The Future of Island Areas: Autonomy and Administration in Island Areas

Kuroishi Keita, Research Fellow, Japan Municipal Research Center

Aogashima is a volcanic island with an area of 5.96 km2 located approximately 358 km south of Tokyo. It is the southernmost and most isolated inhabited island of the Izu Islands. Aogashima Village has a population of 170, and some 20 village officials handle tasks in a variety of areas. The photo shows the island’s caldera and its central cone, Maruyama, which has an elevation of 223 m.

Like peninsulas and mountainous areas, islands are not subject of any institutions or policies that make up a framework that is uniform for Japan as a whole. I would like to discuss the future autonomy and administration of island municipalities by dividing them into four types.

Introduction

Japan, as an “island country,” has more than 6,800 islands, of which about 400 are inhabited. These inhabited islands are sites of “autonomy” that supports the lives of the residents living there.

Moreover, to these residents, the municipalities are the closest administrative body. In this paper, I define municipalities with inhabited islands within the relevant geographical area as “island municipalities,” to which I would like to draw attention.

The environment surrounding island municipalities today is not necessarily so calm. It goes without saying that the arrival of the super-aged society and shrinking population as a serious issue across Japan and the concomitant financial crisis are drawing attention to the future of local autonomy in general. Amid these nationwide challenges, what characterizes the autonomy and administration of island municipalities, which have geographic characteristics that differ from other areas? Moreover, what are the historical contexts of the island municipalities in Japan that form the basis for those characteristics?

If the history and characteristics of areas differ, there should naturally be differences in how autonomy is conducted and what financial and administrative operations are in demand. From this perspective, this study should clarify the need for institutions and policies rooted in local diversity for islands as an area because of their characteristics. Besides islands, Japan also has other areas with various characteristics, such as peninsulas and mountainous areas, so we should expect there to be certain limitations to having institutions and policies within a framework that is uniform for Japan as a whole.

For example, the so-called “424 public medical institutions list,” which was announced by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) in 2019 as a pre-stage to the reorganization of public hospitals, was received with shock in many parts of the country. This new public hospital reform also identified several medical institutions on islands as “medical institutions with revaluation requests,” but some of these were the only hospital on the island, with arguments being made in a framework that would be impossible to implement from the perspective of protecting island residents’ health and local healthcare. Residents and municipalities being thrown hither and thither by this sort of thing is a phenomenon that has not changed much after decentralization. Partly because of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, we do not know if this situation will change in the future, but we can still see how policies uniform for the whole country are being launched without taking into account local characteristics.

Islands are areas that are extremely ill-suited for institutions and policies that are uniform for the whole country because of their geographic characteristics. Why are islands so ill-suited? Below, I will summarize basic information about the history, autonomy, and administration of island municipalities, and then think about how autonomy and administration in island areas may look in the future.

The island municipalities and the state

The main topic for the day is that basic matters on local autonomy are jointly stipulated in the Local Autonomy Act, which is a source of law of the Constitution of Japan. This act makes a nationwide institutional design for municipalities, be they islands or non-islands, but in the Meiji period (1868–1912) when local autonomy came about in modern Japan, there was another different legal system in effect.

In the Meiji period, there was also a municipal system on Okinawa Prefecture and island municipalities, and while its coverage was limited, it instituted a local government system that restricted autonomy more for “island municipalities” than other municipalities.[1] I will not describe the institutions in detail, but the reason for this restrictive local government system for island municipalities was that the popular sentiments and customs of islands used to be on a “lower” level than other municipalities, which made it impossible to implement a nationwide local government system, and this was created instead. The only way to ascertain the actual popular sentiments and customs of islands back then is through research in history and cultural anthropology, but if we consider the social and political environment of the time, another different background comes into view.

