Land and Homes and the Japanese: The issue of vacant houses and land with unknown owners today—What progress with preparations for closing houses?

Nozawa Chie, Professor, School of Political Science and Economics, Meiji University

Prof. Nozawa Chie

For many years, the dream of owning a plot of land and a home has characterized the Japanese. Nonetheless, we are now faced with a strange situation where the issue of land with unknown owners and the issue of vacant houses is becoming increasingly serious.

The underlying factors for these two issues are identical. Not long ago, the norm was for land and houses to be passed from the older to the younger generation. However, in the context of the population outflow from rural to urban areas and the nuclearization of families, land and houses in hometowns are no longer valuable assets. In addition to deficiencies in the real property registration system, there are cases where people who have left their hometowns do not even realize that they have inheritance rights. This is related to the changing times as well as weakening ties to family and relatives.

However, the issue of vacant houses is focused on residential areas unlike forests, wilderness, agricultural land, or other land with unknown owners. The increase in vacant houses does not only have a major impact on the day-to-day living environment, but also on dwindling populations in regional areas, falling land prices, and decreasing tax revenues.

Toward a New Phase

In addition to this situation, it seems that the issue of vacant houses has entered a new phase with the increasing and intensifying disasters of recent years.

This is due to recent global climate change and the worsening problem of vacant houses in Japan.

For several years now, I nearly always get media requests for interviews about the issue of vacant houses in disaster areas every time a disaster occurs. The reason is the frequent occurrence of situations that endanger the lives of local citizens and their properties when vacant houses are destroyed by typhoons, heavy rains, or earthquakes.

For example, several vacant houses damaged in the 2019 Yamagata earthquake or by Typhoon Faxai, which hit Chiba Prefecture in the same year, suddenly posed a peril, but the houses were not demolished but abandoned due to the economic situation of the owners or unknown owners. As a result, they endanger the local area even after the disasters. When Typhoon Haishen (2020) hit, at least three vacant houses caused secondary damage when they collapsed and destroyed adjacent homes in Kyushu and Yamaguchi Prefecture. When the 2021 Atami landslide hit Shizuoka Prefecture in July that year, the large number of vacant houses, including second homes in the disaster area, caused confusion when confirming the whereabouts of victims as the rescue operations raced against time.

The basis for municipalities to charge owners for the cost of emergency measures is not clearly laid out in the Vacant Houses Special Measures Act. Therefore, another pressing issue that has come to light is that it is difficult for municipalities to respond in a flexible manner at the time of a disaster.

According to research by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, 12.03 million households, or about one in four households, in Japan are located in disaster hazard areas (sediment-related disaster risk areas, tsunami inundation areas, or inundation areas).

Amid the increasing and intensifying disasters, there is a pressing need to put countermeasures in place, including identifying vacant houses by listing ownership information during normal times and incorporating information about vacant houses in local disaster management plans and disaster prevention action plans with a focus on hazard areas.

Japan’s Housing Policies: Consistent Support for Housing Construction

Looking back at the history of housing policies in Japan, before the war, the ratio of rental houses in Tokyo was approximately 70% with home owners in the minority. However, the city faced an overwhelming housing shortage during the high economic growth period (1955–1972) when large numbers of people moved from the countryside to the burnt-out city. The state promoted a policy of house ownership and supported a housing construction boom by setting up the Government Housing Loan Corporation (currently Japan Housing Finance Agency) in 1950 to avail ordinary people of mortgages.

Since land prices in urban centers rose steeply from the period of high economic growth to the bubble economy (1986–1991), ordinary people moved to suburban areas in the search for homes at affordable prices. After the bubble burst, deregulation was introduced as one of the economic measures for addressing the problems of falling land prices and nonperforming loans. For example, the Building Standards Act and the City Planning Act were amended to facilitate construction of large-scale housing. The Act on Special Measures concerning Urban Reconstruction took effect in 2002. This led to special urban renaissance districts, which were exempt from existing regulations of building in areas for city planning facilities, being established in urgent urban regeneration areas in ordinance-designated cities. As a result of such large-scale deregulation, floor area ratio and other forms of deregulation also progressed with the aim of promoting urban residences and urban redevelopment projects, leading to an abundance of high-rise condominiums. Meanwhile, the development criteria for controlled urbanization areas on farmland on the outskirts of large cities were relaxed and urban areas spread out in a chaotic fashion. According to the Housing and Land Survey by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC), the result was that the total number of houses exceeded total households by 16% in 2018.

