The Future of Fiscal Policy and the Issuance of Government Bonds: Economic power is the foundation of national defense

Ishibashi Tanzan (1884–1973)

Source: Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures (www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/)

Shizume Masato, Professor, Waseda University

Key Points

- Domestic production resources are consumed as defense spending increases

- Ishibashi Tanzan’s argument was realized during the high economic growth period after World War II

- Japan without economic growth will have a heavy defense budget burden

Prof. Shizume Masato

Is it reasonable to increase the defense budget to 2% of GDP? And should the burden be covered by tax increases or government bonds? There is much to be learned from Japan’s modern history regarding the ongoing debate over defense spending.

When Japan was forced to open its treaty ports at the end of the Edo period, neighboring Asian countries fell under Western colonial rule one after another. Under such circumstances, Japanese leaders were faced with the challenge of allocating limited human and material resources to achieve two goals: “Economic development as a source of national power (a wealthy nation)” and “Enhancement of national defense to maintain independence (a strong military).”

When the debate on the subjugation of Korea (1873) arose, the Meiji government decided to promote the policy of encouragement of new industry based on the idea of prioritizing the enhancement of civil power over foreign wars for the time being. After establishing a foundation as a modern state, Japan embarked on foreign wars, but the war expenses of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) amounted to 60% of the GDP at that time. Most of it was financed through government bond issuances including overseas markets. Furthermore, access to international financial markets backed by cooperation with the United Kingdom and the United States made the war possible. However, after the war, Japan had a large amount of external debt, and the burden of principal and interest repayment constrained economic growth.

Japan, which expanded its territory overseas beyond its economic capacity, faced a conflict between maintaining its empire (a strong military) and promoting economic development (a wealthy nation). At this time, the external factor of World War I saved Japan. Militarily, Japan expanded its overseas interests in the Asia-Pacific region without engaging in major battles. Economically, Japan realized rapid growth and became a foreign creditor nation by leveraging exports to European belligerents and their colonies, as well as to the United States.

The Versailles-Washington System, established after World War I, created an international security system in the Asia-Pacific region that included Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and China based on the results of the Washington Naval Conference (1921–22). Disarmament efforts also took place as part of this system.

Toyo Keizai Shinpo (established in 1895, currently Weekly Toyo Keizai)’s Ishibashi Tanzan (1884–1973) suggested to the Japanese delegation at the Washington Naval Conference that Japan should abandon overseas interests to reduce the burden of defense spending and concentrate domestic resources on economic development in order to become a peaceful trading nation—a concept known as “little Japanism.” Yet, the government did not accept his proposal at the time.

However, under the Versailles and Washington systems, the expansion of defense spending was put under control to some extent, making it possible to proceed with urban infrastructure development and the disposal of bad debts, which can be said to be the aftermath of the World War I bubble.

After the Manchurian Incident (1931), Japan acted as a disruptor of the international order. Japan invaded mainland China, effectively violating the international agreement of the Pact of Paris (1928), in which signatories including Japan renounced “recourse to war as an instrument of national policy.” As a result, defense spending continued to increase.

Takahashi Korekiyo (1854–1936), who returned to the post of finance minister for the fifth time at the end of 1931, achieved economic recovery ahead of other countries during the Great Depression through the success of his macroeconomic policy known as the “Takahashi Economic Policy.” However, during budget negotiations with the army and navy, who requested further increases in defense spending, Takahashi faced the challenge of how to allocate limited domestic production resources between enhancing national defense and promoting economic development. Tragically, Takahashi was assassinated on February 26, 1936, by a young army officer who protested against him.

Ishibashi Tanzan, who spoke with Takahashi the year before the February 26 Incident, quoted Takahashi’s statement and said: “Warships do not have the power to create things on their own. If the people were to create only things with no reproducible power like this, the current accumulation of resources would eventually run out, and at the same time the people’s production base would disappear. Here is the reason why the state cannot afford infinite military spending” (Toyo Keizai Shinpo, June 15, 1935). In fact, from the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War (1937) to the end of the Pacific War (1945), Japan followed the path that Ishibashi feared.

Ishibashi’s argument includes important points that are still relevant today. From the Takahashi Economic Policy period to the Pacific War (1941–45), Japan financed its increased defense spending primarily by issuing domestic government bonds. However, regardless of whether the means of raising funds is a tax increase or the issuance of government bonds, if the defense spending is increased, the domestic production resources will be consumed accordingly, so a national burden will occur in any case.

There is also a method of raising funds from overseas markets to temporarily avoid restraints on private demand such as consumption and capital investment. However, in that case, the future burden of principal and interest repayment will occur. Increasing military spending, which does not generate production capacity, leads to restraining investment, which is the source of long-term growth potential. Therefore, it has a negative effect on economic growth.