The Japanese government in the Meiji period needed to demonstrate Japanese “modernization” to other countries as they were working toward revising the unequal treaties, so they were zealously trying to develop the institutions of modern statecraft, including a local government system. Yamagata Aritomo (1838–1922), who had a big impact on the development of Japan’s modern local government system, advocated the building of a strong coastal defense system, and it was in this historical context that islands were framed as strategically important for foreign relations and defense. With this, they implemented a local government system that allowed for strong governance by the central government, meaning a system that stipulated restricted autonomy from the perspective of the island municipalities.[2] Finally, this system of restricted autonomy was formally abolished in the early Showa period (1926–1941), and a nationwide local autonomy system that also included islands was implemented.[3]

If we examine this historical development, we realize that being an island country, Japan and especially the central government takes great interest in the autonomy of islands areas. Then, special measures on the maintenance of local society were devised for islands in the open sea that make up a national boundary and the “Act on Preserving Remote Islands Areas” was established by Diet members in 2016 with the aim of contributing to the preservation of territorial waters, the exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and such, so the essence really has not changed much even today.

If we say that a state consists of territory, people, and sovereignty, then the island municipalities that are at the frontline of the national border are intimately connected to “territory” and it is of great interest to the central government whether citizens live there or not.

The basic character and issues of island municipalities

(1) Basic types of island municipalities

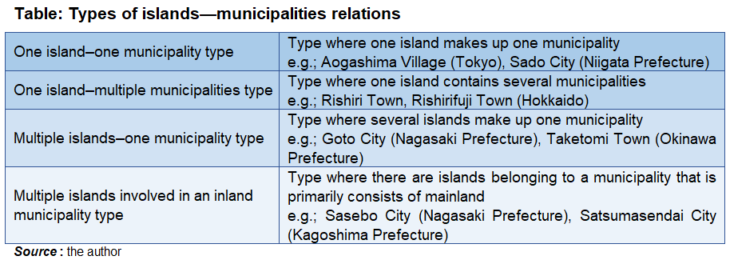

The Table organizes the relationships between island geographic conditions and municipalities to suggest some basic types of island municipalities. Although I call them all island municipalities, their realities are diverse and their challenges for autonomy and administration differ. The following is a discussion of the challenges and prospects for autonomy and administration based on that typology.

(2) One island–one municipality type

The one island–one municipality type is what easily comes to mind when we generally think of “island” as it refers to one island making up one municipality. These municipalities are separated from others by waters and easily cultivate thick relations between people as well as develop unique culture and tradition. These characteristics make such islands good fields for research in folklore and cultural anthropology. Tsujiyama Takanobu argues that, “In order to develop autonomy while making use of the special features of islands, there needs to be an autonomy system that respects the culture and values of the ‘island societies’ that make up a unique life system colored by thick human society,”[4] and if we look at this as the unit of the municipality, this is the type that most easily forms that kind of thick human relations.

From an administrative viewpoint, municipalities that belong to this type are likely difficult to develop close cooperation and associated initiatives with neighboring municipalities due to the state of communications between islands. At the same time, in my own hearing surveys at Hachijo Town and Aogashima Village,[5] Tokyo, I was able to observe diverse wider-area cooperation, both formal and informal. Examples of formal cooperation exist with the Tokyo Island Municipalities Partial-Affairs Association and the Tokyo Municipalities Synthetic Office Work Association as they conduct facility management, joint research surveys related to local revitalization, and joint relatively standard work, such as staff training.

Moreover, there are 20 village officials in Aogashima Village, which has a population of 170. Each handles tasks in a variety of areas. Because of this, whenever village officials are not able to attend national and metropolitan training and briefings that are held whenever individual laws and tax regulations are changed, and they have trouble deciding what to do in daily work at the office because of a lack of precedents, they make inquiries or otherwise obtain information from their nearest neighbor in Hachijo Town.

In this way, even if cooperation between municipalities is generally difficult for this type, such cooperation is nonetheless conducted, either formally or informally, in order to meet residents’ administrative needs through various methods.

(3) One island–multiple municipalities type

The one island-multiple municipalities type is one island with several municipalities. It differs from the one island–one municipality type in that at least one municipality is connected with the mainland, which increases the possibilities of mutual physical cooperation. At the same time, the number of island municipalities of this type is going down with the “great merger of municipalities in the Heisei period” (hereinafter, the “great merger of Heisei”). For example, Sado City (Niigata Prefecture) was born in 2004 with the merging of one city, seven towns, and two villages.

This “great merger of Heisei” has created many “cities” in island areas. Examples of this are Sado City as well as Etajima City (Hiroshima Prefecture), Tsushima City, Iki City (Nagasaki Prefecture), and Amami City (Kagoshima Prefecture). These mergers were conducted to balance pressure for municipal mergers with the continuance of municipalities that remain close to the residents, bringing together areas that to some extent share local issues, whose limits are easy to explain, and where improved sightseeing and traffic convenience can be expected.

