The “non” constitutional Japanese: What Needs to Be Done to Avoid a Dead Constitution

Sakaiya Shiro, Professor, Faculty of Law and Graduate Schools for Law and Politics,

University of Tokyo

Going beyond “constitutional revision vs constitution protection”

Prof. Sakaiya Shiro

When categorizing the two sides of Japanese ideas about the Constitution, the long-lived postwar standard has been kaikenha (constitutional revisionists) or gokenha (constitutional protectors). This categorization almost perfectly corresponds to the ideological right wing and left wing or what was termed “conservatives” and “progressives” in the terminology of postwar politics.[1] It goes without saying that this opposition is about the legitimacy of the “imposed constitution” that was enacted under the strong influence of the Allied Occupation [1945-52] GHQ (General Headquarters of the Allied Forces) and how to appraise its contents (especially Article 9).

However, I suspect the constitution views of the Japanese today have a fundamental aspect that needs to be addressed before we talk about the merits and demerits of constitutional revision. It is the question of “how constitutional” the Japanese (how much we understand and espouse the ideas of constitutionalism) are.

I will cite an orthodox explanation of constitutionalism and the modern constitution based on it from a textbook on constitutional law.

“The idea known as modern constitutionalism sees the state’s mission as ensuring individual rights and freedoms, but assumes a position of having to protect rights and freedoms from the state itself as it possesses immense power for the fulfillment of that mission, seeking to strictly limit the actions of state agencies to achieve that aim. A constitution that is based on such thinking is called a Constitution of constitutional meaning or a Constitution in the modern sense.” (Hasebe Yasuo, Constitution (Seventh Edition) (Shinseisha 2018, pp. 10-11)

Such constitutional thought is intimately connected with the principle of “rule of law,” which “aims to protect the people’s rights and freedoms by restricting power through law” (Ashibe Nobuyoshi, Constitution (Seventh Edition) (Iwanami Shoten 2019, pp. 13-14).

In this paper, I refer to those who understand the ideas of constitutionalism and recognize its normativity as “constitutionalists,” while I refer to others as “non-constitutionalists.”

In postwar Japan, constitutionalists were in reality often identified as constitutional protectors and non-constitutionalists as constitutional revisionists. It seems that this trend has intensified further in recent years as the leading opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ), has adopted a passive stance on constitutional revision.

However, the twin categorizations of “constitution protection/constitutional revision” and “constitutionalism/non-constitutionalism” are not principally the same.

It is of course possible to be a constitutional revisionist who espouses constitutionalism. It is impossible to consider all kinds of substantive constitutional changes, which are common in other countries, as unconstitutional behavior.

Conversely, it is also entirely possible for non-constitutionalists to be constitutional protectors in a passive sense (not actively recognizing the need for constitutional revision). What non-constitutionalists reject or dismiss is not the text of the current constitution but the functions of the modern constitution itself. To begin with, it is rather unnatural for someone who does not recognize (or understand) the raison d’être of the Constitution to have a strong motivation to revise concrete contents.

The thing is, constitution protection and constitutionalism, constitutional revision and non-constitutionalism are ways of thinking or positions independent of each other. It follows that distinction is needed when analyzing voters’ Constitution views.

As such, this paper will empirically examine how constitutional the Japanese are today and what differences exist between constitutionalists and non-constitutionalists in terms of social attributes and other aspects of political attitudes. There have been few attempts at analyzing the awareness of general voters from this perspective. The reason for this is that the ideological perspective of whether the Constitution should be revised has monopolized the viewpoints of conventional Constitutional debates.

Measuring Constitution views

The analysis in this paper is based on online survey results I gathered in January 2021.[2] The survey was of the registered monitors of a market research firm, Rakuten Insight, with allotment of residence (prefecture), sex, and age according to actual population ratio. The total number of respondents was 4,000.

The focus of the questions in the survey was “What is closer to your image of how the Constitution ought to be?” I provided A and B as two opposite “images” of how the Constitution ought to be. The respondents were asked to choose one of “Close to A (B),” “Closer to A (B) than to B (A),” and “Neither.” The following are the concrete texts for A and B.