The Aftermath of the High Economic Growth Period

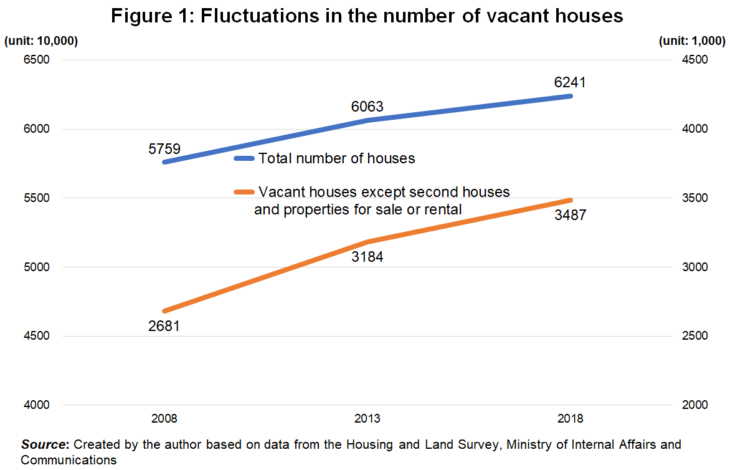

Between 2008 and 2018, the total number of houses increased from 57.59 million to 62.41 million, which is an annual average increase of approximately 480,000 houses. Meanwhile, the number of vacant houses, except houses for sale, for rent, or second homes, rose from 2.68 million to 3.49 million in the same period, posting an annual increase of approximately 80,000. (Fig. 1)

In addition, there is potential for large numbers of vacant houses in the near future. According to the Housing and Land Survey (2018), there are as many as 8.29 million detached houses with elderly residents, in other words, potential vacant houses. It is increasingly likely that the increase in the volume of vacant houses will accelerate as we approach the era of massive inheritance when not only baby boomers (born 1947–49), but also the children of baby boomers (born 1971–1975) will simultaneously inherit their parents’ houses.

Naming this situation “a society with excessive residential supply,” I define it as a society that continues to build massive houses, overlooking the serious effects on future generations and spreading places of residence in a manner similar to slash-and-burn farming (a farming method that burns forests at harvest-time and repeats cultivation haphazardly), despite the number of houses already in existence and the continuous increase in the number of vacant houses.

The structural problems created by both industry and the public/private sectors provide the context. By excessively relaxing city planning regulations as an economic measure, the state has made it easy to construct housing, and municipalities have continued the excessive relaxation of controls on development as they attempt to increase the population. The housing, construction, and financial industries continue to build residences to secure revenue, but there has been no fundamental shift away from the focus on offloading properties on the buyer. House buyers have bought without carefully considering life in the distant future when they are old and no longer able to drive, or the risk of the house standing vacant after inheritance.

This is how the state, local governments, the industry sector, and the population have focused solely on creating houses without paying attention to closing or inheriting/taking over houses. We are now in a situation where we have to foot the bill all at once. We might well refer to the problem as the aftermath of the period of high economic growth period when housing was continuously built and we were buying houses as if they were replaceable consumer goods such as cars or household appliances.

Whack-a-mole Measures for Vacant Houses

The Vacant Houses Special Measures Act took effect in February 2015. The Act facilitates public measures to deal with vacant houses (specific vacant houses, etc.) that have a negative impact on local safety, sanitation, the living environment, or the scenery. Specifically, municipal departments in charge of vacant houses were allowed to access municipal property tax information in the search for the owners of vacant houses. Many municipalities attempted to identify and contact the owners regarding proper management in cases of reports or complaints of dilapidated vacant houses.

However, municipal vacant house measures are faced with barriers such as finances, manpower, or moral hazard, so they focus on contacting owners of specified vacant houses that are extremely badly dilapidated. This is nothing but an endless game of whack-a-mole because, as time passes, the average vacant house becomes increasingly dilapidated and one house after another turns into a specified vacant house. In reality, a new set of circumstances has arisen where vacant houses, which are not dilapidated or in need of measures, or ordinary vacant houses, which are not targeted by municipalities, become specified vacant houses all at once due to the increasing and intensifying disasters.

The Penalty for Postponing the Problems

Why are vacant houses on the increase? After inheriting the house of parents, it is unavoidable that the house stands vacant for a certain period due to the heirs’ inability to sort out belongings and Buddhist altars, or to take the decision to dispose of a house that holds so many memories, or to resolve quarrels over the inheritance. If houses are sold or rented out in a usable state, no major issues with vacant houses arise, but unfortunately, in Japan, once a house becomes vacant, the problem is often postponed for a long time and the house is abandoned.