Even today, we have examples of the one island–multiple municipalities types in Rishiri Island (Rishiri Town, Rishirifuji Town in Hokkaido), Shodoshima Island (Shodoshima Town, Tonosho Town in Kagawa Prefecture), and Tanegashima Island (Nishinoomote City, Nakatane Town, Minamitane Town in Kagoshima Prefecture).[6] All of these areas have flourishing industries that are very characteristic, like agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and tourism, and are municipalities with different local attributes even on the same island, which is likely why they decided against merging.

(4) The multiple islands–one municipality type

The multiple islands–one municipality type means several islands making up one municipality. Municipalities that are of this type include Niijima Village (Tokyo), Goto City (Nagasaki Prefecture), and Taketomi Town (Okinawa Prefecture). Unlike the one island–multiple municipalities type or the multiple islands–one municipality type, this type is characterized by municipalities consisting of several areas separated by water.

This sometimes makes it difficult to build consensus within the municipality. Taketomi Town, which consists of several islands, was long unable to decide where to place the town office.[7] The town hall for Taketomi Town was in neighboring Ishigaki City, but there were discussions about moving it into the town as a way to foster more unity among residents, enhance the capabilities for disaster prevention and risk management, and vitalize the local economy.[8]

At the same time, public transportation infrastructure was not necessarily sufficient within Taketomi Town, so you basically had to go via the terminal in Ishigaki City when moving between the islands. Taketomi Town consists of nine inhabited islands and seven uninhabited islands, with the most populous island of Iriomote Island (population 2,455) having about 190 times more people than the least populous island of Aragusuku Island (Kamiji and Shimoji islets, population 13) as of the end of April 2021. This made it highly likely that any popular vote would move the town office to Iriomote Island, but Taketomi Town sought to build consensus through repeated deliberations by the assembly, surveys about town office and branch office usage, on-site surveys of candidate locations, multiple local information sessions, and numerous deliberation meetings.

As a result, the town office was moved to Iriomote Island, but the “basic policy on the new Taketomi Town Office” specified that branch offices would be opened in Ishigaki City as well as on the other islands. In addition to this, each island would be assigned a local official and a transportation network would be made to increase convenience, thus showing consideration to gain resident approval.

In the case of Taketomi Town, the facility that is the town office became subject to a kind of consensus building that took the form of what may be termed a “scramble,” but so-called troublesome facilities like waste disposal sites and crematoriums can instead become subject to “imposition.” Unlike areas connected to the mainland, when it comes to the multiple islands–one municipality type, one island having facilities that are very beneficial there may cause inconvenience for the residents of other islands.

Moreover, if troublesome facilities are located on one island, that may allow other islands to benefit from those facilities while minimizing risk in terms of the natural environment, living environment, and tourism image (the so-called Not-In-My-Back-Yard [NIMBY] problems). It can be said that municipalities of the multiple islands–one municipality type easily face challenges of local consensus building for important policy issues.

(5) The multiple islands involved in a mainland municipality type

The multiple islands involved in a mainland municipality type includes municipalities whose central part is on the mainland and that also has islands. More to the point, these are municipalities that have islands within their bounds but where municipal and town offices are not located on those islands.

When discussing the features of the one island–multiple municipalities type, I mentioned the changing numbers due to the “great merger of Heisei,” but one characteristic of the multiple islands involved in a mainland municipality type is that they increased in number during the same period. Examples include Himeji City, Hyogo Prefecture (Ieshima Islands), Saikai City, Nagasaki Prefecture (part of Matsushima, Satsumasendai Island), and Satsumasendai City, Kagoshima Prefecture (Iijima). Moreover, although not directly related to the “great merger of Heisei,” the exceptional case of Omihachiman City including Oki Island in Lake Biwa also belongs to this type.

This multiple islands involved in a mainland municipality type can also be organized smaller in connection with municipal mergers. First, we have cases where existing large cities merge with former island municipalities, such as the merger of former Himeji City with a population of about 480,000 with former Ieshima Town (island municipality of the multiple islands–one municipality type) with a population of about 7,600. In such cases, the former island municipality decided to merge with a big city because of concerns about the municipality’s finances and local economy and demographics.

