Agenda for BOJ Governor in Second Term II: Further commitment to do whatever it takes to achieve 2% inflation target entails a risk—It is important to return to the principles of the “joint statement.”

Key Points:

- Inconsistent priorities have made monetary policy inflexible.

- The 2013 joint statement called for the establishment of a sustainable fiscal structure.

- A widening disparity between BOJ’s words and actual intentions appears to involve a risk.

Prof. Okina Kunio

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) has demonstrated its unwavering dedication to the achievement of a 2% inflation target over the last five years.

In his inaugural news conference held five years ago, Governor Kuroda Haruhiko referred to the joint statement announced by the government and the BOJ in January 2013 by saying, “It can be summed up as we will do whatever it takes to achieve 2% inflation at the earliest date possible.” Deputy Governor Iwata Kikuo also expressed his strong commitment to achieving the price stability target no matter what the situation would be by saying, “We should not make excuses by saying that it wasn’t our responsibility if we fail to achieve the inflation target.”

After five years of this policy, consumer prices excluding perishables in January of this year rose 0.9% year on year, while those prices excluding energy as well (core CPI) rose only 0.4%. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate for the latest month has fallen to some 2% amid the strong recovery of the global economy.

Given that the pledged target has remained significantly unachieved to date, should the BOJ continue to pursue its current policy of placing the 2% price stability target above everything else? There has been no change in Governor Kuroda’s stance to date. Newly appointed Deputy Governor Wakatabe Masazumi is known as a “reflationist” or a vocal advocate of aggressive easing, like Iwata. Unlike his predecessor, Wakatabe appears to be keen on ramping up stimulus by using fiscal policy in order to achieve the target. It seems obvious to me that the appointment of Wakatabe as deputy governor reflects the preference of the Abe administration.

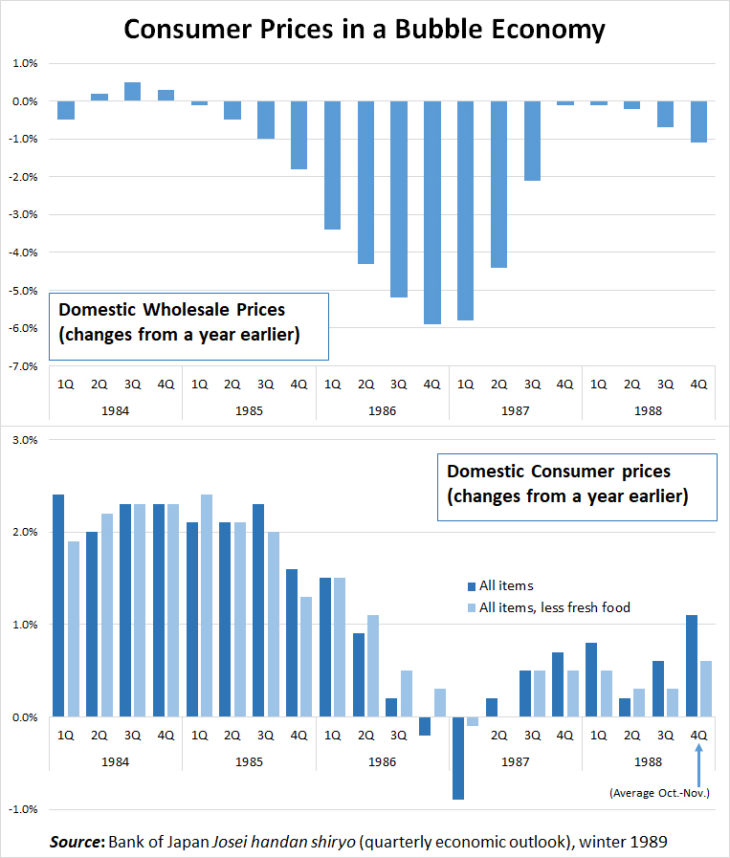

On the other hand, it seems quite likely that further easing to achieve the price stability target when the economy is at full employment will destabilize the financial system. In this regard, the Japanese economy in the late 1980s is a case in point. During this period, Japan’s wholesale prices dropped significantly with a limited increase in consumer prices of less than 1%. (Please refer to the Figure.) These price conditions were the main reason why the BOJ had great difficulty in correcting its loose monetary policy despite the pronounced growth of an asset price bubble.

