With Yen at 50-Year Low, Bank of Japan Tweaks Monetary Easing Policy: Premature to tighten monetary policy like other major advanced economies

On January 22, 2013, then Prime Minister Abe Shinzo received the report of the joint statement by the government and the Bank of Japan. Abe said, “This joint statement is for making a bold review precisely on monetary policy towards breaking out of deflation, and I believe it is in a way a groundbreaking document in terms of monetary policy. Especially with this new effort, which can also be called a regime change, we must break out of deflation.”

Photos: Cabinet Public Affairs Office

Hayakawa Hideo, Senior Fellow, Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research

Senior Fellow, Hayakawa Hideo

Some three years ago, much of the developed world had joined Japan, succumbing to Japanification, a term used to describe a combination of low growth, low inflation, and low interest rates. However, the COVID pandemic completely transformed the global economic landscape. Now, the biggest economic challenge facing the world is rising inflation, and central banks around the world are rushing to tighten monetary policy to quell inflation, with the Federal Reserve Board (FRB) leading the charge. Japan has also seen growing discontent with the rising cost of living, as consumer inflation (the rate of increase in the consumer price index [CPI]) hit 3 percent for the first time in three decades and the yen weakened dramatically. Calls for the Bank of Japan (BOJ) to raise interest rates are also not uncommon.

However, the important point here is the huge difference between inflation in Japan and inflation in other major economies. In fact, whereas many Western economies are facing inflation in the range of 8-10 percent for the first time in around 40 years, Japan has 3% inflation. The high resources prices resulting from the Ukraine crisis are a problem faced by all economies alike and since Japan also has a weak yen to contend with, it comes as no surprise that rising import prices are driving consumer inflation in Japan, more so than in other economies. The reason inflation remains low in Japan nonetheless is that whereas in the United States it is feared that higher wage growth stemming from labor shortages will lead to further price increases, in Japan wages have not increased at all.

In the “Opinion Survey on the General Public’s Views and Behavior” conducted by the BOJ in September 2022, almost half of the respondents said that present price levels “have gone up significantly” compared with one year ago and almost 90% of respondents thought that the rise in prices was “rather unfavorable.” The reason why consumers claim they are struggling to make ends meet under mild inflation of 3% is probably that their wages have not gone up. According to a survey by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), in 2022, the average wage hike rate resulting from spring negotiations was 2.2%, or around 0.5% excluding regular wage increases. A fair assessment of Japan’s current position is perhaps that Japan has yet to completely escape deflation whilst at the same time facing mild inflation.

My take on the situation is that the reluctance of corporations to raise wages despite improved earnings is attributable to “learned pessimism.” Ever since the financial crisis in Japan 26 years ago, corporations have learned through lessons such as the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 that the key to corporate survival is to set aside internal reserves in case of emergency. I suspect that the use of internal reserves to prevent capital shortfalls during the suspension of corporate activities in the first wave of COVID-19 also served as a success story for defensive management.

It was with the intention of breaking such entrenched pessimism (the BOJ called it a “deflationary mindset”) that, almost 10 years ago, the BOJ introduced bold monetary easing, a policy dubbed Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE), setting a 2% inflation target. Unless wage growth is achieved, once the surge in resource prices comes to an end, inflation will probably drop below 2%. What is more, given that in January 2013, before Kuroda Haruhiko became Governor, the BOJ clearly pledged in a Joint Statement with the government to achieve the “price stability target at 2 percent” at the earliest possible time, it is perhaps premature for Japan to start tightening monetary policy at this moment in time.

A weak yen does not “benefit” the Japanese economy

That said, I cannot help feeling that something is off with the BOJ’s stance of trying to stubbornly stick to its current monetary policy, repeating that a weak yen benefits the Japanese economy. I say this because, from the outset, QQE was an experimental policy which was introduced in a bid to escape persistent deflation and which, despite failing to produce any clear results in the initially set time horizon of two years, is still being maintained without any definite exit strategy.

Exchange rate fluctuations always benefit some and negatively impact others. In the case of a weak yen, the winners are large, global corporations and the losers are domestic demand-type SMEs and households. Some still argue that the benefit to the former is only slightly more when calculated with an econometric model but I do not give much weight to such arguments. Previously it may have been the case that strong export growth driven by a weak yen leads to improvement in the overall Japanese economy, which ultimately also benefits SMEs and households. However, these days when changes such as the shift of production overseas mean that there is hardly any growth in exports even under a weak yen, a weak yen is unlikely to benefit SMEs and households.

Of course, the yen rises and falls against other major currencies; however, Abenomics and QQE were policies aimed at keeping the yen weak. On top of this, there has been the recent reduction in corporate tax on the one hand and measures that negatively impact households such as social insurance premium hikes on the other. Consequently, Japan’s growth rate over the past decade is virtually the same as the decade before. A breakdown reveals virtually no growth in consumer spending as a major feature (in contrast to higher growth in exports and capital investment). When an excessively weak yen like the one we are seeing now is added into the mix, then the negative impact on households is clear. It seems wrong to say that such a situation “benefits the whole economy.”