Secondly, we have mergers of municipalities of relatively equal population size, such as Saikai City. In the case of Saikai City, there was no great difference in population between the biggest former Seihi Town (population about 10,000) and the smallest former Sakito Town (population about 2,300), so we can differentiate this from the aforementioned Himeji City merger. The Saikai City merger involved a total of five towns in the Nishisonogi District, excluding two of the towns with relatively large populations and stable finances, so a strong feature here was size “equality.”

With the Himeji City type, former Himeji City was expected to bring stable administrative and financial ability, but there can also arise the question of how the opinions of the residents of the former island municipalities, with such relatively small populations, would be reflected in decision-making in the new city. When it comes to this issue, points that can be made about any medium- or small-sized municipalities merging with a big city, not just island municipalities, risk becoming more serious for islands because of physical distance and communications.

With the Saikai City type, municipalities might not have any problem projecting their presence in the new city, but depending on the administrative and financial ability of the new city, there might be little actual effect from the municipal merger.

With regard to the multiple islands involved in a mainland municipality type, it is necessary to reflect residents’ views in policy through representatives of former island municipalities in the assembly and otherwise to develop and use mechanisms to distribute powers within the city (or area). It goes without saying that it is also important to solve local problems through the autonomous activities of local communities.

(6) Island municipalities with complex elements

Figure. Hirado City zones

So far, I have discussed four types of island municipalities and identified the features and challenges of autonomy and administration in those respective cases, but this has only been a basic discussion. In reality, there exist island municipalities with complex elements. For example, Hirado City (Nagasaki Prefecture) was a city centering on Hirado Island since before the “great merger of Heisei,” and we also had Takushima Island, which was a multiple islands–one municipality type that included Takashima Island. However, when Hirado Bridge was completed in 1977, it became possible to travel on land from Hirado Island to mainland Kyushu.[9] Furthermore, when Ikitsuki Bridge was completed in 1991, it became possible to travel on land between Ikitsuki Island (former Ikitsuki Town) and Hirado Island.

When Hirado City was created through a merger of Hirado City, Tabira Town, Ikitsuki Town, and Oshima Village in 2005, it came to possess features of the multiple islands–one municipality type while also including parts of mainland Kyushu through the connection with Hirado Island, which was the center of the city’s administration and economy. In a municipality like Hirado City, the bridges have resolved some of the inconveniences in communications, but the need for careful consensus building within the city remains. In this way, there are extremely diverse ways that the geographic conditions of islands can relate to municipalities as administrative subjects.

Prospects for the autonomy and administration of islands

(1) The need for a flexible system of local autonomy

Based on the discussion above, I want to think a bit about autonomy and administration in island municipalities in the future.

Firstly, there is a need for a local autonomy system that suits the local area’s actual conditions. As islands possess diverse local attributes, they are especially ill-suited for nationwide uniform institutions and policies, which make it difficult to achieve their various intentions and goals.

As mentioned previously, the local government system of the Meiji period placed island municipalities outside the nationwide system, which in this sense made them “special” entities, but this only meant lack of uniformity as the island municipalities were simply granted a local government system that stipulated centralized and circumscribed autonomy.

Then again, realizing institutions and policies rooted in the local area does not necessarily mean that islands have to be treated as special. In other words, what is needed is increased flexibility in the local autonomy system as a whole, thus facilitating decision-making, consensus building, and policy implementation that accommodates local characteristics and circumstances.

(2) The need to design systems with island municipalities at the center

Furthermore, we need to design various systems with municipalities at the center. What I mean by systems here is not just systems to do with local autonomy but policy systems that extend over many areas, including remote islands development, measures again population decline, medicine/welfare, education, transportation, local economy, and disaster prevention/crisis management.

The Remote Islands Development Act system today has been decentralized but the work is largely in the hands of the prefectures.[10] Yet there is no reason why only prefectures should play a central role. It is true that “remote islands development measures areas” as defined by the Remote Islands Development Act include some island areas that cover several municipalities, but there are also many cases where a single municipality or only part of it is designated. Moreover, even if the area designated covers several municipalities, there should be guaranteed scope for administrative work through horizontal coordination and cooperation between municipalities based on the “principle of subsidiarity.” Seen from this perspective, there appears to be no reason why the local autonomy system should prevent municipalities from taking a central role in remote islands development in the future.