The bubble subsequently burst and the Japanese economy began suffering a prolonged recession for a number of years to come. By going through this difficult period, the BOJ became painfully aware that it must carefully monitor not only prices but also the economy as a whole, including financial imbalances in particular.

Almost concurrently with the period of the post-bubble years in Japan, many central banks in industrialized economies were still in the process of beating the excessively high rate of inflation with inflation targeting, which came under the spotlight as a tool for overcoming inflation. A formidable amount of related research papers was produced by academia. Consequently, most of the central banks adopted an inflation target of something like 2%. The limitations inherent in this monetary policy experienced in Japan were not clearly understood by the central banks in Europe and the United States until after the global financial crisis in 2008, when the policy had already been implemented by many of them.

Looking back on half a century, seemingly legitimate reasons on different occasions (e.g. the battle against the revaluation of the yen, international cooperation aimed at weakening the dollar, growth driven by domestic demand) have, along with the persistent fears of the yen’s appreciation, made the monetary policy inflexible. In light of a key lesson from past experience, I believe that further commitment to realizing 2% inflation in the near future by monetary policy alone would entail a significant risk.

As examined above, Japan’s monetary policy has been in line with what Governor Kuroda has said and the expectations of the Abe administration, while involving a significant risk associated with it. What, then, should the BOJ’s policy framework be for the next five years?

It should be the most realistic approach for the new leadership to return to the principles of the joint statement announced by the government and the BOJ that I discussed earlier in this article, given that Governor Kuroda has often stated that the joint statement is still in effect, and Prime Minister Abe Shinzo made it clear that he has no intention of revising the joint statement at the House of Councilors budgetary committee meeting on March 2, 2018.

Here, I would like to examine what the joint statement was like. In his inaugural news conference five years ago, Governor Kuroda said, “It can be summed up as we will do whatever it takes to achieve 2% inflation at the earliest date possible.” Indeed, in the accord, the BOJ established its price stability target in terms of consumer prices increasing 2% over the previous year, emphasizing the early achievement of the target.

The joint statement, however, also calls for the BOJ to ascertain whether there is any significant risk to the sustainability of the economic growth, while examining possible risks such as the accumulation of financial imbalances.

In a speech explaining the joint statement three days after its release, Shirakawa Masaaki (BOJ’s ex-Governor) stated that overseas central banks do not specify dates for achieving price stability irrespective of the adoption of inflation targeting. He also said that the BOJ’s view on aiming for sustainable price stability is based on a similar understanding, and that it will bear in mind the risk of financial imbalances, while not confining itself to a specific date for achieving the inflation target.

Currently, the BOJ’s yield curve control (maneuvering both short- and long-term interest rates) has led to the loss of fiscal discipline by the government, with bank profits being squeezed by a vanishing lending spread. This policy has also invited the significant decline of the functioning of the long-term government bond market, distorting price formation in the stock market through the BOJ’s massive purchases of exchange-traded funds (ETFs). The joint statement does not give higher priority to the achievement of the inflation target over maintaining financial stability.

In the accord, the government pledged to steadily promote measures aimed at establishing a sustainable fiscal structure in an effort to strengthen policy coordination with the BOJ. While pursuing further monetary easing on a large scale would run the risk of making fiscal discipline weak, it does not seem realistically possible for the BOJ to directly disagree with the government taking advantage of low interest rates in government financing. The joint statement between the government and the BOJ must have been an important framework in order to call for the establishment of a sustainable fiscal structure used as a condition for further commitment to monetary easing.

It is likely that the government and the BOJ will pursue the price stability target further without conducting a comprehensive reassessment of the principles of the joint statement. What would then happen to the fiscal management?