A: After all, the Constitution represents the ideal form of the state, so the government should decide on policy flexibly as reality demands, without being hung up on the words of the Constitution.

B: The Constitution is concrete rules that restrict state power, so the government should not adopt policy that is not allowed by the text of the Constitution even when reality demands it.

I created this question with inspiration from the debate between Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and the opposition party in early 2018. In January of the same year, Prime Minister Abe said that the Constitution “describes the national framework and ideal nation,” in response to which the Leader of the Democratic Party, Edano Yukio criticized it as “a peculiar viewpoint,” saying that “the definition of the Constitution is […] rules by which the sovereigns restrict political power.”[3] These two views are contradictory, so that in Edano’s view, Abe who lacks the latter constitution views ends up dismissing constitutionalism.

Images A, B attempted to capture this opposition over constitution views more clearly. In A, the government’s actions are actually not restricted by the Constitution. Those who choose A are likely to see the role of the Constitution as a moral goal of policymakers, as in the “Seventeen-Article Constitution” [promulgated by Prince Shotoku (574–622) in 604], which is famous for the line “Harmony is the greatest of virtues…” This is not a modern constitutionalist way of thinking (the Seventeen-Article Constitution obviously is not a modern constitution).

Constitutionalists who value the rule of law must pick B when choosing from the two images. Or rather, thinking of the Constitution’s role as B (not thinking it is like A) is the definition (at least partly) of constitutionalism.

The many non-constitutionalists

So, which of A and B were the constitution views of the 4,000 people closer to?

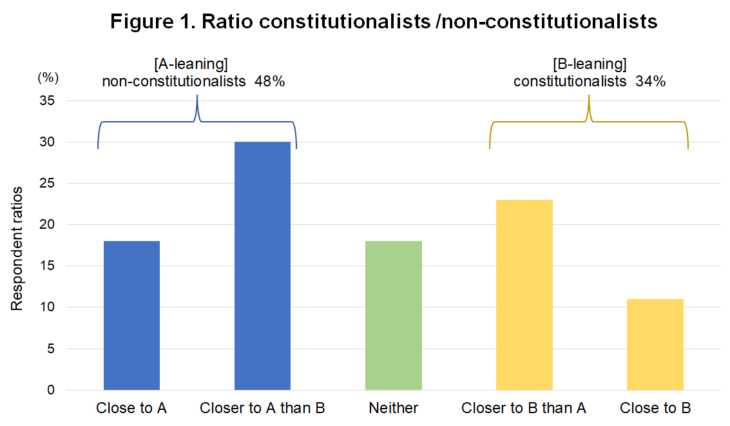

Figure 1 shows the total response results. If “Close to A (B)” and “Closer to A (B) than to B (A)” are bundled as “A-leaning (B-leaning),” “A-leaning” gets a total of 48% and “B-leaning” a total of 34%. In other words, if you simply classify “A-leaning” as non-constitutionalists and “B-leaning” as constitutionalists, non-constitutionalists are clearly dominant.

Only 11% of the respondents were strict constitutionalists who chose “Close to B.” In other words, 89% to some extent think that the government should implement “policy that is not allowed by the text of the Constitution” at least sometimes. They are saying that it is okay to (flexibly?) allow unconstitutional legislation depending on the situation.

This survey is not a random sample, so we cannot directly infer how many Japanese are constitutional. However, unless the monitors registered for the online survey are significantly non-constitutional compared to those who do not register (there is no evidence for this at all), then I have to admit that there is a large number of non-constitutionalists in Japanese society today.

