Ancestors and the Japanese People—Graves and Funerals from the Perspective of Modern History

Toishiba Shiho, Research Fellow, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

What were ancient Japanese tombs like?

Toishiba Shiho, Research Fellow

All sorts of funerals have been held in Japan since ancient times, so the traditional Japanese funeral is difficult to define. One great king built a huge “kofun” burial mound. Another emperor wanted his ashes to be scattered. Before dying, Shinran (1173–1263), founder of the Jodo Shinshu sect of Buddhism, said his remains should be thrown into the Kamo River in Kyoto for the fish to eat. But contrary to his dying wish, his remains are still respectfully enshrined in the Otani Mausoleum.

It is thought that aerial sepulture (wind burial) was the norm for the graves and funerals of common people, at least until around the 12th Century. Very few examples of cemeteries for ordinary people have been excavated from Nara and Heian period (8th–12th centuries) archaeological sites, and even those are small, with only a few people buried in them.

From the beginning of the Middle Ages, in some parts of Japan, the custom also arose of building communal cemeteries and erecting memorial towers and stupas with Buddhist significance, as well as depositing bones on sacred mountains such as Mount Hiei and Mount Koya. [Katsuda Itaru, Nihon Soseshi (History of Japanese Funeral System), 2012]

By the early modern period, under a system in which people had to register with a temple, the number of temples with their own cemeteries increased, and middle and upper-class people living in Edo (present-day Tokyo) began to erect magnificent tombstones for their families at their family temples.

The folklorist Yanagita Kunio (1875–1962) wrote in his book Meiji Taisho shi seso-hen (Social Conditions and Lives During the Meiji and Taisho Periods), published 1931, that at one time corpses were returned to the mountains, seashore and other natural places, and that cemeteries were “places normal to eventually forget,” but that by the early modern period, graves had become “sites of permanent memorial.” He also pointed out that this made the existence of graves untended by relatives even more conspicuous.

Meanwhile, even in Edo of the same period, the bodies of lower class workers who lived in nagaya tenement houses were often disposed of by “throwing” them into temples [Haka to maiso to Edo jidai (Tomb, Burial and Edo Period), edited by the Edo Archaeology Research Group, 2004]. And across Japan, funeral customs specific to each region were developing. In some regions gravestones were erected away from where the body was buried, in others all the cremated remains were left on the spot.

In Amami and Okinawa, there was also a custom of washing the bones, which involved ground burial or aerial sepulture, and then taking them out several years later to wash and purify them [Minzoku shojiten: Shi to soso (Encyclopedia of Folklore: Death and Funerals), ed. Shintani Takanori, Sekizawa Mayumi, 2005]. In some regions, these diverse funeral customs continued until after WWII.

But contemporary Japanese people (except in places such as Okinawa) probably imagine something like the same shape when they think of an ordinary grave. A square stone pillar is erected with the inscriptions “The grave of the X family” and “The grave of the ancestors.” The cremated remains of the family are stored in a bone chamber underneath. These tombs are inherited by descendants down generations (referred to as “family graves” below).

The funeral customs of ordinary people have shifted from varying completely depending on region, to the current situation where remains are preserved in family graves, respectfully enshrined and passed down the generations. This change has proceeded in many regions and is now almost standard across the country. Over the years, the shape and meaning of the grave has changed greatly.

Modern Japanese identity

What prompted this uniformity in graves was not a change in how Japanese see life, death or the spirits of the deceased. Rather, it was the concept of “the proper way for Japanese people to worship ancestors and keep graves” conceived alongside the modern Japanese “ideal image of the nation and city” and “ideal image of the people.” In fact, how to interpret ancestor worship was a big problem for Japan as it sought to set up a modern nation-state.

This is because in the nineteenth-century West, “ancestor worship” (many Japanese feel that the word “worship” is an overstatement; it is easier for them to understand if it is expressed as kuyo, meaning “ancestral memorial service”), was considered the superstitious magic of people in primitive societies who feared and worshipped the spiritual power of their ancestors. At that time, the humanities and social sciences employed social Darwinism as a self-evident framework, a theory that has been completely abandoned today. In that context, religious studies, anthropology, and sociology tried to clarify the process of religious evolution, conducted research on the belief systems of indigenous societies in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Oceania, which were considered primitive societies, and found fetishism, animism, manaism, totemism, shamanism, and ancestor worship. They argued that human religion came from these most ancient forms through several stages, eventually evolving into monotheism [Shukyo no tanjo—Shukyo no kigen, kodai no shukyo (Birth of Religion—Origin of Religion / Ancient religion) ed. By Tsukimoto Akio.]

