Beyond the COVID-19 Crisis: How “national isolation” in human resources prevents more quality

Kariya Takehiko, Professor, Oxford University

Key points

- Despite higher levels of education, labor productivity is not rising.

- The closed nature of the human capital market is also affecting non-regular employees.

- We must increase diversity of human resources, not rest on our laurels here in Japan.

Prof. Kariya Takehiko

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries temporarily closed their borders, putting a brake on the free movement of human resources. Bearing in mind the small number of infected people, by refusing entry to foreign students for an extended period, Japan’s response is like its historic “national isolation.” Amid competition for human resources in the global arena, will post-COVID-19 Japan be able to make its human resources more skilled and diverse?

The famous French thinker Michel Foucault made a fascinating point in a lecture in his later years. It was that the market, which had long been a place of exchange, had turned into a place of competition as neoliberal thought conquered the world. From this, we can draw out the topic of how to understand the relationship between exchange and competition in the market, and in Japan’s case especially, the human capital market.

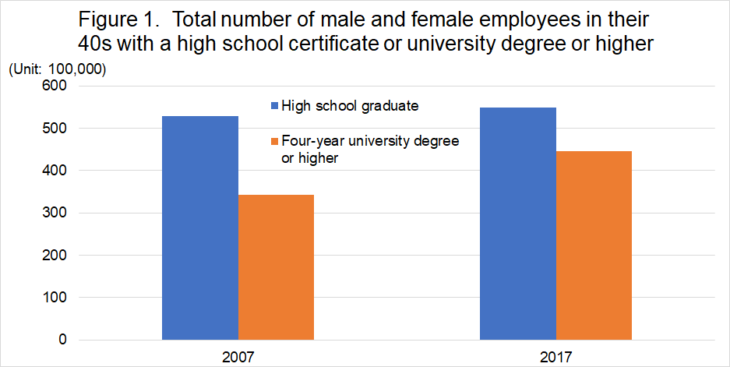

Between 2007 and 2017, the number of employed men and women in their 40s, i.e. those considered the mainstay of the working-age population, with a college degree or higher increased by about one million (see Figure 1). According to the kind of knowledge about economics you’d find in a textbook, more educated workers should lead to an increase in human capital, indicating potential for higher labor productivity in society as a whole. On the other hand, from an international perspective Japan’s labor productivity and real wages are conspicuously stagnant.

In light of this fact, something mysterious comes to the fore. The labor market is a place of exchange. So, if the value of human capital increases as a result of higher levels of education, that should lead to higher labor productivity and, correspondingly, higher wages. In other advanced nations, the working-age population has become more educated, and labor productivity has increased in parallel. But in Japan this phenomenon didn’t occur. Why is that?

One answer is the expansion of non-regular employment. Non-regular employment does not make full use of human capital’s value (i.e. knowledge and ability) and is limited to low productivity. The theory is that, for this reason, it doesn’t lead to increased labor productivity.

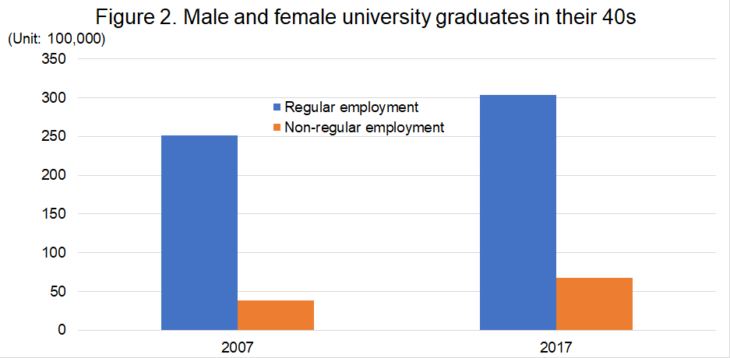

And this theory is partly true. Between 2007 and 2017, among employed university graduates (graduates of four-year university courses only here), the number of non-regular employees increased by about 300,000 but the number of regular employees also increased by more than 500,000 (see Figure 2). In short, there has been a great increase in the stock of highly-educated human capital even among those who do regular jobs.

One could theorize that the quality of education in Japan is low, but this is not correct. The 2011–12 Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), which was conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), showed that Japanese adults ranked first in both numeracy and literacy, with little variation in score. When it comes to the fundamental intellectual abilities of adults, the study confirmed that the human capital of Japanese society is high level. One can call this the result of education and training.

The key to solving this mystery lies with exchange and competition in Japan’s human capital market.