In the event of a negative shock to the economy, the BOJ would come to a deadlock without any effective monetary policy. In this case scenario, the central bank’s monetary policy will be coordinated more closely with the government’s fiscal policy without being debated under the banner of monetary easing aimed at a 2% inflation target, making it possible for the government to obscure monetaization and its influence on the monetary policy by emphasizing that the BOJ manages monetary policy alone with independent criteria.

Meanwhile, it will become far more necessary for the BOJ to revise its monetary policy as long as the economy remains at full employment, even if the price stability target fails to be achieved. In the event of this case scenario, it is possible that the BOJ will leave the disparity as is on purpose between the words placing the achievement of the price stability above all else and the real intention. In fact, the BOJ has clearly changed its policy priority from the quantity to controlling interest rates by significantly reducing the amount of asset purchases while officially advocating the need for JGB purchases of 80 trillion yen per year. It seems to me that the BOJ’s leadership team maintains a practical approach with the rather philosophical view that it will be OK as long as the players in the market understand the BOJ’s real intentions, despite certain inconsistencies.

However, this type of approach lacks accountability and involves a significant risk. Market players usually try to interpret the BOJ’s real intentions every time the bank executives refer to the issues related to price stability efforts. BOJ’s messaging is interpreted as a signal to, say, induce the yen’s appreciation, to support the stock market, and to lay the groundwork for exit strategies. Should there be any noticeable gap between the market estimations and the BOJ’s real intentions, the market will become destabilized.

This offers certain points for discussion when it comes to talking about the exit strategy for the negative interest rate policy. It is likely that the financial imbalances that have been obscured by the negative interest rate policy will become evident when exiting from the ultra-loose monetary policy.

It will therefore be necessary for the BOJ to secure greater leeway for its monetary policy by hammering out specific measures designed to minimize the shock to the financial market as well as the losses being forced on financial institutions, while restoring the sustainability of government finance in advance when it comes to taking steps toward the exit. In order to do so, the government and the BOJ should exchange views, including a number of proposals that have already been offered, in an open manner with the private sector experts as well.

The BOJ, however, continues to reject any discussion of exit strategies because the prospect for achieving the inflation target remains out of view. Given this situation, concerns might start looming rapidly that the government and the BOJ will pass the impairment of the BOJ’s balance sheet on to the financial institutions by adopting measures including a significant increase in the reserve requirement ratio for financial institutions when moving toward an exit.

In January 2016, the BOJ unexpectedly introduced a negative interest rate policy, of which it had denied any possibility until its announcement. The BOJ may have made the surprise move because it was concerned that the move would invite strong criticism from financial institutions that would see their profits being squeezed, and the policy adoption would eventually be deadlocked if the introduction was announced in advance. Paradoxically, this surprise move made by the BOJ has led to a more persistent deflationary mindset and made banks into the BOJ’s enemies. Many of the market players have painful experience of Governor Kuroda’s tactful announcements that are often intended to produce a market surprise.

As Governor Kuroda attempts to reject discussions of the exit strategies more forcefully, his stance will make the market players even more concerned about the exit program, leaving them speculative regarding any news. This will further restrict BOJ’s dialogue opportunities with the market, creating a vicious cycle. The BOJ must improve its dialogue with the market and assume accountability without creating a “Taper Tantrum.”

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 14 March 2018 under the title, “Nichigin shintaisei no kadai II: Bukka-mokuhyo no hitoriaruki kiken—‘Kyodo seimei’ no zentai saikakunin wo (Agenda for BOJ Governor in Second Term II: Further commitment to maintaining the price stability target entails a risk—It is important to return to the principles of the “joint statement.”).” The Nikkei, 14 March 2018. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- 2% inflation target

- Kuroda Haruhiko

- Iwata Kikuo

- CPI

- Wakatabe Masazumi

- fiscal policy

- bubble burst

- global financial crisis

- battle against the revaluation of the yen

- international cooperation aimed at weakening the dollar

- growth driven by domestic demand

- yield curve control

- ETFs

- JGB 80 trillion yen per year

- negative interest rate policy

- exit strategy

- exit program

- Taper Tantrum