It is an important point, however, that the French historian Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges (1830–1889) and the British sociologist Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) criticized the prevailing view of ancestor worship as something unique to primitive peoples, and argued that it was a transcultural and universal practice that was also practiced in ancient Europe. Even so, there was no change in the perception that ancestor worship belonged to primitive societies and that those who still practiced it were primitive people.

To be labeled as an uncivilized nation that practiced ancestor worship was fatal to the intellectuals of modern Japan, who aspired to be a first-class nation on a level with the West. Yet, there was a Japanese man who boldly insisted to Western intellectuals that our ancestor worship was not uncivilized. This was Hozumi Nobushige (1855–1926), the man who drew up the Meiji Civil Code. As a youth, Hozumi completed studies in law in England and Germany, and as Japan’s first doctor of law, he was a professor at Tokyo Imperial University and Dean of the Faculty of Law. He was also known as the husband of Shibusawa Eiichi’s eldest daughter Utako.

In 1899, Hozumi traveled to Rome to give a lecture in English titled “Ancestor Worship and Japanese Law” on Japanese ancestor worship and the Meiji Civil Code. This lecture was a great opportunity for Japan, which was in the process of revising the unequal treaties, to present itself to the world as a modern nation that had successfully compiled a Civil Code before Germany. It was a very important national mission.

Quoting a number of theories from Western academia, including de Courange’s book La Cité Antique, Hozumi began by saying that ancestor worship is a transcultural practice that used to be practiced in the West, but is now in decline. He also argued that it is precisely because Japan was not invaded and ruled by other countries, has an unbroken imperial line, and has preserved the inherent character of its people, that it has been able to maintain the custom of ancestor worship to the present day. He argued that this was extremely useful for social integration, and hence Japan had succeeded in becoming the first modern Asian nation.

Two years later, the lecture was published in book form in English and German. It was widely read in Western academic circles as essential to understanding Japan’s unique society and culture.

Ancestor worship that became tradition

This identity of “a people who enshrine their ancestors” projected out to Western countries was then turned inwards and propagated within Japan.

After the Russo-Japanese War, against a backdrop of worsening finances and exhausted farming communities, social movements became more active, and the rise of Western imported ideas such as utilitarianism and individualism, as well as socialism and naturalism, which were seen as unhealthy and dangerous, was considered a problem. Meanwhile, it was a time of public calls regarding the importance of widespread education in the unique national morality of the Japanese race. University professors and intellectuals once again thought on the question, “What kind of country is Japan?” They found Japanese specialness and uniqueness in the emperor system with its unbroken lineage, the loyalty and filial piety of the people, Japan’s history, the fact that Japan is a heavily-forested island nation with four seasons, the culture of rice cultivation, and the spirituality of Shintoism, Bushido, the family system and ancestor worship. Then they advocated a national morality that brought together all these elements, and positioned ancestor worship as an important foundation. Thus, from the latter half of the Meiji period, ancestor worship and visiting family graves were encouraged as part of school education. For example, in 1910, the Ministry of Education published a government-designated textbook called Koto shogaku shushinsho—Shinsei dai-san gakunen yo (Higher Elementary School Moral Training Book for the Third Grade of the New System), which included a chapter on “ancestors.”

It stated that it is the “beautiful custom of our country to respect the family line and worship our ancestors.” Ancestor worship was based on national customs and natural emotions, and should be treated with importance no matter what religion a person believes in. It also said that the regular events of the annual rituals are “vitally important customs” that cultivate respect for ancestors and filial piety.

If students asked, “Why must we worship our ancestors?” there was no way that any educator could say that it was to pray for the souls of their ancestors, to pray for blessings, or that they’d be cursed by their ancestors if they didn’t make offerings to them. Ancestral worship was probably considered appropriate for a civilized country because it was a beautiful custom and Japanese custom, because it was an important custom, and because it fostered filial devotion to one’s parents and ancestors.