First, let’s think about a situation where the market is open to the world. In the university admissions market, there is global competition for the highest quality students. Competition occurs among universities to provide costly quality education, provide a well-endowed research and teaching environment, and over tuition fees. And the more competitive universities are in this market, the more able they are to attract high-quality students, even when charging relatively high tuition fees. As a result, they can invite high-quality teaching staff at high wages, giving them an advantage when recruiting students and during external fundraising. This phenomenon is a virtuous circle that enhances the quality of universities in the English-speaking world.

Even in the labor market for new graduates, job seekers compete across national borders for jobs matching their abilities. Employers, meanwhile, compete to attract high-quality human resources with wages, benefits, and especially by providing opportunities for employees to demonstrate and utilize their abilities. If competition for quality arises on both sides, the productivity of companies will increase and generate profit to match the increase in labor productivity of employers. And that will be reflected in employee benefits.

Many of these global companies do not stick to internal promotion; instead, they attract quality external talent and provide commensurate wages and benefits. This is happening across the world in the market for human capital.

In the context of this open market model as an ideal type, the exact nature of Japan’s human capital market becomes clear. Japan’s human capital market, walled in and protected by borders, language, and Japanese customs, has been closed to the world. Entrants to the university entrance market and the graduate job market are almost all Japanese. No matter how fierce competition during exams for the university enrollment market, what is exchanged for success in entrance examinations is not limited to quality education, but includes “symbolic” goods such as prestige and status of the university.

These symbolic goods give advantages in the post-graduation job market. But the job-seeker market, where starting salaries do not differ much, is a place of competition and exchange for future stability and the right to compete for promotion (i.e., competition for status) after joining the company.

Exchange and competition in these markets does not result in the creation of a cycle in which the value of human capital increases. Firstly, access to this market is closed, and secondly (a byproduct of this), the things exchanged in the market are symbolic goods such as the “status” of universities and companies. Some economic rewards come too, but the differences are not large, except in the case of non-regular employment where economic rewards are strictly limited and far behind those for “regular” workers.

In the internal (in-company) labor market, after winning the graduate job market and becoming a “permanent” employee, the object of exchange and competition is the chance to be promoted to higher status. Over the years opportunities to demonstrate competence come along too, and the employee needs to align with the organization. No-one enters from outside to threaten competition or cause large differences in remuneration.

The three markets mentioned so far are all strongly influenced by age-based considerations, and individuals compete against others who joined the company at the same time as them. If we apply the reference group theory from sociology, this means that the object of comparison is a group of the same age that has managed to enter a closed market.

The result is selection that increases homogeneity, but in such a market, “heterogeneity” is eliminated and “difference” solely within the homogeneous group is seen as a great matter. What’s more, unlike in markets where price competition arises over tuition and scholarships, or wages and remuneration, the exchange rate in this market is determined by the relative position of individuals in the reference group, and the main compensation is feelings of satisfaction and superiority.

On top of this, such symbolic goods are relatively categorized values determined by whether the individual is part of a set recruitment quota (university enrollment or company recruitment capacity), and don’t have a quantified value that can be continuously indicated like money.

Japanese people are used to this system and take it for granted, but it is unlikely to work and be understandable for high-level human resources from overseas. And because of this, the market becomes still yet more closed and homogenous.

The result is that a quality-enhancing cycle, as in the open market model, is unlikely to develop. Nor does it tend toward competition to increase or acquire absolute quantified value, such as wages and opportunities to demonstrate ability—exchanged values in the market that correlate to the “quality” of human capital. The only way for individuals to get there is to take more risk and spin out from the mainstream.

I don’t think that Japanese-style neoliberalist reformers, who emphasize competition left up to the market (i.e., market principles), understands these characteristics. The result is that it preserves these characteristics, while creating and widening a gap with non-regular workers who are excluded from the mainstream human capital market.

The only way to escape this cycle is to rethink the system of exchange and competition. It’s not a good idea for Japan to suddenly aim for a global human resources market in which it would be disadvantaged. The only way to change the current system and clearly differentiate it from neoliberalism is to try and diversify the human capital market by increasing heterogeneity, including gender, age, and nationality. This cannot be done while Japan is obsessed with a sense of “isolation” that doesn’t like heterogeneity and prioritizes domestic peace of mind and stability for a minority. That is the challenge for post-COVID Japan.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 6 January 2022 under the title, “Korona-kiki wo koete (III): Jinzai no ‘sakoku,’ shitsu kojo wo sogai (Beyond the COVID-19 Crisis (III): How “national isolation” in human resources prevents more quality).” The Nikkei, 6 January 2022. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Kariya Takehiko

- Oxford University

- human capital

- human resources

- quality of human capital

- education

- literacy

- numeracy

- labor productivity

- labor market

- homogenous

- borders

- language

- neo-liberalism

- market principles

- heterogeneity

- exchange

- competition

- COVID-19

- national isolation