Thorny issue of whether to maintain 2% inflation target lies in wait in post-Kuroda era: Lessons learned from “slightly harmful, slightly beneficial” unprecedented monetary easing

“What the BoJ wants is not imported inflation which causes hardship but rather to reach the 2% inflation target in a disciplined, stable and sustainable manner via domestic factors. In other words, the BoJ’s goal is for inflation of around 2% to be seen as the norm and be an integral part of people’s lives.”

Photo: AK / PIXTA

Momma Kazuo, Executive Economist, Mizuho Research & Technologies

Executive Economist

Momma Kazuo

Unattainable 2% inflation target

On April 4, 2013, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) introduced “quantitative and qualitative monetary easing” (QQE). Appointed only a month before, Governor Kuroda Haruhiko explained the BoJ’s stance at a press conference as “monetary easing measures of an unprecedented scale.” Ever since then, the BoJ’s policy, which remains in place today, is referred to as “unprecedented monetary easing.”

The unprecedented monetary easing had just one objective and that was to reach a target of 2% year-on-year growth in consumer prices (price stability target of 2 percent, hereinafter “2% inflation target”). It will soon be 10 years since introduction of the policy and the 2% inflation target has yet to be reached. Of course, Japan recently experienced inflation for the first time in 40 years, with consumer inflation rising to around 4% and so my assessment that the 2% inflation target has nonetheless still not been met requires some explanation.

What is happening in Japan now is not inflation driven by a robust economy but rather inflation driven by the pass-through of surging import costs to prices. This “imported inflation” squeezes corporate profits and causes pain to households. What the BoJ wants is not imported inflation which causes hardship but rather to reach the 2% inflation target in a disciplined, stable and sustainable manner via domestic factors. In other words, the BoJ’s goal is for inflation of around 2% to be seen as the norm and be an integral part of people’s lives.

For the 2% inflation target to become the norm, wage growth that outpaces inflation needs to become the norm. The BoJ seems to think that ideally wage growth should be around 3%. This figure is based on various assumptions and so wage growth of 3% is not an absolute necessity; however, wage growth clearly outstripping 2% is probably required.

Not once in the past 30 years has wage growth reached 3%. Labor shortages have become more apparent recently as the economy recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic but, even so, wage growth, with monthly fluctuations smoothed out, has remained in the mid 1% range. To be sure, such wage conditions do not inspire confidence in the BoJ’s 2% inflation target being met.

The economy did improve though…

The unprecedented monetary easing has to be described as a spectacular failure in the sense that a target which was supposed to have been achieved in two years still looks unattainable after ten. However, some might take the view that just because the target was unrealistic, the BoJ was not wrong to set it. And this appears to be the prevailing view.

The unprecedented monetary easing was the “first arrow” of Abenomics. It is true that soon after the introduction of Abenomics, the strong yen corrected and stock prices rose sharply. During 2013, the Japanese economy improved to the extent that the government scrubbed the word “deflation” from its Monthly Economic Report. The economic upturn lasted until the fall of 2018, Japan’s second-longest expansion since the end of World War II. The active job openings-to-applicants ratio was also higher than during the bubble economy.

To what extent the unprecedented monetary easing was an effective policy is unclear but it did, without doubt, lift the mood of financial markets and the mood in general. Former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo who championed Abenomics was asked about his failure to achieve the 2% price target in an interview directly after stepping down as prime minister and he replied that “We fully achieved our goal” because the economy and employment improved (The Nikkei [electronic version], September 30, 2020). At least when he quit, Abe himself did not appear to be fixated on the 2% inflation target itself, saying the focus had been on the economy and employment.

And in fact, it is the economy and employment that are important to the Japanese people. It doesn’t matter to them whether inflation is 1% or 2%, provided prices are stable enough for price volatility not to be a risk. The BoJ might now be coming under fire for causing excessive weakening of the yen but it is not getting much flak for failing to reach the 2% inflation target.

Ultimately, the 2% inflation target can be described as a “symbol” of the intent of the government and the BoJ to overcome deflation and not necessarily a target in a real sense. Which is precisely why there has been no mounting public pressure to revise the target despite the 10-year-long failure to reach it. In other words, it does not matter. Governor Kuroda was reappointed even though the target was not met after five years. With the target still not reached, he went on to become the BoJ’s longest-serving governor, with a tenure of 10 years. This was 10 years during which relations between the government and the BoJ were generally good. To put it another way, for the Japanese public and for politicians, the 2% inflation target is just a target and there would probably be little outcry even if was never met.