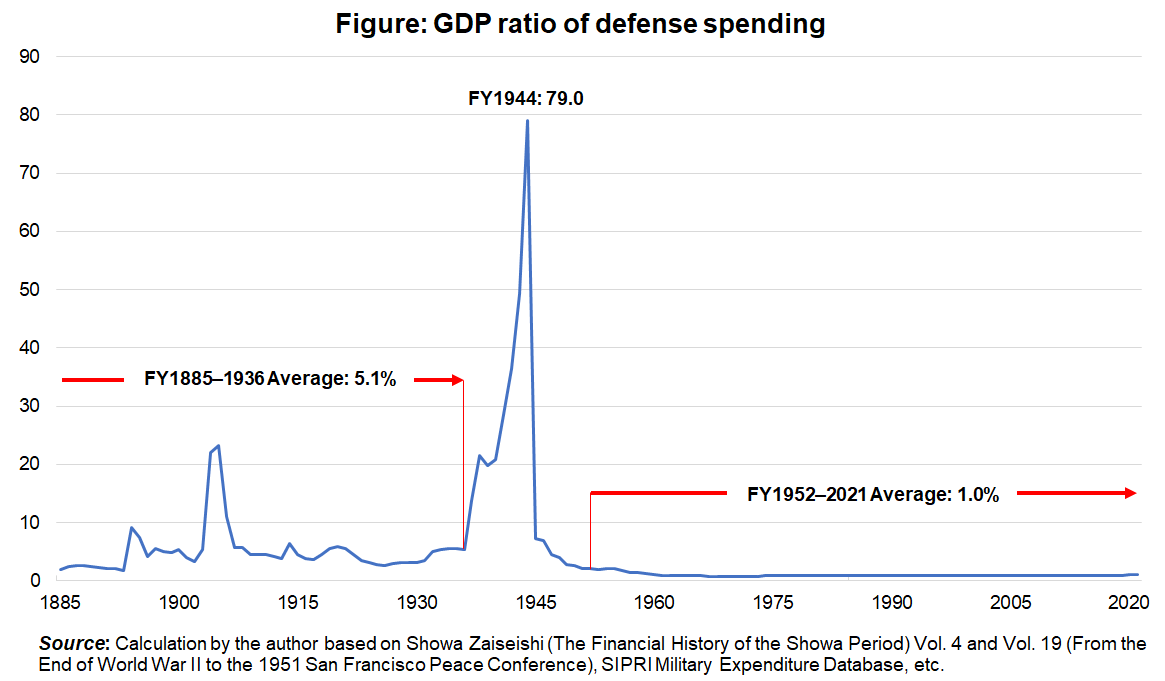

The figure shows the long-term trend of Japan’s defense spending as a percentage of GDP. Prewar defense spending averaged around 5% of GDP (FY1885–1936). It rose to double digits from the Sino-Japanese War to the Pacific War, and in 1944 it is believed to have accounted for nearly 80% of GDP.

Immediately after the end of the war, Japan literally ran out of accumulated resources and was forced to start over with a substantial loss of its production base. Ishibashi published an editorial titled “A start of reborn Japan – The future is really bright,” stating, “We will lose a certain part of our previous territory, and we will also be forced to restrict the armaments industries,” but “I wonder how much (that restriction) will hinder the development of the Japanese people.” (Toyo Keizai Shinpo, August 25, 1945).

In fact, postwar Japan achieved high economic growth by keeping defense spending down from the prewar level of 5% of GDP to 1% and concentrating human and material resources in the civilian sector, which is the source of economic growth. In the 1970s, Japan’s per capita GDP almost caught up with the Western countries and Japan became a major power in the developed world. Based on the lessons of the prewar and wartime years, postwar Japan, which aimed to become a peaceful trading nation with international cooperation as its principle, can be said to have practiced Ishibashi’s “little Japanism.”