At the same time, even if island municipalities are allowed to take a central role in institutions and policies, this will be of no practical importance if they lack the funds to back up their activities.

One reason for the “great merger of Heisei” was to enhance the administrative and fiscal foundations of municipalities, but previous studies have shown that municipal mergers do not necessarily improve the financial ability of municipalities or act as a proper brake on population decline.[11] Since changes to island municipalities’ type due to mergers may lead to concomitant challenges, we ought to be careful about trying to enhance administrative and fiscal foundations through municipal mergers, especially for island municipalities.

Other methods to enhance administrative and fiscal foundations besides municipal mergers include approaches like environmental beautification, environmental conservation, and maintenance/development of tourism facilities in several municipalities in Okinawa Prefecture, for which environmental cooperation taxes have been created as a type of informal taxation to cover the costs. Additionally, some town charge entrance fees (island entrance fees) as an alternative to taxation. In this way, some island municipalities are actively working to secure funds, but some also argue for the need to secure sources of funds that support the building of environments for permanent residency and exchanges.[12]

Thus, there is a need to secure sources of funds to create systems that allow island municipalities to conduct activities independently and make them substantive.

(3) The need for arrangements to distribute power and build consensus within municipalities

I have already mentioned that island municipalities that possess elements of the multiple islands–one municipality type and the multiple islands involved in a mainland municipality type run a risk of struggling with consensus building and decision-making within the municipality. It is not unusual for these island municipalities to deal with this through their own unique initiatives.

First, looking at the various islands, we may assume that they need political action to send representatives to municipal assemblies. The municipal assembly really should not simply be a site of majority decisions but a place where the municipality makes decisions through careful deliberation. With this in mind, it should be deeply meaningful to bring in diverse local voices into the assembly.

Moreover, it is very necessary to develop neighborhood governance, thereby making it possible to better reflect the voices of residents in policies.[13] Important here is not only the institutional development of the local authorities but also the activities of residents and local communities. Residents and local authorities will need to work together to create arrangements that accommodate local features while also referencing existing cases.

Conclusion

For an island country like Japan, the geographic conditions of islands tend to garner interest from the central government from the perspective of diplomacy and security. With the movement for the creation of the Remote Islands Development Act, emphasis on the national significance of islands made it possible to successfully secure financial support from the central government to prefectures and municipalities with islands. Meanwhile, if there is disagreement between the intentions of island municipalities with unstable administrative and financial ability and the central government, it might become difficult for the former to exercise their autonomy. Of course, although this paper focuses on island municipalities, Japan is a two-layered local autonomy system, so we should also pay attention to the functions played by prefectures, which exist in-between the national government and the municipalities. Under the current Remote Islands Development Act system, prefectures sometimes play a central role, so it is necessary to consider the autonomy and administration of island areas with reference to the government system of national government—prefectural governments—municipal governments (basic municipality).

I have already mentioned that when considering the autonomy and administration of island areas as well as remote islands development, it is necessary to clarify the respective roles of the national government, the prefectural governments, and the island municipal governments and design a system that centers around island municipalities. In this regard, I believe municipalities as prefectures must consider their own measures based on an understanding of how issues are perceived in municipalities, which are the closest to the lives of residents.

From a perspective of regional development, islands are considered so-called “disadvantaged areas,” but harsh conditions necessitate special ways of approaching various processes, such as the discovery and grasping of challenges, the consideration of necessary policies, consensus building, and how to implement policies. The idea of dividing powers within cities may be considered an example of institutionalizing such processes. In this sense, island municipalities have the potential of transforming themselves from being advanced problem areas to being advanced problem-solving areas by themselves creating and operating the tools needed to advance autonomy while refining them.

Translated from “Tokushu 2 ― Toshochiiki no korekara: Toshochiiki ni okeru Jichi to Gyosei (Special Feature 2— The Future of Island Areas: Autonomy and Administration in Island Areas),” THE TOSHI MONDAI (Municipal Problems), July 2021, pp. 47–55. (Courtesy of The Tokyo Institute for Municipal Research) [September 2021]

[1] For more details, see Takaesu Masaya (2009), Modern Japanese Local Governance and the “Islands,” Yumani Shobo.