Side effects of unprecedented monetary easing

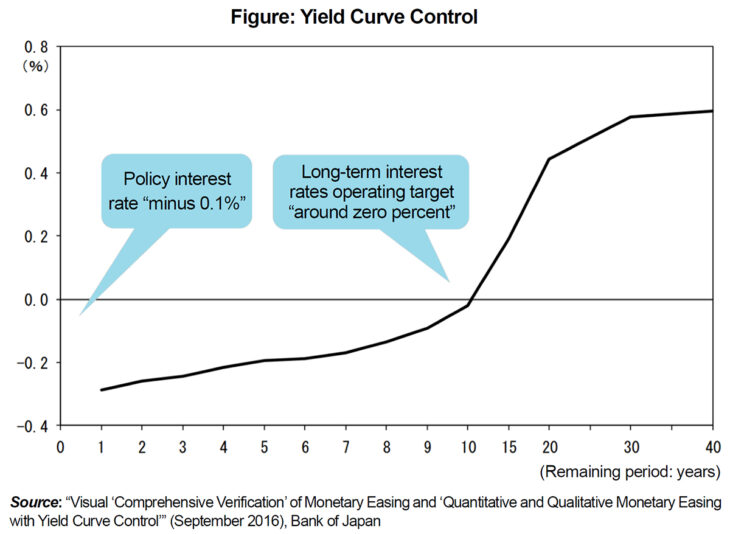

That said, as long as unprecedented monetary easing is linked to the unattainable 2% inflation target, there is the risk that unprecedented monetary easing will remain in place for another five or ten years to come. Unprecedented monetary easing has taken different forms depending on the circumstances at the time and the current framework, introduced in September 2016, is based on Yield Curve Control (YCC).

A yield curve is a graph showing interest rates on bonds for a range of maturities and is usually upward sloping. The BoJ has kept the short-term interest rate, which is the starting point of yield curve, at negative 0.1% and the yield on 10-year government bonds at around zero percent. In other words, in Japan, the yield curve showing short-term interest rates through to the 10-year Japanese Government Bond (JGB) yield has been kept almost flat at around zero. This is extremely unusual and has several side effects.

Firstly, since all interest rates including long-term interest rates are being artificially kept around zero, financial institutions find themselves in a very challenging fund management environment and, what is more, this situation has lasted a long time. This has driven regional financial institutions that were agonizing over the investment of surplus funds to begin with to invest in high-risk debt instruments such as foreign bonds.

Secondly, the government bond market is no longer functioning normally. The “around zero percent” for the 10-year interest rate was defined more specifically as plus or minus 0.25%. From around spring 2022, US long-term interest rates rose sharply and this had the effect of putting upward pressure on Japanese long-term interest rates. At the time, the BoJ stuck with YCC and so frantically bought JGBs. This led to more days when there was no trading due to market dysfunction and the 10-year yield ceased being a reliable benchmark for determining interest rates on corporate and municipal bonds. In December 2022, the range of yield fluctuation was expanded to plus or minus 0.5% but this has not really solved the issue.

Thirdly, YCC amplifies currency volatility. As explained above, since Japanese long-term interest rates are held down even when US long-term interest rates are rising, the interest rate differential between the US and Japan widens more than necessary, amplifying downward pressure on the yen. The impact of YCC on the exchange rate has not been officially recognized, perhaps because foreign exchange policy falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance and the BoJ is in a delicate position. It is an indisputable fact, however, that the financial policies of the US and Japan remained a major theme on foreign exchange markets in 2022.

The challenge is pivoting from unprecedented monetary easing

Governor Kuroda’s second term and 10-year tenure will come to an end in April 2023 and his successor is yet to be decided as of the time of writing. However, whoever the next governor is, the challenge he or she will face in terms of financial policy is already decided and that is pivoting from unprecedented monetary easing by removing negative interest rates and YCC. Broadly speaking “pivoting” brings to mind two scenarios depending on the reason given for the pivot.

The first scenario is where achievement of the 2% inflation target comes into sight and the BoJ prepares for an exit from monetary easing in a dignified manner. As explained earlier, the 2% inflation target is in fact a “3% wage increase target” and, recently, wages are nowhere near this target. However, the Japanese economy is still on the road to recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and labor shortages are already becoming an issue. If labor demand increases further on the back of full-scale recovery in inbound demand, then the possibility that wage growth will increase to around 3% cannot be completely ruled out.

That said, this would signify an unprecedented wage increase unlike any seen in the past 30 years. For average wages to increase by 3%, a pay increase of around 5 percent would need to be achieved in the spring labor offensive. This is because just under 2% of the pay increase negotiated in the spring labor offensive comes from a regular annual raise based on seniority in order to maintain the seniority-wage curve. And so, the Japan Trade Union Confederation or Rengo plans to call for a pay increase of around 5% in this year’s spring labor offensive. However, the final outcome usually falls well short of Rengo’s demand. What is more, unless there is an “unprecedented wage increase” every year not just this year, the BoJ’s 2% inflation target will not be met. I said this scenario could “not be completely ruled out” but at the same time it looks unlikely.

