equities in large quantities, the stock market serves as an important transmission mechanism for the monetary policy to impact the actual economy, according to the empirical analyses published by Honda Yuzo, Professor at Kansai University, and others. Sustained stock prices stimulated the economy and helped to eliminate deflation. It is also noteworthy that the BOJ succeeded in maintaining the consistency of its monetary policy by switching the focus from the quantity of bonds purchased to interest rates. Mr. Kuroda announced that the central bank would continue buying government bonds so that the amount it held of the outstanding JGB would increase by at least 50 trillion yen annually. Additional easing measures were announced in the fall of 2014, which included a boost in annual purchases of long-term JGBs to 80 trillion yen from the initial 50 trillion yen. But a huge debt purchase such as this raises the question about its sustainability in the long term with consideration for the amount of bonds issued by the government and the level of demand from banks to take advantage of the extra cash.

The central bank of Japan adopted negative interest rates, aiming to maintain consistency and achieve further enhancement for the monetary easing by shifting its policy focus from the quantity to interest rates. However, the negative interest policy had side effects, causing instability in the markets with long-term interest rates lowered to unexpected levels. In an attempt to tackle this situation, the bank implemented a new policy in September 2016, seeking to control the yield curve for the 10-year government bond.

When Mr. Kuroda was inaugurated as BOJ Governor, he pledged to achieve a 2% inflation target in two years. Today he faces strong criticism, because the bank has yet to meet that target five years later. On the other hand, it is obvious that Mr. Kuroda has made remarkable achievements as the central bank governor if we examine the trend of consumer prices over a long period.

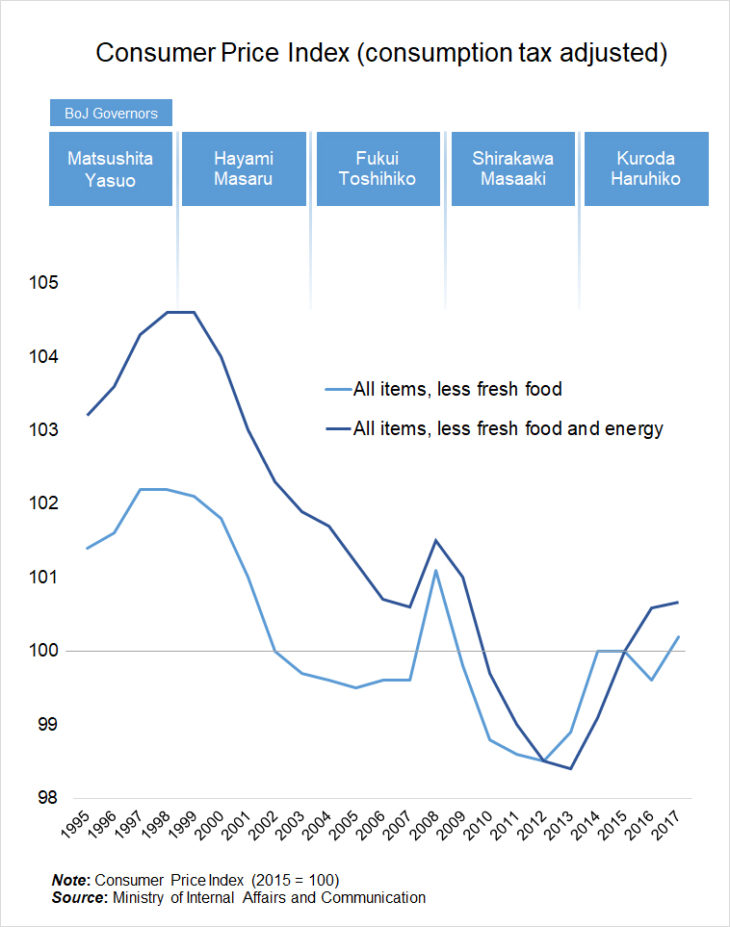

Japan’s consumer price index (CPI) peaked when the financial crisis hit in 1998, and it continued to decline almost persistently (Refer to Figure) for the next 15 years, until Mr. Kuroda came on board. The CPI experienced a significant plunge particularly during the years following the global financial crisis that started in the fall of 2008. When Governor Kuroda was inaugurated in April 2013, the dollar stood at the mid-90 yen level, suggesting that the value of the Japanese yen was too strong domestically and internationally at that time. The excessive appreciation of the yen led to creating the most challenging business environment for domestic manufacturers and service providers, making it a top priority for Japan to put an end to the deflationary economy.

Under these circumstances, Governor Kuroda demonstrated his strong leadership and succeeded in boosting the CPI over the last five years, given the consistent recovery in the global economy, although there was a reactionary plunge in demand following the consumption tax hike and a sharp decline in crude oil prices. Mr. Kuroda actually succeeded in bailing the nation out of deflation, which had never been achieved by his three predecessors. This is indeed a great achievement.

Under the current economic situation, which is no longer in deflation with a sustained decline in prices, achieving the price stability target of 2% does not hold much significance. When implementing a monetary policy with a certain inflation target, it is important to create a policy framework aimed at facilitating steps toward a certain qualitative goal. It is significant to have such a policy framework, because it will serve as an anchor to stabilize people’s expectation of prices, facilitating efforts to identify reasons for any failure to achieve the target.