Creating graves appropriate for a civilized nation

As an awareness of ancestor worship as a good tradition and national custom took root among people, next a question arose: “Then, why are graveyards still so run down?” At that time, the cemeteries of urban temples, which could easily be seen by foreigners, were densely packed with gravestones and overgrown with weeds, just like the scenes drawn by Mizuki Shigeru in his manga Hakaba Kitaro (known as GeGeGe no Kitaro in its animation version).

What’s more, as recorded by Yanagita Kunio, the number of untended graves had conspicuously increased during the violent economic ups and downs of the early Showa period. On the other hand, some wealthy people proudly erected tombs so big that people had to gaze up at them, while graves of somewhat eccentric and strange design also appeared.

Moreover, as I mention above, diverse funeral customs remained across Japan. From the government’s perspective, there was no control over this, as would have been appropriate for a modern nation, and bad customs remained. So arose the idea of creating a cemetery scene suitable for Japan, a country of the first rank, equal to the West and with a tradition of ancestor worship. Inoshita Kiyoshi (1884–1973), an engineer (later, section manager) in the Tokyo City Parks Department, produced a design for a cemetery modeled after a German cemetery; one that was rich in nature and where people could enjoy walking. Based on this design, Japan’s first park cemetery, Tama Graveyard (later renamed Tama Cemetery) was established in the suburbs of Tokyo in April 1923. At that time, however, the Tamagawa Cemetery was in a wild and undeveloped area, and access to the cemetery was inadequate, so hardly any graves were sold. On top of that, six months later in September, the Great Kanto Earthquake struck.

From Tokyo to Yokohama, many graves in existing cemeteries collapsed. So, Inoshita took the lead in devising the family grave that Japanese people today are all familiar with. These new graves would be hygienic, dignified and pleasing to the eye, use little space, and have an improved lower structure so that they would not be shaken by a small earthquake. Family graves were installed one after another in renovated graveyards and new cemeteries as part of the earthquake reconstruction projects.

Obon as a time for visiting graveyards with family

In Tokyo and Osaka, family graves were already becoming common before the war, but they quickly became popular in most other city areas when large-scale cemetery reorganization was carried out as part of postwar reconstruction projects. It took more time for them to spread to all corners of Japan.

In the 1980s, as the shortage of cemeteries got worse, developers built large cemeteries in the suburbs, attracting customers with advertisements and through contact points such as department stores. A battle for sales developed, with loans now available to those purchasing graves. The graves were mass-produced in the style of ready-built houses, installed according to identical plans, then finished by carving “X family” on the gravestone. As people’s standard of living improved, it became possible to purchase a grave costing several hundred thousand to several million yen. What’s more, the spread of family graves was also enabled by motorization that gave people the ability to visit a cemetery far away during time off. It became standard for newspapers to run articles about traffic jams of people visiting graves during the Buddhist festivals of Bon and Higan. Demand was also boosted by TV news and commercials showing images of children with their hands in prayer at graves.