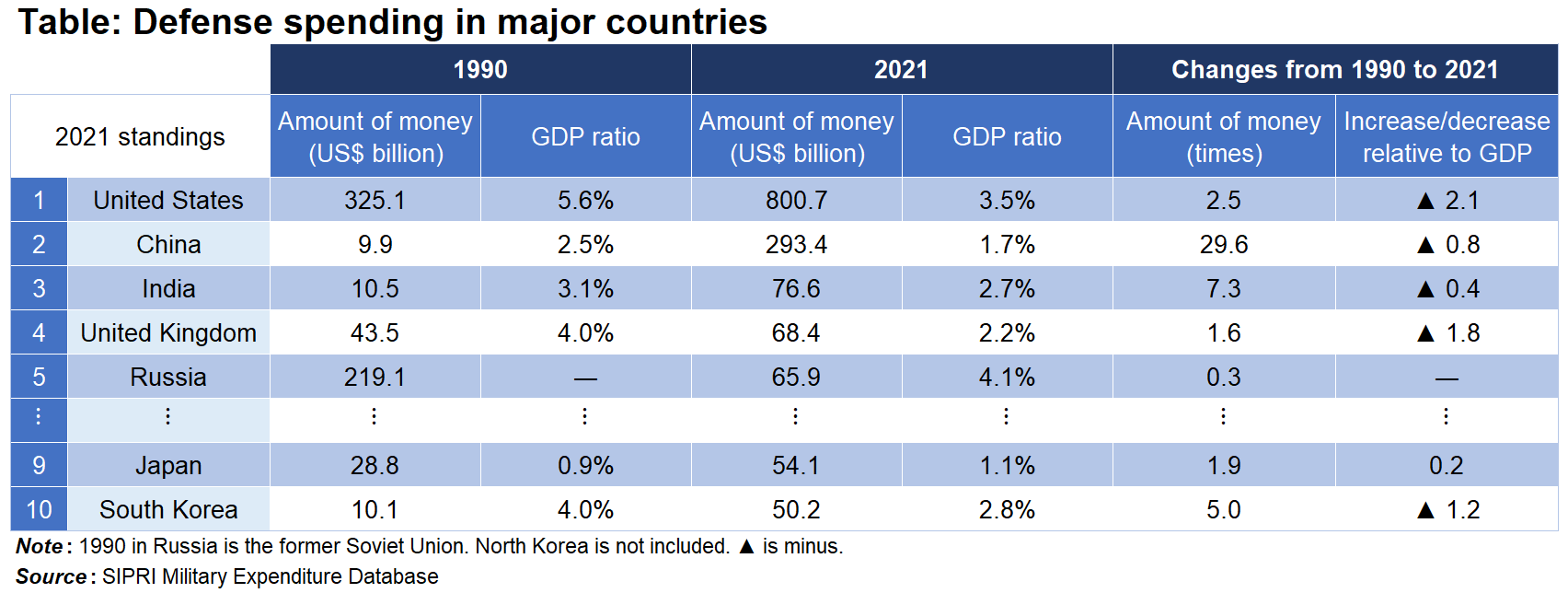

Since the 1990s, the geopolitical situation in Asia has changed significantly (see Table). Looking at the change in defense spending from 1990 to 2021, the United States remains dominant, but China has grown about 30 times in dollar terms while the United States has grown 2.5 times. Although the numbers should be viewed with some leeway, China has moved up to second place, replacing the former Soviet Union. India, which also increased seven times, follows in third place. South Korea ranked 10th after Japan with a fivefold increase.

On the other hand, defense spending in terms of the GDP ratios of the United States, China, India, and South Korea are all declining, and economic growth is leading to a reduction in the burden of defense spending. In Japan, however, although the increase was small at 1.9 times in terms of value, it rose from 0.9% to 1.1% in terms of GDP.

What lessons can be learned from Japan’s modern history regarding the recent debate over defense budgets?

First, economic power is the basis of national defense, not the other way around. In the midst of new challenges such as global environmental problems, depopulation due to a declining birthrate, and responses to geopolitical changes, it is essential for national financial management to consider how to allocate limited human and material resources.

Second, defense spending is just a cost. A national burden will arise regardless of whether the funding is sought from tax increases or government bond issuance. Covering the increase in the defense budget by issuing government bonds may rather constrain economic growth.

Third, Japan succeeded as a peaceful trading nation after the war by taking advantage of its prewar and wartime failures that led to geopolitical instability in pursuit of military power. China and other emerging nations can also learn from this experience. Japan should share its history with neighboring countries and work to reduce tensions in the Asia-Pacific region.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 7 February 2023 under the title, “Zaosei-seisaku to Kokusai zohatsu no Yukue (II): Keizairyoku koso Kokubo no Kiban (The Future of Fiscal Policy and Increased Government Bond Issuance (II): Economic Power is the Foundation of National Defense).” The Nikkei, 7 February 2023. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Shizume Masato

- Waseda University

- defense spending

- defense budget

- defense budget burden

- GDP

- domestic production

- domestic resources

- economic growth

- investment

- overseas interests

- Ishibashi Tanzan

- empire

- strong military

- little Japanism

- Takahashi Korekiyo

- Takahashi Economic Policy

- Russo-Japanese War

- World War I

- Sino-Japanese War

- Pacific War

- armaments industry