BOJ’s aggressive monetary easing policy over the last five years has revealed structural problems in the Japanese economy, which seems to have limited strength to increase prices. An immediate cause of the sluggish price hikes seems to be deeply rooted in deflation-oriented mindsets among companies, accompanied by indirect factors, including a labor market with limited upward pressure on wages, weak price competitiveness that makes it difficult for firms to raise sales prices, and the fiscal deficit as well as problems facing the pension scheme that makes it difficult for the government to eliminate lingering concerns that people have about their future. Given that the current situation is no longer in deflation with a sustained decline in prices, Japan must prioritize and address these structural problems in its economy.

The government has reappointed Governor Kuroda and BOJ Executive Director Amamiya Masayoshi as deputy governor. I am comfortable with the nominees announced by the government in light of their achievements. It was also announced that Professor Wakatabe Masazumi of Waseda University had been nominated as the other deputy governor, because the government was keen to place an advocate of aggressive easing (reflationist) in the position, according to sources. It will be necessary for the new BOJ leadership team to have a strong determination to steer Japan away from returning to deflation with a flexible approach for responding to the ever-changing economic conditions.

If the major enterprise unions fail to secure a 3% increase in their 2018 spring wage negotiations, bolder monetary easing as advocated by the BOJ reflationists will make it highly likely that real wages run the risk of falling in value, keeping a lid on consumer spending. Japan must prevent wages from falling in real value ahead of the consumption tax hike planned for October 2019. Compared with five years ago, it seems that the reflationist assertion prioritizing an increase in consumer prices has become less significant for managing the economy.

The most important task for the BOJ under the new leadership will be to enhance market communication. Following the interest rate hikes announced by the Federal Reserve, long-term interest rates in the United States started to rise in late 2017, causing a change in the flow of funds. Given this situation, Japan’s low interest rate policy has fallen under the global spotlight, making it more important for the central bank to stabilize the market outlook for interest rates.

In this regard, federal funds rate forecasts (known as the “dot plot”) released by the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee (FOMC), should provide some insights. The BOJ releases an Outlook Report regularly, presenting monetary policy members’ projections for economic activity and prices in Japan, but this report does not offer an outlook for interest rates. If the bank chooses to release a report comprised of monetary policy committee members’ projections for interest rates, it would be helpful for the market to become stabilized and recover its lost function as a leading indicator for interest rates. Releasing the interest rate forecasts will help to avoid unnecessary market speculations with regard to each comment made by the BOJ executives and the money market operations conducted by the bank on a daily basis. Furthermore, this approach represents an excellent dialogue with the market, which will be very helpful as a communication tool for the bank when moving to exit from monetary easing or when it is necessary to accelerate the easing.

Secondly, it will be necessary for the bank to minimize the side effects of the continued monetary easing in view of the limited growth potential for the Japanese economy. In this regard, the BOJ must change its policy of purchasing large quantities of ETFs. As Professor Omura Keiichi of Waseda University pointed out (Nihon keizai shimbun, February 16, 2018), the BOJ’s ETF purchasing program will distort the stock market and eventually affect negatively businesses in the private sector in the medium- and long-term. This program was effective in eliminating deflation in the economy during the initial years of its adoption, but the protracted purchasing appears to be disadvantageous to the economy in general. Therefore, I believe it will be necessary for the bank to reduce the pace of ETF purchasing at the appropriate time.

Seeking an appropriate opportunity to exit from the monetary easing program will be another large challenge for the BOJ under new leadership, but it appears that it will take some extra time for the bank to be able to implement the exit program. It will be possible for the bank to achieve an inflation rate close to 2% in or around the fall of 2019, when the consumption tax rate will increase on the assumption that no significant changes will occur in the global economy and currency markets. However, I believe it will be good for the economy if the BOJ continues its monetary easing policy until they confirm that a possible reactionary plunge in demand has been eliminated, following the planned consumption tax hike. Financial institutions will remain challenged by the on-going economic conditions for some time to come, but I hope that the structural problems involved in the economy will be solved to a certain extent in the meantime, along with the enhanced competitiveness achieved by the private sector as well as further improvement in the outlook for household income.

An immediate challenge facing the Japanese economy is the excessive appreciation of the yen that has developed since the beginning of this year, given that investors around the world have become increasingly risk averse. If the rising yen appreciates beyond 100 yen against the US dollar, the BOJ will probably be under pressure to expand its monetary easing program. In that case, it would be effective to lower long-term interest rates (yields for JGBs with more than 10 years to maturity) under the yield curve control policy.

Another immediate challenge is that the BOJ’s monetary easing program may trigger political accusations from abroad in terms of currency devaluation claims, given the Federal Reserve’s plans to hike interest rates and the European Central Bank’s (ECB) steps toward exiting its monetary easing program. The Trump administration in the United States sees the bilateral trade imbalance with Japan as a problem, and might assert that Japan is engaged in unfair manipulation of the currency markets to weaken the yen by taking advantage of its monetary easing policy. Japan’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) gap and inflation rate have both been in the positive territory. In view of that, it seems difficult for Japan to defend its argument by simply stating that its monetary easing policy is solely designed to eliminate deflation in the economy.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 13 March 2018 under the title, “Nichigin shintaisei no kadai I: Datsu defure hobo tassei, bichosei wo—Isso no rifure seisaku wa fuyo (Agenda for BOJ Governor in Second Term I: Japan’s Deflation Is Almost Fixed but Needs Some Modifications—No Further Reflationary Policy Required).” The Nikkei, 13 March 2018. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- BOJ Governor

- Kuroda Haruhiko

- monetary easing policy

- qualitative monetary easing

- deflation

- real wages

- exchange-traded funds

- Japan’s consumer price index

- price stability target

- Open Market Committee

- yield curve control policy

- trade imbalance