|

|

|

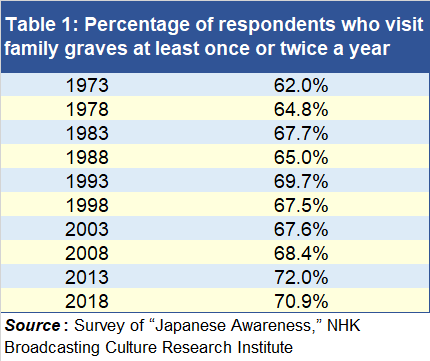

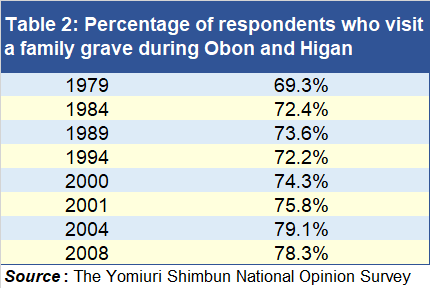

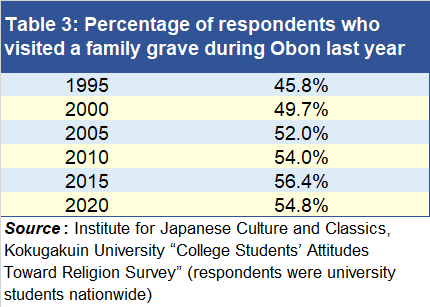

These days, along with visiting a shrine at New Year, visiting a family grave is one of the religious rituals most familiar to Japanese people. The survey results in tables 1 to 3 show that even today most Japanese, including younger generations, still have the custom of visiting family graves. Moreover, the percentage has not declined over the past few decades, and may even be said to be trending upward slightly. At one time, Japanese scholars of religion predicted that people’s faith, religious practices, and awareness of the need to continue their family heritage over generations would fade with the times, and that memorial services for ancestors would decline. It seems, however, that their reading was off, at least when it comes to visiting family graves.

Why hasn’t visiting family graves declined? In a questionnaire survey conducted with permission from a cemetery in Kobe City, I asked 103 cemetery users, “What does a family grave mean to you?” allowing people to add any comments they wish. The most common responses were “a place of spiritual comfort and support” (12 respondents), while the answers “a place to rest in peace,” “something to cherish and pass on,” “gratitude to ancestors,” “remembering and holding memorial services for the deceased,” “feeling connection with ancestors and life,” and “confirming family ties” were given by more than five more respondents each.

On the other hand, some respondents said that family graves have no meaning, that visiting graves is no more than a custom, and that looking after them is a problem.

While, in a broad sense, there is certainly a religious desire to hold memorials for ancestors and the deceased, to talk to them, to be watched over by them, and to have them rest in peace, actual graves are difficult to look after, and that is the reality of graves in Japan today.

Graves and the future of mourning

When we consider the modern history of graves, as explained above, we see that the current form of the family grave was not created according to Japanese people’s views on life and death or their religious beliefs; rather, it was mostly determined by separate systematic and physical constraints. And later, the form of the family grave may have, in effect, influenced people’s views and behavior.

For example, when a family grave is built in Japan, it provides a strong sense of family and the desire to continue on the generations, and it motivates family to often visit the tomb to look after and honor it. Mossy, weed covered, toppling and collapsing graves really do give the impression that the deceased are not resting in peace. The cost of keeping family graves in good condition to prevent this situation could be a burden for many Japanese people.

Graves are a specialty product with an extremely long lifetime of use. Even when a product that solves an existing issue is introduced, it takes quite a long time for it to completely replace the old product and for any weaknesses then to become apparent. In the case of family graves too, it was not until about 50 years after their appearance that a critical problem came to light; namely, the high cost of maintenance, and the fact that if there is no one to inherit a grave, it will become untended.

Even back in the 1980s, a problem had already arisen of single people and couples without children being refused contracts for graves by any cemetery or temple. During the 1990s, people became increasingly worried about putting a burden on their children and critical of the environmental impact of clear-cutting mountain forests to build cemeteries and using large quantities of stone. This led to new kinds of graves appearing, such as “perpetual memorial services,” shared graves, natural burials and tree burials.

Today, fewer people are getting married and the birthrate decline is accelerating. This would probably have been unimaginable in the days when families just kept on expanding, but today one in four men aged 45–54 has never married and is very likely to stay single for the rest of his life [Mikon chunen hitori bochi shakai (Solitary Society of Unmarried Middle-Aged People), Nose Keisuke and Ogura Toshihiko.] The simple fact is that the number of unmarked graves will increase to match.

At the same time, I also worry whether the current fashion for tree burials, ossuaries in urban buildings, and shared graves is the best solution. Just like with family graves, a few decades from now unexpected problems may arise. They could become a cause of worry for the younger generations of today. How should we mourn our dead? This is an eternal issue for both the living and society.

Translated from “Shukyo no ibasho, shisei-kan no yukue: Gosenzosama to Nihonjin—Kingendaishi kara mita haka to tomurai (The Position of Religion and the Future of How Japanese See Life and Death: Ancestors and the Japanese People—Graves and Funerals from the Perspective of Modern History),” Chuo koron, February 2022, pp. 123–129. (Courtesy of Chuokoron Shinsha) [March 2022]

Keywords

- Toishiba Shiho

- Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

- ancestors

- ancestor worship

- religion

- funerals

- funeral customs

- mourning

- graves

- gravestones

- burial

- cemeteries

- Hozumi Nobushige

- national identity

- Obon

- Higan