Giving more flexibility to short- and long-term interest rate control

And so how should the BOJ respond? Here we need to remember that the BOJ has implemented an “abnormal” financial policy (=short- and long-term interest rate control [Yield Curve Control, YCC]), not only setting the short-term policy interest rate at minus 0.1% but also keeping the long-term interest rate (more specifically the 10-year Japanese Government Bond yield) around zero (more precisely zero ±0.25%). In September 2016 when YCC was first introduced, it was explained as a means of continuing to implement even more powerful monetary easing after short-term interest rates reached zero percent. However, by its nature, YCC increases exchange rate volatility. In other words, if overseas interest rates rise, even when the short-term policy rate is fixed, usually the shock is absorbed via two routes i.e. an increase in domestic long-term interest rates and depreciation of the domestic currency. However, when the domestic long-term interest rate is fixed through YCC, the only way to absorb the shock is through even greater exchange rate volatility.

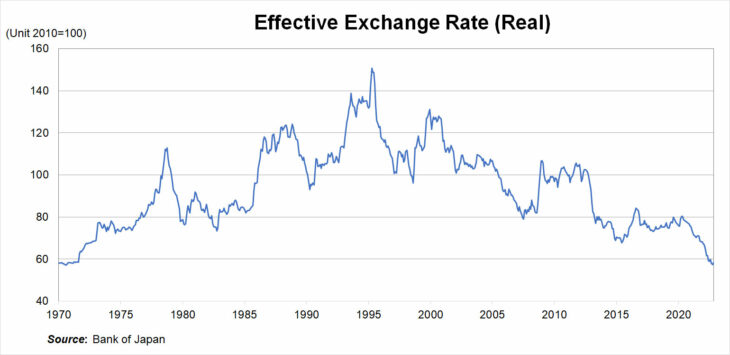

As everyone knows, the yen fell dramatically from the beginning of 2022, weakening from 110 against the dollar at the beginning of the year to past 150 against the dollar for a time in October. Such a dramatic weakening of the yen is, of course, largely attributable to the fact that the FRB raised interest rates at a far faster pace than the markets anticipated but at the same time the YCC policy framework is likely to have amplified the weakness of the yen against the dollar. This is not something which occurred to the yen-dollar exchange rate only. Furthermore, in a situation where inflation in Japan was much lower than in other advanced economies and so from the viewpoint of purchasing power parity (PPP), appreciation of the yen would have come as no surprise, depreciation of the yen continued. Analysis of the real effective exchange rate, which also takes other exchange rates into consideration and reflects the difference between inflation rates (see Fig.), shows that the yen is currently at its lowest level in 50 years, a level not seen since 1973 when Japan adopted the floating exchange rate system.

YCC is a policy which increases exchange rate volatility and not a policy which only works to weaken the yen. YCC could lead to a much stronger yen in a situation where, for example, the FRB succeeded in controlling inflation in the United States and started to cut interest rates. At any rate, if excessive exchange rate volatility is not ideal then it may be advisable to give more flexibility to the YCC policy. In fact, the BOJ has twice widened the YCC band from 0.1% to 0.25% and positioned this as increased flexibility of YCC and not monetary tightening.

The BOJ had stubbornly refused to give more flexibility to the YCC policy for a while but recently at the Monetary Policy Meeting in December 2022, the central bank decided to widen the band in which it allows the 10-year JGB to move from 0.25% to 0.5%. This move coupled with a slower pace of rate hikes in the United States countered the excessively sharp fall in the yen and may have been a well-timed decision. However, dialogue with the market is still an issue, with Governor Kuroda, who before this decision had said that widening the band around the long-term interest rate would be a de facto rate hike, insisting at a press conference after the decision that the move was not a rate hike. As I have stressed many times before, it is important that experimental policies evolve flexibly in keeping with changes in the environment.

Note: This article was originally published in the December issue of Wedge under the title “50-nen burino Ijona Enyasu suijun: Nichigin no kochokuseisaku, minaoshi no toki (The abnormally weak yen level for the first time in 50 years: The Bank of Japan’s rigid policy, time for a review.)” The author has rewritten it to reflect changes in the situation, such as subsequent policy changes by the Bank of Japan.

Keywords

- Hayakawa Hideo

- Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research

- monetary policy

- monetary easing

- weak yen

- 50-year low

- deflation

- Japanification

- growth

- inflation

- interest rates

- cost of living

- consumer inflation

- Bank of Japan (BOJ)

- “abnormal” financial policy

- Yield Curve Control

- yen-dollar

- effective exchange rate