It is the second scenario which is much more likely. Under this scenario, the current wave of imported inflation subsides, highlighting once again the difficulty of the 2% inflation target. In this scenario, even if the BoJ prolongs its monetary easing policy still further, surely it will remove the negative interest rates and YCC which have side effects to avoid causing any problems. If so, then the BoJ’s monetary easing will be “ordinary monetary easing” consisting simply of keeping the short-term interest rate around zero. This scenario would be considered a “framework revision” for limiting the side effects of prolonged monetary easing rather than an exit from monetary easing.

Possibility of “framework revision” this year

As described above, there are two possible financial policy scenarios, the “exit scenario” in which the 2% inflation target is met and the “framework revision” scenario in which the target is not achieved. However, in practical terms, even if the BoJ is going to prepare for an exit, ultimately there are still advantages to making a framework revision as a preliminary step.

This is because going straight from YCC to an exit would be technically difficult. In the case of the monetary easing pursued by other economies, exit signifies the start of short-term interest rate hikes. Since sudden rate hikes can lead to market turmoil, central banks provide forward guidance on their intention to raise short-term interest rates so that markets price in this eventuality and market forces push up long-term interest rates slightly beforehand. However, in the case of YCC, since the central bank fixes the long-term interest rate, market forces cannot be harnessed to “guide it up slightly beforehand.” A sudden hike in the long-term interest rate at the exit will lead to market turmoil.

To avoid this problem, it would be wise to make a framework revision before actually heading towards an exit. If the BoJ stopped controlling the long-term interest rate and just switched to an “ordinary zero interest rate policy” consisting of fixing the short-term interest rate only, the rest of its financial policy would be in line with those of other central banks. It would be better to decide whether to actually head towards an exit i.e. to raise interest rates, based on an assessment of achievement of the 2% inflation target.

Ideally, this framework revision should be completed as soon as possible. Though unlikely, if achievement of the 2% inflation target did become a real possibility, this would fuel market expectation that the “BoJ was about to raise the long-term interest rate.” If the BoJ removes YCC once market expectation is high, the central bank will ultimately be unable to curb the surge in long-term interest rates, causing market turmoil. However, the economic downside risks involved in framework revision at an earlier stage are still huge and the question is whether this will prevent the BoJ from taking action. I believe that framework revision some time this year is perfectly possible provided the BoJ explains that the purpose of the revision is to combat the side effects of YCC and there is no change in its stance of maintaining monetary easing.

“Slightly harmful, slightly beneficial” unprecedented monetary easing

I would now like to try summarizing the historical significance of the unprecedented monetary easing. In fact, opinion on the policy differs widely from a positive evaluation that unprecedented monetary easing contributed enormously to the normalization of the Japanese economy as the first arrow of Abenomics to a negative evaluation that it was extremely harmful and ruined the Japanese economy.

In my view, the unprecedented monetary easing was neither massively beneficial nor massively harmful rather its impact on the Japanese economy itself was “slightly harmful and slightly beneficial.” Starting with the slightly beneficial impact, the unprecedented monetary easing did initially lift the mood of the market and the general mood in some respects; however, it did not go beyond lifting the “mood” and strengthen the Japanese economy. Under Abenomics, Japan marked its second-longest postwar economic expansion but experienced its lowest growth rate in the post-war period. With absolutely no wage growth in real terms, private consumption showed almost zero growth.

At the same time, I believe the unprecedented monetary easing was also slightly harmful. Some economists argue that the unprecedented monetary easing caused Japan to lose fiscal discipline, increasing the risk of “Japan selling” or that it reduced Japan’s growth potential by slowing Japan’s economic metabolism. However, such arguments that “unprecedented monetary easing ruined Japan” have little theoretical basis and are arguments based on personal impressions. And even if Japan has less fiscal discipline or growth potential than before, responsibility for finance and growth strategy lies with the government. From the BoJ’s standpoint at least, this sort of criticism can be easily countered.

It can also be said that my assessment of the unprecedented monetary easing as “slightly beneficial and slightly harmful” is proven by the fact that the unprecedented monetary easing has been in place for 10 years. If the policy was truly effective, it would not have taken 10 years to work and if it was truly harmful, surely it would not have been left in place for 10 years. A policy that drags on and on with no real positive or negative significance is perhaps a fair assessment of unprecedented monetary easing.