These survey results were very shocking to me who studied at a faculty of law (and teaches at a faculty of law) and those around me. I conducted the survey suspecting that there might be quite a few “A-leaning,” but I did not expect them to be a majority at all. With this many “A-leaning,” I cannot help but wonder how much my readers will be able to share the surprise we felt.[4]

Furthermore, I want to cite one existing public opinion poll using a random sample to corroborate that the results of my survey were not entirely off mark.[5]

A survey conducted by the Yomiuri shimbun newspaper in March–April 2018 asked, “What is closer to your image of how the Constitution ought to be?” with the options “(A) It shows the shape and ideal of the state” and “(B) Rules that limit state power.” The results were 60% for A and 37% for B. Looking back on the Edano discussion I mentioned earlier, it is likely that the majority of voters and not just Prime Minister Abe do not understand the “definition of Constitution.”[6]

The concept and idea of constitutionalism is taught throughout compulsory education today. However, it is far from having become part of the Japanese consciousness at all. It has long been pointed out that many people are not familiar with the specifics of the Constitution (that is true). However, I have to say that the problem lies on a more fundamental level for a lot of Japanese.

Who is (non-)constitutional?

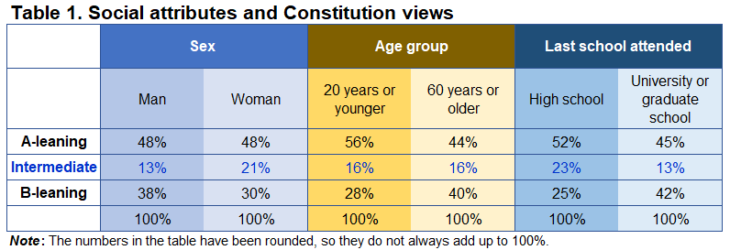

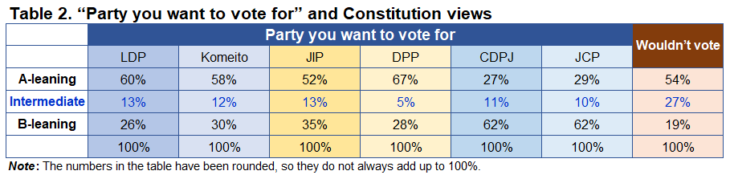

Constitutionalists and non-constitutionalists are not evenly distributed across the population. Voters with certain social attributes are more (non-)constitutional than others. This is shown in Table 1, which looks at differences in constitution views according to sex, age group, and education (to simplify the discussion, I only included the age groups “20 years or younger” and “60 years or older” and the education categories “High school” and “University or graduate school”).

The table shows that younger persons with lower education are relatively more “A-leaning,” meaning that they tend strongly toward non-constitutionalism. There is no considerable difference between men and women, but many women are “Intermediate” (Neither), with few being “B-leaning” constitutionalists.

Next, Table 2 looks at responses by supporting party (party you want to vote for), indicating that many Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Komeito, Japan Innovation Party (JIP), and Democratic Party for the People (DPP) supporters are “A-leaning,” while many CDPJ and Japanese Communist Party (JCP) supporters are “B-leaning.” We may conclude that those who are ideologically centrist or right wing (the conservatives) have a strong tendency toward non-constitutionalism. However, we need to take note that there are quite a few non-constitutionalists (27%) even among CDPJ supporters.

Table 2 also shows that relatively many in the group who “Wouldn’t vote” are “A-leaning.” This results suggests that people with little interest in politics tend toward non-constitutionalism.

The relationship between constitutionalism and opinion on constitutional revision

Lastly, let us take a look at the relationship between constitutionalism and opinions on constitutional revision. Of course, there is the serious question of whether there is any point in asking about the right or wrong of constitutional revision to someone without an understanding of constitutional function, but this has always been done in public opinion polls.

In this survey I asked about the right or wrong of constitutional revision in quite some detail. I provided the text of the current Article 9 in its entirety and asked, “Do you agree or disagree about a constitutional revision that deletes Paragraph 2 from here and adds the following?” “The following” refers to the “Article 9-2” proposal that is part of the “Current Status of Constitutional Discussion” presented by the LDP in 2018, so I provided the respondents with a concrete article proposal that specifies the existences of the Self-Defense Forces (SDFs).[7] It was a simulation of a national referendum for constitutional revision.