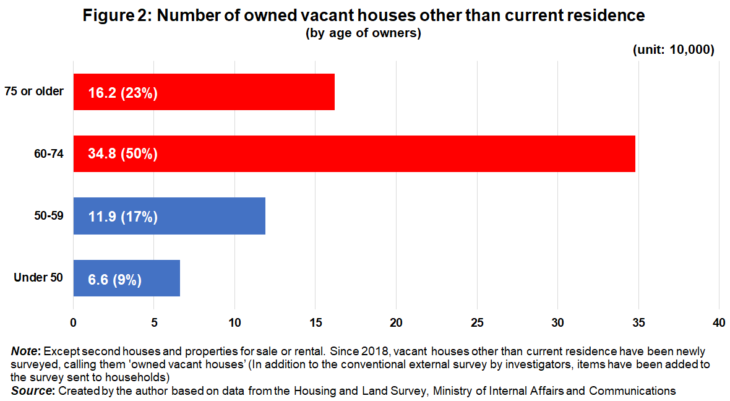

According to the survey of vacant houses owned by households, other than current residences, the Housing and Land Survey (2018), Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, 73% of vacant houses that have been inherited or gifted (excluding second homes, or homes for sale or rent) have been left in a state of neglect for more than five years. Additionally, owners of vacant houses other than current residences are growing increasingly old with 50% in the 60–74 age bracket, and 23% 75 or older. (Fig. 2)

In the future when owners of vacant houses are even older, they will no longer be able to arrange maintenance and management. Even if we try to resolve the vacant houses issue, the physical, mental, and financial burdens will increase, and even when demolition is necessary, the problem will be postponed because it is difficult for elderly owners living off their pensions to raise the funds. When ownership is transferred, property rights to vacant houses are transferred to relatives of the original owners, but heirs continue to abandon their inheritance, resulting in vacant houses with unknown owners. Municipalities are also faced with moral hazard and fiscal difficulties, and without prospects for recovering the cost of demolishing vacant houses, they cannot randomly dismantle houses by subrogation. As a result, a certain number of vacant houses are mothballed imposing the issue on future generations.

Preparation for Closing Houses

This is how the labor, time and cost of resolving the issue of vacant houses increases the more time passes. Consequently, it is essential to prepare for closing houses while the vacant houses are in a usable state and the heirs are still young and healthy.

Preparation for closing a house refers to a series of activities by the owner of the residence or the heirs before the inheritance or, at the latest, by the early stages of a house falling vacant. The activities include studying options for a smooth inheritance or take-over of the residence by responsible owners or users, sharing information, and arranging the prerequisites.

When the Civil Code and the Real Property Registration Act were revised in April 2021, the previously optional registration of transfer of ownership due to inheritance became compulsory. (The change will take effect in 2024.) Some of the details are still unclear, but at the very least, a correctional fine of 100,000 yen or less will be levied for failure to report the transfer without valid reason. As a result, it is expected that an increasing number of people will start preparations for closing houses including finding a reliable advisor, discussing what to do with the house and land (who will inherit/ take over, or sell, rent, demolish etc.), and finding out how to register future inheritance of house and land.

The Grave Issue of House Demolition

However, there are major barriers to house demolitions even if you try to prepare to close a house. For example, many demolitions do not progress because the owners have difficulty raising the necessary funds. Long postponements of the problem after an inheritance and aging owners are also part of the context. If vacant houses are demolished, property taxes increase because the special measures for residential land are canceled, so in some cases vacant houses are abandoned unless the land is likely to sell.

Seeing the situation, more municipalities are subsidizing the demolition costs for old dangerous houses that were built to the old pre-1981 seismic code. A minority of municipalities including Takasaki, Gunma Prefecture, are subsidizing the cost of demolishing not only old dangerous houses, but also vacant houses that risk endangering the surrounding area. However, there are fiscal limits to this system. It cannot be introduced in all municipalities and if taken too far, there is the chance of moral hazard.

Therefore, it is essential to formulate a taxation system that promotes the demolition of vacant houses by providing incentives for individual owners to demolish unserviceable or unused vacant houses at their own expense in the early stages after inheritance. In terms of disaster preparedness, the issue of numerous vacant houses abandoned without demolition after a disaster is becoming increasingly important. In June 2021, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) revised the guidelines for specific vacant houses. The guidelines clearly state that in terms of property taxes, the special measures for residential land do not apply to land occupied by poorly managed vacant houses regardless of whether the house in question is a specified vacant house or not. This trend is already visible in Kawaguchi, Saitama Prefecture, and Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture. However, it is possible that these trends will not materialize unless municipalities have the manpower and financial resources for the work of surveying and determining whether a vacant house is poorly managed.

Lack of Support Measures for Closing Houses

Such measures for poorly managed houses encourage management and demolition by owners from the negative perspective of a rising tax burden. However, to curtail the incidence of vacant houses and to promote demolition of vacant houses in disaster hazard areas, it is also important to enhance positive measures that support demolition, such as introducing incentives for owners to demolish houses at their own expense.