That said, as explained earlier, it is a policy with side effects such as (1) a negative impact on the financial system, (2) JGB market dysfunction and (3) amplification of currency volatility. These problems are not so serious as to ruin the Japanese economy; however, they are also not issues which can be overlooked indefinitely as a trade-off for a policy which is only slightly beneficial. Recognizing this situation deep down though perhaps not quite so clear cut in its summary, the BoJ could conceivably proceed with a framework revision whilst at the same time preparing for an exit which may or may not happen.

The biggest achievement of unprecedented monetary easing and the task left behind

I believe that the unprecedented monetary easing had a limited impact on the Japanese economy but a major impact on economic discourse, and a constructive one at that. In my view, it is this impact on economic discourse that is the biggest achievement of the unprecedented monetary easing.

First, the unprecedented monetary easing made it abundantly clear that a lack of monetary easing is not what is really wrong with the Japanese economy. Before unprecedented monetary easing was introduced, it was persuasively argued that the BoJ’s refusal to implement bold monetary easing was to blame for deflation, which was at the root of Japan’s economic woes. The unprecedented monetary easing was a policy which, from the outset, was introduced under political pressure amid such discourse.

However, now most people have realized that however fervently the central bank talks about its 2% inflation target and however much the central bank buys up government bonds, this will not bring about economic growth or wage growth. There are no more calls on the BoJ to further loosen monetary policy and recent economic discourse is focused firmly on the nature of finance and growth strategy, though whether any good answers can be found is another matter.

This constructive shift in discussions on economic policy has occurred precisely because the BoJ went all out with monetary easing in line with its higher mission of achieving the 2% inflation target. I said that the unprecedented monetary easing was not a great policy in any sense but this was because considerable monetary easing had been carried out before the unprecedented monetary easing was introduced and, when the unprecedented monetary easing was introduced, the room for lowering interest rates was already limited. It is because the BoJ stuck to its guns and implemented monetary easing to the point where there was no more room for easing that the unprecedented monetary easing policy now has the power to convince people that “enough is enough.”

Secondly, experts have gained more in-depth knowledge about inflation and financial policy and the quality of analysis and research in these areas has improved. Before introduction of the unprecedented monetary easing, the simplistic argument that “inflation is a monetary phenomena” used to hold some weight.

The phrase “monetary phenomena” is slightly abstract; this is an assertion in a broad sense that “prices are ultimately determined by financial policy” rather than literally equating inflation and money. The basic understanding of most economists used to be that if a central bank strongly committed to the achievement of a fixed inflation rate, 2% for example, then this 2% target would always be achieved.

However, the understanding that, in reality, things are not this simple is gradually gaining traction among experts. The view that inflation was low for so long in Japan because some kind of social norm was at play has also gained weight in recent years. We still have much to learn about inflation including the process by which such “norms” are formed. However, the impetus to seriously research and discuss this problem because it seems more complicated than we had initially thought is one of the byproducts of the unprecedented monetary easing.

Another major point which experts have yet to discuss is “whether the BoJ should maintain the 2% inflation target in the future” and this point can be further broken down into the following two points: (1) whether, with time, the 2% inflation target is achievable through the BoJ’s efforts alone and (2) whether Japan needs a 2% inflation target in the first place. If the answer to (2) is “no” then the 2% inflation target should be removed. And if the answer to (2) is “yes” but the answer to (1) is “no,” then the 2% price target should be the government’s target and not the BoJ’s.

The BoJ is a concerned party and, even with all its talented economists, would struggle to give an unbiased answer to this important question because this would mean negating something it has spent 10 years doing. The question of what should be done about the 2% inflation target is not so much a challenge for the BoJ in the post-Kuroda era but rather an important task for wider economic discourse.

Translated from “Posuto Kuroda ni machiukeru nandai: 2% mokuhyo wa ijisuru bekika—Bieki Bigai’ no Ijigenkawa de Eta Kyokun (Thorny issue of whether to maintain 2% inflation target lies in wait in post-Kuroda era: Lessons learned from “slightly harmful, slightly beneficial” unprecedented monetary easing),” Chuokoron, February 2023, pp. 86-93. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [March 2023]

Keywords

- Momma Kazuo

- Mizuho Research & Technologies

- Japanese economy

- financial policy

- central bank

- Bank of Japan

- BoJ

- 2% inflation target

- deflation

- inflation

- consumer prices

- post-Kuroda era

- Kuroda Haruhiko

- quantitative and qualitative monetary easing

- QQE

- unprecedented monetary easing

- imported inflation

- wage growth

- Abenomics

- Yield Curve Control

- YCC

- bond market

- JGB

- currency volatility

- interest rates

- wage increase

- framework revision