“Article 9-2” proposal

Article 9-2 The prescriptions of the preceding article do not preclude self-defense measures needed to protect Japan’s peace and independence or maintain the safety of the state and the people, so the SDF will exist as an effective organization for those purposes, having as its highest commander the Prime Minister, who is the head of the Cabinet, in accordance with the law.

② The actions of the SDF will require the approval of the National Diet and other controls in accordance with the law.

(*Added to Article 9, whose text is preserved in its entirety)

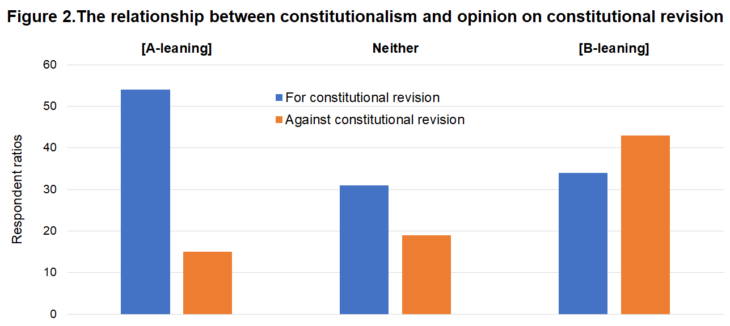

Figure 2 shows the responses, tallied by views on constitutionalism (to simplify the discussion, I do not include the intermediate response “Doesn’t matter if revised or not”). According to this, the vast majority of non-constitutionalists (A-leaning) support constitutional revision. By contrast, many constitutionalists (B-leaning) support constitution protection. Especially the group of strict constitutionalists who answered “Close to B” had an almost double score with 30% constitutional revision and 59% constitution protection.

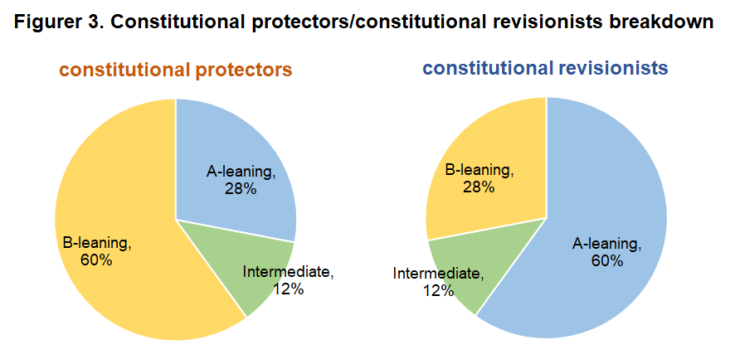

In connection with this, Figure 3 shows a breakdown of constitutional protectors and constitutional revisionists, indicating a striking contrast. While 60% of constitutional protectors are constitutionalists (B-leaning), 60% of constitutional revisionists are non-constitutionalists (A-leaning). In the beginning, I pointed out that constitutional protectors and constitutionalists as well as constitutional revisionists and non-constitutionalists tend to be considered the same, which is actually somewhat supported when we look at the reality.

In short, if we look at Japanese constitutional politics, there is a cleavage mainly between the positions of “constitution protection of constitutionalism” and “constitutional revision of non-constitutionalism” on the voter level. It is a twisted conflict where those who think that the Constitution restricts government action do not care for substantive constitutional changes (for some reason),[8] while those who do not think the government has to care about the Constitution do want substantive constitutional changes (for some reason).

Meanwhile, the correspondence between constitutionalism and the opinions of constitution protection is not perfect (this is why I set up a constitutionalism/non-constitutionalism axis in addition to a constitution protection/constitutional revision axis). “Constitutional revision of the constitution” is a position exemplified in political circles by Yamao Shiori (who wrote Rikkenteki kaiken [Constitutional revision of the constitutionalism] [she retired from political life without running for the 2021 Lower House election and is now acting as a lawyer under her real name, Kanno Shiori]), but also exist to some extent among the respondents (12% of the total). This position argues that properly positioning the SDF in the Constitution and having it regulated through this will make the Japanese polity more constitutional or finally make it constitutional.