[2] For more about Yamagata Aritomo’s views on the state, see Inoue Toshikazu (2010), Yamagata Aritomo and the Meiji State, NHK Publishing.

[3] Furthermore, there existed a system that limited the suffrage of island residents in connection with the Public Office Election Law also in the postwar period. For more details about this and other legal systems affecting islands and how they were operated, see Enosawa Yukihiro (2018), Remote Islands and the Law: Thinking about Constitutional Issues from the Izu and Ogasawara Islands, Horitsu Bunka Sha.

[4] For more details, see Tsujiyama Takanobu (2021), “Toward Establishing Autonomy that Makes Use of the Bonds of Island Society,” 57.4, pp.50-57.

[5] With research aid from the Meiji University Graduate School “2019 Graduate Student Research and Survey Program,” I visited and conducted hearing surveys at both Hachijo Town (February 6, 2020) and Aogashima Village (February 10, 2020). When conducting these surveys, I received the help of the Center for Research and Promotion of Japanese Islands. The accounts here are part of the results of those surveys. I wish to express my gratitude to everyone who assisted me.

[6] Of these, Tonosho Town has the character of the multiple islands-one municipality type as it includes Okinoshima, Odeshima, and Teshima islands.

[7] For more on this case, see Kuroishi Keita (2017), “Initiatives and Challenges in Consensus Building in Municipalities Made up of Several Islands: The Case of the Move of Taketomi Town Office,” Seiji keizaigaku kenkyu ronshu (Journal of Economics), 2, pp.59-77.

[8] Meanwhile, on Iriomote Island, which was the most likely candidate for having the office, there were those who worried that the move might impact the natural environment.

[9] With Notification of Prime Minister’s Office No. 33 (October 18, 1978), Hirado Island stopped being a remote islands development measures area. Meanwhile, Hirado City was designated a peninsula promotion measures area in accordance with the Peninsula Promotion Act for being part of the Kitamatsuura Peninsula (excluding remote islands development measures areas).

[10] The reason for the central role played by the prefecture in the current Remote Islands Development Act system is that the Remote Islands Development Act itself is a result of actions by prefectures (governors). For more about the formulation of the Remote Islands Development Act, see 30 Years of Remote Islands Development Editing Board (1989), “30 Years of Remote Islands Development, Volume 1: The Course of Remote Islands Development,” National Remote Island Promotion Council.

[11] For more details, see Koizumi Kazushige (2020), “Accelerated Population Decrease and Aging in Former Municipalities: Examining the Heisei Mergers,” Jiji jitsumu semina (Autonomy Practical Seminar), 692, pp.54-58. This paper compares former municipalities that underwent municipal mergers during the “great merger of municipalities in the Heisei era” period with neighboring municipalities with similar attributes, looking at demographics and rate of population aging. With regard to island municipalities, Ojika Town and former Uku Town in Nagasaki Prefecture (currently Uku Town, Sasebo City) are compared to show that both post-merger rate of population decline and rate of population aging were lower in Ojika Town, which did not merge. In addition, municipal mergers of islands area are discussed in Research Division of the Tokyo Institute for Municipal Research (2012), “Remote Islands and Mergers,” Toshi mondai (Municipal Problems), 103(8), pp.84-93, among others.

[12] For more details, see Numao Namiko (2012), “Securing Sources of Funds that Support the Building of Environments for Permanent Residence and Exchanges,” Kikan shima (Quarterly Islands), 57(4), pp.42-49.

[13] For more details about basic ideas and cases on power distribution in cities, see Japan Municipal Research Center, ed. (2016), Building a Future of Power Distribution in Cities: Many-Sided Study Based on a National Municipal Questionnaire and Case Survey.

Keywords

- Kuroishi Keita

- Japan Municipal Research Center

- island areas

- island municipalities

- types of islands

- autonomy

- administration

- municipal mergers

- great merger of municipalities in the Heisei era

- 424 public medical institutions list

- Local Autonomy Act

- Remote Islands Development Act

- Yamagata Aritomo

- One island–one municipality

- One island–multiple municipalities

- multiple islands–one municipality

- multiple islands involved in a mainland municipality

- regional development

- disadvantaged areas