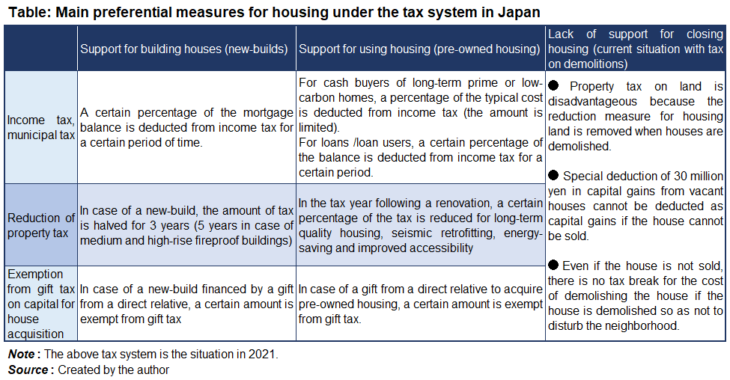

In the past, national housing policies have emphasized measures to support building and using housing, such as municipal property tax relief measures to encourage circulation of new-builds and pre-owned housing, or tax deduction on housing loans. However, unfortunately, there have been literally no measures to support the closing of houses. As a vacant house measure, the state has introduced a special tax deduction of 30 million yen, which applies to capital gains tax on the sale of vacant houses, but the demolition cost can only be subtracted as transfer cost if the vacant house has been sold. At the stage where the vacant house cannot be sold, the cost of demolition is a housekeeping expense in taxation terms, and there are no tax reduction measures. Therefore, some aspects of the tax system make it disadvantageous to close a house. Accordingly, we have now arrived at a stage where we must consider a taxation system that promotes the demolition of vacant houses so that owners (including future heirs), who raise the funds to demolish a house within a certain period after the inheritance, are eligible for tax breaks on the cost of demolition, or inheritance tax breaks on condition of circulating the property through demolition or sales.

Pros and Cons of a Japanese Version of the Land Bank

Meanwhile, when preparing to close houses, it is likely that individuals will encounter issues with land and vacant houses that they cannot address on their own, such as land that is unsuitable for residential use due to the high risk of sediment-related disaster, or several unidentified owners. It is now an urgent issue to consider a public organization like the Federal Land Bank (FLB) to take on these problems.

In the current situation where frequent disasters occur across the nation, we must firmly grasp the opportunity to prepare to close houses built on high-risk land that is unsuitable for residential use from the perspectives of disaster prevention and reducing the impact of natural disasters. An organization like the FLB could “close” land use each time a property is inherited by, for example, receiving donations of land where the risk of disaster is high.

In the long term, such measures will not only protect lives, but they also have the potential to curtail total public investment in disaster responses, so this is an option worthy of consideration. But, if a public body continues to own and manage land that is unusable and expensive to maintain, the tax burden will increase.

We are now at a stage where all citizens need to be ready to share the burden of protecting and managing the whole country to close houses in order to deal with the aftermath of the period of high economic growth and the increasing and intensifying disasters.

Meanwhile, we must also revise the regulations and incentives for building new homes. The current urban planning and housing policies still rely on specifications for the period of high economic growth. We must start serious discussions about how we can restructure this and move from the new-build phase to regulatory policies and incentives that incorporate ways to raise funds to cover the cost of closing.

If we don’t make serious attempts to reverse the situation of the ever-increasing numbers of houses, residential land, and vacant houses as depopulation gains momentum, the present generation will end up imposing the aftermath of a society with excessive residential supply on future generations.

Related article: Vacant Houses are Undermining Tokyo Reconsider the Relaxation of City Planning Regulation Distortions in a “Society with Excessive Residential Supply” Created by the Industry, Government and Private Sector

www.japanpolicyforum.jp/society/pt201709111001346999.html

Translated from “Tokushu ‘Tochi to Ie to Nihonjin:’ Akiya/Shoyusha-fumei tochi mondai no genzai—Sumai no shukatsu wo ikani susumeruka (Land and Homes and the Japanese: The issue of vacant houses and land with unknown owners today—What progress with preparations for closing houses?),” Chuokoron, December 2021, pp. 66-73 (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [January 2022]

Keywords

- Nozawa Chie

- School of Political Science and Economics

- Meiji University

- house ownership

- vacant houses

- house ownership

- disaster areas

- typhoons

- hazard areas

- Vacant Houses Special Measures Act

- excessive residential supply

- closing houses

- house demolition

- inheritance

- property tax

- capital gains tax

- property rights

- Real Property Registration Act

- Housing and Land Survey

- Land Bank