Moreover, “constitutional revision of non-constitutionalism” supporters are few but exist as well (7%). They argue that constitutional revision is not needed as they do not put much emphasis on the Constitution itself, so this position should be considered passive constitution protection. This group can become (have become) powerful support for elites who wish to stop constitutional revision, but they likely are not so attached to the current Constitution.

For the rehabilitation of constitutionalism

In this paper, I started from a position of emphasizing the distinction between constitution protection/constitutional revision and constitutionalism/non-constitutionalism to empirically investigate the constitution views of Japanese people. The results provided a number of insights, but the most important is that constitutionalism is not firmly established among the Japanese. I have noted this in previous public opinion polls as well,[9] but it was confirmed with our survey this time.

In Japan, most voters think that “the government should decide on policy flexibly as reality demands, without being hung up on the words of the Constitution.” As long as the government can convince voters that “reality demands it,” it can implement policy that goes against the Constitution (rather, that is what society wants).

It is not a preposterous assumption that society approves of “unconstitutional legislation” by the government. In fact, looking at defense policies in the postwar period, the government has repeatedly devised and implemented policies that many constitutional scholars have deemed unconstitutional. The 1950s substantial rearmament itself (the argument that the SDF is unconstitutional was very potent in the 1955 System [the ideological confrontation between the LDP and the Japan Socialist Party] period at least) and in recent years the Legislation for Peace and Security that allows the right of collective self-defense have come about despite the doubts expressed by many constitutional scholars. Such policies that (are strongly suspected to) deviate from the Constitution were considered fairly problematic among voters in the beginning but were accepted as time went by.[10] In this way, although no part of the text in Article 9 has changed, the range of SDF activities keeps expanding gradually.

What I want to discuss here is not the pros and cons of currently adopted defense policies. The issue is that “constitutionalism cannot be considered to be firmly established […] in case policymakers want to flexibly implement constitutional revisions or ‘reinterpret the constitution’ according to what is best at the time.”[11] That is, we really must question the process of postwar politics whereby the elites (politicians and intellectuals) and ordinary voters have worked together to destroy constitutionalism or rendered the Constitution meaningless.

As someone who values liberal democracy, I have to say that the most pressing concern is to establish constitutionalism among the people, rather than to talk about ideological constitution protection theory/constitutional revision theory. In other words, we ought to discuss the question of whether to conduct constitutional revision from the viewpoint of whether to establish constitutionalism, not only whether to abolish pacifism.

The results of this paper’s analysis of the relationship between education and constitutional views suggest that school education contributes somewhat to the establishment of constitutionalism. At the same time, there were at least as many non-constitutionalists as there were constitutionalists, even among those going on to university studies.

My view is that the reason for the limitations on internalizing constitutionalism through school education is this principle really cannot be said to be practiced in the real world (at least from the layperson’s perspective). Of course, the biggest issue is the Article 9 issue.

Constitutional scholars also agree that “The Article 9 issue has become the biggest Achilles heel of Japanese constitutionalism since the creation of the SDF” (Takahashi Kazuyuki). Many postwar jurists have “struggled” in their pursuit of a “theory that can explain and offer guidance for the gap between the Constitution and reality.”[12] However, because it has been difficult to gain support for constitution protection of constitutionalism from the ordinary citizens, although elites can justify it through logical acrobatics (in the fashion of Mikkyo [esoteric Buddhism]), we have had the unfortunate result that the Japanese constitutional awareness (the view that “the Constitution is concrete rules that restrict state power”) has been eroded.

I would say that those who can change this situation are the people whom I categorized as constitutional revisionists of the constitution in this paper. However, this position cannot be considered mainstream in Japanese political circles. Rather, constitutional revisionists of the constitution appear to have not existed in the main political parties throughout the postwar period. This is likely the cause and result of the dominance of ideological constitutional theory in postwar politics.

Considering the above, I think the first step to having constitutionalism take root in Japan is to establish an idea of constitutionalism that separates it from the opinion of constitution protection. It needs to be distanced from ideological constitutional theory. This paper should serve as a milestone for that purpose.

Translated from “‘Hi’ Rikkentekina Nihonjin: Kenpo no shi-bunka wo tomerutameni subekikoto (The “non” constitutional Japanese: What Needs to Be Done to Avoid a Dead Constitution),” Chuokoron, December 2021, pp. 94-103 (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [January 2022]

[1] In the early postwar period, the abolition of the Emperor system and other expressions of left-wing constitutional revision argument were also advocated somewhat prominently. For example, about how the Japanese Communist Party initially rejected the contents of the new [current] Constitution head-on, see Sakaiya Shiro, Kenpo to Yoron—Sengo Nihonjin wa kenpo to do mukiattekita noka (Constitution and public opinion—How have the Japanese faced the Constitution after the WWII?), Chikuma Sensho 2017, Chapter 2.

[2] This research received assistance from Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) 20K01479 and was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University of Tokyo.

[3] Plenary session of the House of Representatives held on January 24, 2018.

[4] For reference, when I asked this question to 17 students (Faculty of Law at the University of Tokyo), the result was 1 person answering “Close to A,” 3 people “Closer to A than B,” 8 people “Closer to B than A,” and 5 people “Close to B.” 24% were “A-leaning” and 76% “B-leaning.” Although it is only a reference value because the number of cases is small, I would like to note that the number of “B-leaning” was overwhelmingly large in a group considered to have the highest legal literacy in Japanese society.

[5] For other public opinion polls showing that many Japanese are non-constitutionalists, see Sakaiya Shiro, “Nihonjin no Kenpokan (Constitution views of Japan),” Horitsu-Jiho Vol. 90, No. 9 2018, pp. 131-135.

[6]Yomiuri shimbun dated April 30, 2018. This question format is almost the same as mine, which is natural since I used it as a reference. However, the wording I used was more suitable for exposing non-constitutionalists as the contradictory nature of the two images was more readily conveyed to the respondents.

[7] The LDP’s draft constitutional amendment from 2018 actually wanted to “preserve” Article 9, Paragraph 2 while adding Article 9-2. In order to investigate differences in voter responses between “deleting” and “preserving” Paragraph 2, I divided the survey sample into two and prepared two versions of the question, but there was no major difference between the two groups. In this paper, I discuss the agreement and disagreement with deleting Article 9, Paragraph 2, which “constitutional revisionists of the constitution” are thought to favor.

[8] Furthermore, even among “B-leaning” persons, about 90% are neutral or positive (at least 5 points) in their appreciation of the SDF (scale from 0 to 10; higher score indicates more positive). That is, many in this group recognize the existence of the SDF in fact (and largely positively), but are nonetheless passive when it comes to specifying the SDF in the Constitution.

[9] Sakaiya, “Nihonjin no Kenpokan”

[10] For more about the increase in voters who consider the SDF constitutional throughout the postwar period and the 10% decrease in voters who consider the 2015 Legislation for Peace and Security unconstitutional from 2016 to 2017, see Sakaiya Shiro, “Decoding public opinion polls to understand the Japanese people’s fickle attitudes towards the constitution: A look back at the constitutional revision debate and the “Neo 1955 system,” Chuokoron, May 2018, pp. 76-87.

[11] Inoue Tatsuo, Rikkenshugi toiu kuwadate (An attempt of constitutionalism), University of Tokyo Press, 2019, page 138.

[12] Takahashi Kazuyuki, the foreword for the Seventh Edition included in Constitution, Ashibe Nobuyoshi (Iwanami Shoten 2019).

Keywords

- Sakaiya Shiro

- Graduate Schools for Law and Politics

- University of Tokyo

- Constitution

- constitutionalism

- non-constitutionalism

- kaikenha

- constitutional revision

- gokenha

- constitutional protection

- conservatives

- progressives

- Article 9

- Article 9-2

- SDF

- postwar politics

- constitution protection theory

- constitutional revisionists of the constitution

- Yamao (Kanno) Shiori